LGP-30

The LGP-30, standing for Librascope General Purpose and then Librascope General Precision, was an early off-the-shelf computer. It was manufactured by the Librascope company of Glendale, California (a division of General Precision Inc.), and sold and serviced by the Royal Precision Electronic Computer Company, a joint venture with the Royal McBee division of the Royal Typewriter Company. The LGP-30 was first manufactured in 1956 with a retail price of $47,000.

The LGP-30 was commonly referred to as a desk computer. It was 26 inches (660 mm) deep, 33 inches (840 mm) high, and 44 inches (1120 mm) long, exclusive of the typewriter shelf. The computer weighed approximately 740 pounds (340 kg) and was mounted on sturdy casters which facilitated movement of the computer.

Design

The primary design consultant for the Librascope computer was Stan Frankel, a Manhattan Project veteran and one of the first programmers of ENIAC. He designed a usable computer with a minimal amount of hardware. The single address instruction set had only 16 commands. Not only was the main memory on magnetic drum, but so were the CPU registers, timing information and the master bit clock, each on a dedicated track. The number of vacuum tubes were kept to a minimum by using solid-state diode logic, a bit-serial architecture and multiple usage of each of the 15 flip-flops.

It was a binary, 31 bit word computer with a 4096 word drum memory. Standard inputs were the Flexowriter keyboard and paper tape (ten 6-bit characters/second). The only printing output was the Flexowriter printer (typewriter, working at 10 characters/second). An optional higher speed paper tape reader and punch was available as a separate peripheral.

The LGP-30 required 1500 watts when operating under full load. The power inlet cord was plugged into any standard 115 volt 60 cycle single phase line. The computer contained internal voltage regulation against power line variations of voltages from 95 to 130 volts. In addition to regulation of power line variations, the computer also contained the circuitry required to permit a warm-up stage. This warm-up stage minimized thermal shock to tubes to ensure long component life. The computer contained its own blower unit and directed filtered air, through ducts, to tubes and diodes, in order to ensure component life and proper operation. No expensive air conditioning needed to be installed if operated within a reasonable temperature range.

There were 32 bit locations per drum word, but only 31 were used, permitting a "restoration of magnetic flux in the head" at the 32nd bit time. Since there was only one address per instruction, a method was needed to optimise allocation of operands. Otherwise, each instruction would wait a complete drum (or disk) revolution each time a data reference was made. The LGP-30 provided for operand-location optimization by interleaving the logical addresses on the drum so that two adjacent addresses (e.g., 00 and 01) were separated by nine physical locations. These spaces allowed for operands to be located next to the instructions which use them. There were 64 tracks, each with 64 words (sectors). The time between two adjacent physical words was approximately 0.260 millisecond, and the time between two adjacent addresses was 9 x 0.260 or 2.340 milliseconds. The worst-case access time was 16.66 ms.

Half of the instruction (15 bits) was unused. The unused half could be used for extra instructions, indexing, indirect addressing, or a second (+1) address to locate the next instruction, each of which could increase program performance.

A truly unique feature of the LGP-30 was the way it handled multiply. Despite the LGP-30 being inexpensive, it had built in multiply. Since this was a drum computer and bits needed to be acted on serially as they were read from the drum, as it did each of the additions involved in the multiply, it effectively shifted the operand right, acting as if the binary point was on the left side of the word, as opposed to the right side as most other computers assume. The divide operation worked similarly. It also had an integer multiply but, because the accumulator had 32 bits while memory words had only 31 bits, only even integers could be thus represented.

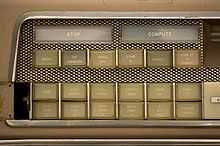

To further reduce costs, the traditional front panel lights showing internal registers were absent. Instead, Librascope mounted a small oscilloscope on the front panel. It displayed the output from the three register read heads, one above the other, allowing the operator to "see" and actually read the bits. Horizontal and vertical size controls let the operator adjust the display to match a plastic overlay engraved with the bit numbers. To read bits the operator counted the up- and down- transitions of the oscilloscope trace.

Unlike other machines of its day, internal data was represented in hexadecimal as opposed to octal, but being a very inexpensive machine it used the physical typewriter keys that correspond to positions 10 to 15 in the type basket[citation needed] for the six non-decimal characters (as opposed to a - f) to represent those values, resulting in 0 - 9 f g j k q w, which was remembered using the phrase "FiberGlass Javelins Kill Quite Well".

