Jean-Baptiste Cope

| Jean-Baptiste Cope | |

|---|---|

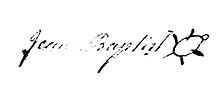

Signature of Jean Baptiste Cope (Beaver) | |

| Nickname | Major Cope |

| Born |

1698 Port Royal, Nova Scotia |

| Died |

October, 1758-1760 Miramichi, New Brunswick |

| Battles/wars |

|

Jean Baptiste Cope (Kopit in Mi’kmaq meaning ‘beaver’) was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq.[1] Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi'kmaq people of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia (Indian Brook 14, Nova Scotia/ Mi’kma'ki). He maintained close ties with the Acadians along the Bay of Fundy, speaking French and being Catholic.[2] During Father Le Loutre’s War, Cope participated in both military efforts to resist the British and also efforts to create peace with the British. During the French and Indian War he was at Miramichi, where he is presumed to have died during the war. Cope is perhaps best known for signing the 1752 Treaty with the British, which was upheld in the supreme court in 1985 (See R v. Simon) and is celebrated every year along with other treaties on Treaty Day (October 1).[3]

Father Rale's War

Cope was born in Port Royal and the oldest child of six.[4] During Father Rale's War, at the young age of 28, Cope was probably one of a number of Mi’kmaq who signed the peace treaty, which ended the war between the New Englanders and the Mi’kmaq.[5]

King William’s War

During King William's War, Cope was a leader in the Shubenacadie region. There were between 50-150 Mi’kmaq families and a few Acadian farms in the river valley close to the principal Mi’kmaq village named Copequoy. The village had become the site of a Catholic mission in 1722.[6] (The location became a site of two major annual events, All Saints Day and Pentecost, which attracted Mi’kmaq from great distances.[7])

Le Loutre took over the Shubenacadie mission in 1737. During King William’s War, Cope and Le Loutre worked together in several engagements against the British forces.[8]

Father Le Loutre’s War

At the outbreak of Father Le Loutre’s War, the Catholic missionary began to lead the Mi’kmaq and Acadian Exodus out of peninsular Nova Scotia to settle in French-ruled territory. Dozens of Mi’kmaq from Shubenacadie accepted Le Loutre’s offer and followed him to the Isthmus of Chignecto. But Cope and at least ninety other Mi’kmaq refused to abandon their homes on the Shubenacadie.[9] While Cope may have initially not supported the French initiatives, he would quickly reconsider after Edward Cornwallis establishing Halifax.

Cornwallis established Halifax in violation of early treaties with the Mi’kmaq.[10] He tried to set up peace treaties, but failed. Cornwallis offered to New England Rangers a bounty for the scalps of Mi’kmaq families just as the French had offered a bounty to the Mi’kmaq for the scalps of British families.[11] At the same time the British were adopting an uncomplicated, racially based view of local politics, several leaders of the Micmac community were developing a similar stance.[12] According to historian Geoffery Plank, both combatants understood their conflict as a "race war", and that the Mi’kmaq and British were “singlemindedly” determined to drive each other from the peninsula of Nova Scotia.[13]

After the establishment of Halifax, Cope seems to have joined Le Loutre at the Isthmus of Chignecto. Stationed in this region, through a series of raids, Cope and the other Mi’kmaq war leaders were able to confine the new settlers to the vicinity of Halifax.[14] British plans to scatter Protestants across peninsular Nova Scotia were temporarily undermined.[15]

Battle at Chignecto

After the Battle at Chignecto on September 3, 1750, Le Loutre and the French retreated to Beausejour ridge and Lawrence began to build Fort Lawrence on the former Acadian community of Beaubassin. Almost a month after the battle, on October 15, Cope, disguised in a French officer's uniform, approached the British under a white flag of truce and killed Captain Edward Howe.[16][17][18]

Peace Treaty (1752)

After eighteen months of inconclusive fighting, uncertainties and second thoughts began to disturb both the Mi’kmaq and the British communities. By the summer of 1751 Governor Cornwallis began a more conciliatory policy. For more than a year, Cornwallis sought out Mi’kmaq leaders willing to negotiate a peace. He eventually gave up, resigned his commission and left the colony.[19]

With a new Governor in place, Governor Peregrine Hopson, the first and only willing Mi’kmaq negotiator was Cope. On 22 November 1752, Cope finished negotiating a peace for the Mi’kmaq at Shubenacadie.[20] The basis of the treaty was the one signed in Boston which closed Father Rale's War (1725).[21] Cope tried to get other Mi’kmaq chiefs in Nova Scotia to agree to the treaty but was unsuccessful. The Governor became suspicious of Cope’s actual leadership among the Mi’kmaq people.[22] Of course, Le Loutre and the French were outraged at Cope’s decision to negotiate at all with the British.

Attack at Jeddore

In retaliation for the Attack at Country Harbour, on the night of April 21 (19 May), under the command of Major Cope, Mi'kmaq warriors attacked a diplomatic team made up of Captain Bannerman and his crew in the area of Jeddore, Nova Scotia. On board were nine English men and one Anthony Casteel, who was the pilot and spoke French. The Mi'kmaq killed the English and let Casteel off at Port Toulouse, where the Mi'kmaq sank the schooner after looting it.[23][24]

As the war continued, on 23 May 1753, Cope burned the peace treaty of 1752. The peace treaty signed by Cope and Hobson had not lasted six months. Shortly after, Cope joined Le Loutre again and worked to convince Acadians to join the exodus from peninsula Nova Scotia.[25]

After the experience with Cope, the British were less willing to trust Mi’kmaq efforts for peace that followed over the next two years. Future peace treaties also failed because the Mi’kmaq proposals always included land claims, which the British presumed was tantamount to giving land to the French.[26]

In the Action of 8 June 1755, a naval battle off Cape Race, Newfoundland, on board the French ships Alcide and Lys were found 10,000 scalping knives for Acadians and Indians serving under Chief Cope and Acadian Beausoleil as they continue to fight Father Le Loutre's War.[27]

French and Indian War

During the French and Indian War, Lawrence declared another bounty on scalps of male Mi’kmaq. Cope was probably among the Mi’kmaq and the Algonquian allies who helped Acadians evade capture during the St. John River Campaign.[28] According to Louisbourg account books, from 1756 to 1758, the French made regular payments to Cope and other natives for British scalps.[29] Cope is reported to have gone to Miramichi, New Brunswick, in the area where French Officer Boishebert had his refugee camp for Acadians escaping the deportation. He is likely to have died in the region before 1760.[30]

Legacy

After the treaty of 1752, while the conflict continued, the British never returned to their old policy of driving the Mi’kmaq off the peninsula.[31] The treaty signed by Cope and Governor Hobson has upheld in 1985 Supreme Court (See R v. Simon). Currently there is a monument to the Peace Treaty on the Shubenacadie Reserve (Indian Brook 14, Nova Scotia). The descendants of Cope gave Cope's gun to the Citadel Hill (Fort George) museum of Parks Canada.

Author Thomas Raddall wrote about Cope in his novel Roger Sudden.

See also

References

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.31

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.28

- ↑ "The Union of Nova Scotia Indians - Treaty Day". Union of Nova Scotia Indians. 1986-10-01. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.27

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.29

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.30

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.30

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.30

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.125

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.127

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.129

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.33

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.34

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.130

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.131

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.19

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.131

- ↑ There has long been uncertainty among scholars as to the identity of the person who shot Howe until Plank’s 2001 publication which cites , “Looking back on the incident years later, Cope claimed credit for killing the British officer p. 131. Also see Beamish Murdoch. A History of Nova Scotia. Vol. 2. p. 193

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.34

- ↑ Historian William Wicken notes that there is controversy about this assertion. While there are claims that Cope made the treaty on behalf of all the Mi'kmaq, there is no written documentation to support this assertion (See William Wicken. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Jr. University of Toronto Press. 2002. p. 184).

- ↑ For a detailed discussion of the treaty see William Wicken. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Jr. University of Toronto Press. 2002. pp. 183-189.

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.135

- ↑ Whitehead, p. 137

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.35

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.136

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.137

- ↑ Thomas H. Raddall. Halifax: Warden of the North. Nimbus. 1993. (originally 1948)p. 45

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.150

- ↑ Patterson, Stephen E. 1744-1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples. In Phillip Buckner and John Reid (eds.) The Atlantic Region to Conderation: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1994. p. 148

- ↑ Plank, 2001, p.152; also see Canadian Biography.

- ↑ Plank, 1996, p.37

Secondary sources

- Geoffrey Plank, “The Two Majors Cope: the boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18th Century Nova Scotia”, Acadiensis, XXV, 2 (Spring 1996), pp. 18–40.

- Geoffrey Plank. An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2001.

- John Mack Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005).

- William Wicken. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Jr. University of Toronto Press. 2002.

External links

- Diary of Anthony Casteel

- 1752 Peace Treaty

- Treaty Day - October 1

- Daniel Paul - Major Jean-Baptiste Cope

- Cope - Canadian Biography

- Major Cope - Film Short by Shawn Scott, Heroes and Hants Association