Knights Templar

| Knights Templar Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Salomonici | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | c. 1119–1312 |

| Allegiance | The Pope |

| Type |

Western Christian military order Christian finance |

| Role | Protection of Christian Pilgrims |

| Size | 15,000–20,000 members at peak, 10% of whom were knights[2][3] |

| Headquarters | Temple Mount, Jerusalem |

| Nickname | Order of the Temple |

| Patron | St. Bernard of Clairvaux |

| Motto | Non nobis Domine, non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam (Not unto us, O Lord, not unto us, but unto thy Name give glory) |

| Attire | White mantle with a red cross |

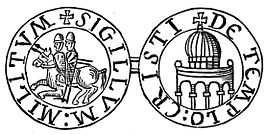

| Mascot | Two knights riding a single horse |

| Engagements |

The Crusades, including: Siege of Ascalon (1153), Battle of Montgisard (1177) Battle of Marj Ayyun (1179) Battle of Hattin (1187), Siege of Acre (1190–1191), Battle of Arsuf (1191), Siege of Al-Dāmūs (1210) Battle of Legnica (1241), Siege of Acre (1291) Reconquista |

| Commanders | |

| First Grand Master | Hugues de Payens |

| Last Grand Master | Jacques de Molay |

This article is part of or related |

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Latin: Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Salomonici), commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple (French: Ordre du Temple or Templiers) or simply as Templars, were among the most wealthy and powerful of the Western Christian military orders[4] and were among the most prominent actors of the Christian finance. The organization existed for nearly two centuries during the Middle Ages.

Officially endorsed by the Catholic Church around 1129, the Order became a favoured charity throughout Christendom and grew rapidly in membership and power. Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades.[5] Non-combatant members of the Order managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom,[6] innovating financial techniques that were an early form of banking,[7][8] and building fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land.

The Templars' existence was tied closely to the Crusades; when the Holy Land was lost, support for the Order faded. Rumours about the Templars' secret initiation ceremony created mistrust and King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Order, took advantage of the situation. In 1307, many of the Order's members in France were arrested, tortured into giving false confessions, and then burned at the stake.[9] Under pressure from King Philip, Pope Clement V disbanded the Order in 1312. The abrupt disappearance of a major part of the European infrastructure gave rise to speculation and legends, which have kept the "Templar" name alive into the modern day.

History

Rise

After the First Crusade recaptured Jerusalem in 1099, many Christian pilgrims travelled to visit what they referred to as the Holy Places. However, though the city of Jerusalem was under relatively secure control, the rest of Outremer was not. Bandits abounded, and pilgrims were routinely slaughtered, sometimes by the hundreds, as they attempted to make the journey from the coastline at Jaffa into the Holy Land.[10]

In 1120, the French knight Hugues de Payens approached King Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem and proposed creating a monastic order for the protection of these pilgrims. King Baldwin and Patriarch Warmund agreed to the request, probably at the Council of Nablus in January 1120, and the king granted the Templars a headquarters in a wing of the royal palace on the Temple Mount in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque.[11] The Temple Mount had a mystique because it was above what was believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon.[5][12] The Crusaders therefore referred to the Al Aqsa Mosque as Solomon's Temple, and it was from this location that the new Order took the name of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, or "Templar" knights. The Order, with about nine knights including Godfrey de Saint-Omer and André de Montbard, had few financial resources and relied on donations to survive. Their emblem was of two knights riding on a single horse, emphasising the Order's poverty.[13]

The impoverished status of the Templars did not last long. They had a powerful advocate in Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, a leading Church figure and a nephew of André de Montbard, one of the founding knights. Bernard put his weight behind them and wrote persuasively on their behalf in the letter 'In Praise of the New Knighthood',[14][15] and in 1129, at the Council of Troyes, he led a group of leading churchmen to officially approve and endorse the Order on behalf of the Church. With this formal blessing, the Templars became a favoured charity throughout Christendom, receiving money, land, businesses, and noble-born sons from families who were eager to help with the fight in the Holy Land. Another major benefit came in 1139, when Pope Innocent II's papal bull Omne Datum Optimum exempted the Order from obedience to local laws. This ruling meant that the Templars could pass freely through all borders, were not required to pay any taxes, and were exempt from all authority except that of the pope.[16]

With its clear mission and ample resources, the Order grew rapidly. Templars were often the advance force in key battles of the Crusades, as the heavily armoured knights on their warhorses would set out to charge at the enemy, in an attempt to break opposition lines. One of their most famous victories was in 1177 during the Battle of Montgisard, where some 500 Templar knights helped several thousand infantry to defeat Saladin's army of more than 26,000 soldiers.[17]

A Templar Knight is truly a fearless knight, and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armour of faith, just as his body is protected by the armour of steel. He is thus doubly armed, and need fear neither demons nor men."

