Kuril Islands

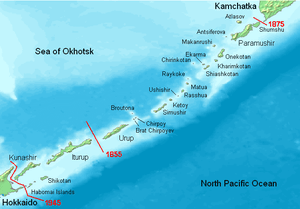

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (/ˈkʊərɪl/, /ˈkjʊərɪl/, or /kjʊˈriːl/; Russian: Кури́льские острова́, tr. Kuril'skie ostrova, IPA: [kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva]; Japanese: くりる Kuriru rettō, (千島列島 Chishima rettō)), in Russia's Sakhalin Oblast region, form a volcanic archipelago that stretches approximately 1,300 km (810 mi) northeast from Hokkaido, Japan, to Kamchatka, Russia, separating the Sea of Okhotsk from the North Pacific Ocean. There are 56 islands and many more minor rocks. It consists of Greater Kuril Ridge and Lesser Kuril Ridge.[1] The total land area is about 15,600 square kilometres (6,000 sq mi)[2] and total population about 19,000.[3]

All of the islands are under the Russian jurisdiction, but Japan claims the two southernmost large islands (Iturup and Kunashir) as part of its territory, as well as Shikotan and the Habomai islets, which has led to the ongoing Kuril Islands dispute.

Nomenclature

The name Kuril originates from the autonym of the aboriginal Ainu, the islands' original inhabitants: "kur", meaning man. It may also be related to names for other islands that have traditionally been inhabited by the Ainu people, such as Kuyi or Kuye for Sakhalin and Kai for Hokkaidō. In Japanese, the Kuril Islands are known as the Chishima Islands (Kanji: 千島列島 Chishima Rettō pronounced [tɕiɕima ɽetːoː], literally, Thousand Islands Archipelago), also known as the Kuriru Islands (Katakana: クリル列島 Kuriru Rettō [kɯɽiɽɯ ɽetːoː], literally, Kuril Archipelago). Once the Russians reached the islands in the 18th century they found a pseudo-etymology from Russian kurit ("курить" - "to smoke") due to the continual fumes and steam above the islands from volcanoes.

Geography

The Kuril Islands form part of the ring of tectonic instability encircling the Pacific ocean referred to as the Ring of Fire. The islands themselves are summits of stratovolcanoes that are a direct result of the subduction of the Pacific Plate under the Okhotsk Plate, which forms the Kuril Trench some 200 kilometres (120 mi) east of the islands. The chain has around 100 volcanoes, some 40 of which are active, and many hot springs and fumaroles. There is frequent seismic activity, including a magnitude 8.5 earthquake in 1963 and one of magnitude 8.3 recorded on November 15, 2006, which resulted in tsunami waves up to 5 feet (1.5 m) reaching the California coast.[4]

The climate on the islands is generally severe, with long, cold, stormy winters and short and notoriously foggy summers. The average annual precipitation is 30–40 inches (760–1,020 mm), most of which falls as snow.

The chain ranges from temperate to sub-Arctic climate types, and the vegetative cover consequently ranges from tundra in the north to dense spruce and larch forests on the larger southern islands. The highest elevations on the islands are Alaid volcano (highest point: 2,339 m or 7,674 ft) on Atlasov Island at the northern end of the chain and Tyatya volcano (1,819 m or 5,968 ft) on Kunashir Island at the southern end.

Landscape types and habitats on the islands include many kinds of beach and rocky shores, cliffs, wide rivers and fast gravelly streams, forests, grasslands, alpine tundra, crater lakes and peat bogs. The soils are generally productive, owing to the periodic influxes of volcanic ash and, in certain places, owing to significant enrichment by seabird guano. However, many of the steep, unconsolidated slopes are susceptible to landslides and newer volcanic activity can entirely denude a landscape.

Marine ecology

Owing to their location along the Pacific shelf edge and the confluence of Okhotsk Sea gyre and the southward Oyashio Current, the Kuril islands are surrounded by waters that are among the most productive in the North Pacific, supporting a wide range and high abundance of marine life.

Invertebrates: Extensive kelp beds surrounding almost every island provide crucial habitat for sea urchins, various mollusks and countless other invertebrates and their associated predators. Many species of squid provide a principal component of the diet of many of the smaller marine mammals and birds along the chain.

