Kechewaishke

| Kechewaishke (Great Buffalo) | |

|---|---|

Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society | |

| Born |

c.1759 La Pointe, Madeline Island, Lake Superior |

| Died |

September 7, 1855 La Pointe |

| Nationality | Ojibwe |

| Other names | Bizhiki (Buffalo) |

Chief Buffalo (Ojibwe: Ke-che-waish-ke/Gichi-weshkiinh – "Great-renewer" or Peezhickee/Bizhiki – "Buffalo"; also French, Le Boeuf) (1759?-September 7, 1855) was an Ojibwa leader born at La Pointe in the Apostle Islands group of Lake Superior, in what is now northern Wisconsin, USA. Recognized as the principal chief of the Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwa)[1] for nearly a half-century until his death in 1855, he led his nation into a treaty relationship with the United States Government signing treaties in 1825, 1826, 1837, 1842, 1847, and 1854. He was also instrumental in resisting the efforts of the United States to remove the Chippewa and in securing permanent reservations for his people near Lake Superior.

Background

Political Structure of the Lake Superior Ojibwa

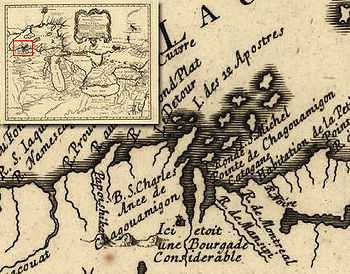

Kechewaishke was born around the year 1759 at La Pointe on Madeline Island (Mooningwanekaaning) in the Shagawamikong region. Now part of Wisconsin, La Pointe was a key Ojibwa village and trading center for the empire of New France, which was engaged in the Seven Years' War at the time of Buffalo's birth.[2] Throughout the 18th century, the Ojibwa spread out from La Pointe into lands conquered from the Dakota people, and settled several village sites. Still, these bands in the western Lake Superior and Mississippi River regions regarded La Pointe as their "ancient capital" and center for trade and spirituality.[3]

Traditional Ojibwa government and society centers around clans symbolized by animal doodem.[4] Each doodem had a designated task, and Buffalo's family, the Loons,[5] were rising in prominence in the middle of the 18th-century due to the efforts of his grandfather Andaigweos (Ojibwe: Aandegwiiyaas, "Crow's Meat"). Andaigweos was born in the Shagawamikong region, a son to a man described as "a Canadian Indian" (i.e. a Saulteaux from Sault Ste. Marie, a key Ojibwa village at the eastern end of Lake Superior). At the time of first French contact in the mid-17th century, the Crane doodem held the position of hereditary peace chiefs at both Sault Ste. Marie and La Pointe. Andaigweos, recorded as being a kind and widely-respected man who lived to an old age, was a skilled orator and favorite of the French officials and voyageurs, in contrast to the Cranes whose leading members at this time were more soft-spoken and concerned with internal matters. By the 19th century, it was Buffalo's family the Loons rather than the Cranes, who were recognized as principal chiefs at La Pointe.[6][7]

Although the Loons were afforded the respect as principal peace chiefs, this status was by no means permanent. The Cranes, led in Buffalo's time by his sub-chief Tagwagane, still maintained that they were the hereditary chiefs and that the Loons status as spokesmen hinged upon recognition by the Cranes. Regardless, a chief's power in Ojibwa society was based on persuasion, and held only as long as the community of elders chose to respect and follow his lead and was by no means absolute or binding.[8]

Personal life

Sources conflict on the identity of Buffalo's father, who may have also been named Andaigweos. He also appears to have been a descendant or relative of the famous war chief Waubojeeg.[9] When he was about 10, Buffalo and his parents moved from La Pointe to the vicinity of what now is Buffalo, New York, and lived there until about he was about 12. The family then relocated to Mackinaw area for a while before returning to La Pointe. In his youth, he was admired as a skilled hunter and athlete.[10]

