Juan Diego

| Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin | |

|---|---|

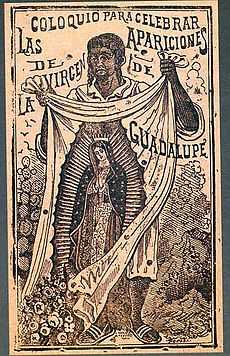

Juan Diego by Miguel Cabrera, 1752 | |

| Born |

1474 Cuauhtitlán, Mexico |

| Died |

1548 (aged 73–74) Tepeyac, Mexico |

| Honored in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | May 6, 1990, Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | July 31, 2002, Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City by Pope John Paul II |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Guadalupe |

| Feast | December 9 |

| Attributes | tilma |

| Patronage | Indigenous Peoples |

St. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin[1] (1474–1548) is the first Roman Catholic indigenous American saint.[2] He is said to have been granted an apparition of the Virgin Mary on four separate occasions in December 1531 at the hill of Tepeyac, then outside but now well within metropolitan Mexico City. The Basilica of Guadalupe located at the foot of the hill of Tepeyac claims to possess Juan Diego's mantle or cloak (known as a tilma) on which an image of the Virgin is said to have been impressed by a miracle as a pledge of the authenticity of the apparitions. These apparitions and the imparting of the miraculous image (together known as the Guadalupe event, in Spanish "el acontecimiento Guadalupano") are the basis of the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe which is ubiquitous in Mexico, prevalent throughout the Spanish-speaking Americas, and increasingly widespread beyond.[3] As a result, the Basilica of Guadalupe is now the world's major centre of pilgrimage for Roman Catholics, receiving 22 million visitors in 2010, the vast bulk of whom were pilgrims.[4] Juan Diego was beatified in 1990, and canonized in 2002.

Biography

According to tradition, Juan Diego was an Indian born in 1474 in Cuauhtitlan,[5] and at the time of the apparitions he lived there or in Tolpetlac.[6] Although not destitute, he was neither rich nor influential.[7] His religious fervor, his artlessness, his respectful but gracious demeanour towards the Virgin Mary and the initially skeptical Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, as well as his devotion to his sick uncle and, subsequently, to the Virgin at her shrine – all of which are central to the tradition – are among his defining characteristics and testify to the sanctity of life which is the indispensable criterion for canonization.[8] He and his wife, María Lucía, were among the first to be baptized after the arrival of the main group of twelve Franciscan missionaries in Mexico in 1524.[9] His wife died two years before the apparitions, although one source (Luis Becerra Tanco, possibly through inadvertence) claims she died two years subsequent to them.[10] There is no firm tradition as to their marital relations. It is variously reported (a) that after their baptism he and his wife were inspired by a sermon on chastity to live celibately; alternatively (b) that they lived celibately throughout their marriage; and in the further alternative (c) that both nd (c) are presented together and not in the alternative. Alternatives (a) and (b) may not necessarily conflict with other reports that Juan Diego (possibly by another wife) had a son.[11] Intrinsic to the narrative is Juan Diego's uncle, Juan Bernardino; but beyond him, María Lucía, and Juan Diego's putative son, no other family members are mentioned in the tradition. At least two 18th century nuns claimed to be descended from Juan Diego.[12] After the apparitions, Juan Diego was permitted to live next to the hermitage erected at the foot of the hill of Tepeyac,[13] and he dedicated the rest of his life to serving the Virgin Mary at the shrine erected in accordance with her wishes.[14] The date of death (in his 74th year) is given as 1548.[15]

Main sources

The earliest notices of an apparition of the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac to an Indian (whether or not named "Juan Diego") are to be found in various annals which are regarded by Dr. Miguel León-Portilla, one of the leading Mexican scholars in this field, as demonstrating "that effectively many people were already flocking to the chapel of Tepeyac long before 1556, and that the tradition of Juan Diego and the apparitions of Tonantzin (Guadalupe) had already spread."[16] Others (including leading Nahuatl and Guadalupe scholars in the USA) go only as far as saying that such notices "are few, brief, ambiguous and themselves posterior by many years".[17] If correctly dated to the 16th century, the Codex Escalada - which portrays one of the apparitions and states that Juan Diego (identified by his indigenous name) died "worthily" in 1548 - must be accounted among the earliest and clearest of such notices.

After the annals, a number of publications arose:[18]

- Sánchez (1648) has a few scattered sentences noting Juan Diego's uneventful life at the hermitage in the sixteen years from the apparitions to his death.

- The Huei tlamahuiçoltica (1649), at the start of the Nican Mopohua and at the end of the section known as the Nican Mopectana, there is some information concerning Juan Diego's life before and after the apparitions, giving many instances of his sanctity of life.[19]

- Becerra Tanco (1666 and 1675). Juan Diego's town of origin, place of residence at the date of the apparitions, and the name of his wife are given at pages 1 and 2 of the 6th (Mexican) edition. His heroic virtues are eulogized at pages 40 to 42. Other biographical information about Juan Diego (with dates of his birth and death, of his wife's death, and of their baptism) is set out on page 50. On page 49 is the remark that Juan Diego and his wife remained chaste – at the least after their baptism – having been impressed by a sermon on chastity said to have been preached by Fray Toribio de Benevente (popularly known as Motolinía).

- Slight and fragmented notices appear in the hearsay testimony (1666) of seven of the indigenous witnesses (Marcos Pacheco, Gabriel Xuárez, Andrés Juan, Juana de la Concepción, Pablo Xuárez, Martín de San Luis, and Catarina Mónica) collected with other testimonies in the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666.[20]

- Chapter 18 of Francisco de la Florencia's Estrella de el norte de México (1688) contains the first systematic account of Juan Diego's life, with attention given to some divergent strands in the tradition.[21]

Guadalupe narrative

The following account is based on that given in the Nican Mopohua which was first published in Nahuatl in 1649 as part of a compendious work known as the Huei tlamahuiçoltica. No part of that work was available in Spanish until 1895 when – as part of the celebrations for the coronation of the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe in that year - there was published a translation of the Nican Mopohua dating from the 18th century. This translation, however, was made from an incomplete copy of the original. Nor was any part of the Huei tlamahuiçoltica republished until 1929, when a facsimile of the original was published by Primo Feliciano Velásquez together with a full translation into Spanish (including the first full translation of the Nican Mopohua), since when the Nican Mopohua, in its various translations and redactions, has supplanted all other versions as the narrative of preference.[22] The precise dates in December 1531 - as given below - were not recorded in the Nican Mopohua, but are taken from the chronology first established by Mateo de la Cruz in 1660.[23]

Juan Diego, as a devout neophyte, was in the habit of regularly walking from his home to the Franciscan mission station at Tlatelolco for religious instruction and to perform his religious duties. His route passed by the hill at Tepeyac. First apparition: at dawn on Saturday 9 December 1531 while on his usual journey, he encountered the Virgin Mary who revealed herself as the ever-virgin Mother of God and instructed him to request the bishop to erect a chapel in her honour so that she might relieve the distress of all those who call on her in their need. He delivered the request, but was told by the bishop (Fray Juan Zumárraga) to come back another day after he had had time to reflect upon what Juan Diego had told him. Second apparition, later the same day: returning to Tepeyac, Juan Diego encountered the Virgin again and announced the failure of his mission, suggesting that because he was "a back-frame, a tail, a wing, a man of no importance" she would do better to recruit someone of greater standing, but she insisted that it was he whom she wanted for the task. Juan Diego agreed to return to the bishop to repeat his request. This he did on the morning of Sunday 10 December when he found the bishop more compliant. The bishop, however, asked for a sign to prove that the apparition was truly of heaven. Third apparition: Juan Diego returned immediately to Tepeyac and, encountering the Virgin Mary reported the bishop's request for a sign; she condescended to provide one on the following day (11 December).[24]

By Monday 11 December, however, Juan Diego's uncle Juan Bernardino had fallen sick and Juan Diego was obliged to attend to him. In the very early hours of Tuesday 12 December, Juan Bernardino's condition having deteriorated overnight, Juan Diego set out to Tlatelolco to get a priest to hear Juan Bernadino's confession and minister to him on his death-bed. Fourth apparition: in order to avoid being delayed by the Virgin and embarrassed at having failed to meet her on the Monday as agreed, Juan Diego chose another route around the hill, but the Virgin intercepted him and asked where he was going; Juan Diego explained what had happened and the Virgin gently chided him for not having had recourse to her. In the words which have become the most famous phrase of the Guadalupe event and are inscribed over the main entrance to the Basilica of Guadalupe, she asked: "No estoy yo aqui que soy tu madre?" (Am I not here, I who am your mother?). She assured him that Juan Bernardino had now recovered and she told him to climb the hill and collect flowers growing there. Obeying her, Juan Diego found an abundance of flowers unseasonably in bloom on the rocky outcrop where only cactus and scrub normally grew. Using his open mantle as a sack (with the ends still tied around his neck) he returned to the Virgin; she re-arranged the flowers and told him to take them to the bishop. On gaining admission to the bishop in Mexico City later that day, Juan Diego opened his mantle, the flowers poured to the floor, and the bishop saw they had left on the mantle an imprint of the Virgin's image which he immediately venerated.[25]

