Kirkcudbrightshire

| Kirkcudbrightshire | |

|---|---|

| County (until circa 1890) | |

| |

| Country | Scotland |

| County town | Kirkcudbright |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,323 km2 (897 sq mi) |

| Ranked 10th | |

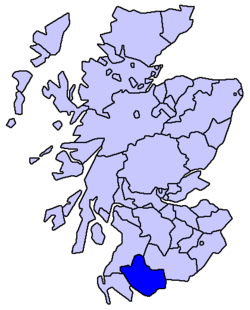

| Chapman code | KKD |

Kirkcudbrightshire (/kərˈkuːbriːʃər/ kirr-KOO-bree-shər), or the County of Kirkcudbright or the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Galloway region of south-western Scotland. For local government purposes, it forms part of the wider Dumfries and Galloway council area of which it forms a committee area under the name of the Stewartry.

The county is occasionally referred to as East Galloway,[2] forming the larger Galloway region with Wigtownshire. It is bounded on the north and north-west by Ayrshire, on the west and south-west by Wigtownshire, on the south and south-east by the Irish Sea and the Solway Firth, and on the east and north-east by Dumfriesshire. It included the small islands of Hestan and Little Ross.

It maintains a strong regional and distinct political identity. It formed a district in the Dumfries and Galloway region and today the Stewarty is an area committee represented by eight councillors. Local administration of the area today is overseen by a Stewartry Area Manager, based in the county town of Kirkcudbright. The current Lord Lieutenant of Kirkcudbright, the Crown's representative in the area, is Lt Col Sir Malcolm Ross.

Early History

The country west of the Nith was originally peopled by a tribe of Celts called Novantae, who long retained their independence.

After Agricola's invasion in 79 AD the country nominally formed part of the Roman province of Britannia, but the evidence is against there ever having been a prolonged effective Roman occupation. Details of the Roman Temporary Marching Camp at Shawhead, Irongray Parish, is at [3]

After the retreat of the Romans, the fate of the Novantae is unknown but by the 6th century Galloway was part of the Brythonic kingdom of Rheged.

By the 7th century much of Galloway became part of the English kingdom of Northumbria.

11th 12th and 13th centuries

During the next two hundred years the country had no rest from Danish and Saxon incursions and the continual lawlessness of the Scandinavian rovers.[citation needed]

When Malcolm Canmore defeated and slew Macbeth in 1057 he married the dead king's relative Ingibiorg, a Pictish princess, (the view that there were Picts in Galloway in historical times can not be wholly rejected) an event which marked the beginning of the decay of Norse influence. The Galloway chiefs hesitated for a time whether to throw in their lot with the Northumbrians or with Malcolm; but language, race and the situation of their country at length induced them to become lieges of the Scottish king.[citation needed]

By the close of the 11th century the boundary between England and Scotland was roughly delimited on what became permanent lines. The feudal system ultimately destroyed the power of the Galloway chiefs, who resisted the innovation to the last.

Several of the lords or "kings" of Galloway, a line said to have been founded by Fergus, the greatest of them all, asserted in vain their independence of the Scottish crown;[citation needed] and in 1234 the line became extinct in the male branch on the death of Fergus's great-grandson Alan.

One of Alan's daughters, Dervorguilla, had married John, 5th feudal lord Balliol, he and Dervorguilla being parents of King John I of Scotland (1292–1296), and the people, out of affection for Alan's daughter, were lukewarm in support of Robert the Bruce.[citation needed]

14th and 15th centuries

In 1308 the district was cleared of the English and brought under allegiance to the king, when the lordship of Galloway was given to Edward Bruce.

Later in the 14th century Galloway espoused the cause of Edward Baliol, who surrendered several counties, including Kirkcudbright, to Edward III of England.

In 1372 Archibald the Grim, a natural son of Sir James Douglas "the Good", became Lord of Galloway and received in perpetual fee the Crown lands between the Nith and the Cree. He appointed a steward to collect his revenues and administer justice, and there thus arose the designation of the "Stewartry of Kirkcudbright".[4]

The high-handed rule of the Douglases created general discontent, and when their treason became apparent their territory was overrun by the king's men in 1455; Douglas was attainted, and his honours and estates were forfeited.

In that year the great stronghold of the Thrieve,[5] the most important fortress in Galloway, which Archibald the Grim had built on the Dee immediately to the west of the modern town of Castle Douglas, was reduced and converted into a royal keep. (It was dismantled in 1640 by order of the Estates in consequence of the hostility of its keeper, Lord Nithsdale, to the Covenant.) The famous cannon Mons Meg, now in Edinburgh Castle, is said, apparently on limited evidence, to have been constructed in order to aid James III in this siege.

16th and 17th centuries

As the Douglases went down the Maxwells rose, and the debatable land on the south-east of Dumfriesshire was for generations the scene of strife and raid, not only between the two nations but also among the leading families, of whom the Maxwells, Johnstones and Armstrongs were always conspicuous. After the battle of Solway Moss (1542) the shires of Kirkcudbright and Dumfries fell under English rule for a short period. The treaty of Norham (24 March 1550) established a truce between the nations for ten years; and in 1552, the Wardens of the Marches consenting, the debatable land ceased to be matter for debate, the parish of Canonbie being annexed to Dumfriesshire, that of Kirkandrews to Cumberland.

Though at the Reformation the Stewartry became fervent in its Protestantism, it was to Galloway, through the influence of the great landowners and the attachment of the people to them, that Mary, Queen of Scots, owed her warmest adherents, and it was from the coast of Kirkcudbright that she made her luckless voyage to England.

Even when the crowns of Scotland and England were united in 1603 turbulence continued; for trouble arose over the attempt to establish episcopacy, and nowhere were the Covenanters more cruelly persecuted than in Galloway.

18th century

McCulloch and Gordon families were of Cardoness Castle, Anwoth Parish and Rev. Rutheford was minister of Anwoth.

After the union (1707) things mended slowly but surely, curious evidence of growing commercial prosperity being the enormous extent to which smuggling was carried on. No coast could serve the "free traders" better than the shores of Kirkcudbright, and the contraband trade flourished until the 19th century. The Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745 elicited small sympathy from the inhabitants of the shire.

Geography

The north-western part of the former county is rugged, wild and desolate. In this quarter the principal mountains are Merrick 843 m (2764 ft), the highest in the south of Scotland, and the group of the Rhinns of Kells, the chief peaks of which are Corserine 814 m (2669 ft), Carlins Cairn 807 m (2650 ft), Meikle Millyea 746 m (2446 ft) and Millfire 716 m (2350 ft). Towards the south-west the chief eminences are Lamachan Hill 717 (2350 ft), Larg 676 m (2216 ft), and the bold mass of Cairnsmore of Fleet 711 m (2331 ft). In the south-east the only imposing height is Criffel 569 m (1868 ft). In the north rises the majestic hill of Cairnsmore of Carsphairn 797 m (2614 ft), and close to the Ayrshire border is the Windy Standard 698 m (2290 ft). The southern section of the shire is mostly level or undulating, but characterised by picturesque scenery.

The shore is generally bold and rocky, indented by numerous estuaries forming natural harbours, which however are of little use for commerce owing to the shallowness of the sea. Large stretches of sand are exposed in the Solway at low water and the rapid flow of the tide has often occasioned loss of life.

There are many "burns" and "waters", but their length seldom exceeds 7 or 8 miles (13 km). Among the longer rivers are the Cree, which rises in Loch Moan and reaches the sea near Creetown after a course of about 30 miles (48 km), during which it forms the boundary, at first of Ayrshire and then of Wigtownshire; the Dee or Black Water of Dee (so named from the peat by which it is coloured), which rises in Loch Dee and after a course mainly S.E. and finally S., enters the sea at St Mary's Isle below Kirkcudbright, its length being nearly 36 miles (58 km); the Urr, rising in Loch Urr on the Dumfriesshire border, falls into the sea a few miles south of Dalbeattie 27 miles (43 km) from its source; the Ken, rising on the confines of Ayrshire, flows mainly in a southerly direction and joins the Dee at the southern end of Loch Ken after a course of 24 miles (39 km) through lovely scenery; and the Deugh which, rising on the northern flank of the Windy Standard, pursues an extraordinarily winding course of 20 miles (32 km) before reaching the Ken. The Nith, during the last few miles of its flow, forms the boundary with Dumfriesshire, to which county it almost wholly belongs.