Like many Anishinaabe people, Buffalo was known by more than one Ojibwe name: Peshickee (Bizhiki: "the Buffalo"), and Kechewaishke (Gichi-weshkiinh: "the Great-renewer"). This has caused a great deal of identity confusion in records of his life not only because he carried two names, but also because both names were very similar to those of other prominent contemporaries. Bizhiki was the name of a chief from the St. Croix Band, and also of a warrior of the Pillager Chippewa Band (see Beshekee). Additionally, a leading individual of the Caribou doodem, and a son of Waubojeeg, in the Sault Ste. Marie area was known by the name of Waishikey (Weshki). Scholars have mistakenly attributed aspects of the lives of all three of these individuals to Buffalo of La Pointe.[11]

In his long life, he had five wives and numerous children, many of whom became prominent Ojibwa leaders in the reservation era. He practiced the Midewiwin religion, though he converted to Roman Catholicism on his death bed.[12]

Views on International Relations

When Tecumseh's War broke out, Buffalo and a number of other young warriors from the La Pointe area abandoned the Midewiwin for a time to follow the teachings of the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa. While en route to Prophetstown to join the attack on the Americans, however, they were stopped by Michel Cadotte, the respected Métis fur trader from La Pointe. Cadotte managed to convince Buffalo and the others that it would be fruitless to fight the Americans.[13]

Details on Buffalo's early life are sparse. Although he appears to have been favored by British traders and decorated by British authorities,[16] very few Ojibwa from Lake Superior fought in either the American Revolution or the War of 1812, and there is no record of Buffalo participating.

Buffalo inherited not only the status afforded his family, but also many of these skills praised in his grandfather Andaigweos, and though Buffalo was noted for his abilities in hunting and battle, it was through his speaking abilities that he became recognized as chief. By the time the Ojibwa of Wisconsin and Minnesota started treaty negotiations with the US Government, Buffalo was recognized as one of the primary spokesmen for all the bands, not just for the Ojibwa from La Pointe.

Treaties of 1825 and 1826

A year later, the Treaty of Fond du Lac was signed at the western edge of Lake Superior. The signatories were listed by band, and Buffalo, recorded as Peezhickee, signed as the first chief from La Pointe. The treaty, mainly dealing with mineral rights Ojibwa lands in what is now Michigan, had little immediate impact, but foreshadowed future treaties. Buffalo did not speak on the copper issue, but he did praise the government officials for their ability to keep their young people under their control and asked for whiskey to accomplish the same ends among the younger members of his band. When the agent presented him with a silver medal symbolizing his chieftainship, he explained that his power stemmed from his family and reputation and not from anything received from the U.S. Government.[19]

Shortly after the treaties, Henry Schoolcraft, acting in his capacity as Indian agent, visited La Pointe and reprimanded Buffalo for not stopping the continuing sporadic warfare between the Ojibwa and Dakota. Buffalo replied that he was unable to stop the young men of Lac Courte Oreilles, St. Croix, Lac du Flambeau or other bands beyond La Pointe from going against the Dakota, demonstrating that while regarded as the head spokesman of the Ojibwa in Wisconsin, he could not control the day-to-day affairs of all the bands. He also remarked that unlike the British had before the War of 1812, the U.S. Government had not done enough in maintaining the peace.[20]

Treaties of 1837 and 1842

In the next decades, with whites eyeing the mineral and timber resources of Ojibwa country, the US government once again sought to acquire control of the territory through treaties. The Treaties of 1837 and 1842 covered La Pointe and the territories held by other bands over which Buffalo held considerable influence. In both treaties, Americans recognized Buffalo's position as the principal chief of all the Lake Superior Chippewa.

The "Pine Tree" Treaty

In the Treaty of St. Peters (1837), the government sought the pine timber resources on Ojibwa lands, floating the harvested timber southwest into the Mississippi River. The negotiations took place at Fort Snelling, near present-day Minneapolis and naturally the delegations from Minnesota and the St. Croix area arrived first and began discussions on July 20. Nevertheless, Buffalo's word was needed before any of assembled chiefs would consider the treaty. Despite the impatience of the territorial governor, Henry Dodge, the negotiations were delayed for five days as the assembled bands waited for Buffalo to arrive. While other chiefs spoke on the terms of mineral rights and annuity amounts, Buffalo spoke on behalf of the mixed-blood traders, stating:

