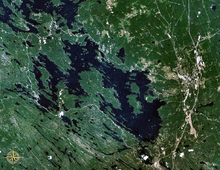

Lake Muskoka

| Lake Muskoka | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Ontario |

| Coordinates | 45°02′N 79°27′W / 45.033°N 79.450°WCoordinates: 45°02′N 79°27′W / 45.033°N 79.450°W |

| Primary inflows | Muskoka River, Indian River |

| Primary outflows | Moon River |

| Basin countries | Canada |

| Surface area | 120 km2 |

| Settlements | Muskoka Lakes, Gravenhurst, Bala |

Lake Muskoka is located between Port Carling and Gravenhurst, Ontario, Canada. The lake is surrounded by many cottages. The lake is primarily in the Township of Muskoka Lakes, with the southeast corner in the Town of Gravenhurst. The Town of Bala, Ontario is located on the southwest shores of the lake, where the Moon River starts. Lake Muskoka is connected to Lake Rosseau through the Indian River and lock system at Port Carling. The lake is mainly fed by the Muskoka River, Lake Joseph and Lake Rosseau.

History

Native people

First mention of Muskoka in any records is in 1615 and the territory was occupied by Indians, mainly consisting of the Algonquin and Huron tribes. Early explorers to the region like Samuel De Champlain came to the area next followed by Missionaries. The name Muskoka is thought to come from the name of a Chippewa tribe chief named Mesqua Ukee which means "not easily turned back in the day of battle".[citation needed] Also known as Chief Yellowhead, it was Mesqua Ukee who signed the treaties made between the Indians and Province of Canada which sold about 250,000 acres (1,010 km2) of land in the area to the Province. He was so revered by the Ontario government that they built a home for him in Orillia where he lived until his death at age 95.

Geography drove history in the Muskoka region. Studded with lakes and abundant with rocks the land offered an abundance of fishing, hunting, and trapping, but was poorly suited to farming. Largely the land of the Ojibwa people, European inhabitants ignored it while settling the more promising area south of the Severn River. The Ojibwa leader associated with the area was Mesqua Ukie for whom the land was probably named. The tribe lived south of the region, near present day Orillia and used Muskoka as their hunting grounds. Another Ojibwa tribe lived in the area of Port Carling which was called Obajewanung. The tribe moved to Parry Sound around 1866.

European arrival

Largely unsettled until the late 1760s the European presence in the region was largely limited to seasonal fur trapping, but no significant trading settlements were established. Canadian government interest increased following the American Revolution when, fearing invasion from its new neighbor to the south the government began exploring the region in hopes of finding travel lanes between Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay[1] In 1826 Lieutenant Henry Briscoe became the first white man known to have crossed the middle of Muskoka. David Thompson drew the first maps of the area in 1837, camped at the present-day Bala during the evening of August 13/14, 1837, and later possibly camped near present day Beaumaris.

Canada experienced heavy European immigration in the mid-19th century, especially from Ireland which experienced famine in the 1840s. As the land south of the Severn was settled, the government planned to open the Muskoka region further north to settlement. Logging licenses were issued in 1866 which opened Monck Township to logging. The lumber industry expanded rapidly denuding huge tracts of the area, but also prompting the development of road and water transportation. The railroad pushed north to support the industry, reaching Gravenhurst in 1875 and Bracebridge in 1885. Road transportation took the form of the Muskoka Colonization Road, begun in 1858 and reaching Bracebridge in 1861. The road was roughly hewn from the woods and was of corduroy construction, meaning logs were placed perpendicular to the route of travel to keep carriages from sinking in the mud and swamps. Needless to say this made for extremely rugged travel. The lumbering industry spawned a number of ancillary developments, including as mentioned, transport, but also settlements began springing up to supply the workers and Bracebridge, (formerly North Falls) saw some leather tanning businesses develop. Tanners used the bark from lumber to tan hides thereby using what otherwise would be a waste product.

The passages of the Free Grants and Homestead Act of 1868 brought opened the era of widespread settlement to Muskoka. Settlers could receive free land if they agreed to clear the land, have at least 15 acres (61,000 m2) under cultivation, and build a 16 by 20-foot (6.1 m) house. Settlers under the Homestead Act, however, found the going hard. Clearing 15 acres (61,000 m2) of dense forest is a huge task, but once the land was clear they were greeted with Muskoka's ubiquitous rocks, which themselves had to be cleared. The soil in the region turned out to be poorly suited to farming consisting largely of a dense clay. As news of the difficult conditions spread back to the south it looked as though development in Muskoka might falter but for a fortuitous development. In a time when the railroads had not yet arrived and road travel was notoriously unreliably and uncomfortable, the transportation king was the steamship. Once a land connection was made to the southern part of the lake in Gravenhurst the logging companies could harvest trees along the entire lakefront with relative ease, so long as they had the means of powering the harvest back to the sawmills in Gravenhurst.