Fish: Further offshore, walleye pollock, Pacific cod, several species of flatfish are of the greatest commercial importance. During the 1980s, migratory Japanese sardine was one of the most abundant fish in the summer and the main Pinnipeds were a significant object of harvest for the indigenous populations of the Kuril islands, both for food and materials such as skin and bone. The long term fluctuations in the range and distribution of human settlements along the Kuril island presumably tracked the pinniped ranges. In historical times, fur seals were heavily exploited for their fur in the 19th and early 20th centuries and several of the largest reproductive rookeries, as on Raykoke island, were extirpated. In contrast, commercial harvest of the true seals and Steller Sea Lions has been relatively insignificant on the Kuril islands proper. Since the 1960s there has been essentially no additional harvest and the pinniped populations in the Kuril islands appear to be fairly healthy and in some cases expanding. The notable exception is the now extinct Japanese Sea lion which was known to occasionally haul out on the Kuril islands.

Sea otters were exploited very heavily for their pelts in the 19th century. Indeed, as shown by 19th and 20th century whaling catch and sighting records [5]

Seabirds: The Kuril islands are home to many millions of seabirds, including Northern Fulmars, Tufted Puffins, Murres, Kittiwakes, Guillemots, Auklets, Petrels, Gulls, Cormorants. On many of the smaller islands in summer, where terrestrial predators are absent, virtually every possibly hummock, cliff niche or underneath of boulder is occupied by a nesting bird.

Terrestrial ecology

The composition of terrestrial species on the Kuril islands is dominated by Asian mainland taxa via migration from Hokkaido and Sakhalin Islands and by Kamchatkan taxa from the North. While highly diverse, there is a relatively low level of endemism.

Because of the generally smaller size and isolation of the central islands, few major terrestrial mammals have colonized these, though red and arctic foxes were introduced for the sake of the fur trade in the 1880s. The bulk of the terrestrial mammal biomass is taken up by rodents, many introduced in historical times. The largest southernmost and northernmost islands are inhabited by brown bear, foxes, and martens. Some species of deer are found on the more southerly islands. It is claimed that a wild cat, the Kurilian Bobtail, originates from the Kuril Islands. The bobtail is due to the mutation of a dominant gene. The cat has been domesticated and exported to nearby Russia and bred there, becoming a popular domestic cat.

Among terrestrial birds, ravens, peregrine falcons, some wrens and wagtails are common.

Human settlement history

The Ainu people were early inhabitants of Kuril Islands, although there are few records that pre-date the 17th century. The Japanese administration first took nominal control of the islands in the Edo period of Japan, in the form of claims by the Matsumae clan. It is claimed that the Japanese knew of the northern islands 370 years ago.[6] On "Shōhō Onkuko Ezu", a map of Japan made by the Tokugawa shogunate, in 1644, there are 39 large and small islands shown northeast of the Shiretoko peninsula and Cape Nosappu. The Russian Empire began to advance into the Kurils in the early 18th century. Although the Russians often sent expedition parties for research and hunted sea otters, they never went south of Urup island.[citation needed]

Russian settlements extended as far as Iturup in the 18th century. Parts of the islands south of Iturup were occupied by guards of the Tokugawa shogunate.

In 1811, Russian Captain Vasily Golovnin and his crew, who stopped at Kunashir during their hydrographic survey, were captured by retainers of the Nambu clan, and sent to the Matsumae authorities. Because a Japanese trader, Takadaya Kahei, was also captured by Petr Rikord, Captain of a Russian vessel near Kunashir in 1812, Japan and Russia entered into negotiations to establish the border between the two countries.[citation needed]

The Treaty of Commerce, Navigation and Delimitation was concluded in 1855, and the border was established between Iturup and Urup. This border confirmed that Japanese territory stretched south from Iturup and Russian territory stretched north of Urup. Sakhalin remained a place where people from both countries could live. The Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1875 resulted in Japan relinquishing all rights over Sakhalin in exchange for Russia ceding all of the Kuril Islands south of Kamchatka.

