Khudabadi script

| Khudabadi | |

|---|---|

The word "Sindhi" written in the Khudabadi script | |

| Type | Abugida |

| Languages | Sindhi language |

| Time period | c. 1500s–1947 (some small scale use still) |

| Parent systems |

Proto-Sinaitic alphabet [a]

|

| Sister systems | Gurmukhī |

|

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

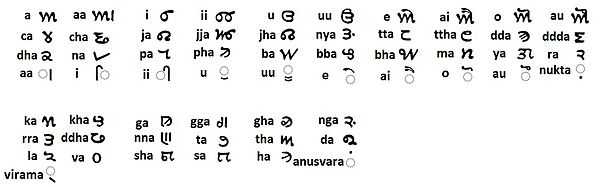

Khudabadi (also known as Vaniki, Hatvaniki or Hatkai) (Sindhi: خدا آبادي، واڻڪي، هٽ واڻڪي، واڻڪي) script is a script used for writing the Sindhi language.[1]

History

The Khudabadi script was invented by the Khudabadi Sindhi Swarankar community. The members of the Swarnakar community, while residing in Khudabad around 1550 CE, felt it necessary to invent a very simple script so that they can send written messages to their relations, who were living far away from them in their own home towns. This necessity mothered the invention of a new script. The new script had forty one consonants but no vowels. And was to be written from left to right, like Sanskrit. It continued to be in use for very long period of time among Khudabadi Sindhi Swarankar. Due to its simplicity, the use of this script spread very quickly and got acceptance in other Sindhi communities, for sending written communications. Because it was originated from Khudabad, it was called Khudabadi script.

The Sindhi traders started maintaining their accounts and other business books in this new script and therefore, later, the Khudabadi script became known as Vaniki, Hatvaniki or Hatkai script. Suddenly, the knowledge of Khudabadi script became an important criterion for employing new persons who intend to go to Sindhwark (overseas), so that their business accounts and books can be kept secret from foreign people and government officials. The Khudabadi script became very popular in Sindh, to the extent that the schools started teaching the Sindhi language in Khudabadi script.

Sindhi language is now generally written in the Arabic script, but it belongs to the Indo-Aryan language family, and over seventy percent of Sindhi words are of Sanskrit origin. Even 300 years after the Muslim conquest, at the time of Mohammed Ghaznavi, the historian Al-Biruni found Sindhi written in three scripts – Ardhanagari, Saindhu and Malwari, all of them variations of Devanagari. When the British arrived they found the Pandits writing Sindhi in Devanagari, Hindu women using Gurmukhi, government servants using some form of Arabic script and traders keeping their business records in an entirely unknown script called Khudabadi.

Under British rule

After Mir Naseer Khan Talpur´s defeat, British rule commenced in Sindh. In the year 1846, Hyderabad saw its own Municipal Corporation. The British Government appointed Mukhi Hiranand as a member of Board of Municipal Corporation. The Collector of Hyderabad used the services of Diwan Bagomal Mukhtiarkar (District Administrator) who knew Arabi Sindhi (written in Arabic script). Mukhi Hiranand knew only Sindhi written in Khudabadi Script. This caused great inconvenience to Collector. Diwan Bagomal, realizing his handicap, learned Sindhi in Khudabadi script from Mukhi Hiranand and obtained a certificate of proficiency from him. This arrangement made office administration work of the Collector easier.[2]

The British scholars found the Sindhi language to be Sanskritic and said that the Devanagari script would be suitable for it, while the government servants, many of whom were Hindus, favoured the Arabic script, since they did not know Devanagari and had to learn it anew. A debate began, with Captain Richard Francis Burton favoring the Arabic script and Captain Stack[3] favouring Devanagari. Sir Bartle Frere, the Commissioner of Sindh, then referred the matter to the Court of Directors of the British East India Company, which directed that:

- The Sindhi Language in Arabic Script for government office use, on the ground that Muslim names could not be written in Devanagari.

- The Education Department should give the instructions to the schools in the script of Sindhi which can meet the circumstance and prejudices of the Mohammadan and Hindu. It is thought necessary to have Arabic Sindhi Schools for Mohammadan where the Arabic Script will be employed for teaching and to have Hindu Sindhi Schools for Hindus where the Khudabadi Script will be employed for teaching.

In the year 1868, the Bombay Presidency assigned Narayan Jagannath Vaidya (Deputy Educational Inspector of Sindh) to replace the Abiad used in Sindhi, with the Khudabadi script. The script was decreed a standard script (modified with ten vowels) by the Bombay Presidency.[4] The Khudabadi script of Sindhi language could not make further progress. But it still remained limited to the traders only. The traders continued to maintain their business records in this script until the independence of Pakistan in 1947.

Competing Sindhi scripts

In July 1853, Sir Richard Francis Burton, an orientalist, with the help of local scholars Munshi Thanwardas and Mirza Sadiq Ali Beg evolved a 52-letter Sindhi alphabet. Since the Arabic script could not express Sindhi sounds, a scheme of dots was worked out for the purpose. As a result, the Sindhi script today, not only has all its own sounds, but, also all the four z's of Arabic. The present script predominantly used in Sindh as well as in many states in India and else, where migrants Hindu Sindhi have settled, is Arabic in Naskh styles having 52 letters. However, in some circles in India, Devanagari is used for writing Sindhi. The Government of India recognizes both scripts.[3]

Unicode

The current proposal to add Khudabadi to the Unicode Standard was written by Anshuman Pandey.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Azimusshan Haider (1974). History of Karachi. Haider. p. 23. OCLC 1604024.

- ↑ Diwan Bherumal Meharchand. "Sindh Je Hindun Jee Tareekh"-1919

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Sindhi Language: Script". Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ "Omniglot: Sindhi alphabets, pronunciation and language". Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ Pandey, Anshuman. 2010. Proposal to Encode the Sindhi Script in ISO/IEC 10646

External links

- Script, SindhiLanguage.com

| |||||||||||