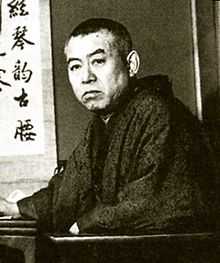

Jun'ichirō Tanizaki

| Tanizaki Jun'ichirō | |

|---|---|

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō | |

| Born |

24 July 1886 Nihonbashi, Tokyo, Japan |

| Died |

30 July 1965 (aged 79) Yugawara, Kanagawa, Japan |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Genres | fiction, drama, essays, silent film scenarios |

Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (谷崎 潤一郎 Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, 24 July 1886 – 30 July 1965) was a Japanese author, one of the major writers of modern Japanese literature, and perhaps the most popular Japanese novelist after Natsume Sōseki. Some of his works present a rather shocking world of sexuality and destructive erotic obsessions; others, less sensational, subtly portray the dynamics of family life in the context of the rapid changes in 20th-century Japanese society. Frequently his stories are narrated in the context of a search for cultural identity in which constructions of "the West" and "Japanese tradition" are juxtaposed.

Biography

Early life

Tanizaki was born to a well-off merchant class family in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, where his uncle owned a printing press, which had been established by his grandfather. In his Yōshō Jidai (Childhood Years, 1956) Tanizaki admitted to having had a pampered childhood. His childhood house was destroyed in the 1894 Meiji Tokyo earthquake, which Tanizaki later attributed to his lifelong phobia for earthquakes. His family's finances declined dramatically as he grew older until he was forced to reside in another household as a tutor. Despite these financial problems, he attended the Tokyo First Middle School, where he became acquainted with Isamu Yoshii. Tanizaki attended the Literature Department of Tokyo Imperial University from 1908 but was forced to drop out in 1911 because of his inability to pay for tuition.

Early literary career

Tanizaki began his literary career in 1909. His first work, a one-act stage play, was published in a literary magazine which he helped found. Tanizaki's name first became widely known with the publication of the short story Shisei (The Tattooer) in 1910. In the story, a tattoo artist inscribes a giant spider on the body of a beautiful young woman. Afterwards, the woman's beauty takes on a demonic, compelling power, in which eroticism is combined with sado-masochism. The femme-fatale is a theme repeated in many of Tanizaki's early works, including Kirin (1910), Shonen ("The Children", 1911), Himitsu ("The Secret," 1911), and Akuma ("Devil", 1912).

Tanizaki's other works published in the Taishō period include Shindo (1916) and Oni no men (1916), which are partly autobiographical. Tanizaki married in 1915, and his first child, a daughter, was born in 1916; however, it was an unhappy marriage and in time he encouraged a relationship between his first wife, Chiyoko, and his friend and fellow writer Haruo Satō. The psychological stress of this situation is reflected in some of his early works, including the stage play Aisureba koso (Because I Love Her, 1921) and his novel Kami to hito no aida (Between Men and the Gods, 1924). Nevertheless, even though some of Tanizaki's writings seem to have been inspired by persons and events in his life, his works are far less autobiographical than those of most of his contemporaries in Japan.

In 1918, he toured Korea, northern China and Manchuria. In his early years Tanizaki became infatuated with the West and all things modern. In 1922 he relocated from Odawara (where he had been living since 1919) to Yokohama, which had a large expatriate population, living briefly in a Western-style house and leading a decidedly bohemian lifestyle. This outlook is reflected in some of his early writings.

Tanizaki had a brief career in Japanese silent cinema working as a script writer for the Taikatsu film studio. He was a supporter of the Pure Film Movement and was instrumental in bringing modernist themes to Japanese film.[1] He wrote the scripts for the films Amateur Club (1922) and A Serpent's Lust (1923) (based on the story of the same title by Ueda Akinari, which was, in part, the inspiration for Mizoguchi Kenji's 1953 masterpiece Ugetsu monogatari). Some have argued that Tanizaki's relation to cinema is important to understanding his overall career.[2]

Period in Kyoto

Tanizaki's reputation began to take off when he moved to Kyoto after the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake, which destroyed his house in Yokohama (Tanizaki was at the time on a bus in Hakone and thus escaped injury). The loss of Tokyo's historic buildings and neighborhoods in the quake triggered a change in his enthusiasms, as he redirected his youthful love for the imagined West and modernity into a renewed interest in Japanese aesthetics and culture, particularly the culture of the Kansai region comprising Osaka, Kobe and Kyoto. His first novel after the earthquake, and his first truly successful novel, was Chijin no ai (Naomi, 1924-25), which is a tragicomic exploration of class, sexual obsession, and cultural identity. Tanizaki made another trip to China in 1926, where he met Guo Moruo, with whom he later maintained correspondence. He relocated from Kyoto to Kobe in 1928.

Inspired by the Osaka dialect, Tanizaki wrote Manji (Quicksand, 1928–1929), in which he explored lesbianism, among other themes. This was followed by the classic Tade kuu mushi (Some Prefer Nettles, 1928–29), which depicts the gradual self-discovery of a Tokyo man living near Osaka, in relation to Western-influenced modernization and Japanese tradition. Yoshinokuzu (Arrowroot, 1931) alludes to Bunraku and kabuki theater and other traditional forms even as it adapts a European narrative-within-a-narrative technique. His experimentation with narrative styles continued with Ashikari (The Reed Cutter, 1932), Shunkinsho (A Portrait of Shunkin, 1933), and many other works that combine traditional aesthetics with Tanizaki's particular obsessions.

His renewed interest in classical Japanese literature culminated in his multiple translations into modern Japanese of the eleventh-century classic The Tale of Genji and in his masterpiece Sasameyuki (A Light Snowfall, published in English as The Makioka Sisters, 1943–1948), a detailed characterization of four daughters of a wealthy Osaka merchant family who see their way of life slipping away in the early years of World War II. The Makiokas live a remarkably cosmopolitan life, with European neighbours and friends without suffering the cultural-identity crises common to earlier Tanizaki characters. When he began to serialize it, the editors of Chūōkōron were warned it did not contribute to the needed war spirit and, fearful of losing supplies of paper, cut off the serialization.[3] Tanizaki relocated to the resort town of Atami, Shizuoka in 1942, but returned to Kyoto in 1946.

Postwar period

After World War II Tanizaki again emerged into literary prominence, winning a host of awards, and was until his death regarded as Japan's greatest contemporary author. He won the prestigious Asahi Prize in 1949, and was awarded the Order of Culture by the Japanese government in 1949 and in 1964 was elected to honorary membership in the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, the first Japanese writer to be so honoured.

His first major post-war work was Shōshō Shigemoto no haha (General Shigemoto's Mother, 1949–1950), with a moving restatement of the common Tanizaki theme of a son's longing for his mother. The novel also introduces the issue of sexuality in old age, which would reappear in Tanizaki’s later works, such as Kagi (The Key, 1956). Kagi is a lurid psychological novel, in which an aging professor arranges for his wife to commit adultery in order to boost his own sagging sexual desires. Tanizaki returned to Atami in 1950, and was designated a Person of Cultural Merit by the Japanese government in 1952. He suffered from paralysis of the right hand from 1958, and was hospitalized for Angina pectoris in 1960.

Tanizaki's characters are often driven by obsessive erotic desires. In one of his last novels, Futen Rojin Nikki (Diary of a Mad Old Man, 1961–1962), the aged diarist is struck down by a stroke brought on by an excess of sexual excitement. He records both his past desires and his current efforts to bribe his daughter-in-law to provide sexual titilation in return for Western baubles.

In 1964, Tanizaki was made a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Later that year, he moved to Yugawara, Kanagawa, south-west of Tokyo, where he died of a heart attack on 30 July 1965, shortly after celebrating his 79th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Hōnen-in in Kyoto.

Legacy

Many of Tanizaki's works are highly sensual, a few particularly centered on eroticism, and virtually all are laced with wit and ironic sophistication. Though he is remembered primarily for his novels and short stories, he also wrote poetry, drama, and essays.

Bibliography

Selected works

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Notes |

| 1910 | 刺青 Shisei |

The Tattooer | |

| 1913 | 恐怖 Kyōfu |

Terror | |

| 1918 | 金と銀 Kin to Gin |

Gold and Silver | |

| 1919 | 富美子の足 Fumiko no ashi |

Fumiko's Legs | |

| 1921 | 私 Watakushi |

The Thief | |

| 1922 | 青い花 Aoi hana |

Aguri | |

| 1924 | 痴人の愛 Chijin no Ai |

Naomi | a.k.a. A Fool's Love |

| 1926 | 友田と松永の話 Tomoda to Matsunaga no hanashi |

"Tomoda and Matsunaga's Story" | |

| 1926 | 青塚氏の話 "Aotsuka no Hanashi" |

"Mr. Bluemound" | |

| 1928– 1930 |

Manji |

Quicksand | Several film adaptations (1964, 1983, 1998 & 2006) |

| 1929 | 蓼喰う蟲 Tade kuu mushi |

Some Prefer Nettles | |

| 1931 | 吉野葛 Yoshino kuzu |

Arrowroot | |

| 1932 | 蘆刈 Ashikari |

The Reed Cutter | |

| 1933 | 春琴抄 Shunkinshō |

A Portrait of Shunkin | Film adaptation Opera adaptation |

| 陰翳礼讃 In'ei Raisan |

In Praise of Shadows | Essay on aesthetics | |

| 1935 | 武州公秘話 Bushukō Hiwa |

The Secret History of the Lord of Musashi | |

| 1936 | 猫と庄造と二人の女 Neko to Shōzō to Futari no Onna |

A Cat, A Man, and Two Women | Film adaptation |

| 1943– 1948 |

細雪 Sasameyuki |

The Makioka Sisters | Film adaptation |

| 1949 | 少将滋幹の母 Shōshō Shigemoto no haha |

Captain Shigemoto's Mother | |

| 1956 | 鍵 Kagi |

The Key | Film adaptation |

| 1957 | 幼少時代 Yōshō Jidai |

Childhood Years: A Memoir | |

| 1961 | 瘋癲老人日記 Fūten Rōjin Nikki |

Diary of a Mad Old Man | Film adaptation |

Some works published in English

- Naomi. Trans. Anthony Chambers. Vintage Press (2001). ISBN 0-375-72474-5

- The Key & Diary of a Mad Old Man. Trans. Howard Hibbert. Vintage Press (2004). ISBN 1-4000-7900-4

- Seven Japanese Tales Trans. Howard Hibbett. Vintage Press (1963). ISBN 0-679-76107-1

- The Gourmet Club Trans. Anthony Chambers and Paul McCarthy. Kodansha International (2001). ISBN 4-7700-2972-1

- The Makioka Sisters. Trans. Edward Seidensticker. Vintage Press (1995). ISBN 0-679-76164-0

- Some Prefer Nettles. Trans. Edward Seidensticker. Vintage Press (1995). ISBN 0-679-75269-2

- Quicksand. Trans. Howard Hibbett. Vintage Press (1995). ISBN 0-679-76022-9

- A Cat, a Man, and Two Women. Trans. Paul McCarthy. Kodansha International (1992). ISBN 4-7700-1605-0

- The Secret History of the Lord of Musashi and Arrowroot. Trans. Anthony Chambers. Vintage Press (2003). ISBN 0-375-71931-8

- Childhood Years: A Memoir. Trans. Paul McCarthy. Harper Collins in association with Kodansha International (1990). ISBN 0-00-654450-9

- The Reed Cutter and Captain Shigemoto's Mother. Trans. Anthony Chambers. Knopf, 1993.

- In Praise of Shadows. Trans. Edward Seidensticker and Thomas Harper. Leete's Island Books, 1977.

See also

- Torawakamaru the Koga Ninja

- Akuto, a film based on a Tanizaki story

References

Further reading

- Bernardi, Joanne (2001). Writing in Light: The Silent Scenario and the Japanese Pure Film Movement. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2926-8.

- Boscaro, Adriana, et al., eds. Tanizaki in Western Languages: A Bibliography of Translations and Studies. University of Michigan Press (1999). ISBN 0-939512-99-8

- Boscaro, Adriana and Anthony Chambers, eds. A Tanizaki Feast: The International Symposium in Venice. University of Michigan Press (1994). ISBN 0-939512-90-4

- Chambers, Anthony, The Secret Window: Ideal Worlds in Tanizaki's Fiction. Harvard University Asia Centre (1994). ISBN 0-674-79674-8

- Gessel, Van C. Three Modern Novelists. Kodansha International (1994). ISBN 4-7700-1652-2

- Ito, Ken Kenneth. Visions of Desire: Tanizaki's Fictional Worlds. Stanford University Press (1991). ISBN 0-8047-1869-5

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 10-ISBN 0674003349/13-ISBN 9780674003347; OCLC 44090600

- Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West. Columbia University Press (1998). ISBN 0-231-11435-4.

- Lamarre, Thomas (2005). Shadows on the Screen: Tanizaki Junʾichirō on Cinema and "Oriental" Aesthetics. Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 1-929280-32-7.

- Long, Margherita. This Perversion Called Love: Reading Tanizaki, Feminist Theory, and Freud. Stanford University Press (2009). isbn = 0804762333

External links

|