Fifth apparition: the next day Juan Diego found his uncle fully recovered, as the Virgin had assured him, and Juan Bernardino recounted that he too had seen her, at his bed-side; that she had instructed him to inform the bishop of this apparition and of his miraculous cure; and that she had told him she desired to be known under the title of Guadalupe. The bishop kept Juan Diego's mantle first in his private chapel and then in the church on public display where at attracted great attention. On 26 December 1531 a procession formed for taking the miraculous image back to Tepeyac where it was installed in a small hastily erected chapel.[26] In course of this procession, the first miracle was allegedly performed when an Indian was mortally wounded in the neck by an arrow shot by accident during some stylized martial displays executed in honour of the Virgin. In great distress, the Indians carried him before the Virgin's image and pleaded for his life. Upon the arrow being withdrawn, the victim made a full and immediate recovery.[27]

Beatification and canonization

The modern movement for the canonization of Juan Diego (to be distinguished from the process for gaining official approval for the Guadalupe cult, which had begun in 1663 and was realized in 1754)[28] can be said to have arisen in earnest in 1974 during celebrations marking the four hundredth anniversary of the traditional date of his birth,[29] but it was not until January 1984 that the then Archbishop of Mexico, Cardinal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada, named a Postulator to supervise and coordinate the inquiry, and initiated the formal process for canonization.[30] The procedure for this first, or diocesan, stage of the canonization process had recently been reformed and simplified by order of Pope John Paul II.[31]

Beatification

The diocesan inquiry was formally concluded in March 1986,[32] and the decree opening the Roman stage of the process was obtained on 7 April 1986. When the decree of validity of the diocesan inquiry was given on 9 January 1987 (permitting the cause to proceed), the candidate became officially "venerable". The documentation (known as the Positio or "position paper") was published in 1989, in which year all the bishops of Mexico petitioned the Holy See in support of the cause.[33] Thereafter there was a scrutiny of the Positio by consultors expert in history (concluded in January 1990) and by consultors expert in theology (concluded in March 1990), following which the Congregation for the Causes of Saints formally approved the Positio and Pope John Paul II signed the relative decree on 9 April 1990. The process of beatification was completed in a ceremony presided over by Pope John Paul II at the Basilica of Guadalupe on 6 May 1990 when 9 December was declared as the feast day to be held annually in honour of the candidate for sainthood thereafter known as "Blessed Juan Diego Cuauthlatoatzin".[34] In accordance with the exceptional cases provided for by Urban VIII (1625, 1634) when regulating the procedures for beatification and canonization, the requirement for an authenticating miracle prior to beatification was dispensed with, on the grounds of the antiquity of the cult.[35]

Miracles

Notwithstanding the fact that the beatification was "equipollent",[36] the normal requirement is that at least one miracle must be attributable to the intercession of the candidate before the cause for canonization can be brought to completion. The events accepted as fulfilling this requirement occurred between 3 and 9 May 1990 in Querétaro, Mexico (precisely during the period of the beatification) when a 20 year old drug addict named Juan José Barragán Silva fell 10 meters head first from an apartment balcony on to a cement area in an apparent suicide bid. His mother Esperanza, who witnessed the fall, invoked Juan Diego to save her son who had sustained severe injuries to his spinal column, neck and cranium (including intra-cranial haemorrhage). Barragán was taken to hospital where he went into coma from which he suddenly emerged on 6 May 1990. A week later he was sufficiently recovered to be discharged.[37] The reputed miracle was investigated according to the usual procedure of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints:- first the facts of the case (including medical records and six eye-witness testimonies including those of Barragán and his mother) were gathered in Mexico and forwarded to Rome for approval as to sufficiency - which was granted in November 1994. Next, the unanimous report of five medical consultors (as to the gravity of the injuries, the likelihood of their proving fatal, the impracticability of any medical intervention to save the patient, his complete and lasting recovery, and their inability to ascribe it to any known process of healing) was received, and approved by the Congregation in February 1998. From there the case was passed to theological consultors who examined the nexus between (i) the fall and the injuries, (ii) the mother's faith in and invocation of Blessed Juan Diego, and (ii) the recovery, inexplicable in medical terms. Their unanimous approval was signified in May 2001.[38] Finally, in September 2001, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints voted to approve the miracle, and the relative decree formally acknowledging the events as miraculous was signed by Pope John Paul II on 20 December 2001.[39] The Catholic Church considers an approved miracle to be a Divinely-granted validation of the results achieved by the human process of inquiry which constitutes a cause for canonization.

Canonization

As not infrequently happens, the process for canonization in this case was subject to delays and obstacles of various kinds. In the instant case, certain interventions were initiated through unorthodox routes in early 1998 by a small group of ecclesiastics in Mexico (then or formerly attached to the Basilica of Guadalupe) pressing for a review of the sufficiency of the historical investigation.[40] This review, which not infrequently occurs in cases of equipollent beatifications,[41] was entrusted by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints (acting in concert with the Archdiocese of Mexico) to a special Historical Commission headed by the Mexican ecclesiastical historians Fidel González, Eduardo Chávez Sánchez, and José Guerrero. The results of the review were presented to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints on 28 October 1998 which unanimously approved them.[42] In the following year, the fruit of the Commission's work was published in book form by González, Chávez Sánchez and Guerrero under the title Encuentro de la Virgen de Guadalupe y Juan Diego. This served, however, only to intensify the protests of those who were attempting to delay or prevent the canonization, and the arguments over the quality of the scholarship displayed by the Encuentro were conducted first in private and then in public.[43] The main objection against the Encuentro was that it failed adequately to distinguish between the antiquity of the cult and the antiquity of the tradition of the apparitions; the argument on the other side was that every tradition has an initial oral stage where documentation will be lacking. The authenticity of the Codex Escalada and the question whether the Nican Mopohua is to be dated to the 16th or 17th century have a material bearing on the duration of the oral stage.[44] Final approbation of the decree of canonization was signified in a Consistory held on 26 February 2002 at which Pope John Paul II announced that the rite of canonization would take place in Mexico at the Basilica of Guadalupe on 31 July 2002,[45] as indeed occurred.[46]

Historicity debate

The debate over the historicity of St. Juan Diego and, by extension, of the apparitions and the miraculous image, is largely a discussion of the reliability of the various documentary sources (many of which are second-hand), and the value, if any, to be placed on an oral tradition which – depending on the view taken of the sources – was first written down either a decade or a century after the year (1548) when St. Juan Diego is said to have died. Fundamental objections to the historicity of the Guadalupe event, grounded in the silence of the very sources which – so it is argued – are those most likely to have referred to it, were raised as long ago as 1794 by Juan Bautista Muñoz and were expounded in detail by the renowned Mexican historian Joaquín García Icazbalceta in a confidential report dated 1883 commissioned by the then Archbishop of Mexico and first published in 1896. The silence of the sources is discussed in a separate section, below. The most prolific contemporary protagonist in the debate is Stafford Poole, an historian and Vincentian priest in the United States of America, who questioned the integrity and rigor of the historical investigation conducted by the Catholic Church in the interval between Juan Diego's beatification and his canonization.

Partly in response to these and other issues, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints (the body within the Catholic Church with oversight of the process of approving candidates for sainthood) reopened the historical phase of the investigation in 1998, and in November of that year declared itself satisfied with the results.[47] Following the canonization in 2002, the Catholic Church considers the question closed, but it is not precluded from reopening the investigation should positive evidence of falsification of sources or significant and material errors emerge. For a brief period in mid-1996 a vigorous debate was ignited in Mexico when it emerged that Guillermo Schulenburg, who at that time was 83 years of age and had been Abbot (or custodian) of the Basilica of Guadalupe since 1963, did not believe that Juan Diego was a historical person or (which follows from it) that it is his mantle which is conserved and venerated at the Basilica. That debate, however, was focussed not so much on the weight to be accorded to the historical sources which attest to Juan Diego's existence as on the propriety of Abbot Schulenburg retaining an official position which – so it was objected – his advanced age, allegedly extravagant life-style and heterodox views disqualified him from holding. Abbot Schulenburg's resignation (announced on 6 September 1996) terminated that debate.[48] The scandal, however, re-erupted in January 2002 when the Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli published in the Italian newspaper Il Giornale a confidential letter dated December 4, 2001 which Schulenburg (among others) had sent to Cardinal Sodano, the then Secretary of State at the Vatican, reprising reservations over the historicity of Juan Diego.[49]

