Kähler manifold

In mathematics and especially differential geometry, a Kähler manifold is a manifold with three mutually compatible structures; a complex structure, a Riemannian structure, and a symplectic structure.

Kähler manifolds find important applications in the field of algebraic geometry where they represent generalizations of complex projective algebraic varieties via the Kodaira embedding theorem (Hartshorne 1977). They are named after German mathematician Erich Kähler.

Definitions

Since Kähler manifolds are naturally equipped with several compatible structures, there are many equivalent ways of creating Kähler forms.

Symplectic viewpoint

A Kähler manifold is a symplectic manifold  equipped with an integrable almost-complex structure which is compatible with the symplectic form.[1]

equipped with an integrable almost-complex structure which is compatible with the symplectic form.[1]

Complex viewpoint

A Kähler manifold is a Hermitian manifold whose associated Hermitian form is closed. The closed Hermitian form is called the Kähler metric.

Equivalence of definitions

Every Hermitian manifold  is a complex manifold which comes naturally equipped with a Hermitian form

is a complex manifold which comes naturally equipped with a Hermitian form  and an integrable, almost complex structure

and an integrable, almost complex structure  . Assuming that

. Assuming that  is closed, there is a canonical symplectic form defined as

is closed, there is a canonical symplectic form defined as  which is compatible with

which is compatible with  , hence satisfying the first definition.

, hence satisfying the first definition.

On the other hand, any symplectic form compatible with an almost complex structure must be a complex differential form of type  , written in a coordinate chart

, written in a coordinate chart  as

as

for  . The added assertions that

. The added assertions that  be real-valued, closed, and non-degenerate guarantee that the

be real-valued, closed, and non-degenerate guarantee that the  define Hermitian forms at each point in

define Hermitian forms at each point in  .[1]

.[1]

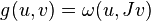

Connection between Hermitian and symplectic definitions

Let  be the Hermitian form,

be the Hermitian form,  the symplectic form, and

the symplectic form, and  the almost complex structure. Since

the almost complex structure. Since  and

and  are compatible, the new form

are compatible, the new form  is Riemannian.[1] One may then summarize the connection between these structures via the identity

is Riemannian.[1] One may then summarize the connection between these structures via the identity  .

.

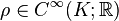

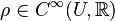

Kähler potentials

If  is a complex manifold, it can be shown[1] that every strictly plurisubharmonic function

is a complex manifold, it can be shown[1] that every strictly plurisubharmonic function  gives rise to a Kähler form as

gives rise to a Kähler form as

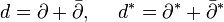

where  are the Dolbeault operators. The function

are the Dolbeault operators. The function  is said to be a Kähler potential.

is said to be a Kähler potential.

In fact, utilizing the holomorphic version of the Poincaré lemma, a partial converse holds true locally. More specifically, if  is a Kähler manifold then about every point

is a Kähler manifold then about every point  there is a neighbourhood

there is a neighbourhood  containing

containing  and a function

and a function  such that

such that  and here

and here  is termed a (local) Kähler potential.

is termed a (local) Kähler potential.

Ricci tensor and Kähler manifolds

- see Kähler manifolds in Ricci tensor.

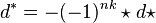

The Laplacians on Kähler manifolds

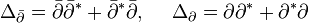

Let  be the Hodge operator and then on an differential manifold X we can define the Laplacian as

be the Hodge operator and then on an differential manifold X we can define the Laplacian as

where

where  is the exterior derivative and

is the exterior derivative and  . Furthermore if X is Kähler then

. Furthermore if X is Kähler then  and

and  are decomposed as

are decomposed as

and we can define another Laplacians

that satisfy

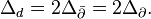

From these facts we obtain the Hodge decomposition (see Hodge theory)

where  is r-degree harmonic form and

is r-degree harmonic form and  is {p,q}-degree harmonic form on X. Namely, an differential form

is {p,q}-degree harmonic form on X. Namely, an differential form  is harmonic if and only if each

is harmonic if and only if each  belong to the {i,j}-degree harmonic form.

belong to the {i,j}-degree harmonic form.

Further, if X is compact then we obtain

where  is

is  -harmonic cohomology group. This means that if

-harmonic cohomology group. This means that if  is an differential form with {p,q}-degree there is only one element in {p,q}-harmonic form due to Dolbeault theorem.

is an differential form with {p,q}-degree there is only one element in {p,q}-harmonic form due to Dolbeault theorem.

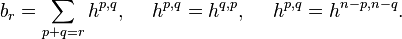

Let  , called Hodge number, then we obtain

, called Hodge number, then we obtain

The LHS of the first identity, br, is r-th Betti number, the second identity comes from that since the Laplacian  is a real operator

is a real operator  and the third identity comes from Serre duality.

and the third identity comes from Serre duality.

Applications

On a Kähler manifold, the associated Kähler form and metric are called Kähler–Einstein (or sometimes Einstein–Kähler) if its Ricci tensor is proportional to the metric tensor,  , for some constant λ. This name is a reminder of Einstein's considerations about the cosmological constant. See the article on Einstein manifolds for more details.

, for some constant λ. This name is a reminder of Einstein's considerations about the cosmological constant. See the article on Einstein manifolds for more details.

Originally the Kähler condition is independent on the Einstein condition, in which Ricci tensor is proportional to Riemannian metric with constant real number. The important point is that if X is Kähler then Christoffel symbols  vanish and Ricci curvature is much simplified. The Kähler condition, therefore, is closely related with Ricci curvature. In fact Aubin and Yau prove the Calabi conjecture using the fact that on a compact Kähler manifold with the first Chern class c1=0 there is a unique Ricci-flat Kähler metric in each Kähler class. But in non-compact case the situation turns to be more complicated and the final solution might not be reached.

vanish and Ricci curvature is much simplified. The Kähler condition, therefore, is closely related with Ricci curvature. In fact Aubin and Yau prove the Calabi conjecture using the fact that on a compact Kähler manifold with the first Chern class c1=0 there is a unique Ricci-flat Kähler metric in each Kähler class. But in non-compact case the situation turns to be more complicated and the final solution might not be reached.

Examples

- Complex Euclidean space Cn with the standard Hermitian metric is a Kähler manifold.

- A torus Cn/Λ (Λ a full lattice) inherits a flat metric from the Euclidean metric on Cn, and is therefore a compact Kähler manifold.

- Every Riemannian metric on a Riemann surface is Kähler, since the condition for ω to be closed is trivial in 2 (real) dimensions.

- Complex projective space CPn admits a homogeneous Kähler metric, the Fubini–Study metric. An Hermitian form in (the vector space) Cn + 1 defines a unitary subgroup U(n + 1) in GL(n + 1,C); a Fubini–Study metric is determined up to homothety (overall scaling) by invariance under such a U(n + 1) action. By elementary linear algebra, any two Fubini–Study metrics are isometric under a projective automorphism of CPn, so it is common to speak of "the" Fubini–Study metric.

- The induced metric on a complex submanifold of a Kähler manifold is Kähler. In particular, any Stein manifold (embedded in Cn) or projective algebraic variety (embedded in CPn) is of Kähler type. This is fundamental to their analytic theory.

- The unit complex ball Bn admits a Kähler metric called the Bergman metric which has constant holomorphic sectional curvature.

- Every K3 surface is Kähler (by a theorem of Y.-T. Siu).

An important subclass of Kähler manifolds are Calabi–Yau manifolds.

Properties

(Deligne et al. 1975) showed that all Massey products vanish on a Kähler manifold. Manifolds with such vanishing are formal: their real homotopy type follows ("formally") from their real cohomology ring.

See also

- Hermitian manifold

- Almost complex manifold

- Hyper-Kähler manifold

- Kähler–Einstein metric

- Quaternion-Kähler manifold

- Complex Poisson manifold

- Einstein manifold

- Calabi conjecture

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Canas da Silva, Ana (2008). Lectures on Symplectic Geometry. Springer. ISBN 978-3540421955.

- Deligne, P.; Griffiths, Ph.; Morgan, J.; Sullivan, D., (1975), "Real homotopy theory of Kähler manifolds", Invent. Math. 29: 245–274, doi:10.1007/BF01389853

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, OCLC 13348052, MR 0463157

- Alan Huckleberry and Tilman Wurzbacher, eds. Infinite Dimensional Kähler Manifolds (2001), Birkhauser Verlag, Basel ISBN 3-7643-6602-8.

- Andrei Moroianu, Lectures on Kähler Geometry (2007), London Mathematical Society Student Texts 69, Cambridge ISBN 978-0-521-68897-0.

- Andrei Moroianu, Lectures on Kähler Geometry (2004), http://www.math.polytechnique.fr/~moroianu/tex/kg.pdf

- André Weil, Introduction à l'étude des variétés kählériennes (1958)

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Kähler manifold", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4