Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia[nb 1] was a state in Europe from the early 14th century until the mid-19th. It was the predecessor state of today's Italy.[1] A small state with weak institutions when it was acquired by the House of Savoy in 1720, the Savoyards united their insular and continental domains and built Sardinia—often called Piedmont-Sardinia in this period—into one of the great powers by the time of the Crimean War (1853–56).[2] Its final capital was Turin, the centre of Savoyard power since the Middle Ages.

The kingdom initially consisted of the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, sovereignty over both of which was claimed by the Papacy, which granted them as a fief, the regnum Sardiniae et Corsicae ("kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica"), to King James II of Aragon in 1297. Beginning in 1324, James and his successors conquered the island of Sardinia and established de facto their de jure authority. In 1420 the last competing claim to the island was bought out. After the union of the crown of Aragon with that of Castile, Sardinia became a part of the burgeoning Spanish Empire. In 1720 it was ceded by the Habsburg and Bourbon claimants to the Spanish throne to the Duke Victor Amadeus II of Savoy. The kingdom of Sardinia came progressively to be identified with the entire domain ruled by the House of Savoy, which included, besides Savoy and Aosta, dynastic possessions since the 11th century, the Principality of Piedmont (a possession built up in the 13th century) and the County of Nice (a possession since 1388). While the traditional capital of the island of Sardinia and seat of its viceroys was Cagliari, the Piedmontese city of Turin was the de facto capital of the House of Savoy.

When the mainland domains of the House of Savoy were occupied and eventually annexed by the Napoleonic France, the King of Sardinia made his permanent residence on the island for the first time in its history. The Congress of Vienna (1814–15), which restructured Europe in light of Napoleon's defeat, returned to Savoy its mainland possessions and augmented them with Liguria, taken from Republic of Genoa. In 1847–48, in a "perfect fusion", the various Savoyard states were unified under one legal system, with its capital in Turin, and granted a constitution, the Statuto Albertino. There followed the annexation of Lombardy (1859), the central Italian states and the Two Sicilies (1860), Venetia (1866) and the Papal States (1870). On 17 March 1861, to more accurately reflect its new geographic extent, the Kingdom of Sardinia changed its name to the Kingdom of Italy, and its capital was eventually moved first to Florence then to Rome in 1870.

Early history

In 238 BC Sardinia became, with Corsica, a province of the Roman Empire. The Romans ruled the island until the middle of the 5th century, when it was occupied by the Vandals, who had also settled in north Africa. In 534 AD it was reconquered by the Romans, but now, they were from the Eastern Roman Empire, from Byzantium. It remained a Byzantine province until the Arab conquest of Sicily, in the 9th century. After that, communications with Constantinople became very difficult, so the powerful or one of the powerful families of the island were forced to take the power.

Sardinia faced Arab attempts to sack and conquer the island almost without help, but it still organized itself according to the imperial ideology of Byzantium. The state was not a personal property of the ruler and of his family, as in western Europe, but was a separate institution, as it was during the Roman and Byzantine Empires, a monarchical republic.

Starting from 705–706, the Saracens from North Africa (recently conquered by the Arab armies) harassed the population of the coastal cities. News about the political situation of Sardinia in the following centuries are scarce. Due to Saracen attacks, in the 9th century Tharros was abandoned in favor of Oristano, after more than 1800 years of occupation; Caralis, Porto Torres and numerous other coastal centres suffered the same fate. There are news of another massive Saracen sea attack in 1015–16 from Balearics, led by Mujāhid al-ʿĀmirī (Latinized in Museto), the saracen's attempt of invasion of the island was stopped by the Byzantine-Sardinian kingdom or Judicatus with the support of the Fleets of Maritime Republics of Pisa and Genoa, free cities of the Holy Roman Empire. Pope Benedict VIII as well asked the aid of the maritime republics of Pisa and Genoa in the struggle against the Arabs.[3]

