Jeton

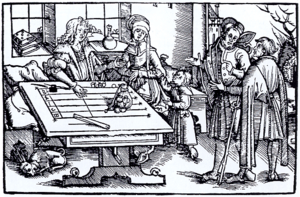

Jetons were token or coin-like medals produced across Europe from the 13th through the 17th centuries. They were produced as counters for use in calculation on a lined board similar to an abacus. They also found use as a money substitute in games, similar to modern casino chips or poker chips. Thousands of different jetons exist, mostly of religious and educational designs, as well as portraits, these most resembling coinage. (The spelling "jeton" is from the French; the English spell it "jetton".)

Roman calculi

The Romans had similarly used pebbles, in Latin "calculi" - little stones. Addition is straight forward, and relatively efficient algorithms for multiplication and division were known.

Arabic numerals

As Arabic numerals and the zero came into use, "pen reckoning" gradually displaced "counter casting" as the common accounting method. Jetons for calculation were commonly used in Europe from about 1200 to 1400, and remained in occasional use into the early nineteenth century.

The Late Middle Ages

Nuremberg, Germany, was in the Late Middle Ages an important center of production of jetons for commercial use. Later - "counter casting" being obsolete - the production shifted to jetons for use in games and toys, sometimes copying more or less famous jetons with a political background as the following.

In "the Nederlanden", the Low Countries, the respective mints in the late Middle Ages in general produced the counters for the official bookkeeping. These mostly show the effigy of the ruler within a flattering text and on the reverse the ruler's escutcheon and the name or city of the accounting office.

The 16th century onwards

During the Dutch Revolt (1568–1609) this pattern changed and by both parties, the North in front, about 2,000 different, mostly political, jetons (Dutch: Rekenpenning) were minted depicting the victories, ideals and aims. Specifically in the last quarter of the 16th century, where "Geuzen" or "beggars" made important military contributions to the Dutch side and bookkeeping was already done without counters, the production in the North was just for propaganda.

The mints and treasuries of the big estates in Central Europe used their own jetons and then had a number of them struck in gold and silver as New Year gifts for their employees who in turn commissioned jetons with their own mottoes and coats-of-arms. In the sixteenth century, the Czech Royal Treasury bought between two and three thousand pieces at the beginning of each year.

-

-

Gold jeton of Christoph Popel of Lobkowicz by David Engelhart, Prague 1592, diam 24 mm

Modern use

In the 21st century, Jetons continue to be used in some countries to denominate the substitutes for coins in coin-operated public telephones or vending machines, because automatic valuation of coins by machines is unreliable or impossible due to several factors. They are usually made of metal or hard plastic, and are generally called tokens in English-speaking countries.

In France and other countries, jeton is also a small (as a token, so to speak) amount of money paid to members of a society or a legislative chamber each time they are present in a meeting.

In the German language, the word Jeton refers specifically to casino tokens.

References

- Pullan, J. M. (1968). The History of the Abacus. London: Books That Matter. ISBN 0-09-089410-3.

- Menninger, Karl W. (1969). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13040-8.

- Bert, van Beek (1986). "Jetons: Their Use and History". Perspectives in Numismatics. Chicago Coin Club. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- Rouyer, Jules; Eugène Frédéric Ferdinand Hucher, Michel Pastoureau (1982). Histoire du jeton au Moyen âge.

- Kleisner, Tomáš; Zuzana Holečková (2006). Coins and Medals of the Last Rosenbergs. Prague: National Museum. ISBN 80-7036-206-5.

See also

| Look up jeton in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |