James William Carling

James William Carling (1857–1887) was a pavement artist from Liverpool, England.

Carling was born at 38 Addison Street, Liverpool in the Holy Cross parish in 1857. He was the son of extremely poor Irish parents. From an early age James was known as the "little drawer" or "THE LITTLE CHALKER" and used Liverpool's street pavements for his art and to beg for money. Carling attended Holy Cross School.

In 1871, James William Carling (then aged 14) travelled to America to join his elder brother Henry and to attempt to become as successful an artist as Henry. When in America, James supported himself as a sidewalk artist and Vaudeville caricaturist before devoting his talents to illustrating the poem "The Raven". The poem's author, Edgar Allan Poe, Carling felt, was the "greatest poet this world has ever seen". Carling's drawings, created in the 1880s, are a graphic visual representation of the images Poe constructed in his poem. The Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia displays 43 of his illustrations of "The Raven" in what is known as "The Raven Room".

James Carling returned to Liverpool in 1887 with intentions to further his artwork and career. He died the same year and is buried in a Pauper's Grave at Walton Park Cemetery.

James William Carling is an important figure in the history of British pavement art;[1] to date, (2012) he is the earliest and the first pavement artist to be fully documented, with his life history recorded from birth to death.[2] As a child, he created something from nothing in an epic struggle against the grinding poverty of Victorian England; only to rise above his circumstances, and eventually make a successful career as a travelling artist in the USA.

Carling's life and times are celebrated annually in his birth town of Liverpool, England, with The James Carling International Pavement Art Competition.[3] This takes place on Bold Street, the very street where, as James Carling puts it, “I not only could not draw in that street, I could not walk in it.”[4]

JAMES CARLING IN LIVERPOOL

James and his brothers, Willy, Johnny and Henry had gone onto the streets at an early age as pavement artists. In their boyish ways they became political lampooners of the municipal government and were the delight of newsboys and street performers(buskers). But the pavement artists were the kings of the street Arabs, (neglected or homeless boys or girls). The police were no friends of theirs as they drove them off the streets in continuing warfare, but there were too many homeless and hungry children for the police to keep full control.

The Carling boys were big for their years in a town where many poor children had stunted growth through lack of proper nourishment. One of James memories was of a brutal struggle between his brother Johnny and a peeler (policeman) who clubbed the boy mercilessly.

Five-year-old James Carling, who had observed his older brothers practicing their street art, was given his chance to follow in their footsteps by Johnny when he gave him some paints and crayons. Early the following morning James made his way to Ranelagh Street in the town centre to claim the most suitable smooth flagstone to practice his art. His subjects that morning, were the prize-fighters, English champion Tom Sayers and Irish American champion John C. Heenan. Passers-by were so amused by the talent of one so young they started throwing coins into his little upturned hat and this encouragement drove him on. The streets of Liverpool were now the studio of little James Carling and the flagstones the canvas on which to display his works of art. James accepted guidance from his older brothers who were also street artists and he soon became well known, among other children and passers-by. Unlike most of the street artists in town he did not draw the same picture twice. Working his drawings onto the pavement had its pitfalls, as on rainy days, the rain could wash his enterprise away. At other times a policeman would beat him if he tried to practice his art on the streets used by the gentry.

Eventually James found the right spot on rainy days, under an arcade at the bottom of James Street, just a few hundred yards (metres) from where Liverpool’s Liver Building would be built many years later. This was not a good place to catch the eye of the wealthy toffs to throw a few coppers into the hat as most of his admirers were working men who had little or no money. They admired the young James who could produce such fine artwork on a paving stone. In return they would supply him with cockles, shrimps and periwinkles, or any other food they might have on them. Seamen were amongst his most generous benefactors and some days he would collect up to two shillings a day off them. Lime Street was another of his favourite thoroughfares; here was a never-ending flow of people of every shape and size. From the well-heeled, with their expensive attire, to the tramp with his battered boots, it was a shifting open theatre, a carousel that changed with the blink of an eye, of minstrels and acrobats, of bootblacks and pavement artists.

James Carling never forgot his boyhood on the streets of Liverpool. He would often recall his time spent in Ranelagh Street which was not free of policemen, who would often beat him although he was only six years of age:

“I knew I was too small to be incarcerated, for I was often arrested for drawing sidewalk pictures and taking their brutal beatings as a matter of course. I drew my pictures, preferring a bloody face and a bruised limb to inanition (exhaustion from want of food) and death by starvation”.James carried through life the contempt he felt for the well-heeled people of the town “Bold Street! My heart sickens at your name. And well it might, for I not only could not draw in that street I could not walk on it. The sight of a ragged coat was enough to bring the harsh ‘move on’ or what was worse, the most brutal application of the staff. On Bold Street, promenade of the aristocracy, the Gocking (pavement artist) did not draw”

On Christmas Eve, 1865, James had just reached his eighth birthday and made his way to Elliot Street to make some money for Christmas. It was a cold day and the biting wind was eating into his frail young body. As the day went on, he made his way to Lime Street, and no sooner had the young pavement artist started working than he felt the hands of a policeman as he was jerked to his feet. The young James Carling was dragged off to Cheapside Jail in the heart of the town.