I am an Indian and do not know the value of money, but the half-breeds do, for which reason we wish you pay them their share in money. You have good judgment in what you do, and if you do not act yourself, you will appoint someone else to divide it between the half breeds. ...I have good reasons for saying to you what I have just said; for at a certain Treaty held heretofore, there were some who got rich while others received nothing.[21]

Once the terms were agreed to, Buffalo marked and was recorded as Pe-zhe-ke, head of the La Pointe delegation. Although, Buffalo and the other Lake Superior chiefs signed, there is evidence that their relative silence compared with the Mississippi Chippewa chiefs during the negotiations symbolized disagreement rather than acceptance to the terms of the treaty. Lyman Warren, a trader and interpreter from La Pointe, later complained that the Pillagers (bands from present-day Minnesota) had been bribed into selling the lands rightfully belonging to the Wisconsin bands.[22]

Buffalo himself expressed his misgivings over the circumstances of the treaty in a letter to Dodge stating, "The Indians acted like children; they tried to cheat each other and got cheated themselves. When it comes my turn to sell my land, I do not think I shall give it up as they did." He went on to say in regards to possible future cessions of the Lake Superior shore: "Father I speak for my people, not for myself. I am an old man. My fire is almost out—there is but little smoke. When I sit in my wigwam & smoke my pipe, I think of what has past and what is to come, and it makes my heart shake. When business comes before us, we will try and act like Chiefs. If any thing is to be done, it had better be done straight."[23]

The "Copper" Treaty

Five years later, Buffalo was presented with the Treaty of La Pointe covering his lands. Acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs Henry Stuart, who was actively promoting the development of the Lake Superior copper industry, led the negotiations for the government. Unlike the 1837 Treaty, no record of the negotiations was made. However, materials written by missionaries, traders, and the Ojibwa themselves through their agent indicated that Stuart used bullying and outright deception to force the Ojibwa to accept the terms.[24]

Buffalo signed and was recorded as Gichi waishkey, 1st chief of La Pointe. Writing in 1855, Morse describes Buffalo's "voice so potent at the treaty of '42."[25] However, three months after the treaty, he dictated a letter to the government in Washington D.C. stating he was "ashamed" by the way the treaty was conducted, that Stuart had refused to listen to any objections by the Ojibwa, and that he wished to add a provision for permanent reservations in Wisconsin.[26]

The exact nature of 1837 and 1842 treaties remained ambiguous, with the government claiming the Ojibwa ceded title to the lands and the Ojibwa claiming they only ceded resource rights, the government having made the point several times that the lands of the Ojibwa were unsuitable for farming and white settlement. However, the Ojibwa did obtain annuity payments to be paid each year at La Pointe and reserved the right to hunt, fish, gather, and move across any lands outlined in the treaties. Furthermore, they obtained the promise that the nation would not be removed across the Mississippi River unless they somehow "misbehaved."[27]

Threats of Removal

Back in 1830, President Andrew Jackson had signed the Indian Removal Act, which enabled the United States to move any Indian nations east of the Mississippi River across to the western side. However, with northern Wisconsin not being highly desired by white settlers, the Ojibwa were not among the first targets for the act. They watched closely as the government used the land claims outlined in 1825 to force numerous tribes in Indiana, southern Michigan and southern Wisconsin to move to Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, and Oklahoma. These included the Odawa and Potawatomi, two closely related and allied tribes to the Ojibwa.[28]

In 1848, Wisconsin achieved statehood as more and more Indian nations faced removal and marginalization. Corrupt Indian agents controlled annuity payments and took authority not granted them by the bands. White settlers moved onto Ojibwa lands and refused them the rights reserved at the treaty signings. The Ojibwa complained to the president about the mistreatment and broken promises, but politicians were more apt to listen to western land speculators who saw possibilities for profit in removing the Ojibwa to Minnesota.[28]

Even with the promises of 1837 and 1842, worries of Ojibwa removal remained on the horizon. Buffalo kept in constant contact with the other bands to make sure the Ojibwa kept their part of the bargain. He sent runners to all the bands to report back on any conduct by the Ojibwa that could construed as grounds for removal. Nothing was reported. Regardless, President Zachary Taylor signed the removal order on February 6, 1850, under corrupt circumstances, claiming to be protecting the Ojibwa from "injurious" whites.[28] The order was resisted by the Wisconsin legislature, and plans for removal were set aside. However, Alexander Ramsey, the territorial governor of Minnesota, and Indian sub-agent John Watrous conspired on a plan to force the Ojibwa to Minnesota anyway, the two men standing to gain economic and political benefits from such a move.[29]

