Lamb shift

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

Feynman diagram |

| History |

|

Background

|

|

|

Incomplete theories |

|

Scientists

|

In physics, the Lamb shift, named after Willis Lamb (1913–2008), is a small difference in energy between two energy levels 2S1/2 and 2P1/2 (in term symbol notation) of the hydrogen atom in quantum electrodynamics (QED). According to the Dirac equation, the 2S1/2 and 2P1/2 orbitals should have the same energies. However, the interaction between the electron and the vacuum (which is not accounted for by the Dirac equation) causes a tiny energy shift which is different for states 2S1/2 and 2P1/2. Lamb and Robert Retherford measured this shift in 1947,[1] and this measurement provided the stimulus for renormalization theory to handle the divergences. It was the harbinger of modern quantum electrodynamics developed by Julian Schwinger, Richard Feynman, Ernst Stueckelberg and Shinichiro Tomonaga. Lamb won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1955 for his discoveries related to the Lamb shift.

Derivation

This heuristic derivation of the electrodynamic level shift following Welton is from Quantum Optics.[2]

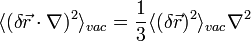

The fluctuation in the electric and magnetic fields associated with the QED vacuum perturbs the Coulomb potential due to the atomic nucleus. This perturbation causes a fluctuation in the position of the electron, which explains the energy shift. The difference of potential energy is given by

Since the fluctuations are isotropic,

.

.

So we can obtain

.

.

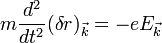

The classical equation of motion for the electron displacement (δr)k→ induced by a single mode of the field of wave vector k→ and frequency ν is

,

,

and this is valid only when the frequency ν is greater than ν0 in the Bohr orbit, ν > πc/a0.

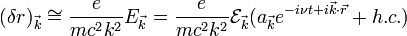

For the field oscillating at ν,

,

,

therefore

.

.

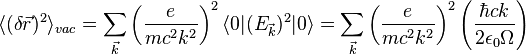

By the summation over all  ,

,

,

,

where  is some large normalization volume (the volume of the hypothetical "box" containing the hydrogen atom) and

is some large normalization volume (the volume of the hypothetical "box" containing the hydrogen atom) and

.

.

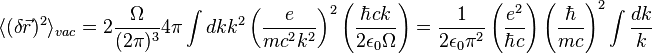

The summation is changed into an integral because of the continuity of k→,  , so that

, so that

.

.

This result diverges when there is no limit about the integral. But this method is valid only when ν > πc/a0, or equivalently k > π/a0. It is also valid only for wavelengths longer than the Compton wavelength, or equivalently k < mc/ħ. Therefore we can choose the upper and lower limit of the integral and these limits make the result converge.

.

.

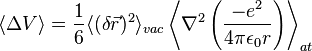

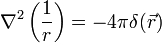

For the atomic orbital and the Coulomb potential,

,

,

since we know that

.

.

For p orbitals, the nonrelativistic wave function vanishes at the origin, so there is no energy shift. But for s orbitals there is some finite value at the origin,

,

,

where the Bohr radius is

.

.

Therefore

.

.

Finally, the difference of the potential energy becomes

.

.

This shift is about 1 GHz, very similar with the observed energy shift.

Experimental work

In 1947 Willis Lamb and Robert Retherford carried out an experiment using microwave techniques to stimulate radio-frequency transitions between 2S1/2 and 2P1/2 levels of hydrogen.[3] By using lower frequencies than for optical transitions the Doppler broadening could be neglected (Doppler broadening is proportional to the frequency). The energy difference Lamb and Retherford found was a rise of about 1000 MHz of the 2S1/2 level above the 2P1/2 level.

This particular difference is a one-loop effect of quantum electrodynamics, and can be interpreted as the influence of virtual photons that have been emitted and re-absorbed by the atom. In quantum electrodynamics the electromagnetic field is quantized and, like the harmonic oscillator in quantum mechanics, its lowest state is not zero. Thus, there exist small zero-point oscillations that cause the electron to execute rapid oscillatory motions. The electron is "smeared out" and the radius is changed from r to r + δr.

The Coulomb potential is therefore perturbed by a small amount and the degeneracy of the two energy levels is removed. The new potential can be approximated (using atomic units) as follows:

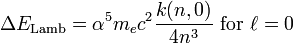

The Lamb shift itself is given by

with k(n, 0) around 13 varying slightly with n, and

with k(n,ℓ) a small number (< 0.05).

For a derivation of ΔELamb see for example:[4]

Lamb shift in the hydrogen spectrum

In 1947, Hans Bethe was the first to explain the Lamb shift in the hydrogen spectrum, and he thus laid the foundation for the modern development of quantum electrodynamics. The Lamb shift currently provides a measurement of the fine-structure constant α to better than one part in a million, allowing a precision test of quantum electrodynamics.

A different perspective relates Zitterbewegung to the Lamb shift.[5]

See also

- Shelter Island Conference

- Zeeman effect used to measure the Lamb shift.

References

- ↑ G Aruldhas (2009). "§15.15 Lamb Shift". Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall of India Pvt. Ltd. p. 404. ISBN 81-203-3635-6.

- ↑ Marlan Orvil Scully & Muhammad Suhail Zubairy (1997). Quantum optics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 0-521-43595-1.

- ↑ Lamb, Willis E.; Retherford, Robert C. (1947). "Fine Structure of the Hydrogen Atom by a Microwave Method". Physical Review 72 (3): 241–243. Bibcode:1947PhRv...72..241L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.72.241.

- ↑ Bethe, H.A.& Salpeter, E.E. (1957). Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two-Electron Atoms. Springer. p. 103.

- ↑ Henning Genz (2002). Nothingness: the science of empty space. Reading MA: Oxford: Perseus. p. 245 ff. ISBN 0-7382-0610-5.

Further reading

- Boris M Smirnov (2003). Physics of atoms and ions. New York: Springer. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0-387-95550-X.

- Marlan Orvil Scully & Muhammad Suhail Zubairy (1997). Quantum optics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 0-521-43595-1.

External links

- Hans Bethe talking about Lamb-shift calculations on Web of Stories

- Nobel Prize biography of Willis Lamb

- Nobel lecture of Willis Lamb: Fine Structure of the Hydrogen Atom

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\Delta E_{{\mathrm {Lamb}}}=\alpha ^{5}m_{e}c^{2}{\frac {1}{4n^{3}}}\left[k(n,\ell )\pm {\frac {1}{\pi (j+{\frac {1}{2}})(\ell +{\frac {1}{2}})}}\right]\ {\mathrm {for}}\ \ell \neq 0\ {\mathrm {and}}\ j=\ell \pm {\frac {1}{2}},](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/c/2/a/cc2ac75040018653e489e68cc3c0665a.png)