John Chichester (d.1569)

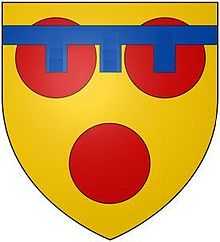

Sir John Chichester (1519/20-1569) of Raleigh in Devon, was a leading member of the Devonshire gentry, a naval captain, and ardent Protestant who served as Sheriff of Devon in 1550-1551, and as Knight of the Shire for Devon in 1547, April 1554, and 1563, and for Barnstaple in 1559.

Origins

The Chichester family had been seated at the manor of Raleigh since the mid-14th. century. He was the son of Edward Chichester (d. 27 July 1526) of Great Torrington, who predeceased his own father, by his wife Lady Elizabeth Bourchier (d.1548), whose small monumental brass exists in St Brannock's Church, Braunton, a daughter of John Bourchier, 1st Earl of Bath (1470–1539) whose seat was at Tawstock Court, 3 miles south of Raleigh. In the 16th and 17th centuries these two houses, Raleigh and the new Tawstock Court built in 1574, were probably the largest in North Devon.[1] He succeeded his grandfather in 1536.[2]

Career

As a young man he served in the Royal Navy, and in 1544 he was with King Henry VIII in France at the Siege of Boulogne. In 1545 he was captain of the ship Struce of Dansick under the command of Sir George Carew, a fellow Devonian. He was in London on the outbreak of the Western Rebellion in 1549, and set off back to Devon to fight for the royalist forces under the command of John Russell, 1st Baron Russell, who was probably responsible for recommending him to the king for Sheriff of Devon in 1550-1. As an expression of royal gratitude, Russell awarded Chichester jointly with Sir Arthur Champernon, the metal clappers which had been removed by royal command from Devon churchbells to prevent their being rung out by the rebels as calls to arms.

Following the death of King Henry VIII in 1547 he became an ardent supporter of the Duke of Somerset, the uncle of Henry's infant son King Edward VI, as Lord Protector. When Somerset was overthrown in 1551, Chichester was one of those temporarily imprisoned with him in the Tower of London.

When King Edward VI died in 1553, Chichester refused to support the Duke of Northumberland, Somerset's successor as Edward's chief minister, particularly not Northumberland's efforts to have his daughter-in-law Lady Jane Grey proclaimed Queen. He joined his cousin John Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Bath in being amongst the first to defy Northumberland by proclaiming Queen Mary as monarch. The queen rewarded Chichester with a knighthood, which he received three days before the opening of the first parliament of her reign in 1553.

In 1555 he accompanied Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford on an embassy to the Imperial court at Brussels, and went on with him as far as Venice. Chichester was arrested in 1556 for his involvement in the Dudley conspiracy against Queen Mary and was again imprisoned in the Tower of London. He was soon released although remained under various restrictive controls.

After the death of Queen Mary and the accession of Queen Elizabeth I in 1558, Chichester returned to active local and national political activity until his death in 1569. In 1566 he assigned to the Mayor, Corporation and Burgesses of Barnstaple all his rights and interests in the Manor of Barnstaple.[3]

Marriage & progeny

He married Gertrude Courtenay, a daughter of Sir William Courtenay (1477–1535) of Powderham, 6th in descent from Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (d.1377), and whose own grandson William Courtenay (1527–1557) of Powderham became himself de jure 2nd Earl of Devon under the 1553 creation of that title. Surprisingly the arms of his wife do not appear amongst the many heraldic escutcheons shown on his monument in Pilton Church. He had by her seven sons and nine daughters,[4] the marriages of several of whom are shown on a heraldic panel on his monument in Pilton Church.

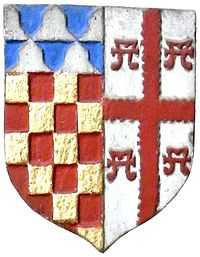

Heraldic Panel of Progeny

A heraldic panel from high up on the right side of the monument to Sir John Chichester (d. 1569) in Pilton Church shows his progeny and their marriage alliances. The first (leftmost, top row) representing the marriage of his eldest son and heir, shows Chichester impaling the Danish battle-axes of Denys of Holcombe Burnell. The remaining shields are all those of his daughters, with the arms of Chichester being impaled by the arms of the husband of each: l to r:

- row 1

- Denys

, Fortescue

, Basset

- row 2

- Bluett

, Dillon (Azure, a lion rampant between three crescents an estoile issuant from each gules over all a fess azure[5]), (???)

, Dillon (Azure, a lion rampant between three crescents an estoile issuant from each gules over all a fess azure[5]), (???) - row 3

- Pollard

, (???), (???)

Sons

- Sir John Chichester (d. 4/11/1597) of Raleigh, who married Anne Denys, daughter of Sir Robert Denys (d.1592), MP, of Holcombe Burnell. He was Governor of Carrickfergus, County Antrim, Ireland, and was captured and beheaded by Randal MacSorley Macdonnell.[6] He was father of Sir Robert Chichester (1579–1627), whose kneeling effigy and monument exists in Pilton Church, ancestor of the Chichester baronets .

- Arthur Chichester, 1st Baron Chichester (1563-1624/5), who succeeded his brother Sir John as Governor of Carrickfergus.

- Edward Chichester, 1st Viscount Chichester (1568–1648), of Eggesford, Devon.

Daughters

- Elizabeth Chichester (d.1630), married Hugh Fortescue (1544–1600), the son of Richard Fortescue (c.1517-1570) of Filleigh, ancestor of the Earls Fortescue. Effigies of the couple facing each other kneeling can be seen on the top tier of the mural monument in Weare Giffard Church erected by their grandson Hugh Fortescue (1592–1661).