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Gunji, a retired Japanese military man and local settler in Shumshu, led an invading party to the Kamchatka coast. Russia sent reinforcements to the area to capture and intern this group. After the war was over, Japan received fishing rights in Russian waters as part of the Russo-Japanese Fisheries Agreement until 1945.

During their armed intervention in Siberia 1918–1925, Japanese forces from the northern Kurils, along with United States and European forces, occupied southern Kamchatka. Japanese vessels made naval strikes against Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.

The Soviet Union seized southern Sakhalin and the Kuril islands at the end of World War II. Japan maintains a claim to the four southernmost islands of Kunashir, Iturup, Shikotan, and the Habomai rocks, together called the Northern Islands Territories (see Kuril Islands dispute).

Japanese administration

In 1869, the Meiji government established the Colonization Commission in Sapporo to aid in the development of the northern area. Ezo was renamed Hokkaidō and Kita Ezo later received the name of Karafuto. Eleven provinces and 86 districts were founded by Meiji government and were put under the control of feudal clans. Because the Meiji government could not sufficiently cope with Russians moving to south Sakhalin, Japan negotiated with Russia over control of the Kuril Islands, resulting in the Treaty of Saint Petersburg that ceded the eighteen islands north of Uruppu to Japan and all of Sakhalin to Russia.

Road networks and post offices were established on Kunashiri and Etorofu. Life on the islands became more stable when a regular sea route connecting islands with Hokkaidō was opened and a telegraphic system began. At the end of the Taishō period, towns and villages were organized in the northern territories and village offices were established on each island. The Habomai island towns were all part of Habomai Village for example. In other cases the town and village system was not adopted on islands north of Uruppu, which were under direct control of the Nemuro Subprefectural office of the Hokkaidō government.

Each village had a district forestry system, a marine product examination center, salmon hatchery, post office, police station, elementary school, Shinto temple, and other public facilities. In 1930, 8,300 people lived on Kunashiri island and 6,000 on Etorofu island, and most of them were engaged in coastal and high sea fishing.

There were 17,291 Japanese islanders on the Kurils.[citation needed]

World War II

- Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto ordered the meeting of the Imperial Japanese Navy strike force for the Hawaii Operation attack on Pearl Harbor, November 22, 1941 in Tankan or Hitokappu Bay, in Iturup Island, South Kurils. The territory was chosen for its sparse population, lack of foreigners, and constant fog coverage. The Admiral ordered the move to Hawaii on the morning of November 26.

- On July 10, 1943, the first bombardment against the Shumushu and Paramushiro Japanese bases by American forces occurred. From Alexai airfield 8 B-25 Mitchells from the 77th Bombardment Squadron took off, led by Capt James L. Hudelson. This mission principally struck Paramushiro.

- Another mission was flown during September 11, 1943, when Eleventh Air Force dispatched eight B-24 Liberators and 12 B-25s. But now the Japanese were alert and reinforced their defenses. 74 crew members in three B-24s and seven B-25 failed to return. Twenty two men were killed in action, one taken prisoner and 51 interned in Kamchatka, Russia.

- The Eleventh Air Force implemented other bombing missions against the northern Kurils including a strike by six B-24s from the 404th Bombardment Squadron and 16 P-38s from the 54th Fighter Squadron on February 5, 1944.

- Japanese sources report that the Matsuwa military installations were subject to American air strikes between 1943–44.

- The Americans' "Operation Wedlock", diverted Japanese attention north and misled them about U.S. strategy in the Pacific. The plan included air strikes by U.S.A.A.F. and U.S. Navy Bombers and U.S. Navy shore bombardment and submarine operations. Japanese increased their garrison in the north Kurils from 8,000 in 1943 to 41,000 in 1944 and maintained more than 400 aircraft in Kurils and Hokkaidō area in anticipation that the Americans might invade from Alaska.

- American planners had briefly contemplated an invasion of northern Japan from the Aleutian Islands during the fall of 1943 but rejected that idea as too risky and impractical. They considered the use of Boeing B-29 Superfortresses, on Amchitka and Shemya Bases, but rejected that idea, too. The U.S. military maintained interest in these plans when they ordered the expansion of bases in the western Aleutians, and major construction began on Shemya. In 1945, plans were shelved for a possible invasion of Japan via the Northern route.

- In August 18–31, Soviet forces invaded the North and South Kurils. The entire Japanese civilian population of roughly 17,000 was expelled by 1946.

- Between August 24 and September 4, 1945, the Eleventh Air Force of the United States Army Air Force sent two B-24s on reconnaissance missions over North Kuril Islands with intention to take photos of the Soviet occupation in the area. Soviet fighters intercepted and forced them away, a foretaste of the Cold War that lay ahead.

Russian administration

- Severo-Kurilsky District (Severo-Kurilsk)

- Kurilsky District (Kurilsk)

- Yuzhno-Kurilsky District (Yuzhno-Kurilsk)

Current situation

As of 2003, roughly 16,800 people inhabited the Kuril Islands. These include ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Tatars, Nivkhs, and Oroch. Russian Orthodoxy and Islam are the only religions with significant following among the population.[citation needed]

Economy

Fishing is the primary occupation. The islands have strategic and economic value, in terms of fisheries and also mineral deposits of pyrite, sulfur, and various polymetallic ores. There are hopes that oil exploration will provide an economic boost to the islands.[7]

In recent times the economic rise of the Russian Federation has been seen on the Kurils too. The most visible sign of improvement is the new construction in infrastructure. Construction workers are now working vigorously to build a pier and a breakwater in Kitovy Bay, central Iturup, where barges are still a major means of transport sailing between the cove and ships anchored offshore. A new road has been carved through the woods near Kurilsk, the island's biggest village, going to the site of an airport scheduled to open in 2010 at a cost of 1.26 billion rubles (US$44 million).

Gidrostroy, the Kurils' biggest business group with interests in fishing as well as construction and real estate, built its second fish processing factory on Iturup island in 2006, introducing a state-of-the-art conveyor system.

To deal with a rise in the demand of electricity, the local government is also upgrading a state-run geothermal power plant at Mount Baransky, an active volcano, where steam and hot water can be found.[8]

Military

The main Russian force stationed on the islands is the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division, which has its headquarters in Goryachiye Klyuchi on Iturup Island. There are also Border Guard Service troops stationed on the islands. In February 2011, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev called for substantial reinforcements of the Kuril Islands defences following the heating up of the dispute in early 2011.[9]

Atlasov Island

The northernmost, Atlasov Island (Oyakoba in Japanese), is an almost perfect volcanic cone rising sheer out of the sea; it has been praised by the Japanese in haiku, wood-block prints, and other forms, in much the same way as the better-known Mt. Fuji.

List of the islands

While in Russian sources the islands are mentioned for the first time in 1646, the earliest detailed information about them was provided by the explorer Vladimir Atlasov in 1697. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Kuril Islands were explored by Danila Antsiferov, I.Kozyrevsky, Ivan Yevreinov, Fyodor Luzhin, Martin Shpanberg, Adam Johann von Krusenstern, Vasily Golovnin, and Henry James Snow.

From north to south, the main islands are (alternative names given in parentheses):

North Kurils (Kita-chishima / 北千島)

- Shumshu (Russian: Шумшу; Shumushu / 占守島)

- Atlasov (Остров Атласова; Oyakoba, Araido / 阿頼度島)

- Paramushir (Парамушир; Paramushiru, Horomushiro / 幌筵島)

- Antsiferov (Остров Анциферова; Shirinki / 志林規島)

- Makanrushi (Маканруши; Makanru / 磨勘留島)

- Onekotan (Онекотан; Onnekotan / 温禰古丹島)

- Kharimkotan (Харимкотан; Harimukotan, Harumukotan / 春牟古丹島)

- Ekarma (Экарма; Ekaruma / 越渇磨島)

- Chirinkotan (Чиринкотан; 知林古丹島)

- Shiashkotan (Шиашкотан; Shasukotan / 捨子古丹島)

- Raikoke (Райкоке; 雷公計島)

- Matua (Матуа; Matsuwa, Matsua / 松輪島)

- Rasshua or Rasshya (Расшуа; Rasutsuwa, Rashowa, Rasuwa / 羅処和島)

- Ushishir (Ушишир; Ushishiru / 宇志知島)

- Ketoy (Кетой; Ketoi / 計吐夷島)

- Simushir (Симушир; Shimushiru, Shinshiru / 新知島)

- Broutona (Остров Броутона; Buroton, Makanruru / 武魯頓島)

- Chirpoy (Чирпой; Chirihoi, Chieruboi / 知理保以島)

- Brat Chirpoyev (Брат Чирпоев; Chirihoinan / 知理保以南島)

- Urup (Уруп; Uruppu / 得撫島)

South Kurils (Minami-chishima / 南千島)

- Iturup (Итуруп; Etorofu / 択捉島)

- Kunashir (Кунашир; Kunashiri / 国後島)

- Shikotan (Шикотан; 色丹島)

- Khabomai Rocks (Южно-Курильская гряда; Habomai Shotō / 歯舞諸島)

See also

- 2006 Kuril Islands earthquake

- 2006 Kuril Islands tsunami

- 2007 Kuril Islands earthquake

- Chishima Province

- Evacuation of Karafuto and Kuriles

- Invasion of the Kuril Islands

- Governor-General of Karafuto

- Karafuto

- Organization of Hokkai (North) Army

- Organization of Karafuto Fortress

- Organization of Kita and Minami Fortresses

- Political divisions of Karafuto Prefecture

- Kuril Islands dispute

References

- ↑ GSE

- ↑ http://www.sakhalin.ru/Engl/Region/geography.htm

- ↑ "Kuril Islands: factfile". The Daily Telegraph (London). November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Central Kuril Island Tsunami in Crescent City, California University of Southern California

- ↑ Clapham, P. J.; C. Good, S. E. Quinn, R. R. Reeves, J. E. Scarff and R.L. Brownell, Jr. (2004). "Distribution of North Pacific". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 6 (1): 1–6.

- ↑ Stephan, John J (1974). The Kuril Islands. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 50–56.

- ↑ "It was hoped that the proceeds from the ongoing projects would help to alleviate the high level of poverty in the region". Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia, s.v. Sakhalin Oblast" (Europa Publications) 2003.

- ↑ Islands disputed with Japan feel Russia's boom - The China Post

- ↑ "Russia moves to defend Kuril Islands claim." RIA Novosti, 9 February 2011.

Further reading

- Gorshkov, G. S. Volcanism and the Upper Mantle Investigations in the Kurile Island Arc. Monographs in geoscience. New York: Plenum Press, 1970. ISBN 0-306-30407-4

- Krasheninnikov, Stepan Petrovich, and James Greive. The History of Kamtschatka and the Kurilski Islands, with the Countries Adjacent. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1963.

- Rees, David. The Soviet Seizure of the Kuriles. New York: Praeger, 1985. ISBN 0-03-002552-4

- Takahashi, Hideki, and Masahiro Ōhara. Biodiversity and Biogeography of the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin. Bulletin of the Hokkaido University Museum, no. 2-. Sapporo, Japan: Hokkaido University Museum, 2004.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. 2006. ISBN 067402241.

- Alan Catharine and Denis Cleary. Unwelcome Company. A fiction thriller novel set in 1984 Tokyo and the Kuriles featuring a light aircraft crash and escape from Russian-held territory. On Kindle.

External links

- http://depts.washington.edu/ikip/index.shtml (Kuril Island Biocomplexity Project)

- Kuril Islands at Ocean Dots.com at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010) (includes space imagery)

- Kuril Islands at Natural Heritage Protection Fund

- The International Kuril Island Project

- http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/russia/territory/index.html

- Chishima: Frontiers of San Francisco Treaty in Hokkaido Short film on the disputed islands from a Japanese perspective

- USGS Map showing location of Magnitude 8.3 Earthquake 46.616°N, 153.224°E Kuril Islands region, November 15, 2006 11:14:16 UTC

- Pictures of Cats - Kurilian Bobtail

- Pictures of Kuril Islands

Coordinates: 46°30′N 151°30′E / 46.500°N 151.500°E