Joule expansion

The Joule expansion is an irreversible process in thermodynamics in which a volume of gas is kept in one side of a thermally isolated container (via a small partition), with the other side of the container being evacuated. The partition between the two parts of the container is then opened, and the gas fills the whole container.

The Joule expansion is also called free expansion. The process is a useful exercise in classical thermodynamics, as it is easy to work out the resulting increase in entropy, the so-called entropy production. If the gas is not ideal, the process is more complex and is called the Joule–Thomson effect.[1][2][3]

This type of expansion is named after James Prescott Joule who used this expansion, in 1845, in his study for the mechanical equivalent of heat, but this expansion was known long before Joule e.g. by John Leslie, in the beginning of the 19th century, and studied by Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac in 1807 with similar results as obtained by Joule.[4][5]

Description

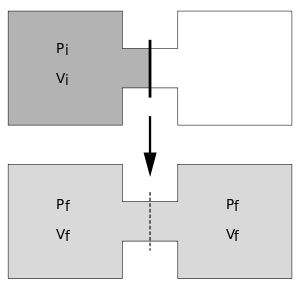

We consider n moles of an ideal gas at pressure Pi and temperature Ti, confined to the left-hand side (as drawn) of a thermally-isolated container, that occupies a volume Vi = V0. The right-hand side of the container, also with volume V0, is evacuated. The tap (solid line) between the two halves of the container is then suddenly opened and the gas fills the entire container of volume Vf = 2V0. We propose that both the previous and new temperature and pressure (Tf, Pf) follow the Ideal Gas Law, so that initially we have PiVi = nRTi and then, when the tap is opened, we have PfVf = nRTf, where R is the molar ideal gas constant.

As the system is thermally isolated, it cannot exchange heat with its surroundings. Also, since the system's volume is kept constant, the system does no work on its surroundings.[6] As a result, the change in internal energy ΔU = 0, and because U is a function of temperature only for the ideal gas, we know that Ti = Tf. This implies that PiV0 = Pf(2V0), and thus the pressure halves; i.e. Pf = ½Pi.

Entropy production

It is awkward to calculate the entropy production in this process directly, because the route that the expansion takes in the time between the partition being opened and the equilibrium state being reached involves states that are far from thermal equilibrium. However, entropy is a function of state, and therefore the entropy change can be computed directly from the knowledge of the final and initial equilibrium states. For an ideal monatomic gas, the entropy as a function of the internal energy U, volume V, and number of moles n is given by the Sackur–Tetrode equation:[7]

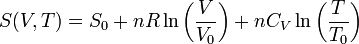

In this expression m the particle mass and h Planck's constant. For a monatomic ideal gas U = (3/2)nRT = nCVT, with CV the molar heat capacity at constant volume. In terms of classical thermodynamics the entropy of an ideal gas is given by

where S0 is the, arbitrary chosen, value of the entropy at volume V0 and temperature T0.[8] It is seen that a doubling of the volume at constant U or T leads to an entropy increase of ΔS = nR ln(2). This result is also valid if the gas is not monatomic, as the volume dependence of the entropy is the same as for all ideal gases.

One can also evaluate the entropy change by taking another route from the initial state to the final state, such that all the intermediary states are in equilibrium. Such a route can only be realized in the limit where the changes happen infinitely slowly. Such routes are also referred to as quasistatic routes. In some books one demands that a quasistatic route has to be reversible, here we don't add this extra condition. The net entropy change from the initial state to the final state is independent of the particular choice of the quasistatic route, as the entropy is a function of state.

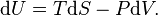

Suppose that, instead of letting the gas undergo a free expansion in which the volume is doubled, a free expansion in allowed in which the volume expands by a very small amount δV. After thermal equilibrium is reached, we then let the gas undergo another free expansion by δV and wait until thermal equilibrium is reached. We repeat this until the volume has been doubled. In the limit δV to zero, this becomes an ideal quasistatic process, albeit an irreversible one. Now, according to the fundamental thermodynamic relation, we have:

As this equation relates changes in thermodynamic state variables, it is valid for any quasistatic change, regardless of whether it is irreversible or reversible. For the above defined path we have that dU = 0 and thus TdS=PdV, and hence the increase in entropy for the Joule expansion is

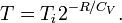

Another path that can be chosen is to let the system undergo a reversible adiabatic expansion in which the volume is doubled. The system will then perform work and the gas temperature goes down, so we'll have to supply heat to the system equal to the work performed to make sure it ends up in the same final state as in case of Joule expansion. During the reversible adiabatic expansion, we have dS = 0. From the classical expression for the entropy it can be derived that the temperature after the doubling of the volume at constant entropy is given as:

Heating the gas up to the initial temperature Ti increases the entropy by:

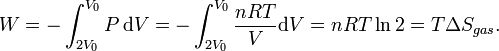

We might ask what the work would be if, once the Joule expansion has occurred, the gas is put back into the left-hand side by compressing it. The best method (i.e. the method involving the least work) is that of a reversible isothermal compression, which would take work W given by

During the Joule expansion the surroundings do not change, so the entropy of the surroundings is constant. So the entropy change of the so-called "universe" is equal to the entropy change of the gas which is nRln 2.

Real-gas effect

Joule performed his experiment with air at room temperature which was expanded from a pressure of about 22 bar. Air, under these conditions, is almost an ideal gas, but not quite. As a result the real temperature change will not be exactly zero. With our present knowledge of the thermodynamic properties of air [9] we can calculate that the temperature of the air should drop by about 3 degrees Celsius when the volume is doubled under adiabatic conditions. However, due to the low heat capacity of the air and the high heat capacity of the strong copper containers and the water of the calorimeter, the observed temperature drop is much lower, so Joule found that the temperature change was zero within his measuring accuracy.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joule/Gay-Lussac expansions. |

The majority of good undergraduate textbooks deal with this expansion in great depth; see e.g. Concepts in Thermal Physics, Blundell & Blundell, OUP ISBN 0-19-856770-7

- ↑ "Joule-Thomson-effect". The Editors of The Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "JOULE THOMSON EFFECT". Chemistry Department, Wright State University, Ohio. Retrieved 2103-12-31.

- ↑ "Joule–Thomson effect". wiki. ChemEngineering. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ D.S.L. Cardwell, From Watt to Clausius, Heinemann, London (1957)

- ↑ M.J. Klein, Principles of the theory of heat, D. Reidel Pub.Cy., Dordrecht (1986)

- ↑ Note that the fact that the gas expands in a vacuum and thus against zero pressure is irrelevant. The work done by the system would also be zero if the right hand side of the chamber were not evacuated, but is instead filled with a gas at a lower pressure. While the expanding gas would then do work against the gas in the right-hand side of the container, the whole system doesn't do any work against the environment.

- ↑ K. Huang, Introduction to Statistical Physics, Taylor and Francis, London, 2001

- ↑ M.W. Zemansky, Heat and Thermodynamics, McGraw-Hill Pub.Cy. New York (1951), page 177.

- ↑ Refprop, software package developed by National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

![S=nR\ln \left[\left({\frac VN}\right)\left({\frac {4\pi m}{3h^{2}}}{\frac UN}\right)^{{{\frac 32}}}\right]+{{\frac 52}}nR.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/8/1/a/881a14ec3da493736510cbe958019a25.png)