Sandy Lake Tragedy

To force the Ojibwa to comply, the subagent Watrous announced he would only pay future annuities at Sandy Lake, Minnesota instead of La Pointe where they had been paid previously. The result was the Sandy Lake Tragedy where hundreds of Ojibwas starved or died of exposure in Minnesota and on the journey home when the promised supplies were late and inadequate. In a later letter, Buffalo described the conditions as such:

And when a message was sent to me by our Indian agent to come and get our pay, I lost no time in arising & complying with my Agents voice and when I reached my point of destination, verily my Agent fed me with very bad flour it resembled green clay. Soon I became sick and many of my fellow chippewas also were taken sick, and soon the results were manifested by the death of over two hundred persons of my tribe, for this calamity, I laid blame to the provisions issued to us...[30]

Back in La Pointe, Buffalo undertook a series of actions to stop any further efforts at removal. He and other leaders would continue to petition the government for the next two years to no avail. However, they were able to win considerable sympathy from whites who heard of the debacle in Sandy Lake, and newspapers throughout the Lake Superior region ran editorials condemning the removal effort. Buffalo sent two of his sons to St. Paul and they were able to obtain a portion of the annuities still owed. Still, Ramsey and Watrous had not abandoned their hopes of moving the Ojibwa to Sandy Lake. After even Watrous was able to admit they saw Sandy Lake as a "graveyard," he still attempted to move all the bands to Fond du Lac.[31] Young Ojibwa men in Wisconsin were outraged at these developments and the threat of violent revolt grew. Buffalo called on his well-spoken sub-chief Oshoga, and Benjamin Armstrong a literate white interpreter married to Buffalo's daughter, and drew up a petition that the 92 year old Buffalo would personally deliver to the president in Washington.[32]

Trip to Washington

After spring thaw in 1852, the elderly Buffalo, Oshaga, Armstrong, and four others set out from La Pointe for Washington D.C. by birch bark canoe. Along the way, they stopped in towns and mining camps along the Michigan shore of Lake Superior and secured hundreds of signatures in support of their cause. At Sault Ste. Marie, they were held by the Indian agent, who informed them that no unauthorized Ojibwa delegations could go to Washington and they had to turn back. The men pleaded the urgency of their case and were let through to Detroit by steamship where another Indian agent tried to stop them. Once allowed to proceed, they sailed to Buffalo, New York and then on to Albany and New York City.[33]

In New York City, they became something of a curiosity and were able to generate publicity and money for their cause. In Washington, however, they were turned away by Indian Affairs, and told they never should have come in the first place. Luckily, they drew the attention of the Whig Congressman Briggs from New York who was able to schedule a meeting with President Millard Fillmore the next day. At the meeting, Buffalo rose first and performed the pipe ceremony with a pipe made especially for the occasion. He then had the younger chief Oshaga speak for more than an hour about the broken treaty promises and the disastrous attempt at removal. Fillmore agreed to consider the issues and announced the next day that the removal order would be canceled, annuity payments would be at La Pointe, and another treaty would set up permanent reservations.[33]

The delegation traveled back to Wisconsin by rail, spreading the good news to the various Ojibwa bands as they went. Buffalo also announced that all should gather at the La Pointe payments the next summer (1853) and he would reveal the specifics of the agreement.[34]

1854 Treaty and Buffalo Estate

- For full article see Treaty of La Pointe (1854)

As promised by Fillmore, treaty commissioners arrived in La Pointe in 1854 to come to agreement on a final treaty. With the negative experiences of 1837 and 1842 fresh in their memory, the Ojibwa leaders sought to control the negotiations in 1854. Ambiguity in those treaties had been partially to blame, so Buffalo insisted he would accept no interpreter other than Armstrong, who he now referred to as his adopted son. The Ojibwa insisted on a guarantee of the right to hunt, fish, and gather on all the ceded territory, and on the establishment on several reservations across western Upper Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and northeastern Minnesota. Buffalo, in his mid-nineties and in failing health, directed the negotiations but left most of the speaking to other chiefs and entrusted Armstrong with seeing that all the details were taken care of in the written version.