Earliest published narrative sources for the Guadalupe event

Sánchez, Imagen de la Virgen María

The first written account to be published of the Guadalupe event was a theological exegesis hailing Mexico as the New Jerusalem and correlating Juan Diego with Moses at Mount Horeb and the Virgin with the mysterious Woman of the Apocalypse in chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation. Entitled Imagen de la Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe, Milagrosamente aparecida en la Ciudad de México (Image of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God of Guadalupe, who miraculously appeared in the City of Mexico), it was published in Spanish in Mexico City in 1648 after a prolonged gestation.[50] The author was a Mexican-born Spanish priest, Miguel Sánchez, who asserted in his introduction (Fundamento de la historia) that his account of the apparitions was based on documentary sources (few, and only vaguely alluded to) and on an oral tradition which he calls "antigua, uniforme y general" (ancient, consistent and widespread). The book is structured as a theological examination of the meaning of the apparitions to which is added a description of the tilma and of the sanctuary, accompanied by a description of seven miracles associated with the cult, the last of which related to a devastating inundation of Mexico City in the years 1629-1634. Although the work inspired panegyrical sermons preached in honour of the Virgin of Guadalupe between 1661 and 1766, it was not popular and was rarely reprinted.[51] Shorn of its devotional and scriptural matter and with a few additions, Sánchez' account was republished in 1660 by a Jesuit priest from Puebla named Mateo de la Cruz, whose book, entitled Relación de la milagrosa aparición de la Santa Virgen de Guadalupe de México (Account of the miraculous apparition of the Holy Image of the Virgin of Guadalupe of Mexico), was soon reprinted in Spain (1662), and served greatly to spread knowledge of the cult.[52]

Nican Mopohua

The second-oldest published account is known by the opening words of its long title: Huei tlamahuiçoltica ("The great event"). It was published in Nahuatl by the then vicar of the hermitage at Guadalupe, Luis Lasso de la Vega, in 1649. In four places in the introduction he announced his authorship of all or part of the text - a claim long received with varying degrees of incredulity because of the text's consummate grasp of a form of classical Nahuatl dating from the mid-16th century the command of which Lasso de la Vega neither before nor after left any sign.[53] The complete work comprises several elements including a brief biography of Juan Diego and, most famously, a highly wrought and ceremonious account of the apparitions known from its opening words as the Nican Mopohua ("Here it is told"). Despite the variations in style and content which mark the various elements, an exclusively textual analysis by three American investigators published in 1998 provisionally (a) assigned the entire work to the same author or authors, (b) saw no good reason to strip de la Vega of the authorship role he had claimed, and (c) of the three possible explanations for the close link between Sánchez's work and the Huei tlamahuiçoltica, opted for a dependence of the latter upon the former which, however, was said to be indicated rather than proved. Whether the role to be attributed to Lasso de la Vega was creative, editorial or redactional remains an open question.[54] Nevertheless, the broad consensus among Mexican historians (both ecclesiastical and secular) has long been, and remains, that the Nican Mopohua dates from as early as the mid-16th century and (so far as it is attributed to any author) that the likeliest hypothesis as to authorship is that Antonio Valeriano wrote it, or at least had a hand in it.[55] The Nican Mopohua was not reprinted or translated in full into Spanish until 1929, although an incomplete translation had been published in 1895 and Becerra Tanco's 1675 account (see next entry) has close affinities with it.[56]

Becerra Tanco, Felicidad de México

The third work to be published was written by Luis Becerra Tanco who professed to correct some errors in the two previous accounts. Like Sánchez a Mexican-born Spanish diocesan priest, Becerra Tanco ended his career as professor of astrology and mathematics at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico.[57] As first published in Mexico City in 1666, Becerra Tanco's work was entitled Origen milagroso del Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe ("Miraculous origin of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Guadalupe") and it gave an account of the apparitions mainly taken from de la Cruz' summary (see entry [1], above).[58] The text of the pamphlet was incorporated into the evidence given to a canonical inquiry conducted in 1666, the proceedings of which are known as the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666 (see next entry). A revised and expanded edition of the pamphlet (drawing more obviously on the Nican Mopohua) was published posthumously in 1675 as Felicidad de Mexico and again in 1685 (in Seville, Spain). Republished in Mexico in 1780 and (as part of a collection of texts) republished in Spain in 1785, it became the preferred source for the apparition narrative until displaced by the Nican Mopohua which gained a new readership from the Spanish translation published by Primo Velázquez in Mexico in 1929 (becoming thereafter the narrative of choice).[59] Becerra Tanco, as Sánchez before him, confirms the absence of any documentary source for the Guadalupe event in the official diocesan records, and asserts that knowledge of it depends on the oral tradition handed on by the natives and recorded by them first in paintings and later in an alphabetized Nahuatl.[60] More precisely, Becerra Tanco claimed that before 1629 he had himself heard "cantares" (or memory songs) sung by the natives at Guadalupe celebrating the apparitions, and that he had seen among the papers of Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (?1578-1650) (i) a "mapa" (or pictographic codex) which covered three centuries of native history, ending with the apparition at Tepeyac, and (ii) a manuscript book written in alphabetized Nahuatl by an Indian which described all five apparitions.[61] In a separate section entitled Testificación he names five illustrious members of the ecclesiastical and secular elite from whom he personally had received an account of the tradition – quite apart from his Indian sources (whom he does not name).[62]

Informaciónes Jurídicas de 1666

The fourth in time (but not in date of publication) is the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666 already mentioned. As its name indicates, it is a collection of sworn testimonies. These were taken down in order to support an application to Rome for liturgical recognition of the Guadalupe event. The collection includes reminiscences in the form of sworn statements by informants (many of them of advanced age, including eight Indians from Cuauhtitlán) who claimed to be transmitting accounts of the life and experiences of Juan Diego which they had received from parents, grandparents or others who had known or met him. The substance of the testimonies was reported by Florencia in chapter 13 of his work Estrella de el Norte de México (see next entry). Until very recently the only source for the text was a copy dating from 1737 of the translation made into Spanish which itself was first published in 1889.[63] An original copy of the translation (dated 14 April 1666) was discovered by Eduardo Chávez Sánchex in July 2001 as part of his researches in the archives of the Basilica de Guadalupe.[64]

de Florencia, Estrella de el Norte de México

The last to be published was Estrella de el Norte de México by Francisco de Florencia, a Jesuit priest. This was published in Mexico in 1688 and then in Barcelona and Madrid, Spain, in 1741 and 1785, respectively.[65] Florencia, while applauding Sánchez's theological meditations in themselves, considered that they broke the thread of the story. Accordingly, his account of the apparitions follows that of Mateo de la Cruz's abridgement.[66] Although he identified various Indian documentary sources as corroborating his account (including materials used and discussed by Becerra Tanco, as to which see the preceding entry), Florencia considered that the cult's authenticity was amply proved by the tilma itself,[67] and by what he called a "constant tradition from fathers to sons . . so firm as to be an irrefutable argument".[68] Florencia had on loan from the famous scholar and polymath Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora two such documentary sources, one of which - the antigua relación (or, old account) - he discussed in sufficient detail to reveal that it was parallel to but not identical with any of the materials in the Huei tlamahuiçoltica. So far as concerns the life of Juan Diego (and of Juan Bernardino) after the apparitions, the antigua relación reported circumstantial details which embellish rather than add to what was already known.[69] The other documentary source of Indian origin in Florencia's temporary possession was the text of a memory song said to have been composed by Don Placido, lord of Azcapotzalco, on the occasion of the solemn transfer of the Virgin's image to Tepeyac in 1531 – this he promised to insert later on in his history, but never did.[70]

Historicity arguments

Leaving aside any question as to the reality of supernatural events as such, the primary doubts about the historicity of Juan Diego (and the Guadalupe event itself) arise from the silence of those major sources who would be expected to have mentioned him, including, in particular, Bishop Juan de Zumárraga and the earliest ecclesiastical historians who reported the spread of the Catholic faith among the Indians in the early decades after the capture of Tenochtítlan in 1521. Despite references in near-contemporary sources which do attest a mid-16th century Marian cult attached to a miraculous image of the Virgin at a shrine at Tepeyac under the title of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and despite the weight of oral tradition concerning Juan Diego and the apparitions (which, at the most, spans less than four generations before being reduced to writing), the fundamental objection of this silence of core 16th century sources remains a perplexing feature of the history of the cult which has, nevertheless, continued to grow outside Mexico and the Americas. The first writer to address this problem of the silence of the sources was Francisco de Florencia in chapter 12 of his book Estrella de el norte de Mexico (see previous section), but it was not until 1794 that the argument from silence was presented to the public in detail by someone – Juan Bautista Muñoz – who clearly did not believe in the historicity of Juan Diego or of the apparitions. Substantially the same argument was publicized in updated form at the end of the 19th and 20th centuries in reaction to renewed steps taken by the ecclesiastical authorities to defend and promote the cult through the coronation of the Virgin in 1895 and the beatification of Juan Diego in 1990.[71]

The silence of the sources can be examined by reference to two main periods: (i) 1531-1556 and (ii) 1556-1606 which, for convenience, may loosely be termed (i) Zumárraga's silence, and (ii) the Franciscan silence. Despite the accumulation of evidence by the start of the 17th century (including allusions to the apparitions and the miraculous origin of the image),[72] the phenomenon of silence in the sources persists well into the second decade of that century, by which time the silence ceases to be prima facie evidence that there was no tradition of the Guadalupe event before the publication of the first narrative account of it in 1648. For example, Bernardo de Balbuena wrote a poem while in Mexico City in 1602 entitled La Grandeza Mexicana in which he mentions all the cults and sanctuaries of any importance in Mexico City except Guadalupe, and Antonio de Remesal published in 1620 a general history of the New World which devoted space to Zumárraga but was silent about Guadalupe.[73]

Zumárraga's silence

Period (i) extends from the date of the alleged apparitions down to 1556, by which date there first emerges clear evidence of a Marian cult (a) located in an already existing ermita or oratory at Tepeyac, (b) known under the name Guadalupe, (c) focussed on a painting, and (d) believed to be productive of miracles (especially miracles of healing). This first period itself divides into two unequal sub-periods either side of the year 1548 when Bishop Zumárraga died.

Post-1548

The later sub-period can be summarily disposed of, for it is almost entirely accounted for by the delay between Zumárraga's death on 3 June 1548 and the arrival in Mexico of his successor, Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar, on 23 June 1554.[74] During this interval there was lacking not only a bishop in Mexico City (the only local source of authority over the cult of the Virgin Mary and over the cult of the saints), but also an officially approved resident at the ermita – Juan Diego having died in the same month as Zumárraga, and no resident priest having been appointed until the time of Montúfar. In the circumstances, it is not surprising that a cult at Tepeyac (whatever its nature) should have fallen into abeyance. Nor is it a matter for surprise that a cult failed to spring up around Juan Diego's tomb at this time. The tomb of the saintly fray Martín de Valencia (the leader of the twelve pioneering Franciscan priests who had arrived in New Spain in 1524) was opened for veneration many times for more than thirty years after his death in 1534 until it was found, on the last occasion, to be empty. But, dead or alive, fray Martín had failed to acquire a reputation as a miracle-worker.[75]

Pre-1548

Turning to the years before Zumárraga's death, there is no known document securely dated to the period 1531 to 1548 which mentions Juan Diego, a cult to the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac, or the Guadalupe event. The lack of any contemporary evidence linking Zumárraga with the Guadalupe event is particularly noteworthy, but, of the surviving documents attributable to him, only his will can be said to be just such a document as might have been expected to mention an ermita or the cult.[76] In this will Zumárraga left certain movable and personal items to the cathedral, to the infirmary of the monastery of St. Francis, and to the Conceptionist convent (all in Mexico City); divided his books between the library of the monastery of St Francis in Mexico City and the guesthouse of a monastery in his home-town of Durango, Spain; freed his slaves and disposed of his horses and mules; made some small bequests of corn and money; and gave substantial bequests in favour of two charitable institutions founded by him - one in Mexico City and one in Veracruz.[77] Even without any testamentary notice, Zumárraga's lack of concern for the ermita at Tepeyac is amply demonstrated by the fact that the building said to have been erected there in 1531 was, at best, a simple adobe structure, built in two weeks and not replaced until 1556 (by Archbishop Montúfar, who built another adobe structure on the same site).[78] Among the factors which might explain a change of attitude by Zumárraga to a cult which he seemingly ignored after his return from Spain in October 1534, the most prominent is a vigorous inquisition conducted by him between 1536 and 1539 specifically to root out covert devotion among Indians to pre-Christian deities. The climax of the sixteen trials in this period (involving 27 mostly high-ranking Indians) was the burning at the stake of Don Carlos Ometochtli, lord of the wealthy and important city of Texcoco, in 1539 - an event so fraught with potential for social and political unrest that Zumárraga was officially reprimanded by the Council of the Indies in Spain and subsequently relieved of his inquisitorial functions (in 1543).[79] In such a climate and at such a time as that he can hardly have shown favour to a cult which had been launched without any prior investigation, had never been subjected to a canonical inquiry, and was focussed on a cult object with particular appeal to Indians at a site arguably connected with popular devotion to a pre-Christian female deity. Leading Franciscans were notoriously hostile to - or at best suspicious of - Guadalupe throughout the second half of the 16th century precisely on the grounds of practices arguably syncretic or worse. This is evident in the strong reaction evinced in 1556 when Zumárraga's successor signified his official support for the cult by rebuilding the ermita, endowing the sanctuary, and establishing a priest there the previous year (see next sub-section). It is reasonable to conjecture that had Zumárraga shown any similar partiality for the cult from 1534 onwards (in itself unlikely, given his role as Inquisitor from 1535), he would have provoked a similar public rebuke.[80]

The Franciscan silence

The second main period during which the sources are silent extends for the half century after 1556 when the then Franciscan provincial, fray Francisco de Bustamante, publicly rebuked Archbishop Montúfar for promoting the Guadalupe cult. In this period, three Franciscan friars (among others) were writing histories of New Spain and of the peoples (and their cultures) who either submitted to or were defeated by the Spanish Conquistadores. A fourth Franciscan friar, Toribio de Benevente (known as Motolinía), who had completed his history as early as 1541, falls outside this period, but his work was primarily in the Tlaxcala-Puebla area.[81] One explanation for the Franciscans' particular antagonism to the Marian cult at Tepeyac is that (as Torquemada asserts in his Monarquía indiana, Bk.X, cap.28) it was they who had initiated it in the first place, before realising the risks involved.[82] In due course this attitude was gradually relaxed, but not until some time after a change in spiritual direction in New Spain attributed to a confluence of factors including (i) the passing away of the first Franciscan pioneers with their distinct brand of evangelical millennarianism compounded of the ideas of Joachim de Fiore and Desiderius Erasmus (the last to die were Motolinía in 1569 and Andrés de Olmos in 1571), (ii) the arrival of Jesuits in 1572 (founded by Ignatius Loyola and approved as a religious order in 1540), and (iii) the assertion of the supremacy of the bishops over the Franciscans and the other mendicant Orders by the Third Mexican Council of 1585, thus signalling the end of jurisdictional arguments dating from the arrival of Zumárraga in Mexico in December 1528.[83] Other events largely impacting on society and the life of the Church in New Spain in the second half of the 16th century cannot be ignored in this context:- depopulation of the Indians through excessive forced labour and the great epidemics of 1545, 1576-1579 and 1595,[84] and the Council of Trent, summoned in response to the pressure for reform, which sat in twenty-five sessions between 1545 and 1563 and which reasserted the basic elements of the Catholic faith and confirmed the continuing validity of certain forms of popular religiosity (including the cult of the saints).[85] Conflict over an evangelical style of Catholicism promoted by Desiderius Erasmus - which Zumárraga and the Franciscan pioneers favoured - was terminated by the Catholic Church's condemnation of Erasmus' works in the 1550s. The themes of Counter-reformation Catholicism were strenuously promoted by the Jesuits, who enthusiastically took up the cult of Guadalupe in Mexico.[86]

The basis of the Franciscans' disquiet and even hostility to Guadalupe was their fear that the evangelization of the Indians had been superficial, that the Indians had retained some of their pre-Christian beliefs, and, in the worst case, that Christian baptism was a cloak for persisting in pre-Christian devotions.[87] These concerns are to be found in what was said or written by leading Franciscans such as fray Francisco de Bustamante (involved in a dispute on this topic with Archbishop Montúfar in 1556, as mentioned above);- fray Bernardino de Sahagún (whose Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España was completed in 1576/7 with an appendix on surviving superstitions in which he singles out Guadalupe as a prime focus of suspect devotions);- fray Jerónimo de Mendieta (whose Historia eclesiástica indiana was written in the 1590s);- and fray Juan de Torquemada who drew heavily on Mendieta's unpublished history in his own work known as the Monarquía indiana (completed in 1615 and published in Seville, Spain, that same year). There was no uniform approach to the problem and some Franciscans were less reticent than others. Bustamante publicly condemned the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe outright precisely because it was centred on a painting (allegedly said to have been painted "yesterday" by an Indian) to which miraculous powers were attributed,[88] whereas Sahagún expressed deep reservations as to the Marian cult at Tepeyac without mentioning the cult image at all.[89] Mendieta made no reference to the Guadalupe event although he paid particular attention to Marian and other apparitions and miraculous occurrences in Book IV of his history – none of which, however, had evolved into established cults centred on a cult object. Mendieta also drew attention to the Indians' subterfuge of concealing pre-Christian cult objects inside or behind Christian statues and crucifixes in order to mask the true focus of their devotion.[90] Torquemada repeated, with variations, an established idea that churches had been deliberately erected to Christian saints at certain locations (Tepeyac among them) in order to channel pre-Christian devotions towards Christian cults.[91]

