Jeju Uprising

| Jeju Uprising | |

|---|---|

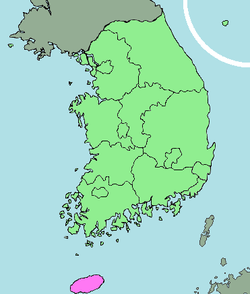

Map of South Korea with Jeju highlighted at the bottom in pink | |

| Location | Jeju Island, South Korea |

| Date | April 3, 1948 – May, 1949 |

| Target | Communists |

| Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | 14,000[1]–60,000, or one fifth of population killed from all fighting[2] |

| Perpetrators | Syngman Rhee anticommunist forces and sympathisers |

| Motive | White Terror, Fear of a North Korean Fifth column |

The Jeju Uprising (or the Jeju Massacre) was a communist revolt on Jeju island off the south coast of the Korean Peninsula, beginning on April 3, 1948. Between 14,000 and 60,000 individuals were killed in fighting between various factions on the island or were executed. The brutal suppression of this rebellion by the South Korean army resulted in many deaths, the destruction of many villages on the island, and more rebellions on the Korean mainland. The rebellion, which included the mutiny of several hundred members of the South Korean 11th Constabulary Regiment, lasted until May 1949, although small isolated pockets of fighting continued into September 21, 1954.[3][4][5] Up to 40,000 residents of Jeju escaped from the fighting to Japan.[6]

Background

On November 14, 1947, the United Nations passed UN Resolution 112, calling for a general election under the supervision of the UN Commission.[7] However, the Soviet Union refused to comply with the UN resolution and denied the UN Commission access to the northern part of Korea.[8] The USSR first held elections in the north, reporting a 99.6% turnout with 86.3% of voters supporting government backed candidates.[9]

Upset by the partition of the peninsula, the Communist Workers Party of South Korea planned rallies on March 1 to denounce and block the upcoming general elections scheduled for May 10.[citation needed] United States reports estimated that some 60,000 or 20% of the Jeju population were party members and a further 80,000 fellow travellers.[citation needed] The arrest of 2,500 party cadres, and the killing of at least three of them, broke up the planned demonstrations.[citation needed]

Shooting incident

On March 1, 1947, Jeju people firstly commemorated the Korean struggle against Japanese rule.[3] Secondly, they tried to denounce the South Korean Constitutional Assembly election scheduled for May 10, 1948.[3] Because Jeju people saw the election as unilateral attempt of the United States military government under the flag of United Nations to separate a southern regime and to employ its first president Syngman Rhee.[3] But police officers from the Korean peninsula fired on the crowd and killed six Jeju people.[3]

Rebellion

On April 3, 1948, the police on Jeju island fired on a demonstration commemorating the Korean struggle against Japanese rule.[1] Outraged, the people of Jeju attacked 12 police stations. In the fighting up to 100 policemen and civilians were killed. Rebels also burned polling centers for the upcoming election and attacked political opponents and their families.[5][10] They then issued an appeal urging the local population to rise against the American military government.

The Workers Party of South Korea and their appeal found sympathy among the local population due to the prevailing sentiment that the local government and police forces had collaborated with the Japanese occupation of Jeju and unrest caused by heavy taxation of agricultural commodities.[11]

Seeking a speedy resolution to the insurrection, the South Korean government sent 3,000 soldiers of the South Korean 11th Constabulary Regiment to reinforce local police, but on April 29 several hundred soldiers mutinied, handing over large small-arms caches to the rebels. The Seoul government also sent several hundred Northwest Youth Association members, a group of anti-communist North Korean refugees as part of a paramilitary force.[5] The Northwest Youth Association were notorious for the killing of male Jeju residents and then forcing the victim's female family members into marriage arrangements with Northwest Youth members so that they would inherit their land.[1]

Lieutenant General Kim Ik Ruhl, commander of the South Korean force on the island, attempted to end the insurrection peacefully by negotiating with the rebels. He met several times with rebel leader Kim Dalsam (South Korean Worker's Party Member) but neither side could agree on conditions. The government wanted what amounted to a complete surrender and the rebels demanded disarmament of the local police, dismissal of all governing officials on the island, prohibition of paramilitary youth groups on the island and re-unification of the Korean peninsula. General Kim Ik Ruhl was suddenly recalled to Seoul over his conciliatory approach with the rebels and was surprised when his replacement mounted a sustained offensive against the rebels by the end of the summer.[5]

The guerrillas created base camps in the mountains and the government forces held the coastal towns. Farming communities between the coast and the hills became the primary battle zone. By October 1948, the rebel army consisted of approximately 4,000 combatants, and although many were poorly armed, they scored a number of minor victories over the army. In late fall of 1948 the rebels began openly siding with the North Koreans by flying North Korean flags.[12]

On November 17, 1948, Syngman Rhee regime proclaimed a martial law in order to quell the rebellion.[3] One report from December 1948 describes how South Korean soldiers assaulted villages and took away young men and girls. The young men were executed, and girls were also executed after they had been gangraped over two weeks.[2]

American involvement

By spring of 1949 four South Korean Army battalions arrived and joined the local constabulary, police forces and Youth Association partisans. The combined forces quickly finished off most of the remaining rebel forces. On August 17, 1949, the leadership of the movement fell apart following the killing of major rebel leader Yi Tuk-ku.[12]

There was only a small number of Americans on the island during the uprising.[1] Jimmie Leach, then a captain in the American military, was an adviser to the South Korean Constabulary. He claims that there were six Americans on the island, including himself.[10] They could call on two small L-4 scout planes, and two old minesweepers converted to coastal cutters and manned by Korean crews.[10] It was only after the outbreak of the Korean War that the U.S. assumed command of the South Korean armed forces.[9] Carson Abel Roberts commanded Americans on Jeju.[13]

