Laetoli

Laetoli is a site in Tanzania, dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its hominin footprints, preserved in volcanic ash (Site G). The site of the Laetoli footprints is located 45 km south of Olduvai gorge. The location was excavated by archaeologist Mary Leakey in 1978. “The Laetoli Footprints” received significant recognition by the public, providing convincing evidence of bipedalism in Pliocene hominids based on analysis of the impressions.

Dated to 3.6 million years ago they were also the oldest known evidence of bipedalism at the time they were found, although now older evidence has been found such as the Ardipithecus ramidus fossils. The footprints and skeletal structure excavated at Laetoli showed clear evidence that bipedalism preceded enlarged brains in hominids. Although it is highly debated, it is believed the three individuals who made these footprints belonged to the species Australopithecus afarensis. Along with footprints were other discoveries including hominin and animal skeletal remains and Acheulean artifacts.

Background

History of research

Laetoli was first recognized by western science in 1935 through a man named Sanimu, who convinced archeologist Louis Leakey to investigate the area. Several mammalian fossils were collected along with a left lower canine tooth, originally identified as that of a non-human primate but later revealed as the site's first fossil hominin in 1979 by P. Andrews and T. White.

In 1938 and 1939, German archaeologist Ludwig Kohl-Larsen studied the site extensively. Several hominid remains, including premolars, molars, and incisors, were identified within the German collections. A later excavation in 1959 revealed no new hominids, and the site went relatively unexplored until 1974—when the discovery of a hominid premolar by George Dove renewed interest in Laetoli. Mary Leakey returned to the site and almost immediately discovered the well-preserved remains of hominids. In 1978, Leakey's discovery of hominid tracks—“The Laetoli Footprints”—gained significant recognition by both scientists and laymen, providing convincing evidence of bipedalism in Pliocene hominids.

Occupational history

Although much debated upon, it has been determined that Australopithecus afarensis is the species of the three hominins who made the footprints at Laetoli. This conclusion is based on the reconstruction of the foot skeleton of a female A. afrarensis hominin by anthropologists Tim White and Gen Suwa of the University of California, as well as detailed footprint analysis by Russel Tuttle of The University of Chicago, whose experiments included the comparison of both human and bi-pedal animals such as bears and primates, gaits, and foot structure, taking into account the use of footwear. For gait, Tuttle looked at the step length, stride length, stride width and foot angle to determine A. afarensis was more human-like in gait than ape-like.

A. afarensis is an obligate bi-pedal hominid with the beginnings of sexual dimorphism attributed to its species, although brain size was still very similar to that of modern chimpanzees and gorillas. Analysis of the Laetoli footprints give these characteristics of obligate bi-pedalism: pronounced heel strike from deep impressions, lateral transmission of force from the heel to the base of the lateral metatarsal, a well-developed medial longitudinal arch, adducted big toe, and a deep impression for the big toe commensurate with toe-off.

Age and dating techniques

Two dating techniques were used to arrive at the approximate age of the beds that make up the ground layers at Laetoli: potassium-argon dating and stratigraphy. Based on these dating methods, the layers have been named and arranged in the following order (from deepest from the surface to closest to the surface): Lower Laetolil Beds, Upper Laetolil Beds, Lower Ndolanya Beds, Upper Ndolanya Beds, Ogol lavas, Naibadad Beds, Olpiro Beds, and Ngaloba Beds. The upper unit of the Laetolil Beds dated back 3.6 to 3.8 million years ago. The beds are dominantly tuffs and have a maximum thickness of 130 meters. No mammalian fauna were found in the lower unit of the Laetolil Beds, and no date could be assigned to this layer.

The Ndolanya Beds, which are located above the Laetolil Beds and underlie the Ogol lavas, are clearly divisible into upper and lower units separated by a widespread deposit of calcrete up to one meter thick. However, like the Lower Laetolil Beds, no date can be assigned to the Ndolanya Beds. The Ogol lavas date back 2.4 million years. No fauna or artifacts are known from the Naibadad Beds, and they are correlated with a bed layer at Olduvai Gorge based on mineral content. Pleistocene fauna and Acheulean artifacts have been found in the Olpiro Beds. Based on a trachytic tuff which occurs within the beds, the Ngaloba Beds may therefore be dated between 120,000 to 150,000 years BP.

Discoveries

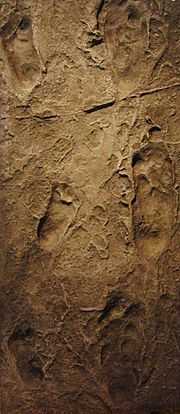

Hominid footprints

The principal discovery is an 80-foot (24-meter) line of hominid fossil footprints, discovered by Mary Leakey and her team in 1976 (and fully excavated by 1978), preserved in powdery volcanic ash originally thought to have been from an eruption of the 20 km distant Sadiman volcano. However, recent study of the Sadiman volcano has shown that it is not a source for the Laetoli Footprints Tuff (Zaitsev et al. 2011). Soft rain cemented the ash-layer (15 cm thick) to tuff without destroying the prints. In time, they were covered by other ash deposits.

The hominid prints were produced by three individuals, one walking in the footprints of the other, making the original tracks difficult to discover. As the tracks lead in the same direction, they might have been produced by a group visiting a waterhole together—but there is nothing to support the common assumption of a nuclear family.

| hominin 1 | hominin 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| length of footprint | 21.5 cm | 18.5 cm |

| width of footprint | 10 cm | 8.8 cm |

| length of pace | 47.2 cm | 28.7 cm |

| reconstructed body-size | 1.34-1.56 m | 1.15-1.34 m |

The footprints demonstrate that the hominids habitually walked upright as there are no knuckle-impressions. The feet do not have the mobile big toe of apes; instead, they have an arch (the bending of the sole of the foot) typical of modern humans. The hominins seem to have moved in a leisurely stroll.

Computer simulations based on information from A. afarensis fossil skeletons and the spacing of the footprints indicate that the hominids were walking at 1.0 m/s or above, which matches human walking speeds.[1] The results of other studies have also supported the theory of a human-like gait.[2]

Other footprints and artifacts

Other prints show the presence of twenty different animal species besides A. afarensis, among them hyenas, wild cats (Machairodus), baboons, wild boars, giraffes, gazelles, rhinos, several kinds of antelopes, hipparions, buffaloes, elephants (of the extinct Deinotherium genus), hares and birds. Rain-prints can be seen as well. Few footprints are superimposed which indicates that they were rapidly covered up. Most of the animals are represented by skeletal remains discovered in the area.

No artifacts have been found in the vicinity, at least within the ancient Laetolil Beds that contain the trackway. However, artifacts from the younger Olpiro and Ngaloba Beds, also preserved at Laetoli, have been found.[3]

Interpretation and significance

Before the discovery of the Laetoli footprints, there was much debate as to what developed first in the evolutionary time line: a larger brain or bipedalism. The discovery of these footprints therefore settled the issue proving that the hominids found at Laetoli were fully bipedal before the evolution of the modern human brain, and were even bipedal close to a million years before the earliest known stone tools.[4] The prints are classified as belonging to Australopithecus afarensis.

Some analysts have noted in their interpretations that the smaller trail bears "telltale signs that suggest whoever left the prints was burdened on one side."[5] This may suggest that a female was carrying an infant on her hip but this cannot be proven for certain.

The footprints themselves were an unlikely discovery because they are almost indistinguishable from modern human footprints, even being almost 4 million years old. It is noted that the toe pattern is much the same as the human foot, which is much different than the feet of chimpanzees and other non bipedal beings. The footprint impression has been interpreted as the same as the modern human stride, with the heel striking first and then a weight transfer to the ball of the foot before pushing off the toes.[6]

Based on stratigraphic analysis, the findings also provide insight into the climate at the time of the making of the footprints. Pliocene sediments show that the environment was more moist and productive than now.[7] Climate changes that caused a shift from forest to grassland environments has a strong correlation with upright posture and bipedalism in humans. This could have initiated the evolution to bipedalism of the hominids found at Laetoli.

Preservation and conservation

In 1979, after observations from the Laetoli footprints were recorded, the footprints were re-buried as a then-novel way of preservation. After re-burial, the site was revegetated by acacia trees. It was feared that the track might have been deteriorating because of root growth. In mid-1992, a GCI-Tanzanian team investigated this by opening a three-by-three meter trench which showed that root growth had in fact done damage to the footprints. However, the part of the trackway that had not been affected by root growth showed exceptional preservation. The success of the experiment led to an increased practice in reburials for preserving excavated sites.[6]

In 1993, measures were taken to prevent erosion. The original trackway was remolded and new casts were made. Since the trackway is too fragile to be remolded, the new replica cast was used to guide re-excavation in the field. A team of specialists re-excavated half of the trackway to record its condition, stabilize the surface, extract dead roots and rebury it with synthetic geotextile materials. This allows the trackway surface to breathe, and protects it against root growth.[6]

Proposals for lifting the track and moving it to an enclosed site have been suggested, but the cost is viewed as outweighing the benefits: the process would require much research, a large amount of money, and there is a risk of loss or damage. Thus, burial seems to be the most effective method of preservation.[6]

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

Further reading

- Mary D. Leakey and J. M. Harris (eds), Laetoli: a Pliocene site in Northern Tanzania (Oxford, Clarendon Press 1987). ISBN 0-19-854441-3.

- Richard L. Hay and Mary D. Leakey, "Fossil footprints of Laetoli." Scientific American, February 1982, 50-57.