Probative value of silence

Only when very particular conditions obtain can legitimate inferences be drawn from silence in contemporary sources.[92] The doubtful relevance of silence as to the Gudalupe event in certain documents from the time of Zumárraga has already been noted under section 6.2.2 above, and Miguel Sánchez himself preached a sermon in 1653 on the Immaculate Conception in which he cites chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation but makes no mention of Guadalupe.[93]

Pastoral significance of St. Juan Diego in the Catholic Church in Mexico and beyond

The evangelization of the New World

Both the author of the Nican Mopectana and Miguel Sánchez explain that the Virgin's immediate purpose in appearing to Juan Diego (and to don Juan, the seer of the cult of los Remedios) was evangelical – to draw the peoples of the New World to faith in Jesus Christ:-[94]"In the beginning when the Christian faith had just arrived here in the land that today is called New Spain, in many ways the heavenly lady, the consummate Virgin Saint Mary, cherished, aided and defended the local people so that they might entirely give themselves and adhere to the faith . . in order that they might invoke her fervently and trust in her fully, she saw fit to reveal herself for the first time to two [Indian] people here".

The continuing importance of this theme was emphasised in the years leading up to the canonization of Juan Diego. It received further impetus in the Pastoral Letter issued by Cardinal Rivera in February 2002 on the eve of the canonization, and was asserted by John Paul II in his homily at the canonization ceremony itself when he called Juan Diego "a model of evangelization perfectly inculturated" – an allusion to the implantation of the Catholic Church within indigenous culture through the medium of the Guadalupe event.[95]

Reconciling two worlds

"as a compassionate mother to you and yours, to my devotees, to those who should seek me for the relief of their necessities".By contrast, the words of the Virgin's initial message as reported in Nican Mopohua are, in terms, specific to all residents of New Spain without distinction, while including others, too:-[98]

"I am the compassionate mother of you and of all you people here in this land, and of the other various peoples who love me, who cry out to me . ."The special but not exclusive favour of the Virgin to the indigenous peoples is highlighted in Lasso de la Vega's introduction:-[99]

"you wish us your children to cry out to [you], especially the local people, the humble commoners to whom you revealed yourself"

At the conclusion of the miracle cycle in the Nican Mopectana, there is a broad summary which embraces the different elements in the emergent new society "the local people and the Spaniards [Caxtilteca] and all the different peoples who called on and followed her".[100]

The role of Juan Diego as both representing and confirming the human dignity of the indigenous Indian populations and of asserting their right to claim a place of honour in the New World is therefore embedded in the earliest narratives, nor did it thereafter become dormant awaiting rediscovery in the 20th century. Archbishop Lorenzana, in a sermon of 1770, applauded the evident fact that the Virgin signified honour to the Spaniards (by stipulating for the title "Guadalupe"), to the Indians (by choosing Juan Diego), and to those of mixed race (by the colour of her face). In another place in the sermon he noted a figure of eight on the Virgin's robe and said it represented the two worlds that she was protecting (the old and the new).[101] This aim of harmonising and giving due recognition to the different cultures in Mexico rather than homogenizing them was also evident in the iconography of Guadalupe in the 18th century as well as in the celebrations attending the coronation of the image of Guadalupe in 1895 at which a place was given to 28 Indians from Cuautitlán (Juan Diego's birthplace) wearing traditional costume.[102] The prominent role accorded indigenous participants in the actual canonization ceremony (not without criticism by liturgical purists) constituted one of the most striking features of those proceedings.[103]

Indigenous rights

To the spiritual and social significance of Juan Diego within the Guadalupe event, there can be added a third aspect which has only recently begun to receive explicit recognition, although it is implicit in the two aspects already discussed: namely, the rights of indigenous people to have their cultural traditions and way of life honoured and protected against encroachment. All three themes were fully present in the homily of Pope John Paul II at the canonization of Juan Diego on 31 July 2002, but it was the third which found its most striking expression in his rallying call: "¡México necesita a sus indígenas y los indígenas necesitan a México!" (Mexico needs the indigenous people, the indigenous people need Mexico).[104] In this regard, Juan Diego had previously been acclaimed at the beatification ceremony in 1990 as the representative of an entire people - all the indigenous who accepted the Christian Gospel in New Spain - and, indeed, as the "protector and advocate of the indigenous people".[105]

In the process of industrial and economic development that was observable in many regions of the world after the Second World War, the rights of indigenous peoples to their land and to the unobstructed expression of their language, culture and traditions came under pressure or were, at best, ignored. Industrialization (led by the petroleum industry) made the problem as acute in Mexico as elsewhere. The Church had begun to warn about the erosion of indigenous cultures in the 1960s, but this was generally in the context of "the poor", "the under-privileged", and "ethnic minorities", often being tied to land reform.[106] The Latin American episcopate, at its Second and Third General Conferences held at Medellin, Colombia (November, 1968) and at Puebla, Mexico (January 1979) respectively, made the transition from treating indigenous populations as people in need of special care and attention to recognising a duty to promote, and defend the dignity of, indigenous cultures.[107] Against this background, it was Pope John Paul II - starting with an address to the indigenous peoples of Mexico in 1979 - who raised the recognition of indigenous rights to the level of a major theme distinct from poverty and land reform. The first time he linked Juan Diego to this theme, however, was not on his first Apostolic journey to Mexico in 1979, but in a homily at a Mass in Popayán, Colombia, on 4 July 1986. Numerous Papal journeys to Latin America in this period were marked by meetings with indigenous peoples at which this theme was presented and developed.[108]

Also at about this time, the attention of the world community (as manifested in the UN) began to focus on the same theme, similarly re-calibrating its concern for minorities into concern for the rights of indigenous peoples. In 1982 the Working Group on Indigenous Populations of the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (then called Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities) was established by a decision of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, and in 1985 work began on drafting a declaration of rights (a process which lasted 22 years). In due course, 1993 was proclaimed the International Year of the World's Indigenous People. The following year, the United Nations General Assembly launched the International Decade of the World's Indigenous Peoples (1995-2004) and then, on 13 September 2007, it adopted a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[109]

References

- ↑ This is the official name of the Saint. See Biographical Note Vatican Information Service, July 31, 2002. The indigenous name Cuauhtlatoatzin means "the eagle that talks", or "the talking eagle": see John Paul II, homily at the canonization Mass, 31 July 2002.

- ↑ Rose of Lima (1586-1617) was the first American saint (beatified 1667, canonized 1671); Martin de Porres (1579-1639) was the first mestizo American saint (beatified 1837, canonized 1962); and Kateri Tekakwitha (1656-1680), a Mohawk-Algonquin woman who lived in New York State was the first indigenous American to be beatified (in 1980; she was canonized in 2012).

- ↑ See, e.g., remarks of Pope John Paul II in his 1997 Apostolic Exhortation, Ecclesia in America para. 11, regarding the veneration of Our Lady of Guadalupe as "Queen of all America", "Patroness of all America", and "Mother and Evangeliser of America"; cf. Sousa et al., p. 1. In May 2010, the church of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Makati, Manila, Philippines, was declared a national shrine by the bishops' conference of that country: Archdiocesan Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe declared National Shrine, website of Archdiocese of Manila.

- ↑ Guadalupe Shrine Hosts 6M for Feastday Weekend, Zenit news agency, December 13, 2010. For comparison, in 2000, the year of the Great Jubilee, 25 million pilgrims were reported by the Rome Jubilee Agency, Pilgrims to Rome Break Records in Year 2000, Zenit news agency, 1 January 2001, but in 2006 the city of Rome computed altogether 18 million visitors, many of whom were there for purely cultural reasons Vatican puts a squeeze on visitors, The Times online, January 6, 2007. Eight million were expected at Lourdes in 2008 (the 150th anniversary of the apparitions): Benedict XVI to Join Celebrations at Lourdes, Zenit news agency, November 13, 2007.

- ↑ Sources (2) and (5) give his age as 74 at the date of his death in 1548; his place of birth is reported by (3) and (5) and by Pacheco among the witnesses at (4)

- ↑ Source (2) says he was living in Cuauhtitlán at the time of the apparitions; (3) and (5) report Tulpetlac.

- ↑ Source (2) in the Nican Mopohua calls him "maçehualtzintli", or "poor ordinary person", but in the Nican Mopectana it is reported that he had a house and land which he later abandoned to his uncle so that he could take up residence at Tepeyac; (3) says "un indio plebeyo y pobre, humilde y candído" (a poor Indian commoner, humble and unaffected); (5) says he came of the lowest rank of Indians, of the servant class; but one of the witnesses in (4) - Juana de la Concepción - says his father was cacique (or headman) of Cuauhtitlán. Guerrero Rosado developed a theory that he was of noble birth and reduced circumstances (the poor prince theory); see Brading, pp.356f.