These reservations in Wisconsin became the Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation, Lac du Flambeau Indian Reservation, and for the La Pointe Band, a reservation at Bad River around the Band's traditional wild ricing grounds, and some reserved land for fishing grounds at the eastern tip of Madeline Island. In Minnesota, the reservations for the Fond du Lac and the Grand Portage Bands were established, with pending negotiations promised for the Bois Forte Band. In Michigan, reservations for the Lac Vieux Desert, Ontonagon and L'Anse Bands were established. The St. Croix and Sokaogon bands left the negotiations in protest and were excluded from the agreement.[35]

A small tract of land was also set aside for Chief Buffalo and his family at Buffalo Bay on the mainland across from Madeline Island at a place called Miskwaabikong (red rocks or cliffs). Many of the Catholic and mixed-blooded members of the La Pointe Band elected to settle there instead of at Bad River. In 1855, this settlement at the "Buffalo Estate" was acknowledged and was extended by executive order into what is now called the Red Cliff Indian Reservation.[36]

Death and legacy

Chief Buffalo was too ill to participate in the speeches surrounding the annuity payments in summer 1855, an event marked by accusations of official corruption, threats of violence by members of the American Fur Company, and infighting among the Ojibwa bands. Morse records that these conflicts worsened Buffalo's condition, and he died of heart disease on September 7, 1855, at La Pointe.[25] Members of his band blamed the conduct of the government officials for his death.

He was described as "head and the chief of the Chippewa Nation" and a man respected "for his rare integrity, wisdom in council, power as an orator, and magnanimity as a warrior." His funeral was conducted in military fashion, with volleys fired at intervals in his honor. In his final hours he requested that his tobacco pouch and pipe be carried to Washington, D.C.[37]

Today, Great Chief Buffalo is regarded a hero of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Those at Red Cliff also remember him as a founding figure. His life is celebrated during commemorations of the treaty signings and the Sandy Lake Tragedy. During the series of treaty conflicts some call the Wisconsin Walleye War, his name was frequently invoked as one who refused to give up his homeland and tribal sovereignty. His descendants, many going by the surname "Buffalo" are widespread in Red Cliff and Bad River. Missionary Edmund Ely identified later Ojibwe chief John Little Wolf or Maiingans was his son.[38] He is buried in the Catholic Indian cemetery at La Pointe, near the deep, cold waters of Ojibwe Gichigami (Lake Superior), the "great freshwater-sea of the Ojibwa".

See also

Notes

- ↑ Although the original term Ojibwe as "Ojibwa" is now preferred to its English corruption "Chippewa," Chippewa has historically been the dominant English usage, was used in treaties with the United States, and remains part of the official name of many tribal groups: Lake Superior Chippewa, Red Cliff Chippewa, etc.

- ↑ Loew, 20-21.

- ↑ Loew, 56-58.

- ↑ Loew, 8.

- ↑ Warren, 11. There is some confusion over which doodem Buffalo belonged to. Using oral accounts of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, in some of its material, the Wisconsin Historical Society claims Buffalo and other chiefs in Wisconsin sent a letter or "Symbolic Petition of Chippewa Chiefs" to Washington, DC, shortly before the Sandy Lake Tragedy on January 28, 1849; in which Buffalo is represented by a crane rather than a loon, or that the letter was sent shortly after the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Schoolcraft, who collected and published the petition in 1851 claimed it was sent in 1849 by Ojibwa leaders around the headwaters of the Wisconsin River and not by Buffalo or chiefs from La Pointe.

- ↑ Morse, 367

- ↑ Schoolcraft (American Indians), 261.

- ↑ Warren, 87-89

- ↑ Schoolcraft (1851), 195. Buffalo's obituary, drawing off the memoirs of his adopted white son Benjamin Armstrong call Andaigweos the father. However, Warren and Schoolcraft both describe Ou-daig-weos as the grandfather of Buffalo. Some accounts instead claim that Buffalo was the son of chief Waubojeeg, and brother to Susan Johnston (also known as Ozhaguscodaywayquay) who was the wife of the fur-trader John Johnston and mother of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, wife of Henry Schoolcraft. Schoolcraft describes Ou-daig-weos and Waubojeeg as being of the "same lineage." However, he does not claim Buffalo is the son of Waubojeeg. Modern sources may be confused by the fact that Waubojeeg had a son named Weshki (New), which is similar to Gichi-weshkiinh (Great renewer).