De Laude Novae Militae—In Praise of the New Knighthood[18]

Although the primary mission of the Order was military, relatively few members were combatants. The others acted in support positions to assist the knights and to manage the financial infrastructure. The Templar Order, though its members were sworn to individual poverty, was given control of wealth beyond direct donations. A nobleman who was interested in participating in the Crusades might place all his assets under Templar management while he was away. Accumulating wealth in this manner throughout Christendom and the Outremer, the Order in 1150 began generating letters of credit for pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land: pilgrims deposited their valuables with a local Templar preceptory before embarking, received a document indicating the value of their deposit, then used that document upon arrival in the Holy Land to retrieve their funds. This innovative arrangement was an early form of banking and may have been the first formal system to support the use of cheques; it improved the safety of pilgrims by making them less attractive targets for thieves, and also contributed to the Templar coffers.[5][19]

Based on this mix of donations and business dealing, the Templars established financial networks across the whole of Christendom. They acquired large tracts of land, both in Europe and the Middle East; they bought and managed farms and vineyards; they built churches and castles; they were involved in manufacturing, import and export; they had their own fleet of ships; and at one point they even owned the entire island of Cyprus. The Order of the Knights Templar arguably qualifies as the world's first multinational corporation.[17][20][21]

Decline

In the mid-12th century, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The Muslim world had become more united under effective leaders such as Saladin, and dissension arose among Christian factions in and concerning the Holy Land. The Knights Templar were occasionally at odds with the two other Christian military orders, the Knights Hospitaller and the Teutonic Knights, and decades of internecine feuds weakened Christian positions, politically and militarily. After the Templars were involved in several unsuccessful campaigns, including the pivotal Battle of the Horns of Hattin, Jerusalem was captured by Saladin's forces in 1187. The Crusaders regained the city in 1229, without Templar aid, but held it only briefly. In 1244, the Khwarezmi Turks recaptured Jerusalem, and the city did not return to Western control until 1917 when the British captured it from the Ottoman Turks.[22]

The Templars were forced to relocate their headquarters to other cities in the north, such as the seaport of Acre, which they held for the next century. It was lost in 1291, followed by their last mainland strongholds, Tortosa (Tartus in what is now Syria), and Atlit in present-day Israel. Their headquarters then moved to Limassol on the island of Cyprus,[23] and they also attempted to maintain a garrison on tiny Arwad Island, just off the coast from Tortosa. In 1300, there was some attempt to engage in coordinated military efforts with the Mongols[24] via a new invasion force at Arwad. In 1302 or 1303, however, the Templars lost the island to the Egyptian Mamluks in the Siege of Arwad. With the island gone, the Crusaders lost their last foothold in the Holy Land.[17][25]

With the Order's military mission now less important, support for the organisation began to dwindle. The situation was however complex, as over the two hundred years of their existence, the Templars had become a part of daily life throughout Christendom.[26] The organisation's Templar Houses, hundreds of which were dotted throughout Europe and the Near East, gave them a widespread presence at the local level.[3] The Templars still managed many businesses, and many Europeans had daily contact with the Templar network, such as by working at a Templar farm or vineyard, or using the Order as a bank in which to store personal valuables. The Order was still not subject to local government, making it everywhere a "state within a state"—its standing army, though it no longer had a well-defined mission, could pass freely through all borders. This situation heightened tensions with some European nobility, especially as the Templars were indicating an interest in founding their own monastic state, just as the Teutonic Knights had done in Prussia[19] and the Knights Hospitaller were doing with Rhodes.[27]

Arrests, charges and dissolution

In 1305, the new Pope Clement V, based in France, sent letters to both the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay and the Hospitaller Grand Master Fulk de Villaret to discuss the possibility of merging the two Orders. Neither was amenable to the idea, but Pope Clement persisted, and in 1306 he invited both Grand Masters to France to discuss the matter. De Molay arrived first in early 1307, but de Villaret was delayed for several months. While waiting, De Molay and Clement discussed criminal charges that had been made, it seems, two years prior by an ousted Templar and had been taken up by the king of France and his ministers. It was generally agreed that the charges were false, but Clement sent King Philip IV of France a written request for assistance in the investigation. According to some historians, King Philip, who was already deeply in debt to the Templars from his war with the English, decided to seize upon the rumors for his own purposes. He began pressuring the Church to take action against the Order, as a way of freeing himself from his debts.[28] Recent studies emphasize the political and religious motivations of the French king. It seems that, with the “discovery” and repression of the “Templars' heresy,” the Capetian monarchy claimed for itself the mystic foundations of the papal theocracy. The Temple case was the last step of a process of appropriating these foundations, which had begun with the Franco-papal rift at the time of Boniface VIII. Being the ultimate defender of the Catholic faith, the Capetian king was invested with a Christlike function that put him above the pope: what was at stake in the Templars' trial was the establishment of a "royal theocracy".[29]

On Friday, 13 October 1307 (a date sometimes spuriously linked with the origin of the Friday the 13th superstition)[30][31] Philip ordered de Molay and scores of other French Templars to be simultaneously arrested. The arrest warrant started with the phrase : "Dieu n'est pas content, nous avons des ennemis de la foi dans le Royaume" ["God is not pleased. We have enemies of the faith in the kingdom"].[32] The Templars were charged with numerous offences (including apostasy, idolatry, heresy, obscene rituals and homosexuality, financial corruption and fraud, and secrecy).[33] Many of the accused confessed to these charges under torture, and these confessions, even though obtained under duress, caused a scandal in Paris. All interrogations were recorded on a thirty metre long parchment, kept at the "Archives nationales" in Paris. The prisoners were coerced to confess that they had spat on the Cross : "Moi Raymond de La Fère, 21 ans, reconnais que (J'ai) craché trois fois sur la Croix, mais de bouche et pas de coeur" (free translation : "I, Raymond de La Fère, 21 years old, admit that I have spat three times on the Cross, but only from my mouth and not from my heart"). The Templars were accused of idolatry.[34]

After more bullying from Philip, Pope Clement then issued the papal bull Pastoralis Praeeminentiae on 22 November 1307, which instructed all Christian monarchs in Europe to arrest all Templars and seize their assets.[35] Pope Clement called for papal hearings to determine the Templars' guilt or innocence, and once freed of the Inquisitors' torture, many Templars recanted their confessions. Some had sufficient legal experience to defend themselves in the trials, but in 1310 Philip blocked this attempt, using the previously forced confessions to have dozens of Templars burned at the stake in Paris.[36][37]

With Philip threatening military action unless the pope complied with his wishes, Pope Clement finally agreed to disband the Order, citing the public scandal that had been generated by the confessions. At the Council of Vienne in 1312, he issued a series of papal bulls, including Vox in excelso, which officially dissolved the Order, and Ad providam, which turned over most Templar assets to the Hospitallers.[38]

As for the leaders of the Order, the elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who had confessed under torture, retracted his confession. Geoffroi de Charney, Preceptor of Normandy, also retracted his confession and insisted on his innocence. Both men were declared guilty of being relapsed heretics, and they were sentenced to burn alive at the stake in Paris on 18 March 1314. De Molay reportedly remained defiant to the end, asking to be tied in such a way that he could face the Notre Dame Cathedral and hold his hands together in prayer.[39] According to legend, he called out from the flames that both Pope Clement and King Philip would soon meet him before God. His actual words were recorded on the parchment as follows : "Dieu sait qui a tort et a péché. Il va bientot arriver malheur à ceux qui nous ont condamnés à mort" (free translation : "God knows who is wrong and has sinned. Soon a calamity will occur to those who have condemned us to death").[32] Pope Clement died only a month later, and King Philip died in a hunting accident before the end of the year.[40][41][42]

With the last of the Order's leaders gone, the remaining Templars around Europe were either arrested and tried under the Papal investigation (with virtually none convicted), absorbed into other military orders such as the Knights Hospitaller, or pensioned off and allowed to live out their days peacefully. By papal decree, the property of the Templars was transferred to the Order of Hospitallers, which also absorbed many of the Templars' members. In effect, the dissolution of the Templars could be seen as the merger of the two rival orders.[43] Some may have fled to other territories outside Papal control, such as excommunicated Scotland or to Switzerland. Templar organisations in Portugal simply changed their name, from Knights Templar to Knights of Christ.[44]

Chinon Parchment

In September 2001, a document known as the "Chinon Parchment" dated 17–20 August 1308 was discovered in the Vatican Secret Archives by Barbara Frale, apparently after having been filed in the wrong place in 1628. It is a record of the trial of the Templars and shows that Clement absolved the Templars of all heresies in 1308 before formally disbanding the Order in 1312,[45] as did another Chinon Parchment dated 20 August 1308 addressed to Philip IV of France, also mentioning that all Templars that had confessed to heresy were "restored to the Sacraments and to the unity of the Church". This other Chinon Parchment has been well known to historians [46][47][48] having been published by Étienne Baluze in 1693,[49] and by Pierre Dupuy in 1751.[50]

The current position of the Roman Catholic Church is that the medieval persecution of the Knights Templar was unjust, that nothing was inherently wrong with the Order or its Rule, and that Pope Clement was pressed into his actions by the magnitude of the public scandal and by the dominating influence of King Philip IV, who was Clement's relative.[51][52]

Organization

The Templars were organised as a monastic order similar to Bernard's Cistercian Order, which was considered the first effective international organization in Europe.[53] The organizational structure had a strong chain of authority. Each country with a major Templar presence (France, England, Aragon, Portugal, Poitou, Apulia, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch, Anjou, Hungary, and Croatia)[54] had a Master of the Order for the Templars in that region.

All of them were subject to the Grand Master, appointed for life, who oversaw both the Order's military efforts in the East and their financial holdings in the West. The Grand Master exercised his authority via the visitors-general of the order, who were knights specially appointed by the Grand Master and convent of Jerusalem to visit the different provinces, correct malpractices, introduce new regulations, and resolve important disputes. The visitors-general had the power to remove knights from office and to suspend the Master of the province concerned.