- ↑ All the sources dwell in more or less detail on his humility, sanctity, self-mortification and religious devotion during his life after the apparitions.

- ↑ "recently converted" - (1) and (3); baptized in "1524 or shortly thereafter" - (5).

- ↑ Sources (2), (4), and (5) agree she died two years before the apparitions, and all those who mention a wife (bar one of the three Indians who gave testimony in 1666 and who mentioned a wife) name her.

- ↑ Discussed at length by Francisco de Florencia, cap.18, n° 223, fol. 111r.

- ↑ Unpublished records of Convent of Corpus Christi in Mexico City: see Fidel González Fernández, appendix 4.

- ↑ Part of the capilla de los Indios in the Guadalupe precinct stands on what are said to be the foundations of this hermitage: see Parroquia de Indios, official website of the Basilica of Guadalupe, accessed February 11, 2011.

- ↑ 'See the reference to "sanctity of life", in the text above.

- ↑ e.g. Codex Escalada, and see note under the reference to his date of birth in the text.

- ↑ As quoted in Our Lady Of Guadalupe: Historical Sources, an unsigned article in L’Osservatore Romano, Weekly Edition in English, January 23, 2002, page 8.

- ↑ Sousa et al., p.1; cf. Poole (1995) pp.50-58 where it is conceded that the Codex Sutro, at least, "probably dates from 1530 to 1540" (ibid., p.57).

- ↑ A convenient summary synthesis of the narrative biographical sources is at Burkhart, pp. 33-39.

- ↑ The texts of these two biographical sources can be found in English in Sousa et al. (de la Vega at pp.113/115, and Sánchez at p.141).

- ↑ The burden of these testimonies (which focus on Juan Diego's marital status and/ or his sanctity of life) can be read in Poole (pp.130-134, critically analyzed at pp. 139-141) supplemented by Burkhart, p.35.

- ↑ It occupies eight folios and three lines of a ninth (nn.213-236, foll.106r.-114r.)

- ↑ Cf. Poole (1995) pp.117f; Brading, p. 324; for various other translations into Spanish and English see Sousa et al., note 4 on p.3

- ↑ See Brading, p.76, citing Cruz' commentary to his 1660 abridgement of Sánchez' Imagen de la Virgen María.

- ↑ This apparition is somewhat elided in the Nican Mopohua but is implicit in three brief passages (Sousa et al., pp. 75, 77, 83). It is fully described in the Imagen de la Virgen María of Miguel Sánchez published in 1648.

- ↑ Sánchez (ibid., pp.137f.) made a point of naming numerous flowers of different hues (roses, lilies, carnations, violets, jasmine, rosemary, broom – accounting for the various pigments eventually to manifest themselves on the tilma); according to the Nican Mopohua (ibid., p.79) the Virgin told Juan Diego he would find "various kinds of flowers" at the top of the hill which Juan Diego picked and brought back to her, although there is the intervening description of them (when Juan Diego arrived at the top of the hill and surveyed the flowers) as "different kinds of precious Spanish [Caxtillan] flowers". Florencia, in the account of the fourth apparition, three times (cap.5, n°33f., fol.13) repeats the phrase "(diversas) rosas y flores", and in the final interview with the bishop (cap.6, n°38, fol.15r.) says that there poured from the tilma "un vergel abreviado de flores, frescas, olorosas, y todavía húmedas y salpicadas del rocío de la noche" (a garden in miniature of flowers, fresh, perfumed and damp, splashed with nocturnal dew). In Becerra Tanco's version (p.18), the only flowers mentioned were "rosas de castilla frescas, olorosas y con rocío" (roses of Castile, fresh and perfumed, with the dew on them). It was Becerra's Tanco's version that imposed itself on the iconographic tradition.

- ↑ The date does not appear in the Nican Mopohua, but in Sanchez's Imagen.

- ↑ The procession and miracle are not part of the Nican Mopohua proper, but introduce the Nican Mopectana which immediately follows the Nican Mopohua in the Huei tlamahuiçoltica.

- ↑ Brading, p.132

- ↑ The Cristero roots of the movement in the previous half century are traced in Brading, pp. 311-314 and 331-335.

- ↑ Cardinal Rivera, Carta pastoral, nn. 22, 24; cf. Chávez Sánchez, Camino a la canonización, which reports that the first Postulator (Fr. Antonio Cairoli OFM) having died, Fr. Paolo Molinari SJ succeeded him in 1989. Both of these were postulators-general of the religious Orders to which they belonged (the Franciscans and Jesuits, respectively) and were resident in Rome. In 2001 Fr. Chávez Sánchez himself was appointed Postulator for the cause of canonization, succeeding Mgr. Oscar Sánchez Barba who had been appointed in 1999.

- ↑ The reform of the procedure was mandated by John Paul II in his Apostolic Constitution Divinus perfectionis Magister ("The Divine Teacher and Model of Perfection"), 25 January 1983, and was put into effect from 7 February 1983 pursuant to rules drawn up by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints: New Laws for the Causes of Saints.

- ↑ Cardinal Rivera, Carta Pastoral, n.24

- ↑ Chávez Sánchez, Camino a la canonización, which includes the text of a letter of 3 December 1989 from Archbishop Suárez Rivera of Monterrey, as president of the Mexican Episcopal Conference, to Cardinal Felici, Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints; for the publication of the Positio, see ibid., footnote 30.

- ↑ AAS 82 [1990] p.855.

- ↑ A similar case of "equipollent beatification", as it is called, occurred in the case of eleven of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, who were beatified (with numerous other such martyrs) in stages between 1888 and 1929, but who were canonized together in 1970: see Canonization of 40 English and Welsh Martyrs, by Paolo Molinari, SJ, L'Osservatore Romano, weekly edition in English, 29 October 1970.

- ↑ Addis and Arnold, A Catholic Dictionary, Virtue & Co., London, 1954 s.v. "canonization".

- ↑ The circumstances of the fall, the details the injuries, the mother's prayer and the medical assistance provided to her son, the prognosis and his sudden inexplicable recovery are detailed in Fidel González Fernández, appendix 5.

- ↑ Chávez Sánchez, Camino a la canonización.

- ↑ AAS 94 [2002] pp.488f.

- ↑ The first intervention was by letter sent on 4 February 1998 by Carlos Warnholz, Guillermo Schulenburg and Esteban Martínez de la Serna to Archbishop (later Cardinal) Giovanni Battista Re then sostituto for General Affairs of the Secretariat of State which, in fact, has no competency over canonizations; this was followed by a letter dated 9 March 1998 to Cardinal Bovone, then pro-prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, signed by the same three Mexican ecclesiastics as also by the historians Fr. Stafford Poole, Rafael Tena and Xavier Noguez; a third letter, dated 5 October 1998, was sent to Archbishop Re signed by the same signatories as those who had signed the letter of 9 March 1998. The texts of these letters are included as appendices to Olimón Nolasco.

- ↑ See: Canonization of 40 English and Welsh Martyrs, by Paolo Molinari, S.J., L'Osservatore Romano, Weekly Edition in English, 29 October 1970; it is normally handled through the Historical-Hagiographical Office of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

- ↑ Cardinal Rivera, Carta Pastoral, nn.29, 35-37; cf. Chávez Sánchez, Camino a la canonización. Baracs names the prominent Guadalupanist Fr. Xavier Escalada SJ (who had first published the Codex Escalada in 1995) and the renowned Mexican historian and Nahuatl scholar Miguel León-Portilla (a prominent proponent of the argument for dating the Nican Mopohua to the 16th century) as also participating, with others, in the work of the Commission.

- ↑ Further correspondence with Rome ensued, later leaked to the press and eventually published in full by (Fr. Manuel) Olimón Nolasco:- letters of 27 September 1999 to Cardinal Sodano, then Secretary of State, from the original three Mexican ecclesiastics who had initiated the correspondence; of 14 May 2000 to Archbishop (now Cardinal) Tarcisio Bertone, then secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith signed by those three again, as well as by the three historians who had co-signed the letter of 9 March 1998; and, finally, another letter to Sodano of 4 December 2001 from the same three Mexican ecclesiastics as well as from Fr. Olimón Nolasco, the main purpose of which was to criticize Cardinal Rivera for "demonizing" those who were opposed to the canonization. On all this correspondence, see Baracs.

- ↑ For the polemic, see: González Fernández, Fidel, Eduardo Chávez Sánchez, José Luis Guerrero Rosado; Olimón Nolasco; and Poole (2005). Brading (pp. 338-341, 348-360) and Baracs offer dispassionate views of the controversy. For a sympathetic review in Spanish of Encuentro, see Martínez Ferrer.