The lochs and mountain tarns are many and well-distributed; but except for Loch Ken, which is about 6 miles (10 km) long by half a mile (1 km) wide, few of them attain noteworthy dimensions. There are several passes in the hill regions, but the only well-known glen is Glen Trool, not far from the district of Carrick in Ayrshire, the fame of which rests partly on the romantic character of its scenery, which is very wild around Loch Trool, and more especially on its associations with Robert the Bruce. It was here that when most closely beset by his enemies, who had tracked him to his fastness by sleuth hounds, Bruce with the aid of a few faithful followers won a surprise victory over the English in 1307 which proved the turning-point of his fortunes.

Geology

Silurian and Ordovician rocks are the most important in this county; they are thrown into oft-repeated folds with their axes lying in a north-east–south-west direction. The Ordovician rocks are graptolitic black shales and grits of Llandeilo and Caradoc age. They occupy all the northern part of the county north-west of a line which runs some 3 m. north of New Galloway and just south of the Rinns of Kells. South-east of this line graptolitic Silurian shales of Llandovery age prevail; they are found around Dalry, Creetown, New Galloway, Castle Douglas and Kirkcudbright.

Overlying the Llandovery beds on the south coast are strips of Wenlock rocks; they extend from Bridgehouse Bay to Auchinleck and are well exposed in Kirkcudbright Bay, and they can be traced farther round the coast between the granite and the younger rocks. Carboniferous rocks appear in small faulted tracts, unconformable on the Silurian, on the shores of the Solway Firth. They are best developed about Kirkbean, where they include a basal red breccia followed by conglomerates, grits and cement stones of Calciferous Sandstone age.

Brick-red sandstones of Permian age just come within the county on the W. side of the Nith at Dumfries. Volcanic necks occur in the Permian and basalt dikes penetrate the Silurian at Borgue, Kirkandrews, etc.

Most of the highest ground is formed by the masses of granite which have been intruded into the Ordovician and Silurian rocks; the Criffel mass lies about Dalbeattie and Bengairn, another mass extends east and west between the Cairnsmore of Fleet and Loch Ken, another lies north-west and south-east between Loch Doon and Loch Dee and a small mass forms the Cairnsmore of Carsphairn.

Glacial deposits occupy much of the low ground; the ice, having travelled in a southerly or south-easterly direction, has left abundant striae on the higher ground to indicate its course. Radiation of the ice streams took place from the heights of Merrick, Kells, etc.; local moraines are found near Carsphairn and in the Deagh and Minnoch valleys. Glacial drumlins of boulder clay lie in the vales of the Dee, Cree and Urr.

Climate and agriculture

The climate and soil suit grass and green crops rather than grain. The annual rainfall averages 45.7inches (1.16 m). The mean temperature for the year is 9 °C (48 °F); for January 4 °C (39 °F); for July 15 °C (59 °F). The major part of the land is either waste or poor pasture.

List of parishes

The Stewartry is composed of the following 28 civil parishes.[6]

- Anwoth

- Balmaclellan

- Balmaghie

- Borgue

- Buittle

- Carsphairn

- Colvend and Southwick[7]

- Crossmichael

- Dalry

- Girthon, see also Gatehouse of Fleet and Cally Palace [8][9][10]

- Irongray [11][12][13] John Welsh of Irongray

- Kells, Dumfries and Galloway[14]

- Kelton Sir William Douglas, 1st Baronet [15][16]

- Kirkbean

- Kirkcudbright

- Kirkgunzeon [17][18]

- Kirkmabreck [19][20]

- Kirkpatrick Durham

- Lochrutton [21][22]

- Minnigaff

- New Abbey

- Parton

- Rerrick [23][24] Dundrennan Abbey

- Terregles

- Tongland

- Troqueer

- Twynholm

- Urr

Towns and villages

In order of size the chief towns are:-

Other notable towns and villages include:-

- Creetown

- St. John's Town of Dalry

- New Galloway

- Carsphairn

- Corsock

- Auchencairn

- Palnackie

- Haugh of Urr

- New Abbey

- Kirkpatrick Durham

- Laurieston

In 1930 Maxwelltown or the eastern-side over the River was transferred to Dumfriesshire. The eastern-side is now a suburb of the town of Dumfries.

Gallery

-

Garlies Castle. photo by Mark McKie

-

Wreaths Tower, Kirkbean.

-

Orchardtown Tower, Buittle.

-

Kenmure Castle, Kells.

-

Threave Castle. photo by Alison Stamp

-

Kenmure Castle, Kells parish. photo by Chris Newman

-

Cardoness Castle. photo by Otter

-

McLellan's Castle, Kirkcudbright. photo by Colin Smith

-

Lochinvar Castle site.

Notable Inhabitants

- Formula 1 driver David Coulthard was born in Twynholm Kirkcudbrightshire.

- John Paul Jones, Scottish, American, and Russian naval commander

References and Bibliography

- ↑ Map of Parishes in the Counties of Wigtown & Kircudbright, ScotlandsFamily

- ↑ The New Statistical Account of Scotland (1834)

- ↑ http://www.roman-britain.org/places/shawhead.htm

- ↑ "Visit Kirkcudbright - Historical Sites". Kirkcudbright.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Threave_Castle

- ↑ Author: stephenclancy (2012-05-22). "The Parishes". Stewartrykirks.org.uk. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ "The Parish of Colvend". Kirkcudbright.co. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ Civil Parish of Girthon map. http://www.scottish-places.info/parishes/parmap1044.html

- ↑ A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. by Samuel Lewis. Vol.I. Second Edition. Pub. 1851. (copyright expired) pp.490-491 http://archive.org/stream/topographicaldic01lewi#page/490/mode/2up

- ↑ "Parish of Girthon - History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway". Kirkcudbright.co. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ Scotlands Places. http://www.scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/search/?action=do_search&p_type=PARISH&p_name=kirkpatrick_irongray&id=1014&p_county=kirkcudbrightshire

- ↑ A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. by Samuel Lewis. Vol.II. Second Edition. Pub. 1851. p.125 http://archive.org/stream/topographicaldic02lewi#page/125/mode/1up

- ↑ Statistical Account.published 1792 http://www.archive.org/stream/statisticalacco09sincgoog#page/n533/mode/2up

- ↑ "Parish of Kells Map". Scottish-places.info. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ Caledonia. Vol.III. by George Chalmers, P.R.S. and S.A.. published 1824. p.314 Parish of Kelton. http://archive.org/stream/caledoniaoraccou03chal#page/314/mode/1up

- ↑ "The Parish of Kelton". Kirkcudbright.co. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. by Samuel Lewis. Vol.II. Second Edition. Pub. 1851. pp.106-107 http://archive.org/stream/topographicaldic02lewi#page/106/mode/2up

- ↑ "The Parish of Kirkgunzeon". Kirkcudbright.co. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. by Samuel Lewis. Vol.II. Second Edition. Pub. 1851. pp.112-113 http://archive.org/stream/topographicaldic02lewi#page/112/mode/2up

- ↑ "The Parish of Kirkmabreck". Kirkcudbright.co. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. by Samuel Lewis. Vol.II. Second Edition. Pub. 1851. pp.200-201 http://archive.org/stream/topographicaldic02lewi#page/200/mode/2up

- ↑ "The Parish of Lochrutton". Kirkcudbright.co. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. by Samuel Lewis. Vol.II. Second Edition. Pub. 1851. pp.415-416 http://archive.org/stream/topographicaldic02lewi#page/414/mode/2up

- ↑ "The Parish of Rerrick". Kirkyards.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- Sir Herbert Maxwell, History of Dumfries and Galloway (Edinburgh, 1896)

- Rev. Andrew Symson, A Large Description of Galloway (1684; new ed., 1823) http://books.google.com.au/books?id=4mYLAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=Dalry&f=false

- Thomas Murray, The Literary History of Galloway (1822)

- Rev. William Mackenzie, History of Galloway (1841)

- P. H. McKerlie, History of the Lands and their Owners in Galloway (Edinburgh, 1870–1879)

- Galloway Ancient and Modern (Edinburgh, 1891)

- J. A. H. Murray, Dialect of the Southern Counties of Scotland (London, 1873).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kirkcudbrightshire. |

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

| |||||||||||||

Coordinates: 55°00′N 4°00′W / 55.000°N 4.000°W