Specifications

- Word Length: 31 Bits, including a sign bit, but excluding a blank spacer bit

- Memory Size: 4096 word

- Speed: 0.260 milliseconds access time between two adjacent physical words; access times between two adjacent addresses 2.340 milliseconds.

- Clock Rate: 120 kHz

- Power consumption: 1500 Watts

- Heat dissipation: 5000 BTU/h (1465 Watts)

- Arithmetic element: Three working registers: C the counter register, R the instruction register and A the accumulator register.

- Instruction format: Sixteen instruction using half-word format

- Technology: 113 vacuum tubes and 1350 diodes.

- Number Produced; 320~493

- First Delivery: September, 1956

- Price: $47,000

- Successor: LGP-21

- Achievements: The LGP-30 was one of the first desk-sized computer offering small scale scientific computing. The LGP-30 was quite popular with "half a thousand" units sold, including one at Dartmouth College where students implemented Dartmouth ALGOL 30 on the machine.

ACT-III programming language

The LGP-30 had an "Algol-like"[citation needed] high level language called ACT-III. Every token had to be delimited by an apostrophe, making it hard to read and even harder to prepare tapes:

s1'dim'a'500'm'500'q'500''

index'j'j+1'j-1''

daprt'e'n't'e'r' 'd'a't'a''cr''

rdxit's35''

s2iread'm'1''iread'q'1''iread'd''iread'n''

1';'j''

0'flo'd';'d.''

s3'sqrt'd.';'sqrd.''

1'unflo'sqrd.'i/'10';'sqrd''

2010'print'sqrd.''2000'iprt'sqrd''cr''cr''

...

Starting the machine

The procedure for starting, or "booting" the LGP-30 was one of the most complicated ever devised. First, one snapped the bootstrap paper tape into the console typewriter, a Friden Flexowriter, pressed a lever on the Flexowriter to read an address field and pressed a button on the front panel to transfer the address into a computer register. Then one pressed the lever on the Flexowriter to read the data field and pressed three more buttons on the front panel to store it at the specified address. This process was repeated, maybe six to eight times, and one developed a rhythm:

burrrp, clunk, burrrp, clunk, clunk, clunk, burrrp, clunk, burrrp, clunk, clunk, clunk, burrrp, clunk, burrrp, clunk, clunk, clunk, burrrp, clunk, burrrp, clunk, clunk, clunk, burrrp, clunk, burrrp, clunk, clunk, clunk, burrrp, clunk, burrrp, clunk, clunk, clunk.

The operator then removed the bootstrap tape, snapped in the tape containing the regular loader, carefully arranging it so it wouldn't jam, and pressed a few more buttons to start up the bootstrap program. Once the regular loader was in, the computer was ready to read in a program tape. The regular loader read a more compact format tape than the bootstrap loader. Each block began with a starting address so the tape could be rewound and retried if an error occurred. If any mistakes were made in the process, or if the program crashed and damaged the loader program, the process had to be restarted from the beginning.

Act-III and booting sections from Arnold Reinhold's Computer History page, with permission under GFDL and CC-BY-SA 3.0.

LGP-21

In 1963 Librascope produced a transistorized update to the LGP-30 named the LGP-21. The new computer had 460 transistors and about 300 diodes. It cost only $16,200, one-third the price of its predecessor. Unfortunately it was also about one-third as fast as the earlier computer.

RPC 4000

Another, more powerful successor machine, was the General Precision RPC 4000. Similar to the LGP-30, but transistorized, it featured 8,008 32 bit words of memory drum storage. According to BRL Report 1964 it had 500 transistors and 4,500 diodes and sold for $87,500.

Notable uses

Today, the LGP-30 is remembered as the computer on which Mel Kaye performed a legendary programming task in machine code, retold by Ed Nather in the hacker epic The Story of Mel.[1] This, however, is inaccurate: The feat actually took place on a different machine by the same manufacturer, the RPC-4000. The LGP-30 was also used by Edward Lorenz in his attempt to model changing weather patterns. His discovery that massive differences in forecast could derive from tiny differences in initial data led to him coining the terms strange attractor and butterfly effect, core concepts in chaos theory.

See also

- IBM 650

- Mel Kaye

- List of vacuum tube computers

External links

- Working LGP-30 on display in Stuttgart, Germany

- LGP-30 description

- LGP-21 description

- 1962 advertisement showing both the LGP-30 and RPC-4000

- Story of Stan P. Frankel, designer of the LGP-30, with photos.

- Programming manual

- Warming up the LGP-30 on YouTube

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGP-30. |