- ↑ AAS 95 [2003] pp.801-803

- ↑ See John Paul II, Homily at the canonization Mass, 31 July 2002.

- ↑ Disclosures from Commission Studying Historicity of Guadalupe Event, Zenit news agency, December 12, 1999.

- ↑ Dimitió Schulenburg, La Jornada, September 7, 1996; cf. Brading, pp. 348f.

- ↑ Insiste abad: Juan Diego no existió, Notimex, January 21, 2002.

- ↑ Sánchez claimed in 1666 to have been researching the topic for "more than fifty years", see Poole (1995), p.102.

- ↑ Brading, p.74; Poole (1995), p.109.

- ↑ Florencia, cap. XIV, n° 183, foll.89v. and 90r.; cf. Poole (1995) p.109, Brading, p. 76.

- ↑ e.g.,Sousa et al., pp. 46-47; Brading, p. 360.

- ↑ Sousa et al., pp. 5, 18-21, 47. Their conclusion (b) was foreshadowed by Poole (1995), p. 221 and accepted as proved by Brading, pp. 358-360 and Burkhart (2000, p.1), despite the qualified nature of the claims actually made by the authors. Poole (loc. cit.), speaks of Lasso's "substantial or supervisory authorship even if most of the work was done by native assistants".

- ↑ See sketch by Traslosheros citing Primo Feliciano Velázquez, Angel María Garibay and Miguel León Portilla, to whom can be added Eduardo O'Gorman and, from the 19th century, García Icazbalceta who (as others have done) linked it to the college of Santa Cruz at Tlatelolco (see Poole (1995), p.222).

- ↑ Poole (1995), p.117, and pp. 145, 148 where he calls it a paraphrase; cf. Brading, p.89 who speaks of it as a "translation".

- ↑ Poole (1995), pp. 143f; Brading, p.89; for his claim to be correcting errors in previous accounts, see p. viii of the prologue to the 1883 edition of Felicidad and ibid. p.24 where he calls his account "la tradicion primera, mas antigua y mas fidedigna" (the first, most ancient and most credible tradition). Among the alleged errors are those relating to Juan Diego's residence in 1531 (Tolpetlac, p.2), and the material of the tilma (said to be palm, not maguey, fibre, p. 42).

- ↑ Brading, p.81

- ↑ Brading, pp. 76, 89 and 95.

- ↑ 1883 edition, prologue, pp. vii and viii and p. 28 for the absence of official records; pp. 33-36 for records of the native traditions.

- ↑ For the "cantares" see p.38 of the 1883 edition; for reference to the native documents held by Alva, ibid., pp. 36f.

- ↑ 1883 edition, pp.44-48; the named sources included Pedro Ponce de León (1546-1626), and Gaspar de Prabez (1548-1628) who said he had received the tradition from Antonio Valeriano.

- ↑ See Poole (1995), p.138. He gives an abstract of the testimonies at ibid., pp.130-137.

- ↑ Chávez Sánchez (2002).

- ↑ It contains a reference to 1686 as the date when the work was still being composed (cap. XIII, n° 158, fol.74r.); for the dates of the 18th-century editions see The Philadelphia Rare Books & Manuscripts Company, online catalogue, accessed February 26, 2011. It was republished in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico in 1895. A paperback edition was published in 2010 by Nabu Press, Amazon online catalogue, accessed February 26, 2011.

- ↑ See Florencia, cap. XIV, n° 182, fol.89v.; n° 183, fol.89v.

- ↑ See ibid., cap. X passim, n°65-83, foll.26r.-35r.

- ↑ "la tradición constante de padres á hijos, un tan firme como innegable argumento", ibid., cap. XI, n° 84, fol.35v. (and cap. XI passim); cf. passages to similar effect at cap.XII, n° 99, fol.43v., cap. XIII, n° 152, fol.70v., etc.

- ↑ Ibid., cap. XIII §10.

- ↑ Florencia's treatment of the various documentary Indian sources for the Guadalupe event (capp. XIII §§8-10, XV, and XVI) is both confusing and not entirely satisfactory on several other grounds, including much of what is objected by Poole (1995) pp.159-162, and Brading, pp.104-107.

- ↑ Brading claims Florencia was the first writer to address the Franciscan silence: pp.103f.; for Muñoz, see ibid., pp.212-216; for the factionalism surrounding the coronation project between 1886 and 1895, see ibid., pp.267-287; for the Schulenberg affair in 1995/6, see ibid., pp.348f.

- ↑ The earliest known copy of the tilma is significant in this regard - a painting by Baltasar de Echave Orio, signed and dated 1606, reproduced as Plate 10 in Brading. On the acheiropoietic iconology, see Peterson, pp.130 and 150; also, Bargellini, p.86.

- ↑ On Balbuena, see Lafaye, pp.51-59 with 291; on de Remesal, see Poole (1995), p.94.

- ↑ See Enciclopedia Franciscana; Poole (1995) p.58

- ↑ Torquemada (no reference) cited by Brading at p.45; and see Enciclopedia Franciscana.

- ↑ See Poole (1995) on (i) the reports of proceedings at the nine ecclesiastical juntas held between 1532 and 1548, and (ii) the joint letter of 1537 sent by Zumárraga and his brother bishops to the Emperor Charles V, as to both of which Poole remarks "undue importance should not be attached to . . [their] failure to mention the apparitions", pp.37f.

- ↑ The will (dated 2 June 1548) was published in 1881 by García Icazbelceta in Don Fray Juan de Zumárraga, primer Obispo y Arzobispo de México, appendix, docc. 41-43 at pp.171-181, and it is summarily noticed in Poole (1995), pp.35f.

- ↑ For the first ermita, see Miguel Sánchez, Imagen at Sousa et al., p.141; for another reference to it, see a letter of 23 September 1575 from the viceroy (Martín Enríquez) to King Philip II quoted in Poole (1995), p.73. For Montúfar's adobe ermita, see Miranda Gódinez, pp.335, 351, 353. In 1562 it was allegedly "a mean and low building and so cheap that it is of very little value . . almost completely made of adobe and very low" (tan ruin y bajo edificio, y tan poco costoso que es de muy poco valor, y lo que está hecho por ser como es casi todo de adobes e muy bajo): Medrano, apéndice 2, at p.83. But, according to the Protestant English pirate Miles Philips, who saw it in 1568 on his way to Mexico City as a prisoner, the church was "very faire" and was decorated "by as many lamps of silver as there be dayes in the yeere, which upon high dayes are all lighted" (quoted in Brading, p.2).

- ↑ Lopez Don, pp.573f. and 605.

- ↑ The topic is explored in Lafaye, pp.239f. and, passim, chapters 3 "The Inquisition and the Pagan Underground", 8 "The First Franciscans", and 12 "Holy Mary and Tonantzin".

- ↑ Hence the attention he gives in Bk. III, cap.14 to the three martyr children of Tlaxcala: Cristobal, Antonio and Juan - beatified with Juan Diego in May 1990: see Homily of John Paul II at the beatification, 6 May 1990.

- ↑ See Lafaye, p.238; Franciscan acceptance of the cult as late as 1544 is implicit in the second Guadalupan miracle as related by Miguel Sánchez (see Sousa et al., pp.142f.)

- ↑ See ibid., pp.30-34, with 242; Phelan, passim.

- ↑ See Lafaye, pp.15f., 254; and Phelan, chapter 10, on the epidemics.

- ↑ On the cult of the saints (including "the legitimate use of images") see Conc. Trid., Sess. XXV, de invocatione, veneratione et reliquiis sanctorum, et sacris imaginibus in Denzinger Schönmetzer Enchiridion Symbolorum (edn. 32, 1963) §§1821-1825.

- ↑ See Brading, pp.327f. for a discussion of Edmundo O'Gorman's argument in his Destierro des sombras(1986) which seemingly addresses this point.

- ↑ See, e.g., Phelan, p.51; Lafaye, p.238; Poole (1995), at, e.g., pp.62, 68, 150 etc.

- ↑ See, Brading, pp.268-275.

- ↑ See Lafaye, pp.216f.; Brading, pp.214f.; and Poole (1995), p.78.

- ↑ Mendieta, Historia eclesiástica indiana, Bk. IV, capp. 24-28 for Marian apparitions etc.; Bk. III, cap.23 for Indians insinuating pre-Christian cult objects into churches.

- ↑ Monarquía indiana, Bk.X, cap.8, quoted at Poole (1995), pp.92f.

- ↑ See, e.g., the conditions elaborated by the 17th-century Church historian Jean Mabillon as summarised at Brading, p.182.

- ↑ For Sánchez' sermon, see Poole (1995) p.109; as to the lack of special significance to be attributed to many of the "silent" sources, see ibid., p.219.

