Kerala

| Kerala കേരളം | |

|---|---|

| State | |

| |

| Nickname(s): God's Own Country | |

| |

| |

| Coordinates (Trivandrum): 8°30′27″N 76°58′19″E / 8.5074°N 76.972°ECoordinates: 8°30′27″N 76°58′19″E / 8.5074°N 76.972°E | |

| Country | India |

| Region | South India |

| Established | 1 November 1956 |

| Capital | Thiruvananthapuram |

| Largest city | Thiruvananthapuram |

| Districts | 14 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Kerala |

| • Governor | Nikhil Kumar[1] |

| • Chief Minister | Oommen Chandy (INC) |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (141* seats) |

| • Parliamentary constituency | 20 |

| • High Court | Kerala High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 38,863 km2 (15,005 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 21st |

| Population (2011)[2] | |

| • Total | 33,387,677 |

| • Rank | 12th |

| • Density | 860/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Keralite, Malayali |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+05:30) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL |

| HDI |

|

| HDI rank | 1st (2011) |

| Literacy | 95.5% |

| Official languages | Malayalam, English |

| Website | kerala.gov.in |

| ^* 140 elected, 1 nominated | |

Kerala /ˈkɛrələ/, regionally referred to as Keralam (കേരളം), is a state in the south-west region of India on the Malabar coast. It was formed on 1 November 1956 as per the States Reorganisation Act by combining various Malayalam-speaking regions. Spread over 38,863 km2 (15,005 sq mi) it is bordered by Karnataka to the north and north east, Tamil Nadu to the east and south, and the Lakshadweep Sea to the west. With 33,387,677 inhabitants as per the 2011 census, Kerala is the twelfth largest state by population and is divided into 14 districts. Malayalam (മലയാളം) is the most widely spoken and official language of the state. The state capital is Thiruvananthapuram, other major cities include Kochi, Kozhikode, Thrissur, and Kollam.

The region was a prominent spice exporter from 3000 BCE to 3rd century. The Chera Dynasty was the first powerful kingdom based in Kerala, though it frequently struggled against attacks from the neighbouring Cholas and Pandyas. During the Chera period Kerala remained an international spice trading center. Later, in the 15th century, the lucrative spice trade attracted Portuguese traders to Kerala, and eventually paved the way for the European colonisation of the whole of India. After independence, Travancore and Cochin joined the Republic of India and Travancore-Cochin was given the status of a state. Later, the state was formed in 1956 by merging the Malabar district, Travancore-Cochin (excluding four southern taluks), and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.

Kerala is the state with the lowest positive population growth rate in India (3.44%) and has a density of 819 people per km2. The state has the highest Human Development Index (HDI) (0.790) in the country according to the Human Development Report 2011.[3] It also has the highest literacy rate 95.5, the highest life expectancy (Almost 77 years) and the highest sex ratio (as defined by number of women per 1000 men: 1,084 women per 1000 men) among all Indian states. Kerala has the lowest homicide rate among Indian states, for 2011 it was 1.1 per 100,000.[4] A survey in 2005 by Transparency International ranked it as the least corrupt state in the country. Kerala has witnessed significant emigration of its people, especially to the Gulf states during the Gulf Boom during the 1970s and early 1980s, and its economy depends significantly on remittances from a large Malayali expatriate community. Hinduism is practised by more than half of the population, followed by Islam and Christianity. The culture of the state traces its roots from 3rd century CE. It is a synthesis of Aryan and Dravidian cultures, developed over centuries under influences from other parts of India and abroad.

Production of pepper and natural rubber contributes to a significant portion of the total national output. In the agricultural sector, coconut, tea, coffee, cashew and spices are important. The state's coastline extends for 590 kilometres (370 mi), and around 1.1 million people of the state are dependent on the fishery industry which contributes 3% of the state's income. The state's 145,704 kilometres (90,536 mi) of roads, constitute 4.2% of all Indian roadways. There are three existing and two proposed international airports. Waterways are also used as a means of transportation. The state has the highest media exposure in India with newspapers publishing in nine different languages; mainly English and Malayalam. Kerala is an important tourist destination, with backwaters, beaches, Ayurvedic tourism, and tropical greenery among its major attractions.

Kerala got selected as state of states in 2013 based on the criteria of GDP Governance, health, education etc. Kerala’s 10% rise in GDP is 3% more than the national GDP. Rise in capital expenditure is 30% against national average of 5%. 35% rise in two-wheelers owners against national average of 15%. Teacher pupil ratio jumped from 2:100 to 4:100.[5]

Etymology

A 3rd-century BCE rock inscription by the Mauryan emperor Asoka the Great refers to the local ruler as Keralaputra (Sanskrit for "son of Kerala"; or "son of Chera[s]", this is contradictory to a popular theory that etymology derives "kerala" from "kera", or coconut tree in Malayalam).[6]

Two thousand years ago, one of three states in the region was called Cheralam in Classical Tamil: Chera and Kera are variants of the same word.[7] The Graeco-Roman trade map Periplus Maris Erythraei refers to this Keralaputra as Celobotra.[8] Ralston Marr derives "Kerala" from the word "Cheral" that refers to the oldest known dynasty of Kerala kings.[9] In turn the word "Cheral" is derived from the proto-Tamil-malayalam word for "lake". Another theory suggests the name is derived from the Arabic "Khair Allah" Arabic: خير الله.[10]

Ancient religious texts

According to Hindu mythology, the land of Kerala was recovered from the sea by Parasurama, an avatar of Vishnu; hence Kerala is also called Parasurama Kshetram ("The Land of Parasurama"). Parasurama was an axe-wielding warrior sage. He threw his axe across the sea, and the water receded as far as it reached. According to legend this new area of land extended from Gokarna to Kanyakumari.[11] Consensus among more scientific geographers agrees that a substantial portion of this area was indeed under the sea in ancient times.[12] The legend later expanded, and found literary expression in the 17th or 18th century with Keralolpathi, which traces the origin of aspects of early Kerala society, such as land tenure and administration, to the story of Parasurama.[13] In medieval times Kuttuvan might have emulated Parasurama tradition of throwing his spear into the sea to symbolize his lordship of the sea.[14] Another much earlier Puranic character associated with Kerala is Mahabali, an Asura and a prototypical king of justice, who ruled the earth from Kerala. He won the war against the Devas, driving them into exile. The Devas pleaded before Lord Vishnu, who took his fifth incarnation as Vamana and pushed Mahabali down to Patala (the netherworld) to placate the Devas. There is a belief that, once a year during the Onam festival, Mahabali returns to Kerala.[15]

The Matsya Purana, which is among the oldest of the 18 Puranas,[16][17] makes the Malaya Mountains of Kerala (and Tamil Nadu) the setting for the story of Lord Matsya, the first incarnation of Lord Vishnu, and King Manu, the first man and the king of the region.[18][19] The earliest Sanskrit text to mention Kerala by name is the Aitareya Aranyaka of the Rigveda.[20] It is also mentioned in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the two great Hindu epics.[21]

History

Pre-history

Prehistorical archaeological findings include dolmens of the Neolithic era in the Marayur area in Idukki district. They are locally known as "muniyara", derived from muni (hermit or sage) and ara (dolmen).[22] Rock engravings in the Edakkal Caves (in Wayanad) are thought to date from the early to late Neolithic eras around 6000 BCE.[23][24] Archaeological studies have identified many Mesolithic, Neolithic and Megalithic sites in Kerala.[25] The studies point to the indigenous development of the ancient Kerala society and its culture beginning from the Paleolithic age, and its continuity through Mesolithic, Neolithic and Megalithic ages.[26] However, foreign cultural contacts have assisted this cultural formation.[27] The studies suggest possible relationship with Indus Valley Civilization during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age.[28]

Ancient period

Kerala was a major spice exporter from as early as 3000 BCE, according to Sumerian records.[29] Its fame as the land of spices attracted ancient Babylonians, Assyrians and Egyptians to the Malabar Coast in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE. Arabs and Phoenicians were also successful in establishing their prominence in the Kerala trade during this early period.[30] The word Kerala is first recorded (as Keralaputra) in a 3rd-century BCE rock inscription (Rock Edict 2) left by the Maurya emperor Asoka (274–237 BCE).[31] The Land of Keralaputra was one of the four independent kingdoms in southern India during Asoka's time, the others being Chola, Pandya, and Satiyaputra.[32] Scholars hold that Keralaputra is an alternate name of the Cheras, the first powerful dynasty based on Kerala.[33][34] These territories once shared a common language and culture, within an area known as Tamiḻakam.[35] While the Cheras ruled the major part of modern Kerala, its southern tip was in the kingdom of Pandyas,[36] which had a trading port sometimes identified in ancient Western sources as Nelcynda (or Neacyndi).[37] At later times the region fell under the control of the Pandyas, Cheras, and Cholas. Ays and Mushikas were two other remarkable dynasties of ancient Kerala, whose kingdoms lay to the south and north of Cheras respectively.[38][39]

