John Hall (poet)

| John Hall | |

|---|---|

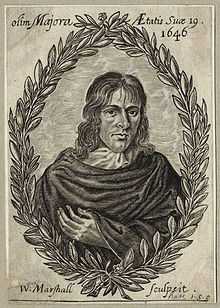

John Hall, 1646 engraving by William Marshall from Horæ Vacivæ. | |

| Born |

1627 Durham |

| Died | 1 August 1656 |

| Occupation | Pamphleteer |

| Nationality | British |

| Education |

St John's College, Cambridge; Gray's Inn |

| Genres | Poetry |

| Literary movement | Hartlib Circle |

John Hall (1627–1656) was an English poet, essayist and pamphleteer of the Commonwealth period. After a short period of adulation at university, he became a writer in the Parliamentary cause and Hartlib Circle member.[1]

Life

The son of Michael Hall, he was born at Durham in August 1627, was educated at Durham School, and was admitted to St John's College, Cambridge, on 26 February 1646.[2] Hall remained at Cambridge till May 1647, but considered his real merits unrecognised there. He later entered Gray's Inn.[3]

Hall was not initially against the monarchy; but his early views were reforming and utopian. He was much influenced by Baconianism and the chance of a renewal of learning.[4] Blair Worden describes Hall as "elusive" in the period from 1649, but points out parallels with the political development in the views of John Milton.[5]

By command of the Council of State he accompanied Oliver Cromwell in 1650 to Scotland. His friend John Davies states that Hall was awarded a pension of £100 per annum by Cromwell and the council for his pamphleteering services.[3]

Hall died on 1 August 1656, leaving unpublished works. Thomas Hobbes frequently visited him; another of his friends was Samuel Hartlib.[3]

Works

- Early works

At the age of nineteen Hall published Horæ Vacivæ, or Essays. Some occasional Considerations, 1646, which he dedicated to the master of his college, John Arrowsmith. Commendatory verses in English were prefixed;[6] Henry More contributed Greek elegiacs; and Hall's tutor, John Pawson, wrote a preface. A biographical notice in Hall's posthumous Hierocles, 1657 by his friend John Davies of Kidwelly declares that these essays made Hall's reputation international. Hall sent a copy to James Howell, whose letter of acknowledgment is printed in Epistolæ Ho-Elianæ. The essays were followed by a collection of poems published at Cambridge in January 1647; they were reprinted by Samuel Egerton Brydges in 1816. Commendatory verses by Henry More and others were prefixed, and the volume was dedicated to Thomas Stanley. The general title-page is dated 1646, but ‘The Second Book of Divine Poems’ has a new title-page dated 1647. Some of the divine poems were afterwards included in Emblems with Elegant Figures newly published. By J. H., esquire [1648], 2 parts, which was dedicated by the publisher to Mrs. Stanley (wife of Thomas Stanley), and has a commendatory preface by John Quarles.[3]

- Other literary work

In 1647 Hall edited Robert Hegge's In aliquot Sacræ Paginæ loca Lectiones. He contributed to the Lacrimae Musarum (1649) of Richard Brome.[7] The prose works of William Drummond of Hawthornden were published through the efforts of Sir John Scott of Scotstarvet, his brother-in-law, and Hall edited the History of Scotland (1655), writing a preface.[8][9] Other non-political writings were:

- ‘Paradoxes,’ 1650, second and enlarged edition in 1653; as "J. de La Salle".

- ‘Hierocles upon the Golden Verses of Pythagoras; Teaching a Vertuous and Worthy Life,’ posthumously published in 1657, with commendatory verses by Richard Lovelace and others.[3]

- Translations

In 1647 Hall translated from Latin for Hartlib two works of Comenius, as A Modell of a Christian Society and the Right Hand of Christian Love Offered.[10]

- A translation of ‘Longinus of the Height of Eloquence,’ 1652.

- ‘Lusus Serius, or Serious Passe-Time. A Philosophicall Discourse concerning the Superiority of Creatures under Man,’ 1654, translated from the Latin of Michael Maier, as "J. de La Salle".