After the Great Schism Rome made many efforts to re-Latinize the Sardinian church, politics and society, and finally unify again the island under only one Catholic ruler, as it was for all southern Italy, where Byzantines were pushed away by Catholic Normans. Even the title of Judices was a Byzantine reminder of the Greek church and state, in times of harsh relations between eastern and western churches (Massacre of the Latins, 1182, Siege of Constantinople (1204), Recapture of Constantinople, 1261). Before the Kingdom of Sardinia et Corsica so, the Archons (ἄρχοντες) or in Latin Judices,[4][5] that reigned in the island from the 9th or 10th century until the beginning of the 11th, can be considered as real kings of all Sardinia (Κύριε βοήθε ιοῦ δού λού σου Tουρκοτουρίου ἅρχωντοσ Σαρδινίας καί τής δού ληςσου Γετιτ[6]),[7][8] even though nominal vassals of the Byzantine emperors, but the rulers in fact of the island. Of this sovereigns we have only received two names: Turcoturiu and Salusiu (Tουρκοτουριου βασιλικου προτοσπαθαριου [9] και Σαλουσιου των ευγενεστατων άρχωντων),[10][11] that ruled probably in the 10th century. The Archons wrote still in Greek or Latin, and one of the first document of the Judex of Cagliari, their direct successor, was written in romance Sardinian language but with Greek alphabet.

The realm was divided into four small kingdoms, the Judicati, perfectly organized as the previous, but now under the influence of the Pope and that of Holy Roman Empire and its Frankish-Roman political ideology. That was the cause of the long war between the Judices who thought they were Kings and Kings that only believed in fighting against rebellious nobles.[12] Byzantine political doctrine died permanently with the last Judicatus, in 1410, when the new Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica defeated the Arborea Judicatus in a battle in Sanluri and its sovereign rights were sold by the last Judex. It was only a few decades before the conquest of Constantinople by the Muslim Turks, and the discovery of the new world. It is claimed that, excluding the Republic of Venice, Sardinia was the last and direct institutional and ideological country of roman ancestry in western Europe by 1410.[citation needed]

Later, the title of King of Sardinia was then granted by the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire to Barisone II of Arborea[13] and Enzio of Sardinia. The first could not reunify the island under his rule, despite years of wars against the other Sardinian judices and finally gave it up in a peace treaty with them in 1172.[14] The second did not have the opportunity. Invested with the title from his father, Emperor Frederick II in 1239, he was soon recalled by the parent and appointed Imperial Vicar for Italy. He ended his days, without direct recognized heirs, after a detention of 23 years in a prison in Bologna in 1272.

The Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica (later, just the "Kingdom of Sardinia" from 1460[15]) was a state whose king was the King of Aragon, who conquered it in 1324 and directly ruled it until 1460. In that year it was incorporated into a sort of confederation of States, each one of them with its own institutions, called the Crown of Aragon, and united only in the person of the same king. The Crown of Aragon was made by a council of representatives of the various States and grew in importance for the main purpose of separating the legacy of Ferdinand II of Aragon from that of Isabella I of Castile when they married in 1469. The idea of the kingdom was created in 1297 by Pope Boniface VIII, as a hypothetical entity created for James II of Aragon under a secret clause in the Treaty of Anagni, as an inducement to join in the effort to restore Sicily, then under the rule of James's brother Frederick III of Sicily, to the Angevin dynasty over the oppositions of the Sicilians. The two islands proposed for this new kingdom were occupied by other states and fiefs at the time. In Sardinia, three of the four states that had succeeded Byzantine imperial rule in the 9th century had passed through marriage and partition under the direct or indirect control of Pisa and Genoa in the 40 years preceding the Anagni treaty. Genoa had also ruled Corsica since conquering the island nearly two centuries before (c. 1133).

There were other reasons beside this papal decision: it was the final successful result of the long fight against the Ghibelline (pro-imperial) city of Pisa and the Holy Roman Empire itself. Furthermore, now, Sardinia would be under the control of the very Catholic Kings of Aragon, and the last result of rapprochement of the island to Rome. The Sardinian church had never been under the control of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, it was an autonomous province loyal to Rome but was very influenced by Byzantine liturgy and culture.

Foundation of the Kingdom of Sardinia

In 1297, Pope Boniface VIII, intervening between the Houses of Anjou and Aragon, established on paper a Regnum Sardiniae et Corsicae that would be a fief of the Papacy. Then, ignoring the indigenous states which already existed, the Pope offered his newly invented fief to James II of Aragon, promising him papal support should he wish to conquer Pisan Sardinia in exchange for Sicily. In 1323 James II formed an alliance with Hugh II of Arborea and, following a military campaign which lasted a year or so, occupied the Pisan territories of Cagliari and Gallura along with the city of Sassari, claiming the territory as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica. In 1353 Aragon made war on Arborea, then fought with its leader Marianus IV of Arborea, of the Cappai de Bas family, but did not reduce the last of the giudicati (indigenous kingdoms of Sardinia) until 1420. The Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica retained its separate character as part of the Crown of Aragon and was not merely incorporated into the Kingdom of Aragon. At the time of his struggles with Arborea, Peter IV of Aragon granted an autonomous legislature to the Kingdom and its legal traditions. The Kingdom was governed in the king's name by a Viceroy.

