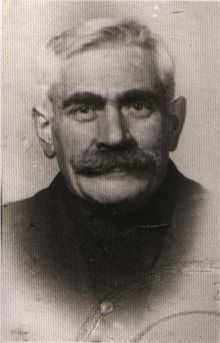

Jankiel Wiernik

| Jankiel Wiernik | |

|---|---|

Jankiel Wiernik | |

| Born |

1889 Biała Podlaska |

| Died |

1972 Rishon Lezion |

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||

| The Holocaust | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Camps

|

||||||||||

|

Resources |

||||||||||

|

Remembrance

|

||||||||||

Jankiel (or Yankel)-Yaakov Wiernik (in Hebrew: יעקב ויירניק; born 1889, Biala Podlaska, Poland; died 1972, Rishon Lezion, Israel)[1] was a Polish-Jewish Holocaust survivor who was an influential figure in the Treblinka extermination camp uprising of August 1943. Following his escape during the uprising, he published his account of his time in the camp, A Year in Treblinka, about his experiences and eyewitness testimony of that death camp where he witnessed the loss of anywhere from 700,000 to 900,000[2] innocent lives. Wiernik also testified in the Ludwig Fischer's trial in 1947, Eichmann Trial in 1961, and was present at the opening of the Treblinka Memorial in 1964. After World War II, Wiernik immigrated to Sweden and later moved to Israel where he died in 1972 at the age of 83.

Before Treblinka

Jankiel Wiernik was a janitor and carpenter living in Warsaw, Poland before his time in Treblinka. He was a member of the "self defence" of the "Bund" movement from 1904.[3] When World War II began, he was 50 years old.

A Year in Treblinka

Jankiel Wiernik published Rok w Treblince (A Year in Treblinka) in 1944 as a clandestine booklet printed through the efforts of Jewish National Committee, Bund (underground organisations of the remnants of Polish Jews) and Polish Council to Aid Jews Żegota by means of an underground printer organized by Ferdynand Arczyński. The circulation is estimated by Władysław Bartoszewski as 2000 copies. It was sent through Polish underground channels to London, translated into English and Yiddish and printed in USA by American Representation of the General Jewish Workers Union of Poland.[4] It was printed in Palestine by the "Histadrut in December 1944, translated into Hebrew by Icchak Cukierman.[3] The book recounts his experiences in the Treblinka concentration camp between 1942 and 1943.

Wiernik was transported to Treblinka on August 23, 1942 from Warsaw Ghetto.[4] On his arrival, Wiernik was selected to work rather than be immediately killed. Wiernik's first job required him to drag corpses from the gas chambers to mass graves. Wienik was traumatized by his experiences, writing 'It often happened that an arm or a leg fell off when we tied straps around them in order to drag the bodies away.'[5] Wiernik told of the horrors of the enormous pyres, where "10,000 to 12,000 corpses were cremated at one time." "The bodies of women were used for kindling" while Germans "toasted the scene with brandy and with the choicest liqueurs, ate, caroused and had a great time warming themselves by the fire."[6] Wiernik witnessed small children awaiting so long in the cold for their turn in the gas chambers that "their feet froze and stuck to the icy ground" and noted one guard who would "frequently snatch a child from the woman's arms and either tear the child in half or grab it by the legs, smash its head against a wall and throw the body away."[7] At other times "children were snatched from their mothers' arms and tossed into the flames alive." However, he was also encouraged by the occasional scenes of brave resistance.[8] In chapter 8, he describes seeing a naked woman escape the clutches of the guards and leap over a ten foot high barbed wire fence unscathed. When accosted by a Ukrainian guard on the other side, she wrestled his machine gun out of his grasp and shot two guards before being killed herself.

When Wiernik's profession as a carpenter was discovered, he was put to work constructing various camp structures including additional gas chambers. Given his skills, Wiernik was not subjected to the same treatment others were and he no longer had to handle dead bodies. Wiernik attributes his survival to his work building structures needed in the camp. Given the shortage of skilled construction workers, Wiernik moved between the two divisions of the camp frequently. As a result, Wiernik became an important figure, communicating between the camps when the revolt was being planned.

After Treblinka

Wiernik escaped Treblinka during the revolt of the prisoners on August 2, 1943, "a sizzling hot day." A shot fired into the air signalled that the revolt was on. Wiernik "grabbed some guns" and, after he saw an opportunity to make a break for the woods five miles away, an axe. A camp guard in hot pursuit shot Wiernik with a pistol but the bullet didn't penetrate his skin. Wiernik says he then turned around and dispatched his pursuer with the axe.[9] Wiernik continued on to Warsaw hiding in a freight train. He hid in Warsaw, secreted initially by the Polish family of Krzywoszewski, his former employers, who got for him false Kennkarte document by the name of Kowalczyk, and then by a woman named Bukowska. Next, Wiernik assumed the name of Jan Smarzyński. He made contact with members of Jewish underground working in the 'aryan' part of Warsaw and was recognised by them as a valuable eyewitness of the extermination procedures in Treblinka. He was persuaded in late 1943 to write A Year in Treblinka in spite of his initial reluctance (Wiernik had little education and was not a skilled writer). He continued to live in Warsaw (Wiernik's 'aryan' appearance allowed him to move relatively freely) and fought there in 1944 in Warsaw Uprising in the Armia Ludowa.[3][4] After the end of World War II, Wiernik initially remained in Poland (in 1947 he testified in the trial of Ludwig Fischer),[4] then immigrated to Sweden and afterwards to the newly founded state of Israel. In the 1950s, Wiernik built a model of the Treblinka camp which is displayed in the Ghetto Fighters' House museum in Israel. In 1961 Wiernik testified in the Eichmann trial in Israel.

Wiernik experienced the after-effects of his experience. His feeling of guilt can be seen in chapter one of A Year in Treblinka. "I sacrificed all those nearest and dearest to me. I myself took them to the place of execution. I built their death chambers for them." He stated that he had nightmares and had trouble sleeping. Apparently, the horrors he had experienced in Treblinka had caused him to suffer from survivor syndrome, a form of post-traumatic stress disorder.

See also

- Chil Rajchman, Treblinka revolt survivor, author of a parallel 1945 memoir The Last Jew of Treblinka

- Operation Reinhard, the most deadly phase of The Final Solution

- The Holocaust

- Treblinka

- Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jankiel Wiernik. |

References

- ↑ Ghetto Fighters' House Archives, Ya'akov Wiernik.

- ↑ Answers.com, Treblinka.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Lohami Ha'Gettaot Musium site (hebrow) Ghetto Fighters' House archives

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Władysław Bartoszewski Historia Jankiela Wiernika in Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej... p 633-634, available on-line

- ↑ A Year in Treblinka, chapter 3

- ↑ A Year in Treblinka, chapter 9

- ↑ A Year in Treblinka, chapter 7

- ↑ A Year in Treblinka, chapter 8

- ↑ A Year in Treblinka, chapter 14

- Yankel Wiernik (1945), A Year in Treblinka: An Inmate who Escaped Tells the Day-to-day Facts of One Year of His Torturous Experience (see scanned 1945 original in PDF format), New York: digitized by Zchor.org, OCLC 233992530, retrieved December 8, 2013, "Complete text, 14 chapters."

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|