He spent Christmas Eve in a police cell, then on Christmas Day he was transferred to the community workhouse for a week. It was then decided that James William Carling be ordered to spend six years in St. George’s Industrial School. The Headmaster at St’ George’s was Father Nugent a man who cared about the welfare of his young charges. The six years in the care of Father Nugent and his staff gave James Carling the opportunity to learn to read and write and the ability to express himself. James in later life never forgot what the school and Father Nugent did for him and when he returned to his school for a visit he was shown around by his old headmaster. A statue to Father Nugent, with his hand on the head of a young boy, stands in St. John’s Gardens, William Brown Street, Liverpool.[5]

JAMES CARLING IN AMERICA

James was released from Father Nugent’s Industrial School at the age of fourteen; His older brother Henry then took him to Philadelphia, in the United States of America, where they renewed their careers as sidewalk artists. A newspaperman took an interest in James and he became the subject of a feature story. The manager of a vaudeville troupe saw the article and contracted him to appear as the troupe’s Lightening Caricaturist. James later performed in a New York musical spectacular called. ‘The Black Crook’ where he appeared as a popular chalk/talk performer. The show took the young James all over America and during this time the boy from Liverpool was perfecting his art. After six years on the road with the musical spectacular, he joined his brother Henry in Chicago, where the latter had established a studio.

It was in Chicago, at the age of twenty-three, that James went in for a competition in Harper’s Magazine for illustrations for a special gift edition of The Raven a poem by Edgar Allan Poe. He entered thirty-three of the forty-three illustrations he had done in his brother’s studio in Chicago. However in 1883 Harper’s magazine announced to the world the winner of their competition. To illustrate “The most magnificent book of the year and in many cardinal particulars the most superb volume that has ever issued from the press of this or any other country the stately and luxurious folio, The Raven was by Gustave Dore”. He was a specialist in the bizarre and fantastic, whose editions of Paradise Lost, Divine Comedy, The Bible, the works of Balzac and others classic and contemporary works had made him the most popular and internationally famous illustrator of his century.

Fate had delivered a hammer blow to James Carling when it snatched away his chance to walk in the sun and leave behind the cold pavements of Liverpool. George F. Sheer in his research on James Carling wrote: “He returned to Europe, probably at this time to collect his grandfather’s songs and ballads. He returned to Liverpool in the spring of 1887 with the intention of studying at the National School of Art”. It is doubtful, however, that he even entered the school, for by the summer, James Carling became ill. His death was recorded as the 9th July 1887; he was 29 years of age.[6]

THE WORDS OF JAMES WILLIAM CARLING: From his unpublished Autobiography[7]

- "People prone to look upon the surface (and even the best judges of character, keenest of observers never see the life below the lower classes when occupying a niche or two above the class they would seek to hear about) are in utter ignorance concerning the desperate lives of the ragged children around them. They imagine because their accents are rough and their habits typical of the boxing den that their poverty and neglect of person are attributable to their innate ignorance and their natural depravity—but let one of them state that it is not their vulgarity. Refine and tone the boisterous gamin, give him the chances that your delicate aristocrats have, and the boy that dips his head in the mud for ha’penniers is not only the equal of your Norman descended scions but by the law of the fittest and the rule of the future, his superior in theory as well as in practice, and I know it!

- Alas for them, they have no champions; none have ever drawn the sword in defence of the prodigy in rags. His brain develops in an iron mask, no room nor show for the poverty stricken genius. Others with lesser minds usurp the place of the natural nobility and the bright sons of the streets cut off in a land where talents are smothered, sink down like the sun in the shadow of poverty and crime.

- Yet they shall be heard from in the bye and bye. This narrative—a still small voice, may herald the thunders of a future race and I launch this book like an old bottle upon the waters—to read when I am gone, when I have fretted my busy hour and am seen no more.”[8]

-

James Carling self-portrait as a child pavement artist, c.1880.

-

One of James Carling's illustrations for The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

-

Another James Carling illustrations for The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

-

Illustration for The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

-

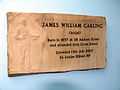

James Carling memorial plaque at Holy Cross School, Liverpool.

-

James Carling's unmarked grave at Walton Park Cemetery, Liverpool.

References

- ↑ http://www.urbancanvas.org.uk/james-carling-competition/

- ↑ James Carling illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven. ISBN 0-911303-03-0

- ↑ http://www.urbancanvas.org.uk/james-carling-competition/

- ↑ Liverpool's Irish Connection: ISBN 0955485401

- ↑ Liverpool's Irish Connection. ISBN 0955485401

- ↑ Liverpool's Irish Connection. ISBN 0955485401.

- ↑ James Carling illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven. ISBN 0-911303-03-0.

- ↑ James Carling illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven. ISBN 0-911303-03-0

- Liverpool Daily Post, 18 March 2008

- James Carling in his Own Words (1884)

- James William Carling - The Little Chalker!

- James Carling illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven. ISBN 0-911303-03-0.

- Liverpool's Irish Connection. ISBN 0955485401.

External links

- Scottie Press: James William Carling

- The James William Carling International Pavement Art Competition

- The Poe Museum

- ALL MY OWN WORK- A History of Pavement Art