In 1420, Alfonso V of Aragon, king of Sicily and heir to Aragon, bought the remaining territories for 100,000 gold florins of the Giudicato of Arborea in the 1420 from the last giudice William III of Narbonne and the "Kingdom of Sardinia" extended throughout the island, except for the city of Castelsardo (at that time called Casteldoria or Castelgenovese) that was stolen from the Doria in 1448, and renamed Castillo Aragonés (Aragonese Caste).

Corsica, which had never been conquered, was dropped from the formal title and Sardinia passed with the Crown of Aragon to a united Spain. The defeat of the local kingdoms, communes and signorie, the firm Aragonese (later Spanish) rule, with the introduction of a sterile feudalism, as well as the discovery of the Americas, provoked an unstoppable decline of Kingdom of Sardinia. A short period of uprisings occurred under the local noble Leonardo de Alagon, marquess of Oristano, defended his territories against the Viceroy Nicolò Carroz, and who managed to defeat the viceroy's army in the 1470s but was later crushed at the Battle of Macomer in 1478, ending any further revolts in the island. The unceasing attacks from North African pirates and a series of plagues (from 1582, 1652 and 1655) further worsened the situation.

Aragonese Conquest of Sardinia

Although the "Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica" could be said to have started as a questionable and extraordinary de jure state in 1297, its de facto existence began in 1324 when, called by their allies of the Giudicato di Arborea in the course of war with the Republic of Pisa, James II seized the Pisan territories in the former states of Cagliari and Gallura and asserted his papally approved title. In 1347 CE Aragon made war on some landlords, Doria House and Malaspina House, who were citizen of the Republic of Genoa, which so controlled most of the lands of the former Logudoro state in north-western Sardinia, including the city of Alghero and the semiautonomous Republic of Sassari, and added them to its direct domains.

The Giudicato of Arborea, the only Sardinian state that remained independent of foreign domination, proved far more difficult to subdue (Giudicato is the Italian word equivalent in contemporary usage to "kingdom" or "duchy."). Threatened by the Aragonese claims of suzerainty and consolidation of the rest of the island, Arborea continued the conquest of the remaining Sardinian territories beginning in 1353. In 1368 an Aborea offensive succeeded in nearly driving the Aragonese from the island, reducing the "Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica" to just the port cities of Cagliari and Alghero, and incorporating everything else into their own kingdom. A peace treaty returned the Aragonese their previous possessions in 1388, but tensions continued and 1382 CE the Arborean army led by Brancaleone Doria again swept the most of the island into Arborean rule. This situation lasted until the 1409 when the army of the giudicato of Arborea suffered a heavy defeat the Aragonese army in the Battle of Sanluri. After the sale of the remaining territories for 100,000 gold florins of the Giudicato of Arborea in the 1420, the "Kingdom of Sardinia" extended throughout the island, excepet for the city of Castelsardo (at that time called Casteldoria or Castelgenovese) that was stolen from the Doria in 1448. The subduing of Sardinia having taken a century, Corsica, which had not been wrested from the Genoese, was dropped from the formal title of the Kingdom.

Early history of Piedmont

Piedmont was inhabited in early historic times by Celtic-Ligurian tribes such as the Taurini and the Salassi. They later submitted to the Romans (c. 220 BC), who founded several colonies there including Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) and Eporedia (Ivrea). After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the region was repeatedly invaded by the Burgundians, the Goths (5th century), Byzantines, Lombards (6th century), Franks (773). In the 9th–10th centuries there were further incursions by the Magyars and Saracens[citation needed]. At the time Piedmont, as part of the Kingdom of Italy within the Holy Roman Empire, was subdivided into several marks and counties.

In 1046, Oddo of Savoy added Piedmont to their main segment of Savoy, with a capital at Chambéry (now in France). Other areas remained independent, such as the powerful communes of Asti and Alessandria and the marquisates of Saluzzo and Montferrat. The County of Savoy was elevated to a duchy in 1416, and Duke Emanuele Filiberto moved the seat to Turin in 1563.