Reporters from Stars and Stripes provided vivid and uncensored accounts of the South Korean Army’s brutal suppression of the rebellion, the local popular support of the rebels as well as the rebels' retaliation against local “rightist” opponents.[citation needed] The Americans documented the massacre, but never intervened.[14] On May 13, 1949 the American ambassador to South Korea wired Washington that the Jeju rebels and their sympathizers had been, "killed, captured, or converted."[1]

During the Korean War

Immediately after the North Korean attack on South Korea which opened the Korean War, the South Korean military ordered "preemptive apprehension" of suspected leftists nationwide. Thousands were detained on Jeju, then sorted into four groups, labeled A, B, C and D, based on the perceived security risks each posed. On August 30, 1950, a written order by a senior intelligence officer in the South Korean Navy instructed Jeju's police to "execute all those in groups C and D by firing squad no later than September 6."[14] In March 1950, North Korea sent thousands of armed insurgents to resuscitate the guerrilla fighting on Jeju, but by this time the South Korean Army had become particularly adept at counterinsurgency and squashed the new insurgency in only a few weeks.

Aftermath

In one of its first official acts, the South Korean National Assembly passed the National Traitors Act in 1948, which among other measures, outlawed the Workers Party of South Korea.[15] For almost fifty years after the massacre it was a crime punishable by beatings, torture and a lengthy prison sentence if any South Korean even mentioned the events of the Jeju uprising.[1] The massacre had been largely ignored by the government. In 1992, President Roh Tae Woo's government sealed up a cave on Mount Halla where the remains of massacre victims had been discovered.[14] But after civil rule was later reinstated in the 1990s, the government made several apologies for the suppression, and efforts are being made to reassess the scope of the incident and compensate the survivors.

In October 2003, President Roh Moo-hyun apologized to the Jeju people for this massacre, stating, “Due to wrongful decisions of the government, many innocent people of Jeju suffered many casualties and destruction of their homes.”[3] Roh had made the first apology as South Korean president for the 1948 massacre.[3] In March 2009, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission confirmed its findings that "At least 20,000 people jailed for taking part in the popular uprisings in Jeju, Yeosu and Suncheon, or accused of being communists, were massacred in some 20 prisons across the country," when the Korean War broke out.[16]

The commission reported 14,373 victims, 86% at the hands of the security forces and 13.9% at the hands of armed rebels, and estimated that the total death toll was as high as 30,000.[17] Some 70 percent of the island's 230 villages were burned to the ground and over 39,000 houses were destroyed.[1] Before the uprising there had been 400 villages, after the suppression only 170 remained.[3] In 2008, bodies of massacre victims were discovered in a mass grave near Jeju International Airport.[3]

In Popular Media

Jiseul is 2012 film centering around Jeju residents during the uprising.

See also

- Bodo League massacre

- History of South Korea

- List of massacres in South Korea

- Korean War

- List of massacres

- Tamna

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Johnson, Chalmers. Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire (2000, rev. 2004 ed.). Owl Book. pp. 99–101. ISBN 0-8050-6239-4. According to Chalmers Johnson, death toll is 14,000-30,000

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Ghosts of Cheju". Newsweek. 2000-06-19. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Jung Hee, Song (March 31, 2010). "Islanders still mourn April 3 massacre". Jeju weekly. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ↑ O, John Kie-Chiang (1999). Korean Politics: The Quest for Democratization and Economic Development. Cornell University Press.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Deane, Hugh. The Korean War, 1945–1953 (October 1999 ed.). China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 0-8351-2644-7.

- ↑ Bruce Cumings (27 July 2010). The Korean War: A History. Random House Publishing Group. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-679-60378-8.

- ↑ "United Nations Resolution 112: The Problem of the Independence of Korea". United Nations. 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ↑ North Korea Through The Looking Glass.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Andreĭ Nikolaevich Lanʹkov". From Stalin to Kim Il Sung: the formation of North Korea, 1945-1960.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Col. Jimmie Leach, as told to Matt Hermes (January 10, 2006). "Col. Jimmie Leach, a former U.S. Army officer, recalls the Cheju-do insurrection in 1948". beaufortgazette. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ↑ Michael Breen. The Koreans: America's Troubled Relations with North and South Korea (December 28, 1999 ed.). Thomas Dunne Books. p. 304. ISBN 0-312-24211-5.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Michael J. Varhola. Fire and Ice : The Korean War, 1950-1953 (July 1, 2000 ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 317. ISBN 1-882810-44-9.

- ↑ "U.S. Gen. Roberts, center, back, commanded the operation in Jeju. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon". Jeju weekly. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 HIDEKO TAKAYAMA IN TOKYO (June 19, 2000). "Ghosts Of Cheju". newsweek. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Carter Malkasian. The Korean War (Essential Histories) (September 25, 2001 ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 2222. ISBN 1-84176-282-2.

- ↑ "Truth commission confirms civilian killings during war". Republic of Korea. 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-29. "At least 20,000 people jailed for taking part in the popular uprisings in Jeju, Yeosu and Suncheon, or accused of being communists, were massacred in some 20 prisons across the country."

- ↑ "The National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Jeju April 3 Incident". 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

Further reading

- Merrill, John (1989). Korea: The Peninsular Origins of the War. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-300-9. "Examines the local backdrop of the war, including large-scale civil unrest, insurgency and border clashes before the North Korean attack in June, 1950."

Coordinates: 33°22′N 126°32′E / 33.367°N 126.533°E