La Haine

| La Haine | |

|---|---|

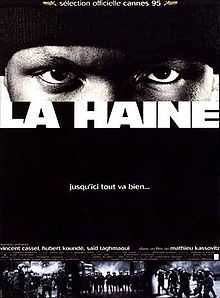

La Haine cover, with the tagline Jusqu'ici tout va bien… ("So far, so good…") | |

| Directed by | Mathieu Kassovitz |

| Produced by | Christophe Rossignon |

| Written by | Mathieu Kassovitz |

| Starring |

Vincent Cassel Hubert Koundé Saïd Taghmaoui |

| Music by | Assassin |

| Cinematography | Pierre Aïm |

| Editing by |

Mathieu Kassovitz Scott Stevenson |

| Distributed by | Canal+ |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | €2,590,000[1] |

| Box office | $309,811 (USA)[2] |

La Haine (French pronunciation: [la ʔɛn], 'hate') is a 1995 French black-and-white drama/suspense film written, co-edited, and directed by Mathieu Kassovitz. It is commonly released under its French title in the English-speaking world, although its U.S. VHS release was entitled Hate. It is about three young friends and their struggle to live in the banlieues of Paris. The title derives from a line spoken by one of them, Hubert: "La haine attire la haine !", "hatred breeds hatred."

Plot

The film depicts approximately 19 consecutive hours in the lives of three friends in their early twenties from immigrant families living in an impoverished multi-ethnic French housing project (a ZUP - zone d'urbanisation prioritaire) in the suburbs of Paris, in the aftermath of a riot. Vinz (Vincent Cassel), who is Jewish, is filled with rage. He sees himself as a gangster ready to win respect by killing a cop, manically practising the role of Travis Bickle from the film Taxi Driver in the mirror secretly. His attitude towards police, for instance, is a simplified, stylized blanket condemnation, even to individual policemen who make an effort to steer the trio clear of troublesome situations. Hubert (Hubert Koundé) is an Afro-French boxer and small time drug dealer, the most mature of the three, whose gymnasium was burned in the riots. The quietest, most thoughtful and wisest of the three, he sadly contemplates the ghetto and the hate around him. He expresses the wish to simply leave this world of violence and hate behind him, but does not know how since he lacks the means to do so. Saïd - Sayid in some English subtitles - (Saïd Taghmaoui) is a Maghrebi who inhabits the middle ground between his two friends' responses to their place in life.

A friend of theirs, Abdel Ichaha, has been brutalized by the police shortly before the riot and lies in a coma. Vinz finds a policeman's .357 Magnum revolver, lost in the riot. He vows that if their friend dies from his injuries, he will use it to kill a cop, and when he hears of Abdel's death he fantasizes carrying out his vengeance.

The three go through an aimless daily routine and struggle to entertain themselves, frequently finding themselves under police scrutiny. They take a train to Paris but encounter many of the same frustrations, and their responses to interactions with both benign and malicious Parisians cause several situations to degenerate to dangerous hostility. A run-in with sadistic plainclothes police, during which Saïd and Hubert are humiliated and racially as well as physically abused, results in their missing the last train home and spending the night on the streets. They go to a roof-top from which they insult skinheads and policemen, before later encountering the same group of racist anti-immigrant skinheads who begin to beat Saïd and Hubert savagely, now that the balance of power has shifted. Vinz suddenly arrives, and his gun allows him to break up the fight; all the skinheads flee except one (portrayed by Kassovitz himself) whom Vinz is about to execute in cold blood. His dream of revenge is thwarted by his reluctance to go through with the deed, and, cleverly goaded by Hubert, he is forced to confront the fact that his true nature is not the heartless gangster he poses as, and he lets the skinhead flee.

Early in the morning, the trio returns to the banlieue and split up to their separate homes, and Vinz turns the gun over to Hubert. However, Vinz and Saïd encounter a plainclothes policeman, whom Vinz had insulted earlier in the day whilst with his friends on a local rooftop. The policeman grabs and threatens Vinz, making reference to the earlier incident on the roof. Hubert rushes to their aid, but as the policeman holding Vinz taunts him with a loaded gun held to Vinz's head, the gun accidentally goes off, killing Vinz instantly. Hubert and the policeman slowly and deliberately point their guns at each other, and as the film cuts to Saïd closing his eyes and cuts to black, a shot is heard on the soundtrack, with no indication of who fired or who may have been hit. This stand-off is underlined by a voice-over of Hubert's slightly modified opening lines ("It's about a society in free fall..."), underlining the fact that, as the lines say, jusqu'ici tout va bien (so far so good); i.e. all seems to be going relatively well until Vinz is killed, and from there no one knows what will happen, a microcosm of French society's descent through hostility into pointless violence.

Cast

- Vincent Cassel as Vinz

- Hubert Koundé as Hubert

- Saïd Taghmaoui as Saïd

- Marc Duret as Inspector Notre Dame

- Abdel Ahmed Ghili as Abdel

- François Levantal as Astérix

- Tadek Lokcinski as Monsieur Toilettes

- Solo as Santo

- Joseph Momo as Ordinary Guy

- Héloïse Rauth as Sarah

- Rywka Wajsbrot as Vinz's Grandmother

- Olga Abrego as Vinz's Aunt

- Laurent Labasse as Cook

- Choukri Gabteni as Saïd's Brother Nordeen

- Nabil Ben Mhamed as Boy Blague

- Benoît Magimel as Benoît

- Medard Niang as Médard

- Arash Mansour as Arash

- Vincent Lindon as Really Drunk Guy

Production

Kassovitz has said that the idea came to him when a young Zairian, Makome M’Bowole was shot in 1993. He was killed at point blank range while in police custody and handcuffed to a radiator. The officer was reported to have been angered by Makome's words, and had been threatening him when the gun went off accidentally.[3] Kassovitz began writing the script on April 6, 1993, the day M'Bowole was shot. He was also inspired by the case of Malik Oussekine, who was shot in 1986 under similar circumstances. Oussekine's death is also referred to in the opening montage of the film.[4] Mathieu Kassovitz included his own experiences; he took part in riots, he acts in a number of scenes and includes his father Peter in another.

The majority of the filming was done in the Parisian suburb of Chanteloup-les-Vignes. Unstaged footage was used for this film, taken from 1986–96; riots still took place during the time of filming. To actually film in the projects, Kassovitz, the production team and the actors, moved there for three months prior to the shooting as well as during actual filming.[5] Due to the film's controversial subject matter, seven or eight local French councils refused to allow the film crew to film on their territory. Kassovitz was forced to temporarily rename the script Droit de Cite (meaning The Free City) and remove the violent final scene in order to secure the necessary permits.[6] Some of the actors were not professional. The film has a documentary feel and includes many situations that were based on real events.[5]

The music of the film was handled by French hardcore rap group Assassin, whose song "Nique the Police" was featured in one of the scenes of the movie. One of the members of Assassin, Mathias Crochon, is the brother of Vincent Cassel, who plays Vinz in the film.[7]

The film is dedicated to those who died while it was being made ("Ce film est dédié à ceux disparus pendant sa fabrication...")

Reception

La Haine was well received. The film was shown at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival where it received a standing ovation. Kassovitz also received the Best Director prize at the festival.[8] The film had a total of 2,042,070 admissions in France where it was the 14th highest grossing film of the year.[1] Based on 14 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an overall approval rating from critics of 100%, with an average score of 8/10.[9] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called the film "raw, vital and captivating".[10] Wendy Ide of The Times stated that La Haine is "One of the most blisteringly effective pieces of urban cinema ever made."[11]

After being well received upon its release in France, Alain Juppé, who was Prime Minister of France at the time, commissioned a special screening of the film for the cabinet, which ministers were required to attend. A spokesman for the Prime Minister said that, despite resenting some of the anti-police themes present in the film, Juppé found La Haine to be "a beautiful work of cinematographic art that can make us more aware of certain realities."[12]

It was ranked #32 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[13]

Awards

- Best Director (1995 Cannes Film Festival) - Mathieu Kassovitz[14]

- Best Editing (César Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz and Scott Stevenson

- Best Film (César Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz

- Best Producer (César Awards) - Christophe Rossignon

- Best Young Film (European Film Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz

- Best Foreign Language Film (Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards)

- Best Director (Lumiere Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz

- Best Film (Lumiere Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz

Home media

La Haine was available on VHS in the United States, but was not released on DVD until the Criterion Collection released a 2-disc edition in 2007. The film has been shown on many Charter Communications Channels. Both HD DVD and Blu-ray versions have also been released in Europe, and Criterion have set an U.S. Blu-ray release for May 2012. The release includes audio commentary by Kassovitz, an introduction by actor Jodie Foster, Ten Years of “La haine,” a documentary that brings together cast and crew a decade after the film’s landmark release, a featurette on the film’s banlieue setting, production footage, and deleted and extended scenes, each with an afterword by Kassovitz.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "La Haine (1995)". JPBox-Office. 1995-05-31. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0113247/business

- ↑ Elstob, Kevin. "Hate (La Haine) review". Film Quarterly (Berkeley, California: University of California Press) 51 (2 (Winter, 1997-1998)): 44–49. ISSN 0015-1386. JSTOR 3697140.

- ↑ http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/642-la-haine-and-after-arts-politics-and-the-banlieue

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "la HAINE". Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/why-the-prime-minister-had-to-see-la-haine-1578297.html

- ↑ http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/642-la-haine-and-after-arts-politics-and-the-banlieue

- ↑ http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/642-la-haine-and-after-arts-politics-and-the-banlieue

- ↑ "La Haine (Hate) (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Kevin (March 8, 1996). "Compelling, Bleak Look at 'Hate'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ Ide, Wendy (August 19, 2004). "La Haine". The Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/why-the-prime-minister-had-to-see-la-haine-1578297.html

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema | 32. La Haine". Empire. 2010. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: La Haine". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ↑ "La Haine". The Criterion Collection.

External links

- La Haine at the Internet Movie Database

- Stanford University Review

- Working Class France..." POV by Matthieu Kassovitz about the 2005 riots in France

- La Haine: Kassovitz vs. Sarkozy Debate between Kassovitz and Nicolas Sarkozy

- Thoughts on the film by director Costa-Gavras

- Criterion Collection Essay by Ginette Vincendeau

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| |||||