- ↑ Morse, 368.

- ↑ See ref.3. According to the U.S. Senate website and Holzhueter (1973, 1986), Chief Buffalo returned to Washington, D.C. in February 1855 as part of a delegation of 16 Ojibwa Indians from Wisconsin and Minnesota. However, it is likely that this trip was taken instead by the Leech Lake Chief also known as Beshekee. These sources also state that Chief Buffalo had his likeness modeled in clay and was carved from life in a marble bust from which a bronze copy was later made. These pieces are today part of the Capitol art collection. If Great Chief Buffalo indeed made this trip to Washington in 1855, he would have been 95 or 96 years of age. The sculptures portray a powerfully built and still vigorous man, one looking much younger than this advanced chronological age, proving, it would seem, that Buffalo lived up to his name until the end of his days.

- ↑ Morse, 365-69.

- ↑ Warren, 324.

- ↑ Armstrong, 196-98.

- ↑ Morse, 367.

- ↑ Schoolcraft (Personal Memories), 103.

- ↑ Loew, 58-59

- ↑ Warren 47

- ↑ Schoolcraft (1834), 21.

- ↑ Schoolcraft (1834), 271.

- ↑ qtd. in Satz, 131-157.

- ↑ Satz, 24.

- ↑ qtd. in Satz, 31.

- ↑ Satz, 38-40.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Morse, 366.

- ↑ Satz, 40.

- ↑ Loew, 60-61.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Loew, 61.

- ↑ Satz, 55-59.

- ↑ qtd. in Satz, Gulig, & St. Germaine, 154

- ↑ Satz, 54-61

- ↑ Armstrong, 16.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Armstrong, 16-32.

- ↑ Loew, 62.

- ↑ Loew, 63.

- ↑ "Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa". Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa: Tribal Government, Origins and History. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ Morse, 365-369.

- ↑ Ely, 110

References

- Armstrong, Benjamin. (1891) Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the life of Benjamin G. Armstrong. T.P. Wentworth Ashland, WI: Wentworth.

- Diedrich, Mark. (1999) Ojibway Chiefs: Portraits of Anishinaabe Leadership. ISBN 0-9616901-8-6

- Ely, Edmund F. (2012). The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. University of Nebraska Press

- Holzhueter, John O. 1973. Chief Buffalo and Other Wisconsin-Related Art in the National Capitol, Wisconsin Magazine of History 56: 4, p. 284-88.

- Holzhueter, John O. 1986. Madeline Island & the Chequamegon Region. Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin. pp. 49–50.

- Loew, Patty. (2001). Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

- Morse, Richard E. (1855). "The Chippewas of Lake Superior" in Wisconsin Historical Society Collections, v. III, Madison, 1904. pp. 365–369.

- Satz, Ronald N. (1997). Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin's Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Satz, Ronald N., Anthony G. Gulig, and Richard St. Germaine. (1991). Classroom Activities on Chippewa Treaty Rights. Madison: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. (1834). Narrative of an Expedition Through the Upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake. New York: Harper.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. (1851). The American Indians: Their History, Condition and Prospects, from Original Notes and Manuscripts. Buffalo: Derby.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. (1851). Personal Memories of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, and Co.

- Warren, William W. (1851). History of the Ojibways Based Upon Traditions and Oral Statements. Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society.

- "Death of Buffalo Chief," Superior Chronicle [Superior, Wis.], October 23, 1855.

External links

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- U.S. Senate Website: Art & History, Sculpture, Be sheekee, or Buffalo.

- Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Chief Buffalo's Petition to the President

- Chief Buffalo's biography at the United States Government Printing Office

- Image of Grave of Bez Hike - Chief of the Chippewas at Minnesota Historical Society

- The Chief Buffalo Mural Project

- Chief Buffalo's Diplomacy and The Debate Over Ojibwe Removal

- Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong