Key (engineering)

In mechanical engineering, a key is a machine element used to connect a rotating machine element to a shaft. The key prevents relative rotation between the two parts and enables torque transmission.A key is used for temporary fastening. For a key to function, the shaft and rotating machine element must have a keyway, also known as a keyseat, which is a slot or pocket the key fits in. The whole system is called a keyed joint.[1][2] A keyed joint still allows relative axial movement between the parts.

Commonly keyed components include gears, pulleys, and couplings.

Types

There are three main types of keys: Sunk, Saddle, and Tangent, Round, and Spline keys.

Sunk key

Types of sunk keys: Rectangular, Square, Parallel sunk, Gib-head, Feather, and Woodruff.

Parallel keys

Parallel keys are the most widely used. They have a square or rectangular cross-section. Square keys are used for smaller shafts and rectangular faced keys are used for shaft diameters over 6.5 in (170 mm) or when the wall thickness of the mating hub is an issue. Set screws often accompany parallel keys to lock the mating parts into place.[3] The keyway is a longitudinal slot in both the shaft and mating part.

-

The keyway in a shaft for a parallel key

-

A sprocket with an internal parallel keyway

-

Cross-section of a parallel keyed joint

Woodruff keys

Woodruff keys are semicircular shaped, such that, when installed, leave a protruding tab. The keyway in the shaft is a semi-circular pocket, the mating part, a longitudinal slot. They are used to improve the concentricity of the shaft and the mating part, which is critical for high speed operation.[3] The main advantage of the Woodruff key is that it eliminates milling a keyway near shaft shoulders, which already have stress concentrations.[4]

Common applications include machine tools, automotive applications, snowblowers and marine propellers.

This type of key was developed by W.N. Woodruff of Connecticut. In 1888, he was awarded the John Scott Medal by the Franklin Institute for his invention.[5]

-

A Woodruff key installed

-

.jpg)

A Woodruff key and keyway

-

Gear G is positively located on shaft S by Woodruff key N

Tapered keys

The tapered key is tapered only on the side that engages the hub. The keyway in the hub has a taper that matches that of the tapered key. Some taper keys have a gib, or tab, for easier removal during disassembly. The purpose of the taper is to secure the key itself, as well as, to firmly engage the shaft to the hub without the need for a set screw. The problem with taper keys is that they can cause the center of the shaft rotation to be slightly off of the mating part.[3] It is different from a tapered shaft lock in that tapered keys have a matching taper on the keyway, while tapered shaft locks do not.

Others

A "Scotch key" or "Dutch key" also provides a keyway not by milling but by drilling axially into the part and the shaft, so that a round key can be used. If the key is tapered, it is referred to as a "Dutch pin" and is driven in, and generally cut off flush with the end of the shaft. A Hirth joint is similar to a Spline joint but with the teeth on the butt of the shaft instead of on the surface.

Spline key

Keyseating

Keyseating is the creation of the slots in the mating items. Keyseating can be done on a variety of different machines including a keyseater, a vertical slotting machine, a broacher, either a vertical or horizontal mill, or with a chisel and file.

-

Keyway cutters

-

Special cutters

-

Slotting tools

-

Different slotting tools

Broaching

Broaching primarily used to cut square cornered internal keyways. The specific broach, bushing and guide are used for each given keyway cross-section, which makes this process more expensive than most of the alternatives. However, it can produce the most accurate keyway out of all the processes. There are three main steps in broaching a keyway: First, the workpiece is set on the arbor press and the bushing is placed in the opening of the workpiece. Next, the broach is inserted and pushed through, cutting the keyway. Finally, shims are placed between the bushing and the broach to achieve the correct depth necessary for the key.[6]

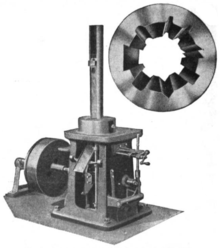

Keyseater

Keyseaters, also known as keyseating machines and keyway cutters, are specialized machines designed to cut keyways. They are very similar to vertical shapers; the difference is that the cutting tool on a keyseater enters the workpiece from the bottom and cuts on the down-stroke, while the tool on a shaper enters the workpiece from the top and cuts downward. Another difference is a keyseater has a guiding system above the workpiece to minimize deflection, which results in a closer tolerance cut. The process starts by clamping the workpiece to the table with a fixture or vise. The workpiece is properly located and then the reciprocating arm is started. Some models have a stationary table so the cutter is fed horizontally into the workpiece, while others have a movable table that feeds the workpiece into a fixed cutter. These machines can cut other straight sided features other than keyways (see the picture). They can also produce blind slots, which are slots that do not extend through the whole workpiece.[7][8]

Milling

Parallel, tapered, and Woodruff keyways can be produced on a milling machine. End mills or slotting cutters are used for parallel and tapered keyways, while a Woodruff cutter is used for Woodruff keyways.[9]

For internal keyways that are not too long, the keyways can be milled if a radius is acceptable.

Chiseling

One of the earliest forms of keyseating was done by chiseling. The keyway is roughed out using a chisel and then filed to size; the key is tried frequently to avoid over filing. This technique is long, tedious, and rarely used anymore.[10]

Keyed joints

Two parallel keys can be used either 90° or 180° apart from each other if the shaft connection needs to be more robust.[3]

Improperly machined keyways that had cutter deflection or drifting occur, may not be strong enough for the required application.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Bhandari, V. B. (2007), Design of machine elements (2nd ed.), Tata McGraw-Hill, p. 340, ISBN 978-0-07-061141-2.

- ↑ Leonard 1908, p. 394.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Keys and Keyways, archived from the original on 2010-03-19, retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ↑ Shigley, Joseph; Charles Mischke (1989), Mechanical Engineering Design (5 ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-331657-1.

- ↑ Garfield, Eugene (2007). "The John Scott Award Recipients from 1826 - present". Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ↑ Krar, S. F. (1983). Machine tool operations. (pp. 84–85). New York: Gregg Division McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Keyseating, retrieved 04-01-2010.

- ↑ Wick, C. H. (1964). Versatility of keyseating. Machinery (NY), 70(8), 138-140.

- ↑ Kibbe, R. R. (1995). Machine tool practices. (5th ed. ed., p. 572). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- ↑ Leonard 1908, p. 40.

- ↑ Romig, J. V. (1926). The Popular Science Monthly. The Popular Science Monthly., 110(5), 72, 124.

Bibliography

- Leonard, W. S. (1908). Machine-shop tools and methods. (7th ed., pp. 39–42). New York: John Wiley & sons, inc.

External links

- Standard Metric Keys & Keyways

- ASME recommended key sizes for inch based units

- What is keyseating?

- Key joint article from the 1979 Great Soviet Encyclopedia.