Kashtiliash IV

| Kaštiliašu IV | |

|---|---|

| King of Babylon | |

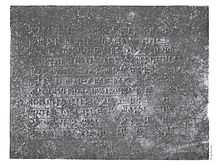

The Tablet of Akaptaḫa, recording a gift of land by Babylonian king, Kaštiliašu IV | |

| Reign | ca. 1232–1225 BC |

| Predecessor | Šagarakti-Šuriaš |

| Successor | Enlil-nādin-šumi |

| Royal House | Kassite |

Kaštiliašu IV was the twenty-eighth Kassite king of Babylon and the kingdom contemporarily known as Kar-Duniaš, ca. 1232–1225 BC (short chronology). He succeeded Šagarakti-Šuriaš, who could have been his father, ruled for eight years,[i 1] and went on to wage war against Assyria resulting in the catastrophic invasion of his homeland and his abject defeat.

He may have ruled from the Palace of the Stag and the Palace of the Mountain Sheep, in the city of Dur-Kurigalzu, as these are referenced in a jeweler’s archive from this period.[1] Despite his short reign there are at least 177 economic texts dated to him,[2] on subjects as diverse as various items for a chariot, issue of flour, dates, oil and salt for offerings, receipt of butter and oil at the expense of the šandabakku (the governor of Nippur), i.e. his shopping receipt, and baskets received by Rimutum from Hunnubi.[3][i 2]

War with Assyria

According to his eponymous epic, Tukulti-Ninurta I, king of Assyria, was provoked into war by Kaštiliašu’s dastardly preemptive attack on his territory, thereby breaching an earlier treaty between their ancestors Adad-nīrāri I and Kadašman-Turgu.[4] But trouble may have been brewing for some time. Tudḫaliya, king of the Hittites, himself reeling from defeat by the Assyrians at the Battle of Nihriya, refers to the Babylonian king as his equal, in his treaty with his vassal, Šaušgamuwa of Amurru, hinting at the possible existence of an alliance or at least a tacit understanding between them.[5] It reads:

The kings who are equal to me (are) the king of Egypt, the king of Karanduniya (Babylon), the king of Assyria <and the king of Aḫḫiyawa>.

And if the king of Karanduniya is My Majesty's friend, he shall also be your friend; but if he is My Majesty's enemy, he shall also be your enemy.

Since the king of Assyria is My Majesty's enemy he shall also be your enemy.

Your merchant shall not enter into Assyria and you shall not allow his merchant into your land. He shall not pass through your land.

But if he enters into your land, you should seize him and send him off to My Majesty.[6]—Treaty between Tudḫaliya and Šaušgamuwa, Tablet A, column IV, lines 1-18 edited

Also, Kaštiliašu had granted land and presumably asylum to a Hurrian, a fugitive from Assyria’s vassal Ḫanigalbat, commemorated on the Tablet of Akaptaḫa.[2] He also reconfirmed a large gift of land on a kudurru that had been provided to Uzub-Šiḫu or -Šipak by the Kassite king, Kurigalzu II (ca. 1332-1308 BC) in grateful recognition of his service in an earlier war against Assyria.[i 3]

Tukulti-Ninurta petitioned the god Šamaš before beginning his counter offensive.[7] Kaštiliašu was captured, single-handed by Tukulti-Ninurta according to his account, who “trod with my feet upon his lordly neck as though it were a footstool”[8] and deported him ignominiously in chains to Assyria. The victorious Assyrian demolished the walls of Babylon, massacred many of the inhabitants, pillaged and plundered his way across the city to the Esagila temple, where he made off with the statue of Marduk.[9] He then proclaimed himself “king of Karduniash, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of Sippar and Babylon, king of Tilmun and Meluhha.”[7] Middle Assyrian texts recovered at modern Tell Sheikh Hamad, ancient Dūr-Katlimmu, which was the regional capital of the vassal Ḫanigalbat, include a letter from Tukulti-Ninurta to his sukkal rabi’u, or grand vizier, Aššur-iddin advising him of the approach of Šulman-mušabši escorting a Babylonian king, who may have been Kaštiliašu, his wife, and his retinue which incorporated a large number of women,[10] on his way to exile after his defeat. The journey to Dūr-Katlimmu seems to have traveled via Jezireh.[11]

The conflict, and its outcome, is recorded in the Tukulti-Ninurta Epic, a poetic “victory song”, which has been recovered in several lengthy fragments, somewhat reminiscent of the earlier account of Adad-nīrāri’s victory over Nazi-Maruttaš.[7] It would lend its form to later Assyrian epics such as that of Shalmaneser III, concerning his campaign in Ararat.[12] Written strictly from the Assyrian point of view, it provides a strongly biased narrative. Tukulti-Ninurta is portrayed as an innocent victim of the invidious Kaštiliašu, who is contrasted as “the transgressor of an oath”, and who has so vexed the gods that they have abandoned their sanctuaries.[13]

More succinct accounts of these events are also inscribed on five large limestone tablets which were imbedded in Tukulti-Ninurta’s construction projects as foundation stones, for example the Annals of Tukulti-Ninurta, carved on a slab which was buried in or under the wall of his purpose-built capital, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.[14]

Relations with Elam

There is no extant evidence of conflict between Elam and Babylon during his reign. The ruling families had been joined through intermarriage in the past, but the countries had resorted to war to settle their differences under the reigns of Kurigalzu I and possibly Nazi-Maruttaš. However, the sequence of kings of Elam during this period is very confused, with several names suspiciously appearing over again some in shuffled sequences, such as Napirisha-Untash and Untash-Napirisha, making it hard to make sense of the chronology. After Kaštiliašu’s overthrow, however, Kidin-Hutran III, the king of Elam, certainly led two successive incursions into Babylonia, which have been explained as either indicative of his loyalty to the fallen Kassite dynasty or alternatively raiding with impunity to exploit the weakness of the over-extended Assyrians.[15]

Babylon under Assyrian Governorship

The Chronicle P records that Tukulti-Ninurta ruled through his appointed governors for seven years, where the term šaknūtīšu could include appointees or prefects.[i 4] Alternative reconstructions of these events have been proposed whereby Tukulti Ninurta ruled for seven years and then three successive Kassite kings took power before the original dynasty was reinstated[16] or that his own rule followed these kings.[17]

It has been suggested that the Šulgi Prophecy, a vaticinium ex eventu (prophesy after the fact) composition of uncertain date, might refer to the events during one of these reigns.[18] Enlil-nādin-šumi may be the subject of Column V of the Šulgi prophetic speech.[19] It is preserved in heavily damaged late-period tablets, in which Šulgi (2112-2004 BC), the second and most famous king of the third dynasty of Ur, and founder of Nippur, summarizes his achievements. He predicts that Babylon will submit to Assyria, Nippur will be “cast down”, Enlil will remove the king, another king will make a messianic appearance, restore the shrines and Nippur will rise from its ashes.[20]

With the collapse of Tukulti-Ninurta’s regime in Babylonia, some years before his assassination, the Kassite rabûti (important men, noblemen, officers?)[2] rebelled and installed Kaštiliašu’s son, Adad-šuma-ušur, on the throne.[i 4]

Inscriptions

- ↑ Kinglist A, BM 33332, column 2, lines 7-10.

- ↑ Tablets BM 17678, 17712, 17687, 17740.

- ↑ Kudurru of Kaštiliašu, Sb 30 in the Musée du Louvre.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chronicle P (ABC 22), BM 92701, column 4, lines 7 and 8, 14-16, 17-20.

References

- ↑ Andrew George (2004). "Palace names and epithets, and the vaulted building". Sumer (School of Oriental and African Studies) 51: 39.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 J. A. Brinkman (1976). "Kaštiliašu". Materials and Studies for Kassite History, Vol. I (MSKH I). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 175–189.

- ↑ M. Sigrist, H. H. Figulla and C. B. F. Walker (1996). Catalogue of Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum, Volume II. British Museum Press. pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2003). Letters of the great kings of the ancient Near East: the royal. Routledge. p. 11.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2005). The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford University Press. pp. 494, 318.

- ↑ Itamar Singer (2003). "Treaties". In William W. Hallo. The Context of Scripture: Volume II: Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World. Brill. p. 99.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 J. M. Munn-Rankin (1975). "Assyrian Military Power, 1300-1200 B.C.". In I. E. S. Edwards. Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region, c. 1380-1000 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 287–288, 298.

- ↑ Albert Kirk Grayson (1972). Assyrian Royal Inscriptions: Volume I. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 108. §716.

- ↑ Christopher Morgan (2006). Mark William Chavalas, ed. The ancient Near East: historical sources in translation. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 145–152.

- ↑ Frederick Mario Fales (2010). "Production and Consumption at Dūr-Katlimmu: A Survey of the Evidence". In Hartmut Kühne. Dūr-Katlimmu 2008 and beyond. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 82.

- ↑ Hartmut Kühne (1999). "Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad - The Assyrian City of Dūr-Katlimmu: A Historic-Geographic Approach". In Prince Mikasa no Miya Takahito. Essays on ancient Anatolia in the second millennium B.C. Harrassowitz. p. 282.

- ↑ Benjamin R. Foster. Carl S. Ehrlich, ed. From an antique land: an introduction to ancient Near Eastern literature. p. 200.

- ↑ John F. Kutsko (2000). Between Heaven and Earth: divine presence and absence in the Book of Ezekiel. Eisenbrauns. p. 106.

- ↑ L. W. King (1904). Records of the reign of Tukulti-Ninib I, King of Assyria, about B.C. 1275. Luzac and Co. pp. 78–95.

- ↑ D. T. Potts (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–231.

- ↑ C.B.F. Walker (May 1982). "Babylonian Chronicle 25: A Chronicle of the Kassite and Isin II Dynasties". In C. Van Driel. Assyriological Studies presented to F. R. Kraus on the occasion of his 70th birthday. London: Netherlands Institute for the Near East. pp. 402–406.

- ↑ Shigeo Yamada (2003). "Tukulti-Ninurta I's Rule over Babylonia and its Aftermath - A Historical Reconstruction". Orient 38: 153–177.

- ↑ J. A. Brinkman. "Enlil-nādin-šumi". MSKH I. p. 125.

- ↑ Albert Kirk Grayson (1975). Assyrian and Babylonian chronicles. J. J. Augustin. p. 290.

- ↑ Bernard McGinn, John J. Collins, Stephen J. Stein (2003). The Continuum history of apocalypticism. Continuum. pp. 10–11.