Kensington Runestone

| |

| Name | Kensington Runestone |

| Country | United States |

| Region | Minnesota |

| City/Village | Originally Kensington currently located at Alexandria, Minnesota |

| Produced | contested |

| Runemaster | contested |

Text - Native | |

|

direct transliteration[1] | |

| Text - English | |

|

(word-for-word):[1] | |

| Other resources | |

|

Runestones - Runic alphabet Runology - Runestone styles | |

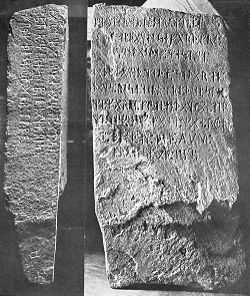

The Kensington Runestone is a 200-pound slab of greywacke covered in runes on its face and side, believed to have been created in modern times to claim that Scandinavian explorers reached the middle of North America in the 14th century. It was found in 1898 in the largely rural township of Solem, Douglas County, Minnesota, and named after the nearest settlement, Kensington. Almost all Runologists and experts in Scandinavian linguistics consider the runestone to be a hoax.[2][3] The runestone has been analyzed and dismissed repeatedly without altering local opinion of the Runestone's legitimacy.[4][5][6][7][8] The community of Kensington is solidly behind the runestone, which has transcended its asserted cultural importance to the Scandinavian community and has "taken on a life of its own".[9][10]

Provenance

Swedish immigrant[11] Olof Olsson Ohman asserted that he found the stone late in 1898 while clearing his land of trees and stumps before plowing, having recently taken over an 80-acre (320,000 m2) parcel of public domain land that had for years been left unallocated as "Internal Improvement Land".[12][13] The stone was said to be near the crest of a small knoll rising above the wetlands, lying face down and tangled in the root system of a stunted poplar tree, estimated to be from less than 10 to about 40 years old.[14] The artifact is about 30 × 16 × 6 inches (76 × 41 × 15 cm) in size and weighs about 200 pounds (90 kg). Ohman's ten-year-old son, Edward Ohman, noticed some markings,[15] and the farmer later said he thought they had found an "Indian almanac."

Unfortunately for provenance purposes, the only witnesses cited for the finding were family members, although people who later saw the cut roots said that some were flattened, consistent with having held a stone. Also, there are many versions describing when the stone was found (August or November, right after lunch or near the end of work for the evening), who discovered the stone (Olof Ohman and Edward Ohman; Olof Ohman, Edward Ohman and two workmen; Olof Ohman, Edward Ohman, and his neighbor Nils Flaten), when the stone was taken to the nearby town of Kensington, and who made the first transcriptions that were sent to a regional Scandinavian-language newspaper. Soon after it was found, the stone was displayed at a local bank. There is no evidence Ohman tried to make money from his find.[citation needed]

It can be claimed that at the period when Ohman discovered the stone, the journey of Leif Ericson to Vinland (North America) was being widely discussed and there was renewed interest in the Vikings throughout Scandinavia, stirred by the National Romanticism movement. Five years earlier Norway had participated in the World's Columbian Exposition by sending the Viking, a replica of the Gokstad ship to Chicago. There was also friction between Sweden and Norway (which ultimately led to Norway's independence from Sweden in 1905). Some Norwegians claimed the stone was a Swedish hoax and there were similar Swedish accusations because the stone references a joint expedition of Norwegians and Swedes at a time when they were ruled by the same king, after the Union of Kalmar. It is thought to be more than coincidental that the stone was found among Scandinavian newcomers in Minnesota, still struggling for acceptance and quite proud of their Nordic heritage.[16]

An error-ridden[citation needed] copy of the inscription made its way to the University of Minnesota. Olaus J. Breda (1853–1916), professor of Scandinavian Languages and Literature in the Scandinavian Department made a translation, declared the stone to be a forgery and published a discrediting article which appeared in Symra during 1910. Breda also forwarded copies of his translation to fellow linguists in Scandinavia. The Norwegian archeologist Oluf Rygh concluded the stone was a fraud, as did several other noted linguists.[17]

The stone was then sent to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Scholars either dismissed it as a prank or felt unable to identify a sustainable historical context. The stone was returned to Ohman, who is said to have placed it face down near the door of his granary as a "stepping stone" which he also used for straightening out nails. Years later, his son said this was an "untruth" and that they had it set up in an adjacent shed, but he appears to have been referring only to the way the stone was treated before it started to attract interest at the end of 1898.

In 1907 the stone was purchased, reportedly for ten dollars, by Hjalmar Holand, a former graduate student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Holand renewed public interest with an article[18] enthusiastically summarizing studies that were made by geologist Newton Horace Winchell (Minnesota Historical Society) and linguist George T. Flom (Philological Society of the University of Illinois), who both published opinions in 1910.[19]

According to Winchell, the tree under which the stone was allegedly found had been destroyed before 1910. Several nearby poplars that witnesses estimated as being about the same size were cut down and, by counting their rings, it was determined they were around 30–40 years old. One member of the team who had excavated at the find site in 1899, county schools superintendent Cleve Van Dyke, later recalled the trees being only ten or twelve years old.[20] The surrounding county had not been settled until 1858, and settlement was severely restricted for a time by the Dakota War of 1862 (although it was reported that the best land in the township adjacent to Solem, Holmes City, was already taken by 1867, by a mixture of Swedish, Norwegian and "Yankee" settlers.[21])

Winchell concluded that the weathering of the stone indicated the inscription was roughly 500 years old. Meanwhile, Flom found a strong apparent divergence between the runes used in the Kensington inscription and those in use during the 14th century. Similarly, the language of the inscription was modern compared to the Nordic languages of the 14th century.[19]

The Kensington Runestone is on display at the Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota.[22]

Possible historical background

In 1577, cartographer Gerardus Mercator wrote a letter containing the only detailed description of the contents of a geographical text about the Arctic region of the Atlantic, possibly written over two centuries earlier by one Jacob Cnoyen. Cnoyen had learned that in 1364, eight men had returned to Norway from the Arctic islands, one of whom, a priest, provided the King of Norway with a great deal of geographical information.[23] Books by scholars such as Carl Christian Rafn early in the 19th century revealed hints of reality behind this tale. A priest named Ivar Bardarsson, who had previously been based in Greenland, did turn up in Norwegian records from 1364 onward and copies of his geographical description of Greenland still survive. Furthermore, in 1354, King Magnus Eriksson of Sweden and Norway had issued a letter appointing a law officer named Paul Knutsson as leader of an expedition to the colony of Greenland, to investigate reports that the population was turning away from Christian culture.[24] Another of the documents reprinted by the 19th century scholars was a scholarly attempt by Icelandic Bishop Gisli Oddsson, in 1637, to compile a history of the Arctic colonies. He dated the Greenlanders' fall away from Christianity to 1342, and claimed that they had turned instead to America. Supporters of a 14th-century origin for the Kensington runestone argue that Knutson may therefore have travelled beyond Greenland to North America, in search of renegade Greenlanders, most of his expedition being killed in Minnesota and leaving just the eight voyagers to return to Norway.[25]

However, there is no evidence that the Knutson expedition ever set sail (the government of Norway went through considerable turmoil in 1355) and the information from Cnoyen as relayed by Mercator states specifically that the eight men who came to Norway in 1364 were not survivors of a recent expedition, but descended from the colonists who had settled the distant lands, generations earlier.[23] Also, those early 19th century books, which aroused a great deal of interest among Scandinavian Americans would have been available to a late 19th-century hoaxer.

Hjalmar Holand had proposed that interbreeding with Norse survivors might explain the "blond" Indians among the Mandan on the Upper Missouri River,[26] but in a multidisciplinary study of the stone, anthropologist Alice Beck Kehoe dismissed, as "tangential" to the Runestone issue, this and other historical references suggesting pre-Columbian contacts with 'outsiders', such as the Hochunk (Winnebago) story about an ancestral hero "Red Horn" and his encounter with "red-haired giants".[27]

Geography

A natural north-south navigation route—admittedly with a number of portages round dangerous rapids—extends from Hudson Bay up Nelson River (or the Hayes River, as preferred by early modern traders from York Factory[28][29]) through Lake Winnipeg, then up the Red River of the North. The northern waterway begins at Traverse Gap, on the other side of which is the source of the Minnesota River, flowing to join the great Mississippi River at Saint Paul/Minneapolis. One of the early Runestone debunkers, George Flom, found that explorers and traders had come from Hudson Bay to Minnesota by this route decades before the area was officially settled.[30] Supporters of the stone's authenticity argued that the 1362 party could have used the same waterway.[31] This idea is based on Scandinavian voyagers sailing the rivers from the Baltic sea down to Istanbul during the Viking age, but this ignores that different ship types were used to cross oceans and to sail on rivers. The boats that are small enough for portage are not suitable for open sea voyages.[32]

Other artifacts?

This waterway contains alleged signs of Viking presence. At Cormorant Lake in Becker County, Minnesota, there are three boulders with triangular holes which are claimed to be similar to those used for mooring boats along the coast of Norway during the 14th century. Holand found other triangular holes in rocks near where the stone was found; however, experimental archaeology later suggested that holes dug in stone with chisels rather than drills tend to have a triangular cross-section, whatever their purpose.[33] A little further north, by the Red River itself, at Climax, Minnesota, a firesteel found in 1871, buried quite deep in soft ground, matched specimens of medieval Norse firesteels at the Oslo University museum in Norway.[34]

There has been considerable discussion of what has recently been named the Vérendrye Runestone, a small plaque allegedly found by one of the earliest expeditions along what later became the U.S./Canada border, in the 1730s. "Allegedly", because it is not referred to in the journal of the expedition or, indeed, any first-hand source: only in a summary of a conversation about the expedition a decade later.[35]

No non-Native American artifacts dating from before 1492 have been recovered under controlled, professionally conducted archaeological investigations at any great distance from the east coast of the continent; with current techniques, the dating of any holes cut into rocks in the region is as uncertain as the dating of the Kensington stone itself.

Text

This is a transliteration of the stone:[1]

| “ |

8 : göter : ok : 22 : norrmen : po : |

” |

The lateral (or side) text reads:[1]

| “ |

här : (10) : mans : ve : havet : at : se : |

” |

Translation:[1]

Eight Götalanders and 22 Northmen on (this?) acquisition journey from Vinland far to the west. We had a camp by two (shelters?) one day's journey north from this stone. We were fishing one day. After we came home, found 10 men red from blood and dead. Ave Maria save from evil. There are 10 men by the inland sea to look after our ships fourteen days journey from this peninsula (or island). Year 1362

When the original text is transcribed to the Latin script, the message becomes quite easy to read for any modern Scandinavian. This fact is one of the main arguments against the authenticity of the stone. The language of the inscription bears much closer resemblance to 19th-century than 14th-century Swedish.[4]

The AVM is historically consistent since any Scandinavian explorers would have been Catholic at that time.

Debate

Holand took the stone to Europe and, while newspapers in Minnesota carried articles hotly debating its authenticity, the stone was quickly dismissed by Swedish linguists.

For the next 40 years, Holand struggled to sway public and scholarly opinion about the Runestone, writing articles and several books. He achieved brief success in 1949, when the stone was put on display at the Smithsonian Institution, and scholars such as William Thalbitzer and S. N. Hagen published papers supporting its authenticity.[36] However, at nearly the same time, Scandinavian linguists Sven Jansson, Erik Moltke, Harry Anderson and K. M. Nielsen, along with a popular book by Erik Wahlgren again questioned the Runestone's authenticity.[4]

Along with Wahlgren, historian Theodore C. Blegen flatly asserted[5] Ohman had carved the artifact as a prank, possibly with help from others in the Kensington area. Further resolution seemed to come with the 1976 published transcript[6] of an interview of Frank Walter Gran conducted by Dr. Paul Carson, Jr. on August 13, 1967 that had been recorded to audio tape.[37][38] In it, Gran said his father John confessed in 1927 that Ohman made the inscription. John Gran's story however was based on second-hand anecdotes he had heard about Ohman, and although it was presented as a dying declaration, Gran lived for several years afterwards saying nothing more about the stone. In 2005 supporters of the runestone's authenticity attempted to explain this with claims that Gran was motivated by jealousy over the attention Ohman had received.

The possibility of a Scandinavian provenance for the Runestone was renewed in 1982 when Robert Hall, an emeritus Professor of Italian Language and Literature at Cornell University published a book (and a follow up in 1994) questioning the methodology of its critics. He asserted that the odd philological problems in the Runestone could be the result of normal dialectal variances in Old Swedish during the purported carving of the Runestone. Further, he contended that critics had failed to consider the physical evidence, which he found leaning heavily in favour of authenticity. Meanwhile in The Vikings and America (1986) former UCLA professor Erik Wahlgren wrote that the text bore linguistic abnormalities and spellings that he thought suggested the Runestone was a forgery.[8]

Opthagelsefarth: Richard Nielsen and others

As an example of how linguistic research affects the discussion of this text, no evidence has been found of the Swedish term opthagelse farth (journey of discovery), or updagelsefard as it often appears, in Old Swedish, Danish or Norwegian, nor in Middle Dutch or Middle Low German during the 14th or 15th centuries.[39]

In the contemporary and modern Scandinavian languages the term is called opdagelsesrejse in Danish, oppdagingsferd or oppdagelsesferd in Norwegian and upptäcktsfärd in Swedish. It is considered a fact that the modern word is a loan-translation from Low German *updagen, Dutch opdagen and German aufdecken, which are in turn loan-translations of French découvrir.

In a conversation with Holand in 1911, the lexicographer of the Old Swedish Dictionary (Soderwall) noted that his work was limited mostly to surviving legal documents written in formal and stilted language and that the root word opdage must have been a borrowed Germanic term (i.e. from Low German, Dutch or High German). Also, the -else ending characterizes a class of words that the Scandinavians borrowed from their southern neighbors.

However, before the Scandinavians could have borrowed the term from the West Germanic languages, West Germanic language speakers had to have first borrowed it from the French language, which did not happen before the 16th century. Linguists who, due to this and similar facts, reject the Medieval origin of the Kensington inscription, consider this word to be a neologism and have noted that, in a Norwegian newspaper circulated in Minnesota, the late 19th-century Norwegian historian Gustav Storm often used this term in articles on Viking exploration.

Nielsen suggests that the Þ (transliterated above as th or d) could also be a t sound, which would mean the word could be the 14th century expression uptagelsefart (acquisition expedition). However, in the rest of the text, the Thorn rune regularly corresponds to modern Scandinavian d-sounds and only occasionally to historical th-sounds, while the T-rune is used for all other t-sounds.

More linguistic problems

Another characteristic pointed out by skeptics is the text's lack of cases. Old Norse had four cases, preserved in modern Icelandic, Faroese and arguably Elfdalian. They had disappeared from common speech by the 16th century but were still predominant in the 14th century (see Swedish language). Also, the text does not use the plural verb forms that were common in the 14th century and have only recently disappeared: for example, (plural forms in parenthesis) "wi war" (wörum), "hathe" (höfuðum), "[wi] fiske" (fiskaðum), "kom" (komum), "fann" (funnum) and "wi hathe" (hafdum). Proponents of the stone's authenticity point to sporadic examples of these simpler forms in some 14th-century texts and to the great changes of the morphological system of the Scandinavian languages that began during the latter part of that century.[40]

The inscription also contains "pentadic" numerals. Such numerals are known in Scandinavia, but nearly always from relatively recent times, not from verified medieval runic monuments, on which numbers were usually spelled out as words. For example, to write EINN (one) the runes E-I-N were used (writing customs avoided having the same rune twice in a row for identical sounds) and indeed the word EN (one) is in the Kensington inscription. Writing all the numbers out (such as thirteen hundred and sixty-two) would not have easily fit the surface space, so the stone's author (whether a forger or 14th-century explorer) simplified things by using pentadic runes as numerals in the Indo-Arabic positional numbering system. This system had been described in an early 14th-century Icelandic book called Hauksbók, known to have been taken to Norway by its compiler Haukr Erlendsson. However, the few pages of Hauksbók, called Algorismus, that describe the Indo-Arabic numerals and how to use them in calculations, are believed not to have been widely known at the time, and that the Indo-Arabic number system did not become widespread in Scandinavia until centuries later.

It must be admitted, however, that these points are "arguing from silence", and that 14th century Scandinavia was hardly isolated from current European thought and movements of the period.

AVM: A medieval abbreviation?

In 2004, Keith Massey and Kevin Massey published their theory that the Latin letters on the Kensington Stone, AVM, contain evidence authenticating a medieval date for the artifact.[41] The Kensington Stone critic Erik Wahlgren had noticed that the carver had incised a notch on the upper right hand corner of the letter V.[4] The Massey Twins note that a mark in that position is consistent with an abbreviation technique used in the 14th century. To render the word "Ave" in that period, the final vowel would have been written as a superscript. Eventually, the superscript vowel was replaced by a mere superscript dot. The existence of a notch where Wahlgren notes, then, shows that the carver was familiar with 14th century abbreviation techniques. The Massey Twins, however, point out that knowledge of these conventions was not available to the purported forger in late 19th century Minnesota, as books documenting these techniques were being printed in Italian academic circles only a few years after Ohman discovered the stone.[citation needed] It is possible, however, that Ohman or someone else had observed such a device on a medieval artefact before moving to the United States.

Rune statistics

The Kensington inscription consists of 29 different runic characters. Of these, 18 belong to the normal futhark series, q.e. a, b, d(/th), e, f, g, h, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, and v. Then there are three special umlauted runes, that are marked by two dots above them. These represent the letters ü, ä and ö. There is also one appearance of the Arlaug rune which usually represents the number 17. This does not work on the Kensington Stone, so therefore it's sometimes interpreted as a bind rune of e and l. Finally, there are seven others that represent the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10. These results are obtained by counting how many times each rune recurs on the stone. Since the included photographs of the stone are quite sharp, the reader can easily verify this. Furthermore, it is also quite easy to see what Latin letter each rune represents, since most of the words are readily recognized as modern Swedish words. The result of such analysis also agrees nicely with the runic alphabets recorded by Edward Larsson in 1885.

Edward Larsson's notes

Many runes in the inscription deviate from known medieval runes, but in 2004 it was discovered that these appear along with pentadic runes in the 1883 notes of a 16-year-old journeyman tailor with an interest in folk music, Edward Larsson.[42] A copy was published by the Institute for Dialectology, Onomastics and Folklore Research in Umeå, Sweden and while an accompanying article suggested the runes were a secret cipher used by the tailors' guild, no usage of futharks by any 19th-century guild has been documented. However, given that the Larsson notes are the only firm evidence for 19th century knowledge of these futharks, it does appear that a secret has been kept with considerable success. The notes also include the Pigpen cipher, devised by the Freemasons, and it may not be coincidental that the abbreviation AVM seen in Latin letters on the Kensington stone also appears (for AUM) on many Masonic gravestones; Wolter and Nielsen in their 2005 book even suggested a connection with the Knights Templar.

Larsson's notes disprove the early theory that the unusual runes on the Kensington Runestone were invented on the spot by the supposed 1890s hoaxer; but without a source for Larsson's rune rows (for example an ancient book, or records from the hypothetical Masonic-type organisation), it is not possible to give their origin any particular date range closer than "before 1883." However, his second rune row includes runes for the letters Å, Ä and Ö, which were introduced into the Swedish version of the Latin alphabet in the 16th century.[43] Although Nielsen has demonstrated that double-dotted runes were used in medieval inscriptions to indicate lengthened vowels[citation needed], the presence of other letters from the second Larsson rune row on the Kensington stone can be interpreted as suggesting that the post-16th century versions were intended in this case.

In December 2012, a Norwegian TV documentary revealed that Larsson's aunt had migrated with her husband and son from Sweden to Crooked Lake, just outside Alexandria, in 1870.[44]

The stone and the Larsson runes

Before Edward Larsson's sheet of runic alphabets surfaced in Sweden in 2004, when the stone was exhibited there, it seemed as if the Kensington runes were gathered from many different futharks, or in a few cases invented by the carver. Larsson's sheet lists two different Futharks. The first Futhark consists of 22 runes, the last two of which are bind-runes, representing the letter-combinations EL and MW. His second Futhark consists of 27 runes, where the last 3 are specially adapted to represent the letters å, ä, and ö of the modern Swedish alphabet.[42]

Comparing the Kensington Futhark with Larsson's two it appears to some that the Kensington runes can be interpreted as a selective combination of Larsson's two Futharks, with some very minor variations such as mirror-imaging. On the stone the runes representing e, g, n, and i can be argued to have been taken from Larsson's first Futhark, and likewise the runes representing the letters a, b, k, u, v, ä, and ö from Larsson's second Futhark.