- Cecilia Chichester, married Thomas Hatch

- Eleanor Chichester (d.1585), married Sir Arthur Bassett (1541-1586), MP, of Umberleigh and Heanton Punchardon, MP for Barnstaple in 1563 and for Devon in 1572.[7] He was the son of John Basset (son of Sir John Bassett (1462–1529) Sheriff of Devon in 1524) by his wife Frances Plantagenet, one of the three daughters and co-heiresses of Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (d.1542), an illegitimate son of King Edward IV. The couple's chest tomb with arms of Basset impaling Chichester on the slab-top exists in Atherington Church, in the parish of which is situated the manor of Umberleigh. The tomb was moved from the Basset Chapel which formerly existed next to Umberleigh House.

- Mary Chichester (d.1613), married Richard Bluett Esq. (d.1614) of Holcombe Rogus. The couple are represented as effigies on their monument in the Bluett Chapel, All Saints Church, Holcombe Rogus.

- Grace Chichester, married Robert Dillon of Farthington, Northamptonshire, son and heir of Henry Dillon of Bratton Fleming by his wife Elizabeth Pollard, daughter of Sir Hugh Pollard of Kings Nympton.[8]

- Dorothy Chichester, married Sir Hugh Pollard of King's Nympton, son and heir of Sir Lewis II Pollard of Kings Nympton.[9]

- Urith Chichester, married John Trevelyan of Nettlecombe in Somerset.

- Bridget Chichester, married Edmund Prideaux.

- Susannah Chichester, married firstly in 1580 (as his 2nd wife) John Fortescue Esq., MP, of Buckland Filleigh, with whom she had a son Sir Faithful Fortescue (d.1666).[10] She married secondly in 1584 William Fortescue.

Death & burial

Sir John Chichester died on 30 November 1569, and was buried in Pilton Church, in the parish of which, near Barnstaple in Devon, was situated his manor of Raleigh.

Monument in Pilton Church

A highly ornate monument exists against the east wall of the Raleigh Chapel in Pilton Church of St Mary the Virgin. It is decorated profusely with strapwork, but includes no effigy. On a tablet placed in its centre is inscribed the following Latin text:

O.nus Johannes Chichester Eques obiit 30th (sic) [11] Novembris 1569. Gertrudis (Courtenay) uxor eius obiit 30th (sic) Aprilis 1566. Ambo in spem Resurrectionis hic quiescunt. Ad lectorem:

Vana salus hominis tumideque simillima bulle,

Quam cito bulla cadit tam cito vita perit,

Dum vivis tu vive [12] deo nam vivere mundo,

Mortis opus vita est vivere vera deo,

Celica [13] terrenis prepone eterna caducis,

Perpetuum nihil est quod crevis hora rapit,

Sit tua firma fides pretioso in sanguine Christi,

Non aliunde tibi certa petenda salus,

Pectore non ficto si spem tibi junxeris istam,

Perpetuo dabitur non peritura quies.

Which may be translated literally as:

"John Chichester, knight, died the 30th of November 1569. Gertrude Courtenay his wife died the 30th of April 1566. Both rest here in hope of the Resurrection. To the reader:

The health of man is most like an empty and swollen bubble,

As quickly as the bubble falls so quickly perishes life,

Whilst you are alive live you in God! for to live in the world,

Life is the work of death to live in God is true life,

Place eternal heavenly things before perishable earthly ones,

Nothing is forever, what you grow the hour snatches away,

Let your faith be strong in the precious blood of Christ,

It is not fitting for you to seek sure health elsewhere,

Not with a brave look if you shall join to yourself that hope,

Rest not about to perish shall be given in perpetuity".

Sources

- Hawkyard, A.D.K., Biography of Sir John Chichester, published in History of parliament: House of Commons 1509-1558, Bindoff, S.T. (Ed.), London, 1982

- Chichester, Sir Alexander Bruce Palmer, Bart., History of the Family of Chichester from AD 1086 to 1870, published 1870, quoted in leaflet in Pilton Church. The author was Sir Alexander Palmer Bruce Chichester, 2nd Baronet (1842–1881), of the Chichester baronets, 1840 creation of Arlington Court.

References

- ↑ Reed, p.31, based on the hearth-tax return of 1664. The Earl of Bath also had a grand town-house just outside the South Gate of Barnstaple. (Lamplugh, Barnstaple: Town on the Taw, 2002, p.42)

- ↑ Hawkyard

- ↑ North Devon Record Office B1/1940 B1/3334 1566 Deed of Covenant

- ↑ Listed e.g. by Westcote, Thomas, A View of Devon

- ↑ Vivian, Heralds' Visitation of Devon 1620, p.284

- ↑ thepeerage.com

- ↑ History of Parliament Biography of Sir Arthur Basset

- ↑ Vivian, Heralds' Visitation of Devon, 1620, p.285

- ↑ Vivian, Heralds' Visitation of Devon, 1620, p.598

- ↑ http://thepeerage.com/p20597.htm#i205966

- ↑ In Latin this should be 30mo., abbreviated from tricensimo", "on the 30th."

- ↑ Dum vivis, homo, vive, nam post mortem nihil est, ("Live while you have the chance to live because after death there is nothing"), a Latin epitaph from a grave on the Appian Way in Rome, the last part omitted for a Christian context

- ↑ Celica a contraction of the adjective caeles-itis, "heavenly", thus caelitia ("heavenly things"), from caelum, "the heavens"