Exchange of Sardinia for Sicily

The Spanish domination of Sardinia ended at the beginning of the 18th century, as a result of War of the Spanish succession. By the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, Spain's European empire was divided: Savoy received Sicily and parts of the Duchy of Milan, while Charles VI (the Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria), received the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, Sardinia, and the bulk of the Duchy of Milan. During the War of the Quadruple Alliance, Victor Amadeus II, duke of Savoy and sovereign of Piedmont, had to agree to yield Sicily to the Austrian Habsburgs and receive Sardinia in exchange. The exchange was formally ratified in the Treaty of The Hague of 17 February 1720. Because the kingdom of Sardinia had existed since the 14th century, the exchange allowed Victor Amadeus to retain the title of king in spite of the loss of Sicily.

Victor Amadeus initially resisted the exchange, and until 1723 continued to style himself King of Sicily rather than King of Sardinia. The state took the official title of Kingdom of Sardinia, Cyprus and Jerusalem, as the house of Savoy still claimed the thrones of Cyprus and Jerusalem, although both had long been under Ottoman rule.

In 1767–1769, Charles Emmanuel III conquered the Maddalena archipelago in the Strait of Bonifacio from the Republic of Genoa, who ruled it with the island of Corsica, and since then the archipelago is still part of the Sardinian region.

Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna

In 1792, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the other states of the Savoy Crown joined the First Coalition against the French First Republic, but was beaten in 1796 by Napoleon and forced to conclude the disadvantageous Treaty of Paris (1796), giving the French army free passage through Piedmont. On 6 December 1798 Joubert occupied Turin and forced Charles Emmanuel IV to abdicate and leave for the island of Sardinia. The provisionary government voted to unite Piedmont with France. In 1799 the Austro-Russians briefly occupied the city, but with the Battle of Marengo (1800), the French regained control. The island of Sardinia stayed out of the reach of the French for the rest of the war.

In 1814, the Crown of Savoy enlarged its territories with the addition of the former Republic of Genoa, now a duchy, and it served as a buffer state against France. This was confirmed by the Congress of Vienna. In the reaction after Napoleon, the country was ruled by conservative monarchs: Victor Emmanuel I (1802–21), Charles Felix (1821–31) and Charles Albert (1831–49), who fought at the head of a contingent of his own troops at the Battle of Trocadero, which set the reactionary Ferdinand VII on the Spanish throne. Victor Emanuel I disbanded the entire Code Napoléon and returned the lands and power to the nobility and the Church. This reactionary policy went as far as discouraging the use of roads built by the French. These changes typified Piedmont. The Kingdom of Sardinia industrialized from 1830 onward. A constitution, the Statuto Albertino, was enacted in the year of revolutions, 1848, under liberal pressure: the kingdom, that, until that moment was strictly confined to island, annexed all the other states of the Savoy house but its institutions were deeply transformed: it became a constitutional and very centralized monarchy as the French model; and under the same pressure Charles Albert declared war on Austria. After initial success the war took a turn for the worse and Charles Albert was defeated by Marshal Radetzky at Custozza.

Italian unification

Like all of Italy, the Kingdom of Sardinia was troubled with political instability, under alternating governments. After a very short and disastrous renewal of the war with Austria in 1849, Charles Albert abdicated on 23 March 1849, in favour of his son Victor Emmanuel II.

In 1852, a liberal ministry under Count Camillo Benso di Cavour was installed, and the Kingdom of Sardinia became the engine driving the Italian Unification. The Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) took part in the Crimean War, allied with the Ottoman Empire, Britain, and France, and fighting against Russia.

In 1859, France sided with the Kingdom of Sardinia in a war against Austria, the Austro-Sardinian War. Napoleon III didn't keep his promises to Cavour to fight until all of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia had been conquered. Following the bloody battles of Magenta and Solferino, both French victories, Napoleon thought the war too costly to continue and made a separate peace behind Cavour's back in which only Lombardy would be ceded. Due to the Austrian government's refusal to cede any lands to the Kingdom of Sardinia, they agreed to cede Lombardy to Napoleon who in turn then ceded the territory to the Kingdom of Sardinia to avoid 'embarrassing' the defeated Austrians. Cavour angrily resigned from office when it became clear that Victor Emmanuel would accept the deal.