At the time of his death he was engaged on a translation of Procopius.[3]

- Educational reform

An early work that remained in manuscript was A Method in History, discussing an education in history mainly in terms of classical authors.[9] In 1649, Hall published the tract An Humble Motion to the Parliament of England concerning the Advancement of Learning and Reformation of the Universities. In it he complains that the revenues of the universities are misspent and the course of study is too restricted; he advocates that the number of fellowships should be reduced and more professorships endowed.[3] The line taken was parallel with the writings of Milton and Hartlib on education. With his other works of the period, it helped catch the eye of the political agent Gualter Frost and forward his career as a state-paid writer.[11] Parts of the Method in History were used in the Advancement.[12] His views on the curriculum were practically-oriented and pansophist, closer to those of John Dury;[13] the model of Jesuit colleges was preferred to the existing colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, as far as rigour and discipline went.[14]

- Journalism

In 1648 Hall was writing the Mercurius Britanicus (sic) of the Second English Civil War, not the only time this title was used since there was a Mercurius Britanicus of the First English Civil War also, and the Mercurius Censorius, newsletters published in the Parliamentary interest. Journalism of this period was venal, and writers for hire, and he was paid by William Lilly the astrologer to further his verbal feud with George Wharton.[15] Hall's Mercurius Britanicus Alive Again was a response to the revived royalist Mercurius Aulicus, appeared from 16 May, and ran for 16 issues to August.[16] The rival to the Mercurius Britanicus was the Mercurius Pragmaticus of Marchamont Nedham (who, confusingly enough, had edited the first Mercurius Britanicus, but at this time was writing for the royalists). Hall's writing style and Nedham's are judged very similar; and they are believed to have colluded covertly to take opposite points of view. By 1650 Hall and Nedham were both on the side of Parliament in their journalism, with Hall writing for Nedham's Mercurius Politicus.[17]

- Political writings

In 1648 he published A Satire against Presbytery. In Scotland he drew up The Grounds and Reasons of Monarchy, with an appendix of An Epitome of Scottish Affairs, printed at Edinburgh and reprinted at London.[3] His approach to political theory is close to Hobbes in De Cive.[18]

Other political pamphlets were

- A Gagg to Love's Advocate, or an Assertion of the Justice of the Parliament in the Execution of Mr. Love, 1651, on Christopher Love;

- Answer to the Grand Politick Informer, 1653, against John Streater; and

- A Letter from a Gentleman in the Country, 1653;[3] this was a piece of apologetics on behalf of Oliver Cromwell and his dissolution of the Rump Parliament.[19]

The Discoverer has been attributed to Hall or John Canne.[20] It was a two-part attack in 1649 on the leadership of the Levellers, and is presumed to have been backed by the Council of State.[21]

He also put forth a new edition, dedicated to Cromwell, of A Treatise discovering the horrid Cruelties of the Dutch upon our People at Amboyna, 1651, which had originally appeared in 1624; the Dutch ambassador complained about this rehash of the Amboyna massacre. [3]

Notes

- ↑ Barbara Lewalski, The Life of John Milton (2003), p. 210.

- ↑ "Hall, John (HL645J2)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Bullen 1890.

- ↑ David Norbrook, Writing the English Republic: poetry, rhetoric, and politics, 1627-1660 (2000), p. 169; Google Books.

- ↑ Worden, p. 285.

- ↑ By Thomas Stanley, William Hammond, James Shirley, and others.

- ↑ Krzysztof Fordonski, Casimir Britannicus. English Translations, Paraphrases, and Emulations of the Poetry of Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski. Revised and Expanded Edition (2010), p. 104; Google Books.

- ↑ Stevenson, David. "Scot, Sir John, of Scotstarvit". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24888. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Raymond & 2005 p. 274.

- ↑ Charles Webster, Samuel Hartlib and the Advancement of Learning (2010), p. 31; Google Books.

- ↑ Raymond, Joad. "Hall, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11969. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ Smith, p. 340.

- ↑ Webster, p. 56; Google Books.

- ↑ Webster, p. 59; Google Books.

- ↑ http://www.bartleby.com/217/1505.html

- ↑ Raymond & 2005 p. 62.

- ↑ Worden, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Smith, p. 188.

- ↑ Blair Worden, The Rump Parliament 1648-53 (1977), p. 353; Google Books.

- ↑ Christopher Hill, Milton and the English Revolution (1977), p. 224].

- ↑ Paulina Kewes, The Uses of History in Early Modern England (2006), p. 270; Google Books.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bullen, Arthur Henry (1890). "Hall, John (1627-1656)". In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 24. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 71–72.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bullen, Arthur Henry (1890). "Hall, John (1627-1656)". In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 24. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 71–72. - Raymond, Joad (2005). Google Books The Invention of the Newspaper: English newsbooks, 1641-1649. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199282340.

- Smith, Nigel (1997). Literature & Revolution in England, 1640-1660. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300071535.

- Webster, Charles (1970). Samuel Hartlib and the Advancement of Learning. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521077156.

- Worden, Blair (2007). Literature and Politics in Cromwellian England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199230822.