The steamship era

Alexander Cockburn answered the call. Sometimes called the Father of Muskoka,[2] Cockburn began placing steamers on the lake.[3] Starting with the Wenonah, Ojibwa for first daughter, in 1866 Cockburn pressed the government to open the entire Muskoka lake system to navigation by installing locks in Port Carling and opening a cut between Lake Rosseau and Lake Joseph at Port Sanfield. The government responded to the call, eager to reinforce development in light of the faltering agricultural plan, and built the big locks in Port Carling in 1871. Now Cockburn's steamers had access to the entire lake system. Through the years he added more ships and when he died in 1905 his Muskoka Navigation Company was the largest of its kind in Canada.[2]

Shortly after the arrival of the steamships the seeds were planted which would grow in the rocky soil as agriculture never would. In 1860 two young men, John Campbell and James Bain Jr made a journey that marked them as perhaps the first tourists in the region.[4] Taking the Northern Railway to lake Simcoe, they took the steamer Emily May up the lake to Orillia, rowed across Lake Couchiching they walked up the Colonization Road to Gravenhurst where they vacationed. They liked what they saw and repeated the journey every year bringing friends and relatives. These early tourist pioneers increased demand for transport services in the region, drawn by excellent fishing, natural beauty, and an air completely free of ragweed providing relief for hay fever sufferers. Early tourists built camps, but were joined by others desiring better accommodations. Farmers who were barely scratching a living from the rocky soil soon found demand for overnight accommodations literally arriving on their doorsteps. Some made the switch quickly and converted to boarding houses and hotels. The first wilderness hotel was built at the head of Lake Rosseau in 1870, called Rosseau House. It was owned by New Yorker W.H. Pratt. The idea caught on and tourists came establishing the tourist industry as the up-and-coming money earner in the 1880s.

The steamship era gave rise to the area's great hotels; Rosseau, Royal Muskoka, Windemere, and Beaumaris. When the railroad reached Gravenhurst in 1875 the area grew rapidly. Travel from Toronto, Pittsburgh, and New York became less a matter of endurance than expenditure. Trains regularly made the run from Toronto to Gravenhurst where travelers and their luggage were transferred to the great steamers of the Muskoka Navigation Co such as the Sagamo. Making regular stops up the lakes, including Bracebridge, Beaumaris, and Port Carling, tourists there could transfer to smaller ships such as the Islander which could reach into smaller ports. The hotels became the centers of vacationers lives which could stretch for weeks or even months in the summer. As families became seasonally established they began building cottages near the hotels; at first simple affairs replicating the rustic environment of the early camps, but later grander including in some cases housing for significant staff. Initially cottagers relied on rowboats and canoes for daily transport and would sometimes row substantial distances. Eventually the era of the steam and gasoline launch came and people relied less on muscle power and more on motors. With the boats came the boathouses, often elaborate structures in their own right mimicking in many cases the look and feel of the main cottage.

The coming of the car

World War I caused a significant dip in the tourist activity for the area and hence the economy. After the war, however, significant advances in the automobile brought demand for improved (paved) roads. These two developments, motorboats and private cars brought greater overall development of the area and spread development out over the lakes. Freed from the ports of call of the steamships, people built cottages farther afield. Demand began dropping for the steamship lines. World War II caused another decline as wartime shortages kept many Americans at home and many Canadians were engaged in war activities. Postwar prosperity brought another boom based around the automobile and the newly affordable fiberglas boat. Suddenly owning a summer cottage became possible not only for the adventurous or the wealthy, but for many in the middle class. The steamship companies retired their boats one by one until the last sailing in the late 1950s.

Aircraft crashes

During World War II a crash into Lake Muskoka occurred involving a Northrop Nomad A-17A, which still contains the remains of British pilot, Peter Campbell, and Canadian pilot, Ted Bates. The pair collided with another Nomad over southern Lake Muskoka and crashed into the lake's icy depths on December 13th, 1940 while searching for another pilot that had gone missing in a snow storm the day before. The other plane they crashed into also plunged into the lake; however, it and its two dead crew members were brought to the surface in 1941, leaving Campbell and Bates behind on the lake's 140 foot bottom.

Between 1942 and 1945, at the Muskoka Airport, the Royal Norwegian Air Force (RNAF) trained Norwegian pilots during World War II at what was then called "Little Norway". One of the planes from a training mission crashed off of Norway Point, killing the pilot. The aircraft was accidentally recovered by a cable crew snagging the plane in 1960 and the pilot was found inside. For reasons unknown the plane was cut free and fell back to the bottom with the pilot still inside. Authorities are investigating this site as time allows. The RNAF's first fatal accident in Muskoka, and the last one recorded by the FTL in Canada, took place August 1944 when a Fairchild PT-19 Cornell trainer with pilot and student aboard lost its wing and crashed into the ground, south of Gravenhurst; both on board died. The bodies were recovered from the dense undergrowth and a wing section was found, but no wreckage was recovered. Not long after, another Fairchild crashed for the same reason, but both occupants escaped by parachute.

Lake Front Resident Advocacy Group

There are many community groups based on Lake Muskoka. The largest of these is the Muskoka Lakes Association (MLA). The MLA was founded in 1894 to represent the interests of lakeshore residents on Lakes Rosseau, Joseph and Muskoka and many smaller surrounding lakes.

Famous cottagers

- Eddie and Alex Van Halen

- Mike Weir

- Nancy Dolman

- Steven Spielberg

- Tom Hanks

- Kevin O'Leary

- Derek Roy

- Edward Norton

References

- ↑ Ahlbrandt p 16

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ahlbrandt p 21

- ↑ "Alexander Peter Cockburn". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Archived from the original on 2009-09-25.

- ↑ Ahlbrandt p35

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Muskoka. |