Garibaldi and the Thousand

On 5 March 1860, Parma, Tuscany, Modena, and Romagna voted in referenda to join the Kingdom of Sardinia. This alarmed Napoleon who feared a strong Savoyard state on his southeastern border and he insisted that if the Kingdom of Sardinia were to keep the new acquisitions they would have to cede Savoy and Nice to France. This was done after referenda showed over 99.5% majorities in both areas in favour of joining France.

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi started his campaign to conquer southern Italy in the name of the Kingdom of Sardinia. He quickly toppled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and marched to Gaeta. Cavour was actually the most satisfied with the unification while Garibaldi wanted to conquer Rome. Garibaldi was too revolutionary for the king and his prime minister.

Towards the Kingdom of Italy

On 17 March 1861, law no. 4671 of the Sardinian Parliament proclaimed the Kingdom of Italy, so ratifying the annexations of all other Italian states to Kingdom of Sardinia. The institutions and laws of the Kingdom were quickly extended to all Italy, abolishing the administrations of the other regions. Piedmont would become the most dominant and wealthiest region in Italy and the capital of Piedmont, Turin, would remain the Italian capital until 1865 when the capital was moved to Florence; but in contrast, many revolts exploded through the peninsula, especially in Southern Italy. The House of Savoy would rule Italy until 1946 when Italy was declared a republic by referendum.

Currency

The currency in use in the mainland domains of the Savoyards was Piedmontese scudo. During the Napoleonic era, it was replaced in general circulation by the French franc. In 1816, after regaining their Piedmontese dominions, the scudo was replaced by the Sardinian lira, which also replaced the Sardinian scudo, the coins that had been in use on the island throughout the period, in 1821.

Flags, Royal standards and coats of arms

When the Duchy of Savoy acquired the Kingdom of Sicily in 1713 and the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1723, the Flag of Savoy became the flag of a naval power. This posed the problem that the same flag was already in used by the Knights of Malta. Because of this, the Savoyards modified their flag for use as a naval ensign in various ways, adding the letters FERT in the four cantons, or adding a blue border, or using a blue flag with the Savoy cross in one canton.

Eventually, king Charles Albert adopted the "revolutionary" Italian tricolour, surmonted by the Savoyard shield, as his flag. This flag became the flag of Kingdom of Italy, and the tricolore without the Savoyard inescutcheon remains the flag of Italy.

-

Flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1568

-

Imperial Eagle of Roman Holy Emperor Charles V with the four Moors of the Kingdom of Sardinia

-

Coat of arms of Savoy House Kings of Sardinia

-

Royal Standard of the Savoyard kings of Sardinia of Savoy dynasty, 1720–1848

-

Variant flag used as naval ensign in the late 18th century[citation needed]

-

Variant flag used as naval ensign in the late 18th or early 19th century[citation needed]

-

.svg.png)

Flag of Kingdom of Sardinia 1848–1861, the Italian tricolore with the coat of arms of Savoy as an inescutcheon

Maps

Territorial evolution of the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1324 to 1720

-

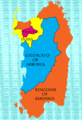

The political situation in Sardinia after 1324 when the Aragonese conquered the pisan territories of Sardinia who included the defunted Giudicato of Cagliari and Gallura.

-

The Kingdom of Sardinia from 1368 to 1388 and 1392 to 1409, after the wars with Arborea, comprehended only the cities of Cagliari and Alghero.

-

The Kingdom of Sardinia from 1410 to 1420, after the defeat of the Arborean giudicate in the battle of Sanluri (1409)

-

The Kingdom of Sardinia from 1448 to 1720, except for the Maddalena archipelago, which was conquered in 1767–69

Territorial evolution of Italy from 1796 to 1860

-

1796:Kingdom of SardiniaDuchy of Modena

1796:Kingdom of SardiniaDuchy of Modena -

1859:Kingdom of Sardinia

1859:Kingdom of Sardinia -

1860:Kingdom of Sardinia

1860:Kingdom of Sardinia

After the annexation of Lombardy, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Emilian Duchies and Pope's Romagna. -

-

maximum expansion of the Kingdom of Sardinia, in 1860

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ↑ The name of the state was originally Latin: Regnum Sardiniae, or Regnum Sardiniae et Corsicae when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is Regno di Sardegna, in Sardinian Rennu de Sardigna and in Piedmontese Regn ëd Sardëgna.

Notes

- ↑ Aldo Sandulli e Giulio Vesperini (2011). "L'organizzazione dello Stato unitario". Rivista trimestrale di diritto pubblico (in Italian): 47–49. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Società Reduci Crimea (1884). Ricordo pittorico militare della spedizione sarda in Oriente 1885-56 (in Italian). p. 11. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ B. MARAGONIS, Annales pisani a.1004–1175, ed. K. PERTZ, in MGH, Scriptores, 19,Hannoverae, 1861/1963, pp. 236–2 and Gli Annales Pisani di Bernardo Maragone, a cura di M. L.GENTILE, in Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, n.e., VI/2, Bologna 1930, pp. 4–7. "1017. Fuit Mugietus reversus in Sardineam, et cepit civitatem edificare ibi atque homines Sardos vivos in cruce murare. Et tunc Pisani et Ianuenses illuc venere, et ille propter pavorem eorum fugit in Africam. Pisani vero et Ianuenses reversi sunt Turrim, in quo insurrexerunt Ianuenses in Pisanos, et Pisani vicerunt illos et eiecerunt eos de Sardinea."

- ↑ C. Zedda-R. Pinna, La nascita dei giudicati, proposta per lo scioglimento di un enigma storiografico, su Archivio Storico Giuridico Sardo di Sassari, vol.n°12, 2007, Dipartimento di Scienze Giuridiche dell'Università di Sassari

- ↑ F. Pinna, Le testimonianze archeologiche relative ai rapporti tra gli Arabi e la Sardegna nel medioevo, in Rivista dell'Istituto di storia dell'Europa mediterranea, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, n°4, 2010

- ↑ Archeological museum of Cagliari, from Santa Sofia church in Villasor

- ↑ "Antiquitas nostra primum Calarense iudicatum, quod tunc erat caput tocius Sardinie, armis subiugavit, et regem Sardinie Musaitum nomine civitati Ianue captum adduxerunt, quem per episcopum qui tunc Ianue erat, aule sacri palatii in Alamanniam mandaverunt, intimantes regnum illius nuper esse additum ditioni Romani imperii." – Oberti Cancellarii, Annales p 71, Georg Heinrich (a cura di) MGH, Scriptores, Hannoverae, 1863, XVIII, pp. 56–96

- ↑ Crónica del califa 'Abd ar-Rahmân III an-Nâsir entre los años 912–942,(al-Muqtabis V), édicion. a cura de P. CHALMETA – F. CORRIENTE, Madrid,1979, p. 365 "Tuesday, August 24th 942 (A.D.), a messenger of the Lord of the island of Sardinia appeared at the gate of al-Nasir ... asking for a treaty of peace and friendship. With him were the merchants, people Malfat, known in al-Andalus as from Amalfi, with the whole range of their precious goods, ingots of pure silver, brocades etc. ... transactions which drew gain and great benefits"

- ↑ Constantini Porphyrogeneti De caerimoniis aulae Byzantinae, in Patrologia cursus completus. Series Graeca CXII, Paris 1857

- ↑ R. CORONEO, Scultura mediobizantina in Sardegna, Nuoro, Poliedro, 2000

- ↑ Roberto Coroneo, Arte in Sardegna dal IV alla metà dell'XI secolo, edizioni AV, Cagliari 2011

- ↑ Barisone Doria: "La senyoria no la tenim ne havem haùda ne del rey ne da regina, e no som tenguts a rey ne a regina axi com eren los dits harons de Sicilia, abans de la dita senyoria e domini obtenim per Madonna Elionor, nostra muller, che és jutgessa d'Arborea e filla e succehidora per son pare per lo jutgat d'Arborea, la qual Casa d'Arborea ha D anys que ha hauda senyioria en la present illa" "We had our lordship not from any king or queen and have not to be loyal to any king or queen as sicilian Barons, because we had our lordship from Madonna Elionor, our wife, who is Judicissa of Arborea, daughter and successor of her father of the judicatus of Arborea, and this House of Arborea has reined for five hundreds years in this island." – Archivo de la Corona d'Aragon. Colleccion de documentos inéditos. XLVIII

- ↑ G. Seche, L'incoronazione di Barisone "Re di Sardegna" in due fonti contemporanee: gli Annales genovesi e gli Annales pisani, in Rivista dell'Istituto di storia dell'Europa mediterranea, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, n°4, 2010

- ↑ Dino Punchu (a cura di), I Libri Iurium della Repubblica de Genova, Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali, Roma, 1996, n°390, pag.334

- ↑ Geronimo Zurita, Los cinco libros postreros de la segunda parte de los Anales de la Corona d'Aragon, Oficino de Domingo de Portonaris y Ursono, Zaragoza, 1629, libro XVII, pag. 75–76

Bibliography

- Murtaugh, Frank M. (1991). Cavour and the Economic Modernization of the Kingdom of Sardinia. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 9780815306719.

- Hearder, Harry (1986). Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento, 1790–1870. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49146-0.

- Martin, George Whitney (1969). The Red Shirt and the Cross of Savoy. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co. ISBN 0-396-05908-2.

- Storrs, Christopher (1999). War, Diplomacy and the Rise of Savoy, 1690–1720. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55146-3.

- AAVV. (a cura di F. Manconi), La società sarda in età spagnola, Cagliari, Consiglio Regionale della Sardegna, 2 voll., 1992-3

- Blasco Ferrer Eduardo, Crestomazia Sarda dei primi secoli, collana Officina Linguistica, Ilisso, Nuoro, 2003, ISBN 9788887825657

- Boscolo Alberto, La Sardegna bizantina e alto giudicale, Edizioni Della TorreCagliari 1978

- Casula francesco Cesare, La storia di Sardegna, Carlo Delfino Editore, Sassari, 1994, ISBN 8871380843

- Coroneo Roberto, Arte in Sardegna dal IV alla metà dell'XI secolo, edizioni AV, Cagliari, 2011

- Coroneo Roberto, Scultura mediobizantina in Sardegna, Nuoro, Poliedro, 2000,

- De Saint-Severin Charles, Souvenirs d'un sejour en Sardaigne pendant les annés 1821 et 1822, Ayné editeur, Lyon, 1827,

- Ferrer i Mallol Maria Teresa, La guerra d'Arborea alla fine del XIV secolo; From Archivo de la Corona d'Aragon. Colleccion de documentos inéditos. XLVIII

- Gallinari Luciano, Il Giudicato di Cagliari tra XI e XIII secolo. Proposte di interpretazioni istituzionali, in Rivista dell'Istituto di Storia dell'Europa Mediterranea, n°5, 2010

- Luttwak Edward, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantin Empire, The Belknap Press, 2009, ISBN 9780674035195

- Manconi Francesco, La Sardegna al tempo degli Asburgo, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2010, ISBN 9788864290102

- Manconi Francesco, Una piccola provincia di un grande impero, CUEC, Cagliari, 2012, ISBN 8884677882

- Mastino Attilio, Storia della Sardegna Antica, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801635

- Meloni Piero, La Sardegna Romana, Chiarella, Sassari, 1980

- Motzo Bachisio Raimondo, Studi sui bizantini in Sardegna e sull'agiografia sarda, Deputazione di Storia Patria della Sardegna, Cagliari, 1987

- Ortu Gian Giacomo, La Sardegna dei Giudici, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801024

- Paulis Giulio, Lingua e cultura nella Sardegna bizantina : testimonianze linguistiche dell'influsso greco, Sassari, L'Asfodelo, 1983

- Spanu Luigi, Cagliari nel seicento, Edizioni Castello, Cagliari, 1999

- Spanu Pier Giorgio, Dalla Sardegna bizantina alla Sardegna Giudicale, in Orientis Radiata Fulgore, la Sardegna nel contesto storico e culturale bizantino, Atti del Convegno di Studi, 30 novembre – 1 dicembre 2007, Nuove Grafiche Puddu Editore, Ortacesus, 2008

- Tola Pasquale, Codex Diplomaticus Sardiniae voll. 1et 2, Historiae Patriae Monumenta, Tipografia Regia, Torino, 1861

- Veyne Paul, L'Empire Greco-Romain, Editeur Seuil, 2005, ISBN 9782020577984

- Zedda Corrado – Pinna Raimondo, La nascita dei Giudicati. Proposta per lo scioglimento di un enigma storiografico, in Archivio Storico Giuridico di Sassari, seconda serie, n° 12, 2007

- Zurita Geronimo, Los cinco libros postreros de la segunda parte de los Anales de la Corona d'Aragon, Oficino de Domingo de Portonaris y Ursono, Zaragoza, 1629

See also

| ||||||||||

| |||||||