References

- ↑ "PREMOG - Supplementry Info". The Laetoli Footprint Trail: 3D reconstruction from texture; archiving, and reverse engineering of early hominin gait. Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Liverpool. 18 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ David A. Raichlen, Adam D. Gordon, William E. H. Harcourt-Smith, Adam D. Foster, Wm. Randall Haas, Jr (2010). "Laetoli Footprints Preserve Earliest Direct Evidence of Human-Like Bipedal Biomechanics". PLoS ONE 5 (3): e9769. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009769. PMC 2842428. PMID 20339543

- ↑ Ndessokia, P. N. S., 1990. The Mammalian Fauna and Archaeology of the Ndolanya and Olpiro Beds, Laetoli, Tanzania. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley

- ↑ Agnew, Neville and Demas, Martha. The Footprints at Laetoli. The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, Spring 1995. <http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/10_1/laetoli.html>

- ↑ WGBH Educational Foundation. Laetoli Footprints. PBS Video, Evolution: Library: Laetoli Footprints, 2001. <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/07/1/l_071_03.html>

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "The Laetoli Footprints". h2g2. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- ↑ Musiba, Charles M. Laetoli Pliocene Paleoecology: A Reanalysis Via Morphological And Behavioral Approaches, 1999

Bibliography

- Archaeologyinfo.com (n.d.) Australopithecus afarensis. Retrieved from http://archaeologyinfo.com/australopithecus-afarensis/

- Ditchfield, P. & Harrison, T. (2011). Sedimentology, Lithostratigraphy and Depositional History of the Laetoli Area. In T. Harrison (Ed.), Paleontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Evolution in Context: Geology, Geochronology, Paleoecology and Paleoenvironment, Vertebrate Paelobiology and Paleoanthropology. 1, pp. 47–76, Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer

- Leakey, M.D. (1981). Discoveries at Laetoli in Northern Tanzania. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association. 92 (2), pp. 81–86.

- Tuttle, R.H., Webb, D.M., & Baksh, M. (1991). Laetoli Toes and Australopithecus afarensis. Human Evolution. 6 (3) pp. 193–200.

- Tuttle, R.H. (2008). Footprint Clues in Hominid Evolution and Forensics: Lessons and Limitations. Ichnos. 15 (3-4), pp. 158–165.

- White, T.D. & Suwa, G. (1987). Hominid footprints at Laetoli: Facts and Interpretations. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 72 (4). pp. 485–514.

- Zaitsev, AN, Wenzel, T, Spratt, J, Williams, TC, Strekopytov, S, Sharygin, VV, Petrov, SV, Golovina, TA, Zaitseva, EO & Markl, G. (2011). Was Sadiman volcano a source for the Laetoli Footprint Tuff? Journal of Human Evolution 61(1) pp. 121–124.

External links

- Footprints to Fill : Flat feet and doubts about makers of the Laetoli tracks - Scientific American Magazine (August 2005)

- Leakey, M. D. and Hay, R. L. - Pliocene footprints in the Laetolil Beds at Laetoli, northern Tanzania - Nature

- Laetoli Footprints - PBS - Evolution

- - film about Ludwig Kohl-Larsen

- - artworks for and about Laetoli

- Footprints From the Past 2009-10-31)

- Sedimentology, Lithostratigraphy and Depositional History of the Laetoli Area (2011) Ditchfeld & Harrison http://www.springerlink.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/content/h119564143150570/fulltext.pdf

- Laetoli Toes and Australopithecus afarensis (1991) Tuttle, Webb, Baksh http://www.springerlink.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/content/u62jqn2p186r7152/fulltext.pdf

- Discoveries at Laetoli in northern Tanzania (1981) Leakey http://www.sciencedirect.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/science?_ob=MiamiImageURL&_cid=277817&_user=99318&_pii=S0016787881800089&_check=y&_origin=gateway&_coverDate=31-Dec-1981&view=c&wchp=dGLzVlV-zSkzk&md5=a7cf44a39140aef5bc4fd70507388848/1-s2.0-S0016787881800089-main.pdf

- Hominid Footprints and Laetoli: Facts and Interpretations (1987) White, Suwa http://dl2af5jf3e.search.serialssolutions.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/?sid=CSA:zooclust-set-c&pid=%3CAN%3EZOOR12300058872%3C%2FAN%3E%26%3CPY%3E1987%3C%2FPY%3E%26%3CAU%3EWhite%2C%20T%2ED%2E%3B%20Suwa%2C%20G%2E%3C%2FAU%3E&issn=0002-9483&volume=72&issue=4&spage=485&epage=514&date=1987&genre=article&aulast=White&auinit=TD&title=American%20Journal%20of%20Physical%20Anthropology&atitle=Hominid%20footprints%20at%20Laetoli%3A%20facts%20and%20interpretations

- The Laetoli Footprints (1996) Agnew, Demas, Leakey http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/stable/pdfplus/2890795.pdf?acceptTC=true

- Footprint Clues in Hominid Evolution and Forensics: Lessons and Limitations (2008) Tuttle http://www.tandfonline.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/doi/pdf/10.1080/10420940802467892

- Description of Australopithecus Afarensis. http://archaeologyinfo.com/australopithecus-afarensis/-Create 3 new sections: Interpretation, controversy of the footprints, and preservation and conservation problems