In the last centuries BCE the coast became famous among the Greeks and Romans for its spices, especially black pepper. The Cheras had trading links with China, West Asia, Egypt, Greece, and the Roman Empire. In the foreign-trade circles the region was identified by the name Male or Malabar.[40] Muziris, Berkarai, and Nelcynda were among the principal ports at that time.[41] The value of Rome's annual trade with India as a whole was estimated at no less than 50,000,000 sesterces;[42] contemporary Sangam literature describes Roman ships coming to Muziris in Kerala, laden with gold to exchange for pepper. One of the earliest western traders to use the monsoon winds to reach Kerala may have been Eudoxus of Cyzicus, around 118 or 166 BCE, under the patronage of Ptolemy VIII, a king of the Hellenistic Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. Various Roman establishments in the port cities of the region, such as a temple of Augustus and barracks for garrisoned Roman soldiers, are marked in the Tabula Peutingeriana: the only surviving map of the Roman cursus publicus.[43][44]

Merchants from West Asia and Southern Europe established coastal posts and settlements in Kerala.[45] Jewish connection with Kerala started as early as 573 BCE.[46][47] Arabs also had trade links with Kerala, possibly started before the 4th century BCE, as Herodotus (484–413 BCE) noted that goods brought by Arabs from Kerala were sold to the Jews at Eden.[41] They intermarried with local people, and from this mixture the large Muslim Mappila community of Kerala are descended.[48] In the 4th century, some Christians also immigrated from Persia and joined the early Syrian Christian community who trace their origins to the evangelistic activity of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century.[49] Mappila was an honorific title that had been assigned to respected visitors from abroad; and Jewish, Syrian Christian, and Muslim immigration might account for later names of the respective communities: Juda Mappilas, Nasrani Mappilas, and Muslim Mappilas.[50][51] According to the legends of these communities, the earliest Christian churches,[52] mosque,[53] and synagogue (1568 CE)[54] in India were built in Kerala. The combined number of Muslims, Christians, and Jews was relatively small at this early stage. They co-existed harmoniously with each other and with local Hindu society, aided by the commercial benefit from such association.[48]

Early medieval period

Much of history of the region from the 6th to the 8th century is unknown.[31] A Second Chera Kingdom ( c. 800–1102), also known as Kulasekhara dynasty of Mahodayapuram, was established by Kulasekhara Varman, which at its zenith ruled over a territory comprising the whole of modern Kerala and a smaller part of modern Tamil Nadu. During the early part of Kulasekara period, the southern region from Nagerkovil to Thiruvalla was ruled by Ay kings, who lost their power in the 10th century and thus the region became a part of the Kulasekara empire.[55][56] During Kulasekhara rule, Kerala witnessed a flourishing period of art, literature, trade and the Bhakti cult of Hinduism.[57] A Keralite identity, distinct from the Tamils, became linguistically separate during this period.[58] For the local administration, the empire was divided into provinces under the rule of Naduvazhis, with each province comprising a number of Desams under the control of chieftains, called as Desavazhis.[57]

The inhibitions, caused by a series of Chera-Chola wars in the 11th century, resulted in the decline of foreign trade in Kerala ports. Buddhism and Jainism disappeared from the land.[59] The social system became fractured with internal divisions on the lines of caste.[60] Finally, the Kulasekhara dynasty was subjugated in 1102 by the combined attack of Later Pandyas and Later Cholas.[55] However, in the 14th century, Ravi Varma Kulashekhara (1299–1314) of the southern Venad kingdom was able to establish a short-lived supremacy over southern India. After his death, in the absence of a strong central power, the state was fractured into about thirty small warring principalities; most powerful of them were the kingdom of Samuthiri in the north, Venad in the south and Kochi in the middle.[61][62]

Colonial era

The monopoly of maritime spice trade in the Indian Ocean stayed with Arabs during the high and late medieval periods. However, the dominance of Middle East traders got challenged in the European Age of Discovery during which the spice trade, particularly in black pepper, became an influential activity for European traders.[63] Around the 15th century, the Portuguese began to dominate the eastern shipping trade in general, and the spice-trade in particular, culminating in Vasco Da Gama's arrival in Kappad Kozhikode in 1498.[64][65][66] The Zamorin of Calicut permitted the new visitors to trade with his subjects. The Portuguese trade in Calicut prospered with the establishment of a factory and fort in his territory. However, Portuguese attacks on Arab properties in his jurisdiction provoked Zamorin and finally led to conflicts between them. The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between Zamorin and king of Kochi; they allied with Kochi and when Francisco de Almeida was appointed as the Viceroy of Portuguese India in 1505, his headquarters was at Kochi. During his reign, the Portuguese managed to dominate relations with Kochi and established a few fortresses in Malabar coast.[67] Nonetheless, the Portuguese suffered severe setbacks from the attacks of Zamorin forces; especially from naval attacks under the leadership of admirals of Calicut known as Kunjali Marakkars, which compelled them to seek a treaty. In 1571, Portuguese were defeated by the Zamorin forces in the battle at Chaliyam fort.[68]

The weakened Portuguese were ousted by the Dutch East India Company, who took advantage of continuing conflicts between Kozhikode and Kochi to gain control of the trade.[69] The Dutch in turn were weakened by constant battles with Marthanda Varma of the Travancore Royal Family, and were defeated at the Battle of Colachel in 1741.[70] An agreement, known as "Treaty of Mavelikkara", was signed by the Dutch and Travancore in 1753, according to which the Dutch were compelled to detach from all political involvements in the region.[71][72][73] In the meantime, Marthanda Varma annexed many smaller northern kingdoms through military conquests, resulting in the rise of Travancore to a position of preeminence in Kerala.[74]

In 1766, Hyder Ali, the ruler of Mysore invaded northern Kerala.[75] His son and successor, Tipu Sultan, launched campaigns against the expanding British East India Company, resulting in two of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars.[76][77] Tipu ultimately ceded Malabar District and South Kanara to the Company in the 1790s; both were annexed to Madras Presidency of British India in 1792.[78][79][80] The Company forged tributary alliances with Kochi in 1791 and Travancore in 1795.[81] Thus, by the end of 18th century, the whole of Kerala fell under the control of the British, either administered directly or under suzerainty.[82]

There were major revolts in Kerala during its transition to democracy in the 20th century; most notable among them are the 1921 Malabar Rebellion and the 1946 Punnapra-Vayalar uprising in Travancore.[83] In the Malabar Rebellion, Mappila Muslims of Malabar rioted against Hindu zamindars and the British Raj.[84] Some social struggles against caste inequalities also erupted in the early decades of 20th century, leading to the 1936 Temple Entry Proclamation that opened Hindu temples in Travancore to all castes;[85]

Post colonial period

After British India was partitioned in 1947 into India and Pakistan, Travancore and Cochin joined the Union of India and on 1 July 1949 were merged to form Travancore-Cochin.[86] On 1 November 1956, the state of Kerala was formed by the States Reorganisation Act merging the Malabar district, Travancore-Cochin (excluding four southern taluks, which were merged with Tamil Nadu), and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.[87][88] In 1957, elections for the new Kerala Legislative Assembly were held, and a reformist, Communist-led government came to power, under E. M. S. Namboodiripad.[88] It was one of the first Communist government (In 1945, San Marino, a sovereign state in Italy, elected the first[89][90]), which was democratically elected in the world.[91]

Geography

The state is wedged between the Lakshadweep Sea and the Western Ghats. Lying between north latitudes 8°18' and 12°48' and east longitudes 74°52' and 77°22',[92] Kerala experiences the humid equatorial tropic climate. The state has a coast of 590 km (370 mi)[93] and the width of the state varies between 11 and 121 km (22–75 miles).[94] Geographically, Kerala can be divided into three climatically distinct regions: the eastern highlands; rugged and cool mountainous terrain, the central mid-lands; rolling hills, and the western lowlands; coastal plains.[95] The state is located at the extreme southern tip of the Indian subcontinent and lies near the centre of the Indian tectonic plate; hence, it is subject to comparatively low seismic and volcanic activity.[96] Pre-Cambrian and Pleistocene geological formations compose the bulk of Kerala's terrain.[97][98] A catastrophic flood in Kerala in 1341 CE drastically modified its terrain and consequently affected its history; it also created a natural harbor for spice transport.[99]

The eastern region of Kerala consists of high mountains, gorges and deep-cut valleys immediately west of the Western Ghats' rain shadow.[95] Forty-one of Kerala's west-flowing rivers,[100] and three of its east-flowing ones originate in this region.[101][102] The Western Ghats form a wall of mountains interrupted only near Palakkad; hence also known Palghat, where the Palakkad Gap breaks through to provide access to the rest of India.[103] The Western Ghats rise on average to 1,500 m (4920 ft) above sea level,[104] while the highest peaks reach around 2,500 m (8200 ft).[105] Anamudi, the highest peak in south India, is at an elevation of 2,695 metres (8,842 ft).[106] The elevations of the eastern portions of the Nilgiri Hills and Palni Hills range from 250 and 1,000 m (820 and 3300 ft).[107][108]

Kerala's western coastal belt is relatively flat to the eastern region,[109] and is criss-crossed by a network of interconnected brackish canals, lakes, estuaries,[110] and rivers known as the Kerala Backwaters.[111] The state's largest lake Vembanad, dominates the Backwaters; it lies between Alappuzha and Kochi and is more than 200 km2 (77 sq mi) in area.[112] Around 8% of India's waterways are found in Kerala.[113] Kerala's forty-four rivers include the Periyar; 244 km, Bharathapuzha; 209 km, Pamba; 176 km, Chaliyar; 169 km, Kadalundipuzha; 130 km, Chalakudipuzha; 130 km, Valapattanam; 129 km and the Achankovil River; 128 km. The average length of the rivers is 64 km. Many of the rivers are small and entirely fed by monsoon rain.[114] As Kerala's rivers are small and lacking in delta, they are more prone to environmental effects. The rivers face problems such as sand mining and pollution.[115] The state experiences several natural hazards like landslides, floods, lightning and droughts; the state was also affected by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.[116]

Climate

With around 120–140 rainy days per year,[117]:80 Kerala has a wet and maritime tropical climate influenced by the seasonal heavy rains of the southwest summer monsoon and northeast winter monsoon.[118] Around 65% of the rainfall occurs from June to August corresponding to the southwest monsoon, and the rest from September to December corresponding to northeast monsoon.[118] Southwest monsoon; The moisture-laden winds, on reaching the southernmost point of the Indian Peninsula, because of its topography, become divided into two parts: the "Arabian Sea Branch" and the "Bay of Bengal Branch".[119] The "Arabian Sea Branch" of the Southwest Monsoon first hits the Western Ghats in Kerala,[120] thus making the area the first state in India to receive rain from the Southwest Monsoon.[121][122] Northeast monsoon: The distribution of pressure patterns is reversed during this season and the cold winds from North India pick up moisture from the Bay of Bengal and precipitate it in the east coast of peninsular India.[123][124] In Kerala, the influence of the northeast monsoon is seen in southern districts only.[125] Kerala's rainfall averages 3,107 mm (122 in) annually. Some of Kerala's drier lowland regions average only 1,250 mm (49 in); the mountains of eastern Idukki district receive more than 5,000 mm (197 in) of orographic precipitation: the highest in the state. In eastern Kerala, a drier tropical wet and dry climate prevails. During summer, the state is prone to gale force winds, storm surges, cyclone-related torrential downpours, occasional droughts, and rises in sea level.[126]:26, 46, 52 The mean daily temperatures range from 19.8 °C to 36.7 °C.[127] Mean annual temperatures range from 25.0–27.5 °C in the coastal lowlands to 20.0–22.5 °C in the eastern highlands.[126]:65

| Climate data for Kerala | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.4) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

34 (93) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

34 (93) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

| Source: [127] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

| Animal |

|

|---|---|

| Bird |

|

| Flower |

|

| Tree |

|

Most of the biodiversity is concentrated and protected in the Western Ghats. Out of the 4,000 flowering plant species 900 species are medicinal plants; 1,272 of which are endemic to Kerala and 159 threatened.[129]:11 Its 9,400 km2 of forests include tropical wet evergreen and semi-evergreen forests (lower and middle elevations—3,470 km2), tropical moist and dry deciduous forests (mid-elevations—4,100 km2 and 100 km2, respectively), and montane subtropical and temperate (shola) forests (highest elevations—100 km2). Altogether, 24% of Kerala is forested.[129]:12 Two of the world's Ramsar Convention listed wetlands—Lake Sasthamkotta and the Vembanad-Kol wetlands—are in Kerala, as well as 1455.4 km2 of the vast Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Subjected to extensive clearing for cultivation in the 20th century,[130]:6–7 much of the remaining forest cover is now protected from clearfelling.[131] Eastern Kerala's windward mountains shelter tropical moist forests and tropical dry forests, which are common in the Western Ghats.[132][133]

Kerala's fauna are notable for their diversity and high rates of endemism: it includes 102 species of mammals (56 of which are endemic), 476 species of birds, 202 species of freshwater fishes, 169 species of reptiles (139 of them endemic), and 89 species of amphibians (86 endemic).[134] These are threatened by extensive habitat destruction, including soil erosion, landslides, salinisation, and resource extraction. In the forests, sonokeling, Dalbergia latifolia, anjili, mullumurikku, Erythrina, and Cassia number among the more than 1,000 species of trees in Kerala. Other plants include bamboo, wild black pepper, wild cardamom, the calamus rattan palm, and aromatic vetiver grass, Vetiveria zizanioides.[129]:12 Indian Elephant, Bengal Tiger, Indian Leopard, Nilgiri Tahr, Common Palm Civet, and Grizzled Giant Squirrel are also found in the forests.[129]:12, 174–175 Reptiles include the King Cobra, viper, python, and Mugger Crocodile. Kerala's birds include legion—Malabar Trogon, the Great Hornbill, Kerala Laughingthrush, Darter, Southern Hill Myna and several emblematic species. In lakes, wetlands, and waterways, fish such as kadu; stinging catfish and Choottachi; Orange chromide—Etroplus maculatus are found.[129]:163–165

Subdivisions

The state's 14 districts are distributed among Kerala's six regions: North Malabar (far-north Kerala), South Malabar (northern KerTravancore (southern Kerala) and Southern Travancore (far-south Kerala). The districts which serve as the administrative regions for taxation purposes, are further subdivided into 75 taluks; these have fiscal and administrative powers over settlements within their borders, including maintenance of local land records. Taluks of Kerala are further divided into 1453 revenue villages.[135] Consequent to the 73rd and 74th Amendment to the Constitution of India, the Local self-government Institutions are to function as the third tier of Government and it constitutes 14 District Panchayats, 152 Block Panchayats, 978 Grama Panchayats, 60 Municipalities, 5 Corporations and 1 Township.[136] Mahé, a part of the Indian union territory of Puducherry,[137] though 647 km away from it,[138] is a coastal exclave surrounded by Kerala on all of its landward approaches.[139]

In India, self-governance of the major cities rests with Municipal corporations; there are five such bodies governing Thiruvananthapuram, Kochi, Kozhikode, Kollam and Thrissur.[140] Kochi metropolitan area is the largest urban agglomeration in Kerala.[141] According to a survey by economics research firm, Indicus Analytics, Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode, Kochi, Thrissur and Kannur found place in the 10 best cities in India to spend life; the survey used parameters such as health, education, environment, safety, public facilities and entertainment to rank the cities.[142]

Government and administration

Kerala hosts two major political alliances: the United Democratic Front (India) (UDF); led by the Indian National Congress and the Left Democratic Front (Kerala) (LDF); led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)). At present, the UDF is the ruling coalition in government; Oommen Chandy of the Indian National Congress is the Chief Minister while V.S. Achuthanandan of the LDF is the Leader of Opposition. Strikes, protests and marches are ubiquitous in Kerala because of the comparatively strong presence of labour unions.[143][144] According to the Constitution of India, Kerala has a parliamentary system of representative democracy for its governance; universal suffrage is granted to state residents.[145] The government structure is organised into the three branches:

- Legislature: The unicameral legislature, the Kerala Legislative Assembly, comprises elected members and special office bearers; the Speaker and Deputy Speaker elected by the members from among themselves. Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker and in the Speaker's absence, by the Deputy Speaker. The state has 140 assembly constituencies.[146] The state elects 20 and nine members for representation in the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha respectively.[147]

- Executive: The Governor of Kerala is the constitutional head of state, and is appointed by the President of India.[148] Shri Nikhil Kumar is the Governor of Kerala.[149] The executive authority is headed by the Chief Minister of Kerala, who is the de facto head of state and is vested with extensive executive powers; the head of the party attaining majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed to the post by the Governor.[148] The Council of Ministers, has its members appointed by the Governor, taking the advice of the Chief Minister.[148] Auxiliary authorities known as panchayats, for which local body elections are regularly held, govern local affairs.[150]

- Judiciary: The judiciary consists of the Kerala High Court and a system of lower courts.[151] The High Court, located at Kochi,[152] has a Chief Justice along with 23 permanent and seven additional pro tempore justices as of 2012.[153] The high court also hears cases from the Union Territory of Lakshadweep.[154][155]

The local self-government bodies; Panchayat, Municipalities and Corporations existed in Kerala since 1959, however, the major initiative to decentralise the governance was started in 1993, conforming to the constitutional amendments of central government in this direction.[156] With the enactment of Kerala Panchayati Raj Act and Kerala Municipality Act in the year 1994, the state implemented various reforms in the local self-governance.[157] Kerala Panchayati Raj Act envisages a 3-tier system of local-government with Gram panchayat, Block panchayat and District Panchayat forming a hierarchy.[158] The acts ensure clear demarcation of power among these institutions.[156] However, Kerala Municipality Act envisages a single-tier system for urban areas, with the institution of municipality designed at par with Gram panchayat of the former system. Substantial administrative, legal and financial powers are delegated to these bodies to ensure efficient decentralisation.[159] As per the present norms, the state government devolves about 40 per cent of the state plan outlay to the local government.[160]

Economy

After independence, the state was managed as a democratic socialist welfare economy. From the 90s, liberalisation of the mixed economy allowed onerous Licence Raj restrictions against capitalism and foreign direct investment to be lightened, leading to economic expansion and increase in employment. In the fiscal years 2007–2008, the nominal gross state domestic product (GSDP) was ![]() 162414.79 crore (US$26 billion). GSDP growth; 9.2% in 2004–2005 and 7.4% in 2003–2004 had been high compared to average of 2.3% annually in the 80s and between 5.1%[161]:8 and 5.99%[162] in the 90s.[161]:8 The state recorded 8.93% growth in enterprises from 1998 to 2005, higher than the nation's rate of 4.80%.[163] Human Development Index rating is the highest in India; 0.790.[164] This apparently paradoxical "Kerala phenomenon" or "Kerala model of development" of very high human development and not much high economic development resulted due to a stronger service sector.[126]:48[165]:1

162414.79 crore (US$26 billion). GSDP growth; 9.2% in 2004–2005 and 7.4% in 2003–2004 had been high compared to average of 2.3% annually in the 80s and between 5.1%[161]:8 and 5.99%[162] in the 90s.[161]:8 The state recorded 8.93% growth in enterprises from 1998 to 2005, higher than the nation's rate of 4.80%.[163] Human Development Index rating is the highest in India; 0.790.[164] This apparently paradoxical "Kerala phenomenon" or "Kerala model of development" of very high human development and not much high economic development resulted due to a stronger service sector.[126]:48[165]:1

Kerala's economy depends on emigrants working in foreign countries, mainly in the Gulf states countries such as United Arab Emirates or Saudi Arabia), and remittances annually contribute more than a fifth of GSDP.[166] As of 2008, the Gulf countries altogether had a Keralite population of more than 2.5 million, who send home annually a sum of US$6.81 billion, which is more than 15.13% of remittance to India in 2008; the highest among Indian states.[167] Of the $71 billion in remittances sent to India in 2012, Kerala still received the highest among the states: $11.3 billion, which is nearly 16%.[168]

According to a study commissioned by the Kerala State Planning Board, the state should look for other reliable sources instead of relying on remittances to finance its expenditure.[169]

Tertiary sector, comprising transport, storage, communications, tourism, banking and insurance, real estate and other services, contributed 63.22% of the state GDP in 2011-2012. Agriculture and allied sectors contributed 15.73% while manufacturing, construction and utilities contributed only 21.05% of the GDP.[170][171] Nearly half of Kerala's people are dependent on agriculture alone for income.[172] Around 600 varieties[129]:5 of rice which are Kerala's most important staple food and cereal crop[173]:5 are harvested from 3105.21 km2; a decline from 5883.4 km2 in 1990[173]:5. While, 688,859 tonne paddy are produced per annum.[174] Other key crops include coconut; 899,198 ha, tea, coffee; 23% of Indian production,[175]:13 or 57,000 tonnes[175]:6–7), rubber, cashews, and spices—including pepper, cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Around 1.050 million fishermen haul an annual catch of 668,000 tonnes as of 1999–2000 estimate; 222 fishing villages are strung along the 590 km coast. Another 113 fishing villages dot the hinterland. Kerala's coastal belt of Karunagappally is known for high background radiation from thorium-containing monazite sand. In some coastal panchayats, median outdoor radiation levels are more than 4 mGy/yr and, in certain locations on the coast, it is as high as 70 mGy/yr.[176]

Traditional industries manufacturing items; coir, handlooms, and handicrafts employ around one million people.[177] As per the 2006-07 census by SIDBI there are 1,468,104 Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Kerala employing 3,031,272 people.[178][179] The KSIDC has promoted more than 650 medium and large manufacturing firms in Kerala generating employment for 72,500 people.[180] A small mining sector of 0.3% of GSDP involves extraction of ilmenite, kaolin, bauxite, silica, quartz, rutile, zircon, and sillimanite.[174] Home gardens and animal husbandry also provide work for many people. Other major sectors are tourism, manufacturing, and business process outsourcing. As of March 2002, Kerala's banking sector comprised 3341 local branches; each branch served 10,000 persons, lower than the national average of 16,000; the state has the third-highest bank penetration among Indian states.[181] On 1 October 2011, Kerala became the first state in the country to have at least one banking facility in every village.[182] Unemployment in 2007 was estimated at 9.4%;[183] underemployment, low employability of youths, and a 13.5% female participation rate are chronic issues,[184]:5, 13 as is the practice of Nokku kooli, 'wages for looking on'.[185] By 1999–2000, the rural and urban poverty rates dropped to 10.0% and 9.6% respectively.[186]

Technopark, Trivandrum is the largest IT employer in Kerala and employs 35,000 people. It was the first technology park in India[187][188] and with the inauguration of the Thejaswini complex on 22 February 2007, Technopark became the largest IT Park in India.[189] Software giants like Infosys, Oracle, TCS, Capgemini, HCL, USTGlobal, Nest, Suntec, IBS etc. have offices here.[190] Trivandrum is also the IT Hub of Kerala and hold around 80% of the software exports.[191] Another IT Park, Technocity is also in the making . The Grand Kerala Shopping Festival (GKSF) claimed to be Asia's largest shopping festival was started in the year 2007.[192] Since then it has become an annual shopping event being conducted in the December–January period.

The state's budget of 2012–2013 is ![]() 481.42 billion.[193] The state government's tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) amounted to

481.42 billion.[193] The state government's tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) amounted to ![]() 217.22 billion in 2010–2011; up from

217.22 billion in 2010–2011; up from ![]() 176.25 billion in 2009–2010. Its non-tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) of the Government of Kerala reached

176.25 billion in 2009–2010. Its non-tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) of the Government of Kerala reached ![]() 19,308 million in 2010–2011.[193] However, Kerala's high ratio of taxation to GSDP has not alleviated chronic budget deficits and unsustainable levels of government debt, which have impacted social services.[194] A record total of 223 hartals were observed in 2006, resulting in a revenue loss of over

19,308 million in 2010–2011.[193] However, Kerala's high ratio of taxation to GSDP has not alleviated chronic budget deficits and unsustainable levels of government debt, which have impacted social services.[194] A record total of 223 hartals were observed in 2006, resulting in a revenue loss of over ![]() 2000 crore (

2000 crore (![]() 20 billion).[195]

20 billion).[195]

Agriculture

Agriculture in Kerala has passed through many phases. The major change occurred in the 1970s, when production of rice reduced due to increased availability of rice supply all over India and decreased availability of labour supply.[196] Consequently, investment in rice production decreased and a major portion of the land shifted to the cultivation of perennial tree crops and seasonal crops.[197][198] Profitability of crops is reducing due to shortage of farm labour, the high price of land and the uneconomic size of operational holdings.[199]

Kerala produces 97% of the national output of black pepper[200] and accounts for 85% of the area under natural rubber in the country.[201][202] Coconut, tea, coffee, cashew, and spices—including cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg—comprise a critical agricultural sector.[203][204][205][206][207][208] The key agricultural staple is rice, with varieties grown in extensive paddy fields.[209] Home gardens comprise a significant portion of the agricultural sector.[210] Related animal husbandry is also important, and is touted by proponents as a means of alleviating rural poverty and unemployment among women, the marginalised, and the landless.[211][212] The state government promotes these activity via educational campaigns and the development of new cattle breeds such as the Sunandini.[213][214][215]

Though the contribution of agricultural sector to the state economy was on the decline in 2012-13, under the strength of the allied livestock sector, it has picked up from 7.03% (2011–12) to 7.2%. In the current fiscal(2013–14), the contribution has been estimated at a high of 7.75%. The total growth of farm sector has recorded a 4.39% increase in 2012-13, over a paltry 1.3% growth in the previous fiscal.The primary sector comprising agriculture has only a share of 9.34% in the sectoral distribution of Gross State Domestic Product at Constant Price, whereas the secondary and tertiary sectors has contributed 23.94% and 66.72% respectively.

Fisheries

With 590 km of coastal belt,[216] 400,000 hectares of inland water resources[217] and about 220,000 active fishermen,[218] Kerala is one of the leading producers of fish in India.[219] According to 2003–04 reports, about 1.1 million people earn their livelihood from fishing and allied activities such as drying, processing, packaging, exporting and transporting fisheries. The annual yield of the sector was estimated as 608,000 tons in 2003–04.[220] This contributes to about 3% of the total economy of the state. In 2006, about 22% of the total Indian marine fishery yield was from the state.[221] During the southwest monsoon, a suspended mud bank would be developed along the shore, which in turn leads to calm ocean water and hence peak output from the fishery industry. This phenomenon is locally called chakara.[222][223] The fish landings consist of a large variety: pelagic species; 59%, demersal species; 23%, crustaceans and molluscs.[221]

Transport

Roads

Kerala has 145,704 kilometres (90,536 mi) of roads; it accounts for 4.2% of India's total. This translates to about 4.62 kilometres (2.87 mi) of road per thousand population, compared to an average of 2.59 kilometres (1.61 mi) in the country. Roads in Kerala include 1,524 km of national highway; it is 2.6% of the nation's total, 4341.6 km of state highway and 18900 km of district roads.[224] Most of Kerala's west coast is accessible through two national highways: NH 47 and NH 17, and the eastern side is accessible through various state highways.[225] There is also a hill highway proposed, to make easy access to eastern hills.[226] National Highway 17 with the longest stretch of 421 km connects Edapally to Panvel; it starts from Kochi and passes through Kozhikode, Kannur and Kasaragod before entering Karnataka.[225]

The Department of Public Works is responsible for maintaining and expanding the state highways system and major district roads.[227] The Kerala State Transport Project (KSTP), which includes the GIS-based Road Information and Management Project (RIMS), is responsible for maintaining and expanding the state highways in Kerala; it also oversees a few major district roads.[228][229] Traffic in Kerala has been growing at a rate of 10–11% every year, resulting in high traffic and pressure on the roads. Road density is nearly four times the national average, reflecting the state's high population density. Kerala's annual total of road accidents is among the nation's highest. The accidents are mainly the result of the narrow roads and irresponsible driving.[230] National Highways in Kerala are the narrowest compared to other parts of the country and will remain so for unforeseeable future, as Kerala state government has requested and got special approval(exemption) for narrow national highways in the state compared to other parts of the country. In Kerala, highways will be 45-meters wide, where as in other states National Highways are minimum 4 lane, 60-meters wide, grade separated highways as well as 6/8 lane access-controlled expressways.[231][232] NHAI has threatened the kerala state government that it will give high priority to other states in highway development as political commitment to the better highways has been lacking from the government,[233] although State had the highest road accident rate in the country, with most fatal accidents taking place along the State’s NHs.[234]

Railways

The Indian Railways' Southern Railway line runs through the state connecting most of the major towns and cities except those in the highland districts of Idukki and Wayanad.[235] The railway network in the state is controlled by two out of six divisions of Southern Railway; Thiruvananthapuram Railway division and Palakkad Railway Division.[236] Thiruvananthapuram Central (TVC) is the busiest railway station in the state. Kerala's major railway stations are Kannur (CAN), Kozhikode (CLT), Tirur (TIR), Shornur Junction (SRR), Palakkad Junction (PGT), Thrissur Railway Station (TCR),Angamaly (AFK), Aluva (AWY), Ernakulam Town (North) (ERN), Ernakulam Junction (South) (ERS), Alappuzha (ALLP), Kottayam (KTYM), Tiruvalla (TRVL), Chengannur (CNGR), Kayamkulam Junction (KYJ), Kollam Junction (QLN) and Thiruvananthapuram Central (TVC).

Major railway transport between Beypore–Tirur began on 12 March 1861, from Shoranur–Cochin Harbour section in 1902, from Shenkottai–Punalur on 26 November 1904, from Nilambur-Shoranur in 1927, from Punalur–Thiruvananthapuramon 4 November 1931, from Ernakulam–Kottayam in 1956, from Kottayam–Kollam in 1958, from Thiruvananthapuram–Kanyakumari in 1979 and from Thrissur-Guruvayur Section in 1994.[237]

Airports

Kerala has three international airports; Trivandrum International Airport, Cochin International Airport and Calicut International Airport. Two international airports were proposed, at Kannur and Pathanamthitta as of 2008.[238] Officials say that the Kannur International Airport will be completed in December 2015 and will make Kerala the only state in the country to have four international airports.[239][240] The Cochin International Airport is the largest and busiest in the state, and was the first Indian airport to be incorporated as a public limited company; it was funded by nearly 10,000 non-resident Indians from 30 countries.[241]

Inland water transport

As Kerala has numerous backwaters, waterways are used for commercial inland navigation. The transportation is mainly done with country craft and passenger vessels.[198] There are 67 navigable rivers in the state. The total length of the inland waterways in the state is 1687 km.[242] The main constraints to the expansion of inland navigation are lack of depth in the waterway caused by silting, lack of maintenance of navigation system and bank protection, accelerated growth of the water hyacinth, lack of modern inland craft terminals, and lack of a cargo handling system.[198] A 205 km canal, National Waterway 3, runs between Kottapuram and Kollam.[243]

Demographics

| Population trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1951 | 13,549,000 | ||

| 1961 | 16,904,000 | 24.8% | |

| 1971 | 21,347,000 | 26.3% | |

| 1981 | 25,454,000 | 19.2% | |

| 1991 | 29,099,000 | 14.3% | |

| 2001 | 31,841,000 | 9.4% | |

| 2011 | 33,388,000 | 4.9% | |

| Source: 2001 & 2011 Censuses of India[244][245][246] | |||

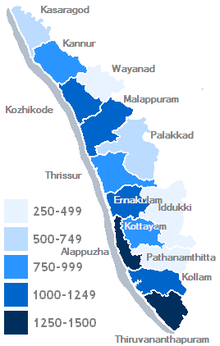

Kerala is home to 2.76% of India's population; at 859 persons per km2, its land is nearly three times as densely settled as the rest of India, which is at a population density of 370 persons per km2.[247] Trivandrum is the largest and most populous city in Kerala. In the state, the rate of population growth is India's lowest, and the decadal growth of 4.9% in 2011 is less than one third of the all-India average of 17.64%.[247] Kerala's population more than doubled between 1951 and 1991 by adding 15.6 million people to reach 29.1 million residents in 1991; the population stood at 33.3 million by 2011.[247] Kerala's coastal regions are the most densely settled, leaving the eastern hills and mountains comparatively sparsely populated.[citation needed] Around 31.8 million Keralites are predominantly of Malayali descent.[citation needed] State's 321,000 indigenous tribal Adivasis, 1.10% of the population, are concentrated in the east.[248]:10–12 Malayalam, one of the classical languages in India, is Kerala's official language,[249] however Tamil is also widely understood.[250][251][252] Kannada, Tulu, Hindi, Bengali, Mahl and various Adivasi (tribal) languages are also spoken.[251][253][254][255] As of early 2013, there are close to 2.5 million (7.5% of state population) migrant workers from other states of India in Kerala.[256]

Religion

In comparison with the rest of India, Kerala experiences relatively little sectarianism.[258] According to 2001 Census of India figures, 56.2% of Kerala's residents are Hindus, 24.7% are Muslims, 19% are Christians, and the remaining 0.1% follows other religions.[259] The major Hindu castes are Dalit, Ezhava,Thiyya, Nadars, Nair and Nambudiri. The rest of the Hindu castes, including those in the list of Other Backward Class (OBC), are minority communities. Islam and Judaism arrived in Kerala through Arab traders.[260] Muslims of Kerala, generally referred to as Moplahs, mostly follow the Shafi'i Madh'hab under Sunni Islam.[261] The major Muslim organisations are Sunni, Mujahid and Jama'at-e-Islami.[262] Christianity is believed to have reached the shores of Kerala in 52 AD with the arrival of St Thomas, one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ.[263][264] Saint Thomas Christians include Syro-Malabar Catholic,[265] Syro-Malankara Catholic,[266] Malankara Orthodox,[267] Jacobite[268] and Marthoma.[269] Latin Rite Christians were converted by the Portuguese in the 16th and 19th centuries,[127][270] mainly from communities where fishing was the traditional occupation.[271] A significant Jewish community existed in Kerala until the 20th century, when most of them migrated to Israel.[272] Jainism has a considerable following in the Wayanad district.[273][274] Buddhism was dominant at the time of Ashoka the Great but vanished by the 8th century CE.[275]

The Paradesi Synagogue at Kochi is the oldest synagogue in the Commonwealth.[276] Certain Hindu communities such as the Kshatriyas, Nairs, Tiyyas and the Muslims around North Malabar used to follow a traditional matrilineal system known as marumakkathayam,[277][278] although this practice ended in the years after Indian independence.[279] Other Muslims, Christians, and some Hindu castes such as the Namboothiris and the Ezhavas followed makkathayam, a patrilineal system.[280][281][282] Owing to the former matrilineal system, women in Kerala enjoy a high social status.[283] However, gender inequality among low caste men and women is reportedly higher compared to that in other castes.[284] :1

Gender

There are a number of possible explanations for the position of women in Kerala. One is the rise of communist governing bodies in Kerala. These governments helped to distribute land and implement education reforms. Another explanation is a tradition of matrilineal inheritance in Kerala.[283] This was common among certain influential castes and is a factor in the value placed on daughters. Christian missionaries also influenced Malayali women in that they started schools for girls from poor families. Opportunities for women like education and gainful employment often translate into a lower birth rate, which in turn, makes education and employment more likely to be accessible and more beneficial for women. This creates an upward spiral for both the women and children of the community that is passed on to future generations of both boys and girls. Low birth rate and high literacy rate are often the twin hallmarks of the healthy advancement of a society.

While having the opportunities that education affords them such as participating in politics, keeping up to date on news, reading religious texts, etc., these tools have not translated into full, equal rights for the women of Kerala. At Cochin University women must be in their hostels by dark, while men are free to roam at any hour. There is a general attitude that women must be restricted for their own benefit. Women who break the rules are often looked down on. Kerala is a state in flux where, despite the social progress made so far, gender still influences social mobility.[285][286][287]

Human Development Index

As of 2011 Kerala has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.790 which comes under the "very high" category and it is the highest in the country.[3] Comparatively higher spending of the government in primary level education, health care and elimination of poverty from the 19th century onward had helped the state to keep a very high HDI;[288][289] report was prepared by the central government's Institute of Applied Manpower Research.[290][291] However, the Human Development Report, 2005 prepared by Centre for Development Studies envisages a virtuous phase of inclusive development for the state since the advancement in human development had already started aiding the economic development of the state.[288]

According to a 2005–2006 national survey, Kerala has the highest literacy rate among Indian states; 93.91%.[292] Life expectancy of 74 years was among the highest in India as of 2011.[293] Kerala's rural poverty rate fell from 69% (1970–1971) to 12% (2010); the overall (urban and rural) rate fell 47% between the 1970s and 2000s.[citation needed] By 1999–2000, the rural and urban poverty rates dropped to 10.0% and 9.6% respectively.[186] These changes stem largely from efforts begun in the late 19th century by the kingdoms of Cochin and Travancore to boost social welfare.[294][295] This focus was maintained by Kerala's post-independence government.[126][164]:48 The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organisation designated Kerala the world's first "baby-friendly state" because of its effective promotion of breast-feeding over formulas.[296] As of 2004, more than 95% of births were hospital-delivered.[297]:6 Ayurveda (both elite and popular forms),[298]:13 siddha, and many endangered and endemic modes of traditional medicine, including kalari, marmachikitsa and vishavaidyam, are practised. Some occupational communities such as Kaniyar were known as native medicine men in relation with practice of such streams of medical systems, apart from their traditional vocation.[299] These propagate via gurukula discipleship,[298]:5–6 and comprise a fusion of both medicinal and supernatural treatments.[298]:15

Kerala has undergone the "demographic transition" characteristic of such developed nations as Canada, Japan, and Norway.[165]:1 as 11.2% of people are over the age of 60,[164] and due to the low birthrate of 18 per 1,000.[300] In 1991, Kerala's total fertility rate (TFR) was the lowest in India. Hindus had a TFR of 1.66, Christians; 1.78, and Muslims; 2.97.[301] The sub-replacement fertility level and infant mortality rate are lower compared to those of other states; estimated from 12[126][300]:49 to 14[302]:5 deaths per 1,000 live births. According to Human Development Report 1996, Kerala's Gender Development Index was reported to be 597; higher than any other state of India. Many factors, such as high rates of female literacy, education, work participation and life expectancy, along with favourable female-to-male ratio, had contributed to it.[303] Kerala's female-to-male ratio of 1.058 is higher than that of the rest of India.[165]:2. The state also is regarded as the "least corrupt Indian state" according to the surveys conducted by Transparency International (2005)[304] and India Today (1997)[305]

Kerala is the cleanest and healthiest state in India.[306] However, Kerala's morbidity rate is higher than that of any other Indian state—118 (rural) and 88 (urban) per 1,000 people. The corresponding figures for all India were 55 and 54 per 1,000 respectively as of 2004.[302]:5 Kerala's 13.3% prevalence of low birth weight is higher than that of First World nations.[300] Outbreaks of water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis, and typhoid among the more than 50% of people who rely on 3 million water wells is an issue worsened by the lack of sewers.[307]:5–7 In respect of women empowerment, some negative factors such as higher suicide rate, lower share of earned income, complaints of sexual harassment and limited freedom are reported.[303]

Education

The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries. In attempting to solve astronomical problems, the Kerala school independently created a number of important mathematics concepts including results—series expansion for trigonometric functions.[308][309] Following the instructions of the Wood's despatch of 1854, both the princely states, Travancore and Cochin, launched mass education drives with the support from different agencies mainly based on castes and communities and introduced a system of grant-in-aid to attract more private initiatives.[310] The efforts by leaders, Vaikunda Swami, Narayana Guru and Ayyankali, towards the socially discriminated castes in the state, with the help of community-based organisations like Nair Service Society, SNDP, Muslim Mahajana Sabha, Yoga Kshema Sabha (of Nambudiris) and different congregations of Christian churches, led to developement in the mass education of Kerala.[310]

In 1991, Kerala became the first state in India to be recognised as a completely literate state, though the effective literacy rate at that time was only 90%. As of 2007, the net enrollment in elementary education was almost 100 per cent and was almost balanced among different sexes, social groups and regions, unlike other states of India.[311] The state topped the Education Development Index (EDI) among 21 major states in India in the year 2006–2007.[312] According to the first Economic Census, conducted in 1977, 99.7% of the villages in Kerala had a primary school within 2 km, 98.6% had a middle school within 2 km and 96.7% had a high school or higher secondary school within 5 km.[313]

The educational system prevailing in the state schooling is for 10 years, which are streamlined into lower primary, upper primary and secondary school stages with a 4+3+3 pattern.[311] After 10 years of secondary schooling, students typically enroll in Higher Secondary Schooling in one of the three major streams—liberal arts, commerce or science.[314] Upon completing the required coursework, students can enroll in general or professional under-graduate (UG) programmes. The majority of the public schools are affiliated with the Kerala State Education Board. Other familiar educational boards are the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), and the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS). English is the language of instruction in most self-financing schools, while government and government-aided schools offer English or Malayalam.[314] Though the education cost is generally considered low in Kerala,[315] according to the 61st round of the National Sample Survey (2004–2005), per capita spending on education by the rural households in Kerala was reported to be ![]() 41 for Kerala, more than twice the national average. The survey also revealed that the rural-urban difference in the household expenditure on education was much less in Kerala than in the rest of India.[316]

41 for Kerala, more than twice the national average. The survey also revealed that the rural-urban difference in the household expenditure on education was much less in Kerala than in the rest of India.[316]

Universities in Kerala are Central University of Kerala, Kannur University, Mahatma Gandhi University, University of Calicut, National University of Advanced Legal Studies, University of Kerala, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kerala Agricultural University, Aligarh Muslim University Malappuram, Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, EFLU Malappuram Campus, and an islamic university (Darul Huda Islamic university). Premier educational institutions in Kerala are the Indian Institute of Management, Kozhikode, National Institute of Technology Calicut (NITC) and the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology, Trivandrum (IIST). The Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Thiruvananthapuram (IISER-TVM) College of Engineering Trivandrum (Trivandrum)

Culture

The culture of Kerala is composite and cosmopolitan in nature and it's an integral part of Indian culture.[21] It has been elaborated through centuries of contact with neighboring and overseas cultures.[317] However, the geographical insularity of Kerala from the rest of the country has resulted in development of a distinctive lifestyle, art, architecture, language, literature and social institutions.[21] There are around 10,000 festivals celebrated in the state.[318] The Malayalam calendar, a solar calendar started from 825 CE in Kerala,[319] finds common usage in planning agricultural and religious activities.[320]

Dance

Kerala is home to a number of performance arts. These include five classical dance forms: Kathakali, Mohiniyattam, Koodiyattom, Thullal and Krishnanattam, originated and developed in the temple theatres during the classical period under the patronage of royal houses.[321] Kerala natanam, Kaliyattam, Theyyam, Koothu and Padayani are other dance forms associated with the temple culture of the region.[322] Some traditional dance forms such as Margamkali, Parichamuttu and Chavittu nadakom are popular among the Christians,[323][324][325] while Oppana and Duffmuttu are popular among the Muslims of the state.[323][326]

Music

Development of classical music in Kerala is attributed to the contributions it received from the traditional performance arts associated with the temple culture of Kerala.[327] Development of the indigenous classical music form, Sopana Sangeetham, illustrates the rich contribution that temple culture has made to the arts of Kerala.[327] Carnatic music dominates Keralite traditional music. This was the result of Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma's popularisation of the genre in the 19th century.[317] Raga-based renditions known as sopanam accompany kathakali performances.[328] Melam; including the paandi and panchari variants, is a more percussive style of music:[329] it is performed at Kshetram-centered festivals using the chenda.[330] Panchavadyam is a different form of percussion ensemble, in which artists use five types of percussion instrument.[331] Kerala's visual arts range from traditional murals to the works of Raja Ravi Varma, the state's most renowned painter.[327] Most of the castes and communities in Kerala have rich collections of folk songs and ballads associated with a variety of themes; Vadakkan Pattukal (Northern Ballads), Thekkan pattukal (Southern Ballads), Vanchi pattukal (Boat Songs), Mappila Pattukal (Muslim songs) and Pallipattukal (Church songs) are a few of them.[332]

Cinema

Malayalam films carved a niche for themselves in the Indian film industry with the presentation of social themes.[333][334] Directors from Kerala, like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, John Abraham, Kamal and G. Aravindan, have made a considerable contribution to the Indian parallel cinema. Kerala has also given birth to numerous actors, such as Satyan, Bharath Gopi, Prem Nazir,Jayan Mohanlal, Mamooty, Suresh Gopi, Dileep, Murali, Oduvil Unnikrishnan, Cochin Haneefa, Thilakan and Nedumudi Venu. Late Malayalam actor Prem Nazir holds the world record for having acted as the protagonist of over 720 movies.[335] Since the 1980s, actors Mammootty and Mohanlal have dominated the movie industry; Mammootty has won three National Awards for best actor while Mohanlal has two to his credit.[336]

Literature

Malayalam literature starts from the late medieval period and includes such notable writers as the 14th-century Niranam poets (Madhava Panikkar, Sankara Panikkar and Rama Panikkar),[337][338] and the 17th-century poet Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan, whose works mark the dawn of both modern Malayalam language and poetry.[339][340] Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar and Kerala Varma Valiakoi Thampuran are noted for their contribution to Malayalam prose.[341][342][343] The "triumvirate of poets" (Kavithrayam): Kumaran Asan, Vallathol Narayana Menon, and Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer, are recognised for moving Keralite poetry away from archaic sophistry and metaphysics, and towards a more lyrical mode.[344][345][346]

In the second half of the 20th century, Jnanpith winning poets and writers like G. Sankara Kurup, S. K. Pottekkatt, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, M. T. Vasudevan Nair and O. N. V. Kurup had made valuable contributions to the modern Malayalam literature.[347][348][349][350][351] Later, writers like O. V. Vijayan, Kamaladas, M. Mukundan, Arundhati Roy, had gained international recognition.[352][353][354][355]

Cuisine

Kerala cuisine has a multitude of both vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes prepared using fish, poultry and meat. Culinary spices have been cultivated in Kerala for millennia and they are characteristic of its cuisine.[356] Rice is a dominant staple that is eaten at all times of day.[357] Breakfast dishes are frequently based on the rice preparations idli, puttu, Idiyappam, or pulse-based vada or tapioca.[358] These may be accompanied by chutney, kadala, payasam, payar pappadam, Appam, chicken curry, beef fry, egg masala and fish curry.[204] Lunch dishes include rice and curry along with rasam, pulisherry and sambar.[359] Sadhya is a vegetarian meal, often served on a banana leaf and followed with a cup of payasam.[360] Popular snacks include banana chips, yam crisps, tapioca chips, unniyappam and kuzhalappam.[361][362][363] Sea food specialities include karimeen, prawn, shrimp and other crustacean dishes.[364] Kerala is one of the only places in India where there is no communal distinction between the different food types. People of all religions share the same vegetarian and non vegetarian dishes.

Elephants

Elephants have been an integral part of culture of the state. Kerala is home to the largest domesticated population of elephant in India—about 700 Indian elephants, owned by temples as well as individuals.[365] These elephants are mainly employed for the processions and displays associated with festivals celebrated all around the state. About 10,000 festivals are celebrated in the state annually and some animal lovers have sometimes raised concerns regarding the overwork of domesticated elephants.[318] In Malayalam literature, elephants are referred to as the 'sons of the sahya.[366] The elephant is the state animal of Kerala and is featured on the emblem of the Government of Kerala.[135]

Media

The media, telecommunications, broadcasting and cable services are regulated by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India. The National Family Health Survey – 3, conducted in 2007, ranked Kerala as a state with the highest media exposure in India. Dozens of newspapers are published in Kerala, in nine major languages,[367] but principally Malayalam and English.[368] Most widely circulating Malayalam-language newspapers are Malayala Manorama, Mathrubhumi, Madhyamam, Deshabhimani, Mangalam, Kerala Kaumudi, Chandrika, Thejas, Udaya keralam, Janayugam, Janmabhumi, Deepika and Siraj Daily. Major Malayalam periodicals include Mathrubhumi, India Today Malayalam, Madhyamam Weekly, Grihalakshmi, Vanitha, Dhanam, Chithrabhumi, and Bhashaposhini. The English reading population is slowly gaining strength in Kerala. The Hindu is the largest read newspaper in the State; followed by Deccan Chronicle, The New Indian Express and The Times of India.

Doordarshan is the state-owned television broadcaster. Multi system operators provide a mix of Malayalam, English and international channels via cable television. Some of the popular Malayalam television channels are Asianet, Surya TV, Kiran TV, Mazhavil Manorama, Manorama News, Indiavision, Kairali TV, Kairali WE, Kairali People, Yes Indiavision, Asianet News, Asianet Plus, Asianet Movies, Amrita TV, Reporter, Jaihind, Jeevan TV, Mathrubhumi News, Kaumudi, Shalom TV, Powervision, Goodness, Athmeyayathra and Media One TV. Television serials, reality shows and the Internet have become major sources of entertainment and information for the people of Kerala. A Malayalam version of Google News was launched in September 2008.[369] A sizeable "people's science" movement has taken root in the state, and such activities as writers' cooperatives are becoming increasingly common.[165][370]:2 BSNL, Reliance Infocomm, Airtel, Vodafone, Idea, Tata Docomo and Aircel are the major cell phone service providers in the state.[371] Broadband Internet services are widely available throughout the state; some of the major ISPs are BSNL, Asianet Satellite communications, Reliance Communications, Airtel and VSNL. According to the Telecom Regulatory Commission of India (TRAI) report, as of January 2012 the total number of wireless phone subscribers in Kerala is about 34.3 million and the wireline subscriber base is at 3.2 million, accounting for the telephone density of 107.77.[371] Unlike in many other States, the urban-rural divide is not visible in Kerala with respect to mobile phone penetration.[372]

Sports

By 21st century, almost all of the native sports and games from Kerala have either disappeared or become just an art form performed during local festivals; including Poorakkali, Padayani, Thalappandukali, Onathallu, Parichamuttukali, Velakali, Kilithattukali etc.[373] However, Kalaripayattu, regarded as "the mother of all martial arts in the world", as an exception was practised as indigenous martial sport.[374] Another traditional sport of Kerala is the boat race, especially the race of Snake boats.[373]

Cricket and football became popular in the state; both were introduced in Malabar during the British colonial period in the 19th century. Cricketers, like Tinu Yohannan,[375] and Abey Kuruvilla,[376] found places in the national cricket team. However, the Kerala cricket team had never won or performed well at the Ranji Trophy.[373] A cricket club from Kerala, the Kochi Tuskers, played in the Indian Premier League's third season. However, the team was disbanded after the season because of conflict of interests among its franchises.[377] Football is one of the most widely played and watched sport with huge support for club and district level matches.Kerala is one of the major footballing states in India along with West Bengal and Goa and has produced national players of the likes of I. M. Vijayan, C. V. Pappachan, V. P. Sathyan, and Jo Paul Ancheri.[378][379] The Kerala state football team had won the Santhosh Trophy five times; in 1973, 1992, 1993, 2001 and 2004. They were also the runner-ups for eight times.[380]

Among the prominent athletes hailing from the state, P. T. Usha, Shiny Wilson and M.D. Valsamma are both Padma Shri as well as Arjuna Award winners while K. M. Beenamol and Anju Bobby George are Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna as well as Arjuna Award winners. T. C. Yohannan, Suresh Babu, Sinimol Paulose, Angel Mary Joseph, Mercy Kuttan, K. Saramma, K. C. Rosakutty and Padmini Selvan are the other Arjuna Award winners from Kerala.[373][381] Volleyball is another popular sport[382] and is often played on makeshift courts on sandy beaches along the coast. Jimmy George was a notable Indian volleyball player, rated in his prime as among the world's ten best players.[383] Other popular sports include badminton, basketball and kabaddi.[384]

Tourism

Its culture and traditions, coupled with its varied demographics, have made Kerala one of the most popular tourist destinations in India. National Geographic's Traveller magazine names Kerala as one of the "ten paradises of the world"[385][386] and "50 must see destinations of a lifetime".[387] Travel and Leisure names Kerala as "One of the 100 great trips for the 21st century".[385][388][389] In 2012, it overtook Taj Mahal to be the number one travel destination in Google's search trends for India.[390] Kerala's beaches, backwaters, mountain ranges and wildlife sanctuaries are the major attractions for both domestic and international tourists. The city of Kochi ranks first in the total number of international and domestic tourists in Kerala.[391][392]

Until the early 1980s, Kerala was a relatively unknown destination to other states of the country.[393] In 1986 the government of Kerala declared tourism as an industry and it was the first state in India to do so.[394] Marketing campaigns launched by the Kerala Tourism Development Corporation, the government agency that oversees tourism prospects of the state, resulted in the growth of the tourism industry.[395] Many advertisements branded Kerala with a catchy tagline Kerala, God's Own Country.[395] Today, Kerala tourism is a global brand and regarded as one of the destinations with highest recall.[395] In 2006, Kerala attracted 8.5 million tourist arrivals, an increase of 23.68% over the previous year, making the state one of the fastest-growing destinations in the world.[396] In 2011, tourist inflow to Kerala crossed the 10-million mark.[397]

Ayurvedic tourism became very popular since the 1990s, and private agencies have played a notable role in tandem with the initiatives of Tourism Department.[393] Kerala is known for its ecotourism initiatives and in this segment it promotes mountaineering, trekking and bird-watching programmes in the Western Ghats as the major products.[398] As of 2005, the state's tourism industry was a major contributor to the state's economy, which is currently growing at a rate of 13.31%.[399] The revenue from tourism increased five-fold between 2001 and 2011 and crossed the ![]() 190 billion mark in 2011. Moreover, the industry provides employment opportunity to approximately 1.2 million people.[397]

190 billion mark in 2011. Moreover, the industry provides employment opportunity to approximately 1.2 million people.[397]

The most popular tourist attractions in the state are beaches, backwaters and hill stations. Major beaches are at Kovalam, Varkala, Fort Kochi, Cherai, Kappad, Muzhappilangad and Bekal. Popular hill stations are at Munnar, Wayanad, Wagamon, Peermade, Nelliampathi and Ponmudi.[400] Kerala's ecotourism destinations include 12 wildlife sanctuaries and two national parks: Periyar Tiger Reserve, Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Thattekad Bird Sanctuary, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary, Muthanga Wildlife Sanctuary, and Eravikulam National Park are the most popular among them.[401] The "backwaters" are an extensive network of interlocking rivers (41 west-flowing rivers), lakes, and canals that center around Alleppey, Kumarakom and Punnamada (where the annual Nehru Trophy Boat Race is held in August). Padmanabhapuram Palace and the Mattancherry Palace are two notable heritage sites. According to a survey conducted among foreign tourists, Elephants, fireworks display and huge crowd are the major attractions of Thrissur Pooram. Nemmara Vela is also famous for the fireworks.[402]

Major festivals and religious pilgrimage

- Sabarimala pilgrimage

- Manjinikkara Pilgrimage(Asia's largest pilgrimage on foot)

- Kottiyoor Vysakha Mahotsavam

- Thrissur Pooram

- Maramon Convention

- Attukal Pongala

- Thamarachal Ettunombu Fest

- Manarcad Fest

- Parumala Perunnal

See also

- Bibliography of India

- List of people from Kerala

- List of tallest buildings in Kerala

- Outline of Kerala

References

- ↑ News, Express. "Nikhil Kumar appointed Kerala Governor". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ↑ Census of India, 2011. Census Data Online, Population.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "India Human Development Report 2011: Towards Social Inclusion". Institute of Applied Manpower Research, Planning Commission, Government of India. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ http://ncrb.nic.in/CD-CII2011/cii-2011/Table%203.1.pdf

- ↑ "India Today On Cm". Keralacm.gov.in. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ↑ A. Sreedhara Menon (1987). Political History of Modern Kerala. D C Books. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-81-264-2156-5. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ Nicasio Silverio Sainz (1972). Cuba y la Casa de Austria. Ediciones Universal. p. 120. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ Robert Caldwell (1 December 1998). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages. Asian Educational Services. p. 92. ISBN 978-81-206-0117-8. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ John Ralston Marr (1985). The Eight Anthologies. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 263.

- ↑ Singh, Anees Jung ; illustrations by Prem (1993). Night of the new moon : encounters with Muslim women in India. New Delhi: Penguin Books. p. 100. ISBN 0140234055.

- ↑ Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–212. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ↑ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey Of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ M. T. Narayanan (1 January 2003). Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar. Northern Book Centre. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-81-7211-135-9. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ P. 204 Ancient Indian History By Madhavan Arjunan Pillai

- ↑ Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Goldberg, Ellen (2002). The Lord who is Half Woman: Ardhanārīśvara in Indian and Feminist Perspective. SUNY Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7914-5325-4.

- ↑ Kemmerer, Lisa (2011). Animals and World Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-991255-1.

- ↑ Dalal, Roshen (2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ Ragozin, Zenaide A. (2005). Vedic India As Embodied Principally in the Rig-veda. Kessinger Publishing. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-4179-4463-7. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ↑ "Literacy – official website of Govt. of Kerala". Retrieved 3 October 2011.(1st) The breakup shows 94.2 for males and 87.86 for females.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 A. Sreedhara Menon (2008). Cultural Heritage of Kerala. D C Books. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-81-264-1903-6.

- ↑ "Unlocking the secrets of history". The Hindu (Chennai, India). 6 December 2004.

- ↑ Subodh Kapoor (1 July 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 2184. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ Tourism information on districts –Wayanad, official website of the Govt. of Kerala

- ↑ Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 116. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. pp. 118, 123. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Symbols akin to Indus valley culture discovered in Kerala". The Hindu (Chennai, India). 29 September 2009.

- ↑ Striving for sustainability, environmental stress and democratic initiatives in Kerala, p. 79; ISBN 81-8069-294-9, Srikumar Chattopadhyay, Richard W. Franke; Year: 2006.