However, the use of runes in the medieval period is far from systematic or coherent: in defence of the possibility of the genuineness of the stone, S.N. Hagen had earlier written: "The Kensington alphabet is a synthesis of older unsimplified runes, later dotted runes, and a number of Latin letters ... The runes for a, n, s and t are the old Danish unsimplified forms which should have been out of use for a long time [by the 14th century]...I suggest that [a posited 14th century] creator must at some time or other in his life have been familiar with an inscription (or inscriptions) composed at a time when these unsimplified forms were still in use" and that he "was not a professional runic scribe before he left his homeland".[45]

See also

- AVM Runestone, a hoax planted near the site of the Kensington runestone

- Beardmore Relics, Viking Age relics, supposedly found in Canada, associated with the Kensington runestone

- Elbow Lake Runestone, a hoax planted in Minnesota

- Heavener Runestone, a runestone found in Oklahoma

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Richard Nielsen and Henrik Williams (May 2010). "Inscription Translation". Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ "forskning.no Kan du stole på Wikipedia?" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2008-12-19. "Det finnes en liten klikk med amerikanere som sverger til at steinen er ekte. De er stort sett skandinaviskættede realister uten peiling på språk, og de har store skarer med tilhengere." Translation: "There is a small clique of Americans who swear to the stone's authenticity. They are mainly natural scientists of Scandinavian descent with no knowledge of linguistics, and they have large numbers of adherents."

- ↑ Gustavson, Helmer. "The non-enigmatic runes of the Kensington stone". Viking Heritage Magazine (Gotland University) 2004 (3). "[...] every Scandinavian runologist and expert in Scandinavian historical linguistics has declared the Kensington stone a hoax [...]"

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Wahlgren, Erik (1958). The Kensington Stone, A Mystery Solved. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 1-125-20295-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Blegen, T (1960). The Kensington Rune Stone : New Light on an Old Riddle. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-044-5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fridley, R (1976). "The case of the Gran tapes". Minnesota History 45 (4): 152–156.

- ↑ Wallace, B (1971). "Some points of controversy". In Ashe G et al.. The Quest for America. New York: Praeger. pp. 154–174. ISBN 0-269-02787-4.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wahlgren, Erik (1986). The Vikings and America (Ancient Peoples and Places) (in Wahlgren1986). Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-02109-0.

- ↑ Michlovic MG (1990). "Folk Archaeology in Anthropological Perspective". Current Anthropology 31 (11): 103–107. doi:10.1086/203813.

- ↑ Hughey M, Michlovic MG (1989). "Making history: The Vikings in the American heartland". Politics, Culture and Society 2 (3): 338–360. doi:10.1007/BF01384829.

- ↑ http://kahsoc.org/ohman.htm farmer

- ↑ "Extract from 1886 plat map of Solem township". Archived from the original on 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ↑ Stephen Minicucci, Internal Improvements and the Union, 1790–1860, Studies in American Political Development (2004), 18: p.160-185, (2004), Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/S0898588X04000094. "Federal appropriations for internal improvements amounted to $119.8 million between 1790 and 1860. The bulk of this amount, $77.2 million, was distributed to the states through indirect methods, such as land grants or distributions of land sale revenues, which would today be labeled "off-budget.""

- ↑ "Done in Runes". Minneapolis Journal (appendix to "The Kensington Rune Stone" by T. Blegen, 1968). 22 February 1899. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ↑ Hall Jr., Robert A.: The Kensington Rune-Stone Authentic and Important, page 3. Jupiter Press, 1994.

- ↑ Michael G. Michlovic, "Folk Archaeology in Anthropological Perspective" Current Anthropology 31.1 (February 1990:103–107) p. 105ff.

- ↑ Olaus J. Breda. Rundt Kensington-stenen, (Symra. 1910, pp. 65–80)

- ↑ Holand, "First authoritative investigation of oldest document in America", Journal of American History 3 (1910:165–84); Michlovic noted Holand's contrast of the Scandinavians as undaunted, brave, daring, faithful and intrepid contrasted with the Indians as savages, wild heathens, pillagers, vengeful, like wild beasts: an interpretation that "placed it squarely within the framework of Indian-white relations in Minnesota at the time of its discovery." (Michlovic 1990:106).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Winchell NH, Flom G (1910). "The Kensington Rune Stone: Preliminary Report". Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society 15. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ↑ Milo M. Quaife, "The myth of the Kensington runestone: The Norse discovery of Minnesota 1362" in The New England Quarterly December 1934

- ↑ Lobeck, Engebret P. (1867). "Holmes City narrative on Trysil (Norway) emigrants website (via Archive.org)". Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "Kensington Runestone Museum, Alexandria Minnesota". Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Taylor, E.G.R. (1956). "A Letter Dated 1577 from Mercator to John Dee". Imago Mundi 13: 56–68. doi:10.1080/03085695608592127.