- ↑ Sousa et al., p.97; for Sánchez, who writes of the "New World", see ibid.. p.143

- ↑ John Paul II, homily at the canonization, 31 July 2002, §3; cf. ibid., homily (in Spanish) at beatification of Juan Diego and four others, 6 May 1990, s.5; in Card. Rivera's Carta Pastoral, 26 February 2002, the third and longest section (§§ 58-120) is entitled "Juan Diego, as evangelist".

- ↑ Sousa et al., p.141

- ↑ ibid., p.132

- ↑ ibid., p.65

- ↑ ibid., p.57

- ↑ ibid., p.113

- ↑ For Lorenzana's oración of 1770, see de Souza, pp.738 and 744.

- ↑ See, e.g., Brading, plates 16 and 20 with brief discussion at p.178; on the indigenous presence at the coronation, see ibid. p.297

- ↑ cf. Inculturation at Papal Masses, John L. Allen, Jnr., National Catholic Reporter, 9 August 2002 and The Papal liturgist(an interview with the then Bishop Piero Marini), ibid., 20 June 2003.

- ↑ John Paul II, homily (in Spanish) at the canonization of Blessed Juan Diego, 31 July 2002, §4

- ↑ idem, homily (in Spanish) at the beatification of Juan Diego, 6 May 1990, §5.

- ↑ e.g. John XXIII, Enc. Mater et magistra (1961) Part 3, passim and Enc. Pacem in Terris (1963), 91-97, cf. 125; Second Vatican Council, Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, Gaudium et spes (1965), nn.57f., 63-65, 69, 71; Paul VI, Enc. Populorum progressio (1967), 10, 72; homily (in Spanish) at a Mass for Colombian rural communities, 23 August 1968

- ↑ See The Medellin Document, under Conclusions at Introduction, §2, and at Human promotion (Justice) §14, (Education) §3; and The Puebla Document, at §19.

- ↑ See meeting with Mexican indians at Cuilapan (29 January 1979); speech to Amazonian indians at Manaus, Brasil (10 July 1980); speech to indigenous people, Guatemala City (7 March 1983); speech at a meeting with indigenous people at the airport of Latacunga, Ecuador (31 January 1985); speech to Amazonian indians at [Iquitos, Peru] (5 February 1985); homily at a Mass with indigenous people at Popayán, Colombia (4 July 1986); speech at a meeting with indians in the Mission of "Santa Teresita" in Mariscal Estigarribia, Paraguay (May 17, 1988); message to the indigenous peoples of the American continent marking the 5th centenary of the beginning of the evangelization of the continent (12 October 1992); speech to indigenous communities at the sanctuary of Our Lady of Izamal, Yucatan, Mexico (11 August 1993); homily at a Mass attended by indigenous populations at Xoclán-Muslay, Mérida, Mexico (11 August 1993).

- ↑ See Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UN General Assembly, 23 September 2007; a brief history of the process is here.

Sources

Primary sources

- Acta Apostolicae Sedis (AAS) 82 [1990], 94 [2002], 95 [2003]; text in Latin only, available as download from Vatican website

- Becerra Tanco, Felicidad de México, 6th edn., México (1883) publ. under the title "Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe y origen de su milagrosa imagen", available as a download from Colección digital Universidad autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Benevente, Toribio de, Historia de los indios de Nueva España (1541), ed. José Fernando Ramírez, Mexico (1858), available as a download from cervantesvirtual website.

- Denzinger Schönmetzer, Enchiridion Symbolorum (edn. 32, 1963).

- Florencia, Francisco de la, Estrella de el norte de México [. . .], Mexico City (1688), available as a download from [Colección digital] Universidad autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Informaciones sobre la milagrosa aparición de la Santísima Virgen de Guadalupe, recibidas en 1666 y 1723, publ. by Fortino Hipólito Vera, Amecameca: Impr. Católica (1889), available as a download from Colección digital Universidad autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Lasso de la Vega, Luis, Huey tlamahuiçoltica [. . .], Mexico City (1649) text and Eng. trans. in Sousa et al., q.v.

- Mendieta, Jerónimo de, Historia eclesiástica indiana (1596, but not publ. until 1870), available as a download from Colección digital Universidad autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de, Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España (completed in 1576/7, but first publ. only as from 1829 onwards), available as a download from Colección digital Universidad autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Sánchez, Miguel, Imagen de la Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe, milagrosamente aparecida en la ciudad de México [. . .], Mexico City (1648), Eng, trans. (excerpts) in Sousa et al.., q.v. and transcript of Spanish text printed as appendix 1 to H.M.S. Phake-Potter, "Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe: la pintura, la leyenda y la realidad. una investigación arte-histórica e iconológica", Cuadernos de arté y iconografía, vol.12, n°24 (2003) monograph, pp. 265–521 at pp. 391–491. Download via www.fuesp.com/revistas/pag/cai24.pdf.

- Torquemada, Juan de, [Monarquía indiana], Seville, (1615), 2nd. edn., Madrid (1723), available as a download from Instituto de investigaciones históricas, UNAM, with introduction by Miguel León-Portilla (2010).

- Zumárraga, Juan de, Last will and testament published in: García Icazbelceta, Joaquín, Don Fray Juan de Zumárraga, primer Obispo y Arzobispo de México, (1881), appendix, docc. 41-43 at pp. 171–181, available as a download from Colección digital Universidad autónoma de Nuevo León.

Secondary sources

- Addis and Arnold, A Catholic Dictionary, Virtue & Co., London (1954).

- Baracs, Rodrigo, Querella por Juan Diego, La Jornada Semanal, n° 390 (August 25, 2002).

- Bargellini, Clara, Originality and invention in the painting of New Spain, in: "Painting a new world: Mexican art and life, 1521-1821", by Donna Pierce, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, Clara Bargellini, University of Texas Press (2004).

- Brading, D.A. "Mexican Phoenix, Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition across Five Centuries", Cambridge University Press (2001).

- Burkhart, Louise M., Juan Diego's World: the canonical Juan Diego, in: Sell, Barry D., Louise M. Burkhart, Stafford Poole, "Nahuatl Theater, vol. 2: Our Lady of Guadalupe", University of Oklahoma Press (2006).

- Chávez Sánchez, Eduardo (12 November 2001), Camino a la canonizacíon, online article, also (as to second part only) at Proceso de la beatificación y canonización de Juan Diego;

- Chávez Sánchez, Eduardo (2002), "La Virgen de Guadalupe y Juan Diego en las Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666, (con facsímil del original)", Edición del Instituto de Estudios Teológicos e Históricos Guadalupanos.

- Rivera, Norberto Cardinal, "Carta Pastoral por la canonización del Beato Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin" (26 February 2002) available as a download from the website of the Archdiocese of Mexico.

- de Souza, Juliana Beatriz Almeida, "La imagen de la Virgen de Guadalupe por Don Francisco Antonio De Lorenzana", in XIV Encuentro de Latinoamericanistas Españoles, Congreso Internacional 1810-2010: 200 años de Iberoamérica, pp. 733–746

- Fidel González Fernández, "Pulso y Corazon de un Pueblo", Encuentro Ediciones, México (2005).

- González Fernández, Fidel, Eduardo Chávez Sánchez, José Luis Guerrero Rosado, "El encuentro de la Virgen de Guadalupe y Juan Diego", Ediciones Porrúa, México (1999, 4th edn. 2001).

- Lafaye, Jacques, "Quetzalcóatl and Guadalupe" (1974), Engl. trans. University of Chicago Press (1976).

- Lopes Don, Patricia, "The 1539 Inquisition and Trial of Don Carlos of Texcoco in Early Mexico", Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 88:4 (2008), pp. 573–606.

- Martínez Ferrer, Luis, reseña de "El encuentro de la Virgen de Guadalupe y Juan Diego", Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia, vol. 9 (2000), University of Navarre, Pamplona, Spain, pp. 597–600.

- Medrano, E.R., Los negocios de un arzobispo: el caso de fray Alonso de Montúfar Estudios de Historia Novohispana, No. 012, enero 1992, pp. 63–83.

- Miranda Gódinez, Francisco, "Dos cultos fundantes: los Remedios y Guadalupe", El Colegio de Michoacán A.C. (2001).

- Olimón Nolasco, "La Búsqueda de Juan Diego", Plaza y Janés, México (2002) available online.

- Peterson, Jeanette Favrot, Canonizing a Cult: A Wonder-working Guadalupe in the Seventeenth Century, in: "Religion in New Spain", Susan Schroeder, Stafford Poole edd., University of New Mexico Press (2007).

- Phelan, John Leddy, "The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World", California University Press (1956, 2nd edn. 1970).

- Poole, Stafford, C.M. (1995), "Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531-1797", University of Arizona Press;

- Poole, Stafford, C.M. (2000), Observaciones acerca de la historicidad y beatificación de Juan Diego, publ. as appendix to Olimon, q.v;