No precise numbers exist, but it is estimated that at the Order's peak there were between 15,000 and 20,000 Templars, of whom about a tenth were actual knights.[2][3]

Ranks within the order

Three main ranks

There was a threefold division of the ranks of the Templars: the noble knights, the non-noble sergeants, and the chaplains. The Templars did not perform knighting ceremonies, so any knight wishing to become a Knight Templar had to already be a knight.[55] They were the most visible branch of the order, and wore the famous white mantles to symbolize their purity and chastity.[56] They were equipped as heavy cavalry, with three or four horses and one or two squires. Squires were generally not members of the Order but were instead outsiders who were hired for a set period of time. Beneath the knights in the Order and drawn from non-noble families were the sergeants.[57] They brought vital skills and trades such as blacksmithing and building, and administered many of the Order's European properties. In the Crusader States, they fought alongside the knights as light cavalry with a single horse.[58] Several of the Order's most senior positions were reserved for sergeants, including the post of Commander of the Vault of Acre, who was the de facto Admiral of the Templar fleet. The sergeants wore black or brown. From 1139, chaplains constituted a third Templar class. They were ordained priests who cared for the Templar's' spiritual needs.[59] All three classes of brother wore the Order's red cross patty.[60]

Grand Masters

Starting with founder Hugues de Payens in 1118–1119, the Order's highest office was that of Grand Master, a position which was held for life, though considering the martial nature of the Order, this could mean a very short tenure. All but two of the Grand Masters died in office, and several died during military campaigns. For example, during the Siege of Ascalon in 1153, Grand Master Bernard de Tremelay led a group of 40 Templars through a breach in the city walls. When the rest of the Crusader army did not follow, the Templars, including their Grand Master, were surrounded and beheaded.[61] Grand Master Gérard de Ridefort was beheaded by Saladin in 1189 at the Siege of Acre.

The Grand Master oversaw all of the operations of the Order, including both the military operations in the Holy Land and Eastern Europe and the Templars' financial and business dealings in Western Europe. Some Grand Masters also served as battlefield commanders, though this was not always wise: several blunders in de Ridefort's combat leadership contributed to the devastating defeat at the Battle of Hattin. The last Grand Master was Jacques de Molay, burned at the stake in Paris in 1314 by order of King Philip IV.[37]

Behaviour and dress

It was Bernard de Clairvaux and founder Hugues de Payens who devised the specific code of behaviour for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses defined the ideal behaviour for the Knights, such as the types of garments they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and not have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. A Master of the Order was assigned "4 horses, and one chaplain-brother and one clerk with three horses, and one sergeant brother with two horses, and one gentleman valet to carry his shield and lance, with one horse."[62] As the Order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses was expanded to several hundred in its final form.[63][64]

The knights wore a white surcoat with a red cross and a white mantle also with a red cross; the sergeants wore a black tunic with a red cross on the front and a black or brown mantle.[65][66] The white mantle was assigned to the Templars at the Council of Troyes in 1129, and the cross was most probably added to their robes at the launch of the Second Crusade in 1147, when Pope Eugenius III, King Louis VII of France, and many other notables attended a meeting of the French Templars at their headquarters near Paris.[67][68][69] According to their Rule, the knights were to wear the white mantle at all times, even being forbidden to eat or drink unless they were wearing it.[70]

The red cross that the Templars wore on their robes was a symbol of martyrdom, and to die in combat was considered a great honor that assured a place in heaven.[71] There was a cardinal rule that the warriors of the Order should never surrender unless the Templar flag had fallen, and even then they were first to try to regroup with another of the Christian orders, such as that of the Hospitallers. Only after all flags had fallen were they allowed to leave the battlefield.[72] This uncompromising principle, along with their reputation for courage, excellent training, and heavy armament, made the Templars one of the most feared combat forces in medieval times.[73]

Initiation,[74] known as Reception (receptio) into the Order, was a profound commitment and involved a solemn ceremony. Outsiders were discouraged from attending the ceremony, which aroused the suspicions of medieval inquisitors during the later trials.

New members had to willingly sign over all of their wealth and goods to the Order and take vows of poverty, chastity, piety, and obedience.[75] Most brothers joined for life, although some were allowed to join for a set period. Sometimes a married man was allowed to join if he had his wife's permission,[66] but he was not allowed to wear the white mantle.[76]

Legacy

With their military mission and extensive financial resources, the Knights Templar funded a large number of building projects around Europe and the Holy Land. Many of these structures are still standing. Many sites also maintain the name "Temple" because of centuries-old association with the Templars.[77] For example, some of the Templars' lands in London were later rented to lawyers, which led to the names of the Temple Bar gateway and the Temple tube station. Two of the four Inns of Court which may call members to act as barristers are the Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

Distinctive architectural elements of Templar buildings include the use of the image of "two knights on a single horse", representing the Knights' poverty, and round buildings designed to resemble the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.[78]

Modern organizations

The story of the persecution and sudden dissolution of the secretive yet powerful medieval Templars has drawn many other groups to use alleged connections with the Templars as a way of enhancing their own image and mystery.[79] There is no clear historical connection between the Knights Templar, which were dismantled in the Rolls of the Catholic Church in 1309 with the martyrdom of Jacques de Molay, and any of the modern organizations, of which, except for the Scottish Order, the earliest emerged publicly in the 18th century.[80][81][82][83] There is often public confusion and many overlook the 400-year gap. However, in 1853, Napoleon III officially recognized the OSMTH. The Order operates on the basis of the traditions of the medieval Knights Templar, celebrating the spirit of, but not claiming direct descent from the ancient Order founded by Hugues de Payens in 1118 and dissolved by Pope Clement V in 1312.

Freemasonry

Since at least the 18th century Freemasonry has incorporated Templar symbols and rituals in a number of Masonic bodies,[5] most notably, the "Order of the Temple" the final order joined in "The United Religious, Military and Masonic Orders of the Temple and of St John of Jerusalem, Palestine, Rhodes and Malta" commonly known as the Knights Templar. One theory of the origins of Freemasonry claims direct descent from the historical Knights Templar through its final fourteenth-century members who took refuge in Scotland whose King, Robert the Bruce was excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church at the time, or in Portugal where the order changed its name to Knights of Christ, other members having joined Knights of St. John. There have even been claims that some of the Templars who made it to Scotland contributed to the Scots' victory at Bannockburn. This theory is usually deprecated on grounds of lack of evidence, by both Masonic authorities[84] and historians.[85]

The Roman Catholic Church has historically opposed Freemasonry since it began to emerge, under the belief the group is a "Secret Society" and has a deeply hidden agenda that opposes the church and its beliefs. Members of the Church found to be Freemasons were in the early 20th Century, commonly excommunicated. This has often led to the misguided belief that the Church somehow also opposed the Knights Templar, however the Church makes distinction between the Templars, a public monastic order, and "Secret Societies". Excommunication as an action taken against Catholics who were found to be Freemason, was lifted by Pope John Paul II in the 1980s, however in the same Papal Bull he reiterated his predecessors strong opposition to Freemasonry, stating that any person who is involved in a secret society and takes communion is putting their soul in grave danger.

Legends and relics

The Knights Templar have become associated with legends concerning secrets and mysteries handed down to the select from ancient times. Rumors circulated even during the time of the Templars themselves. Freemasonic writers added their own speculations in the 19th century, and further fictional embellishments have been added in popular novels such as Ivanhoe, Foucault's Pendulum, The Lost symbol, and The Da Vinci Code;[5] modern movies such as National Treasure and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade; and video games such as Assassin's Creed, The Secret World and Broken Sword.[86]

Many of the Templar legends are connected with the Order's early occupation of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and speculation about what relics the Templars may have found there, such as the Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant.[5][19][73][87] That the Templars were in possession of some relics is certain. Many churches still display holy relics such as the bones of a saint, a scrap of cloth once worn by a holy man, or the skull of a martyr; the Templars did the same. They were documented as having a piece of the True Cross, which the Bishop of Acre carried into battle at the disastrous Horns of Hattin.[88] When the battle was lost, Saladin captured the relic, which was then ransomed back to the Crusaders when the Muslims surrendered the city of Acre in 1191.[89] The Templars were also rumored to possess the head of Saint Euphemia of Chalcedon,[90] and the subject of relics came up during the Inquisition of the Templars, as several trial documents refer to the supposed worship of an idol of some type, referred to in some cases as a cat, a bearded head, or in some cases as Baphomet. This accusation of idol worship levied against the Templars has also led to the modern mistaken belief by some that the Templars practiced witchcraft.[91] However, modern scholars generally explain the name Baphomet from the trial documents as simply a French misspelling of the name Mahomet (Muhammad).[5][92]

The Holy Grail quickly became associated with the Templars, even in the 12th century. The first Grail romance, Le Conte du Graal, was written around 1180 by Chrétien de Troyes, who came from the same area where the Council of Troyes had officially sanctioned the Templars' Order. Perhaps twenty years later Parzival, Wolfram von Eschenbach's version of the tale, refers to knights called "Templeisen" guarding the Grail Kingdom.[93] Another hero of the Grail quest, Sir Galahad (a 13th-century literary invention of monks from St. Bernard's Cistercian Order) was depicted bearing a shield with the cross of Saint George, similar to the Templars' insignia: this version presented the Holy Grail as a Christian relic. A legend developed that since the Templars had their headquarters at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, they must have excavated in search of relics, found the Grail, and then proceeded to keep it in secret and guard it with their lives. However, in the extensive documents of the Templar inquisition there was never a single mention of anything like a Grail relic,[17] let alone its possession by the Templars, nor is there any evidence that a Templar wrote a Grail Romance.[94] In reality, most mainstream scholars agree that the story of the Grail was just that, a literary fiction that began circulating in medieval times.[5][19]

Another legendary object that is claimed to have some connection with the Templars is the Shroud of Turin. In 1357, the shroud was first publicly displayed by the widow of a nobleman known as Geoffrey of Charney,[95] described by some sources as being a member of the family of the grandson of Geoffroi de Charney, who was burned at the stake with De Molay.[96] The shroud's origins are still a matter of controversy, but in 1988, a carbon dating analysis concluded that the shroud was made between 1260 and 1390, a span that includes the last half-century of the Templars' existence.[97] The validity of the dating methodology has subsequently been called into question, and the age of the shroud is still the subject of much debate[98]

References

Notes

- ↑ as reproduced in T. A. Archer, The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1894), p. 176. The design with the two knights on a horse and the inscription SIGILLVM MILITVM XRISTI is attested in 1191, see Jochen Burgtorf, The central convent of Hospitallers and Templars: history, organization, and personnel (1099/1120-1310), Volume 50 of History of warfare (2008), ISBN 978-90-04-16660-8, pp. 545-546.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Burman, p. 45.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Barber, in "Supplying the Crusader States" says, "By Molay's time the Grand Master was presiding over at least 970 houses, including commanderies and castles in the east and west, serviced by a membership which is unlikely to have been less than 7,000, excluding employees and dependents, who must have been seven or eight times that number."

- ↑ Malcolm Barber, The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-42041-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 The History Channel, Decoding the Past: The Templar Code, 7 November 2005, video documentary written by Marcy Marzuni.

- ↑ Selwood, Dominic (2002). Knights of the Cloister. Templars and Hospitallers in Central-Southern Occitania 1100-1300. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0851158285.

- ↑ Martin, p. 47.

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 4.

- ↑ Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars. Cambridge University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-521-45727-0.

- ↑ Burman, pp. 13, 19.

- ↑ Selwood, Dominic. "Birth of the Order". Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Barber, The New Knighthood, p. 7.

- ↑ Read, The Templars. p. 91.

- ↑ Selwood, Dominic. "The Knights Templar 4: St Bernard of Clairvaux". Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Selwood, Dominic (1996). 'Quidam autem dubitaverunt: the Saint, the Sinner and a Possible Chronology', in Autour de la Première Croisade. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. pp. 221–230. ISBN 2859443088.

- ↑ Burman, p. 40.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 The History Channel, Lost Worlds: Knights Templar, July 10, 2006, video documentary written and directed by Stuart Elliott.

- ↑ Stephen A. Dafoe. "In Praise of the New Knighthood". TemplarHistory.com. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Sean Martin, The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order, 2005. ISBN 1-56025-645-1.

- ↑ Ralls, Karen (2007). Knights Templar Encyclopedia. Career Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-56414-926-8.

- ↑ Benson, Michael (2005). Inside Secret Societies. Kensington Publishing Corp. p. 90.

- ↑ Martin, p. 99.

- ↑ Martin, p. 113.

- ↑ Demurger, p.139 "During four years, Jacques de Molay and his order were totally committed, with other Christian forces of Cyprus and Armenia, to an enterprise of reconquest of the Holy Land, in liaison with the offensives of Ghazan, the Mongol Khan of Persia.

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 201. "The Templars retained a base on Arwad island (also known as Ruad island, formerly Arados) off Tortosa (Tartus) until October 1302 or 1303, when the island was recaptured by the Mamluks."

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 5.

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 237.

- ↑ Barber, Trial of the Templars, 2nd ed. "Recent Historiography on the Dissolution of the Temple". In the second edition of his book, Barber summarises the views of many different historians, with an overview of the modern debate on Philip's precise motives.

- ↑ Julien Théry, "A Heresy of State : Philip the Fair, the Trial of the ‘Perfidious Templars’, and the Ponticalization of the French Monarchy", Journal of Religious Medieval Cultures 39/2 (2013), pp. 117-148

- ↑ "Friday the 13th". snopes.com. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ David Emery. "Why Friday the 13th is unlucky". urbanlegends.about.com. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Les derniers jours des Templiers". Science et Avenir: 52–61. July 2010.

- ↑ Barber, Trial of the Templars, p. 178.

- ↑ Edgeller, Johnathan (2010). Taking the Templar Habit: Rule, Initiation Ritual, and the Accusations against the Order. Texas Tech University. pp. 62–66.

- ↑ Martin, p. 118.

- ↑ Martin, p. 122.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Barber, Trial, 1978, p. 3.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Martin, p. 125.

- ↑ Martin, p. 140.

- ↑ Malcolm Barber has researched this legend and concluded that it originates from La Chronique métrique attribuée à Geffroi de Paris, ed. A. Divèrres, Strasbourg, 1956, pages 5711-5742. Geoffrey of Paris was "apparently an eye-witness, who describes Molay as showing no sign of fear and, significantly, as telling those present that God would avenge their deaths". Barber, The Trial of The Templars, page 357, footnote 110, Second edition (Cambridge University Press, 2006). ISBN 0-521-67236-8

- ↑ In The New Knighthood Barber referred to a variant of this legend, about how an unspecified Templar had appeared before and denounced Clement V and, when he was about to be executed sometime later, warned that both Pope and King would "within a year and a day be obliged to explain their crimes in the presence of God", found in the work by Ferretto of Vicenza, Historia rerum in Italia gestarum ab anno 1250 ad annum usque 1318 (Malcolm Barber, The New Knighthood, pages 314-315, Cambridge University Press, 1994). ISBN 0-521-55872-7

- ↑

"The Knights Templars". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"The Knights Templars". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - ↑ Martin, pp. 140–142.

- ↑ "Long-lost text lifts cloud from Knights Templar". msn.com. October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ Charles d' Aigrefeuille, Histoire de la ville de Montpellier, Volume 2, page 193 (Montpellier: J. Martel, 1737-1739).

- ↑ Sophia Menache, Clement V, page 218, 2002 paperback edition ISBN 0-521-59219-4 (Cambridge University Press, originally published in 1998).

- ↑ Germain-François Poullain de Saint-Foix, Oeuvres complettes de M. de Saint-Foix, Historiographe des Ordres du Roi, page 287, Volume 3 (Maestricht: Jean-Edme Dupour & Philippe Roux, Imprimeurs-Libraires, associés, 1778).

- ↑ Étienne Baluze, Vitae Paparum Avenionensis, 3 Volumes (Paris, 1693).

- ↑ Pierre Dupuy, Histoire de l'Ordre Militaire des Templiers (Foppens, Brusselles, 1751).

- ↑ "Knights Templar secrets revealed". CNN. October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ Frale, Barbara (2004). "The Chinon chart—Papal absolution to the last Templar, Master Jacques de Molay". Journal of Medieval History 30 (2): 109–134. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2004.03.004. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ↑ Burman, p. 28.

- ↑ Barber, Trial, 1978, p. 10.

- ↑ Selwood, Dominic. "The Knights Templar 1: The Knights". Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ The Rule of the Templars. p. article 17.

- ↑ Barber, New Knighthood, p. 190.

- ↑ Martin, p. 54.

- ↑

"The Knights Templars". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"The Knights Templars". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - ↑ Selwood, Dominic. "The Knights Templars 2: Sergeants, Women, Chaplains, Affiliates". Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ Read, p. 137.

- ↑ Burman, p. 43.

- ↑ Burman, pp. 30–33.

- ↑ Martin, p. 32.

- ↑ Barber, New Knighthood, p. 191.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Burman, p. 44.

- ↑ Barber, The New Knighthood, page 66: "According to William of Tyre it was under Eugenius III that the Templars received the right to wear the characteristic red cross upon their tunics, symbolising their willingness to suffer martyrdom in the defence of the Holy Land." (WT, 12.7, p. 554. James of Vitry, 'Historia Hierosolimatana', ed. J. ars, Gesta Dei per Francos, vol I(ii), Hanover, 1611, p. 1083, interprets this as a sign of martyrdom.)

- ↑ Martin, The Knights Templar, page 43: "The Pope conferred on the Templars the right to wear a red cross on their white mantles, which symbolised their willingness to suffer martyrdom in defending the Holy Land against the infidel."

- ↑ Read, The Templars, page 121: "Pope Eugenius gave them the right to wear a scarlet cross over their hearts, so that the sign would serve triumphantly as a shield and they would never turn away in the face of the infidels': the red blood of the martyr was superimposed on the white of the chaste." (Melville, La Vie des Templiers, p. 92.)

- ↑ Burman, p. 46.

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 141.

- ↑ Barber, New Knighthood, p. 193.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Picknett, Lynn and Prince, Clive (1997). The Templar Revelation. New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84891-0.

- ↑ Martin, p. 52.

- ↑ Newman, Sharan (2007). The Real History Behind the Templars. Berkeley Publishing. pp. 304–312.

- ↑ Barber, Trial, 1978, p. 4.

- ↑ Martin, p. 58.

- ↑ Barber, New Knighthood (1994), pp. 194–195

- ↑ Finlo Rohrer (October 19, 2007). "What are the Knights Templar up to now?". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ↑ The Mythology Of The Secret Societies (London: Secker and Warburg, 1972). ISBN 0-436-42030-9

- ↑ Peter Partner, The Murdered Magicians: The Templars And Their Myth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982). ISBN 0-19-215847-3

- ↑ John Walliss, Apocalyptic Trajectories: Millenarianism and Violence In The Contemporary World, page 130 (Bern: Peter Lang AG, European Academic Publishers, 2004). ISBN 3-03910-290-7

- ↑ Michael Haag, Templars: History and Myth: From Solomon's Temple To The Freemasons (Profile Books Ltd, 2009). ISBN 978-1-84668-153-0

- ↑ Knights Templar FAQ, accessed January 10, 2007.

- ↑ "Freemasonry Today periodical (Issue January 2002)". Grand Lodge Publications Ltd. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ El-Nasr, Magy Seif; Maha Al-Saati; Simon Niedenthal; David Milam. "Assassin's Creed: A Multi-Cultural Read" (PDF). pp. 6–7. Retrieved 2009-10-01. "we interviewed Jade Raymond ... Jade says ... Templar Treasure was ripe for exploring. What did the Templars find"

- ↑ Louis Charpentier, Les Mystères de la Cathédrale de Chartres (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1966), translated The Mysteries of Chartres Cathedral (London: Research Into Lost Knowledge Organisation, 1972).

- ↑ Read, p. 91.

- ↑ Read, p. 171.

- ↑ Martin, p. 139.

- ↑ Sanello, Frank (2003). The Knights Templars: God's Warriors, the Devil's Bankers. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 207–208. ISBN 0-87833-302-9.

- ↑ Barber, Trial of the Templars, 1978, p. 62.

- ↑ Martin, p. 133.

- ↑ Karen Ralls, Knights Templar Encyclopedia: The Essential Guide to the People, Places, Events and Symbols of the Order of the Temple, page 156 (The Career Press, Inc., 2007). ISBN 978-1-56414-926-8

- ↑ Barber, The New Knighthood, p. 332

- ↑ Newman, p. 383

- ↑ Barrett, Jim (Spring 1996). "Science and the Shroud: Microbiology meets archeology in a renewed quest for answers". The Mission. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Relic, Harry Gove (1996) Icon or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud ISBN 0-7503-0398-0.

Bibliography

- Isle of Avalon, Lundy. "The Rule of the Knights Templar A Powerful Champion" The Knights Templar. Mystic Realms, 2010. Web. 30 May 2010.

- Barber, Malcolm (1994). The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42041-5.

- Barber, Malcolm (1993). The Trial of the Templars (1 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45727-0.

- Barber, Malcolm (2006). The Trial of the Templars (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67236-8.

- Barber, Malcolm (1992). "Supplying the Crusader States: The Role of the Templars". In Benjamin Z. Kedar. The Horns of Hattin. Jerusalem and London. pp. 314–326.

- Barrett, Jim (1996). "Science and the Shroud: Microbiology meets archaeology in a renewed quest for answers". The Mission (University of Texas Health Science Center) (Spring). Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- Burman, Edward (1990). The Templars: Knights of God. Rochester: Destiny Books. ISBN 0-89281-221-4.

- Mario Dal Bello, Gli Ultimi Giorni dei Templari, Città Nuova, 2013, ean 9788831164511

- Frale, Barbara (2004). "The Chinon chart – Papal absolution to the last Templar, Master Jacques de Molay". Journal of Medieval History 30 (2): 109. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2004.03.004.

- Hietala, Heikki (1996). "The Knights Templar: Serving God with the Sword". Renaissance Magazine. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Marcy Marzuni (2005). Decoding the Past: The Templar Code (Video documentary). The History Channel.

- Stuart Elliott (2006). Lost Worlds: Knights Templar (Video documentary). The History Channel.

- Martin, Sean (2005). The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-645-1.

- Newman, Sharan (2007). The Real History behind the Templars. New York: Berkley Trade. ISBN 978-0-425-21533-3.

- Nicholson, Helen (2001). The Knights Templar: A New History. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-2517-5.

- Picknett, Lynn; Clive Prince (1998). The Templar Revelation. New York: Touchstone. ISBN 0-684-84891-0.

- Read, Piers (2001). The Templars. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81071-9.

- Selwood, Dominic (2002). Knights of the Cloister. Templars and Hospitallers in Central-Southern Occitania 1100-1300. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0851158285.

- Selwood, Dominic (1996). 'Quidam autem dubitaverunt: the Saint, the Sinner. and a Possible Chronology' in Autour de la Première Croisade,. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. ISBN 2859443088.

- Selwood, Dominic. “The Knights Templar 1: The Knights (2013)

- Selwood, Dominic. “The Knights Templar 2: Sergeants, Women, Chaplains, Affiliates (2013)

- Selwood, Dominic. “The Knights Templar 3: Birth of the Order (2013)

- Selwood, Dominic. “The Knights Templar 4: Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (2013)

- Théry, Julien. "A Heresy of State : Philip the Fair, the Trial of the ‘Perfidious Templars’, and the Ponticalization of the French Monarchy", Journal of Religious Medieval Cultures 39/2 (2013), p. 117-148

Further reading

- Malcolm Barber, Keith Bate. The Templars: Selected sources translated and annotated by Malcolm Barber and Keith Bate (Manchester University Press, 2002) ISBN 0-7190-5110-X

- Addison, Charles. The History of the Knights Templar (1842)

- d'Albon, André. Cartulaire général de l'ordre du Temple: 1119?–1150 (1913–1922) (at Gallica)

- Barber, Malcolm (2006-04-20). "The Knights Templar – Who were they? And why do we care?". Slate Magazine. ;

- Brighton, Simon (2006-06-15). In Search of the Knights Templar: A Guide to the Sites in Britain. London, England: Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 0-297-84433-4.

- Butler, Alan; Stephen Dafoe (1998). The Warriors and the Bankers: A History of the Knights Templar from 1307 to the present. Belleville: Templar Books. ISBN 0-9683567-2-9.

- Frale, Barbara (2009). The Templars: The secret history revealed. Dunboyne: Maverick House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-905379-60-6.

- Gordon, Franck (2012). The Templar Code: French title: Le Code Templier. Paris, France: Yvelinedition. ISBN 978-2-84668-253-4.

- Haag, Michael (2012). The Tragedy of the Templars. London: Profile Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84668-450-0.

- Haag, Michael (2008). The Templars: History and Myth. London: Profile Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84668-148-6.

- Hodapp, Christopher; Alice Von Kannon (2007). The Templar Code For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0-470-12765-1.

- Levaye, Patrick. Géopolitique du Catholicisme (Éditions Ellipses, 2007) ISBN 2-7298-3523-7

- Partner, Peter (1990). The Knights Templar & Their Myth. Rochester: Destiny Books. ISBN 0-89281-273-7.

- Ralls, Karen (2003). The Templars and the Grail. Wheaton: Quest Books. ISBN 0-8356-0807-7.

- Smart, George (2005). The Knights Templar Chronology. Bloomington: Authorhouse. ISBN 1-4184-9889-0.

- Upton-Ward, Judith Mary (1992). The Rule of the Templars: The French Text of the Rule of the Order of the Knights Templar. Ipswich: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-315-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Knights Templar. |