- ↑ Full text in Diplomatarium Norvegicum English translation

- ↑ Holand, Hjalmar (1959). "An English scientist in America 130 years before Columbus". Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy 48: 205–219ff.

- ↑ Hjalmar Holand, "The Kensington Rune Stone: A Study in Pre-Columbian American History." Ephraim WI, self-published (1932).

- ↑ Alice Beck Kehoe, The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically, Long Grove IL, Waveland Press (2004) ISBN 1-57766-371-3. Chapter 6.

- ↑ The Grass River at Great Canadian Rivers

- ↑ Harry B. Brehaut & P. Eng The Red River Cart and Trails in Transactions of the Manitoba Historical Society, series 3 no. 28 (1971–2)

- ↑ Flom, George T. "The Kensington Rune-Stone" Springfield IL, Illinois State Historical Soc. (1910) p37

- ↑ Pohl, Frederick J. "Atlantic Crossings before Columbus" New York, W.W. Norton & Co. (1961) p212

- ↑ Sören Gannholm. "Ship models". Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ↑ Powell, Bernard W. (1958). "The Mooring Hole Problem in Long Island Sound". Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 19 (2): 31.

- ↑ Holand, Hjalmar (1937). "The Climax Fire Steel". Minnesota History 18: 188–190.

- ↑ Kalm, Pehr (1748). "Travels into North America (vol. 2, pages 279–81)". Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Olof Ohman's Runes". TIME. 8 October 1951. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ Nielsen, Richard & Wolter, Scott F. "The Kensington Rune Stone: Compelling New Evidence" Lake Superior Agate Publishing (June 2005) ISBN 1-58175-562-7

- ↑ American heritage August 1977

- ↑ Williams, Henrik (2012). "The Kensington Runestone: Fact and Fiction". The Swedish-American Historical Quarterly 63 (1): 3–22.

- ↑ John D. Bengtson. "The Kensington Rune Stone: A Study Guide". jdbengt.net. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ Keith and Kevin Massey, "Authentic Medieval Elements in the Kensington Stone" in Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications Vol. 24 2004, pp 176–182

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Tryggve Sköld (2003). "Edward Larssons alfabet och Kensingtonstenens" (PDF). DAUM-katta (in (Swedish)) (Umeå: Dialekt-, ortnamns- och folkminnesarkivet i Umeå) (Winter 2003): 7–11. ISSN 1401-548X. Retrieved 06-02-2009.

- ↑ unilang.org on the Swedish alphabet

- ↑ "Kensingtonsteinens gåte" (in Norwegian). Schrödingers katt. Episode subtitles (click "Teksting"). 2012-12-20. NRK.

- ↑ Article The Kensington Runic Inscription by S.N. Hagen, in: Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, Vol. XXV, No.3, July 1950.

Literature

- Thalbitzer, William C. (1951). Two runic stones, from Greenland and Minnesota. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 2585531.

- Hall, Robert A., Jr. (1982). The Kensington Rune-stone is Genuine: Linguistic, practical, methodological considerations. Columbia, SC: Hornbeam Press. ISBN 0-917496-21-3.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck (2005). The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically. Waveland Press. ISBN 1-57766-371-3.

- "Kensingtonstenens gåta – The riddle of the Kensington runestone" (PDF). Historiska nyheter (in (Swedish) and (English)) (Stockholm: Statens historiska museum) (Specialnummer om Kensingtonstenen): 16 pages. 2003. ISSN 0280-4115. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Anderson, Rasmus B (1920). "Another View of the Kensington Rune Stone". Wisconsin Magazine of History 3: 1–9. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- Flom, George T (1910). "The Kensington Rune-Stone: A modern inscription from Douglas County, Minnesota". Publications of the Illinois State Historical Library (Illinois State Historical Society) 15: 3–44. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kensington Runestone. |

- Kensington Runestone Park in Solem Township, Douglas County, Minnesota

- Runestone Museum which houses the stone in Alexandria, Minnesota

- 360 View of Rune Stone Zoom into and view the stone just like you were at the museum.

Coordinates: 45°48.788′N 95°40.305′W / 45.813133°N 95.671750°W