James Smithson

| James Smithson | |

|---|---|

James Smithson by Henri-Joseph Johns, 1816 | |

| Born | ca. 1765 |

| Died | 27 June 1829 |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Nationality | English |

| Fields |

Chemistry Mineralogy |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Known for | Founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution |

James Smithson, MA, FRS (ca. 1765 – 27 June 1829) was a British chemist and mineralogist. He was the founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution.

Smithson was the illegitimate child of the 1st Duke of Northumberland, and was born secretly in Paris, as James Lewis Macie. Eventually he was naturalized in England and he attended college, studying chemistry and mineralogy. At the age of twenty-two, he changed his surname from Macie to Smithson, his father's surname.[1] Smithson traveled extensively throughout Europe publishing papers about his findings. Considered an amateur in his field, Smithson maintained an inheritance he acquired from his mother and other relatives. He was never married and had no children, therefore, when he wrote his will he left his estate to his nephew, or his nephew's family if his nephew died before Smithson. If his nephew was to die without a family, Smithson's will stipulated that he would donate his estate to the founding of an educational institution in Washington, D.C., in the United States. His nephew died and could not claim to be the recipient of his estate; therefore, Smithson became the founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He never visited the United States.

Early life

James Smithson was born about 1765 to Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland and Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie.[2] His mother was the widow of James Macie, a wealthy man from Weston, Bath.[3] An illegitimate child, Smithson was born in secret in Paris, making his exact birth date a mystery. His birth name was James Lewis Macie, and after the death of his parents he changed his last name to Smithson in 1801.[2][4] He was educated and eventually naturalized in England.[3] In 1766, his mother inherited Hungerfords of Studley, where her brother had lived up until his death.[5] Smithson enrolled at Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782 and graduated in 1786, later taking his MA.[6][7]

Smithson was nomadic in his lifestyle, traveling throughout Europe.[2] As a student, in 1784, he participated in a geological expedition with Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, William Thornton and Paolo Andreani of Scotland and the Hebrides.[8] He was in Paris during the French Revolution.[2] In August 1807 Smithson became a prisoner of war while in Tönning during the Napoleonic Wars. He arranged a transfer to Hamburg, where he was again imprisoned, now by the French. The following year, Smithson wrote to Sir Joseph Banks and asked him to use his influence to help free Smithson. Banks succeeded and Smithson returned to England.[9] He never married or had children.[2] Smithson's wealth stemmed from the splitting of his mother's estate with his half-brother, Col. Henry Louis Dickinson.[5]

Scientific work

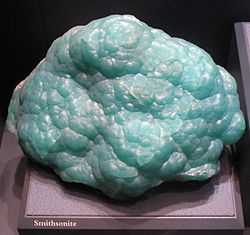

Smithson's research work was eclectic. He studied subjects ranging from coffee making to the use of calamine in making brass, which would eventually be called smithsonite. He also studied the chemistry of human tears, snake venom and other natural occurrences. Smithson would publish twenty-seven papers.[2] He was nominated to the Royal Society of London by Henry Cavendish and was made a fellow on April 26, 1787.[10] Smithson socialized and worked with scientists Joseph Priestley, Sir Joseph Banks, Antoine Lavoisier, and Richard Kirwan.[1]

His first paper was presented at the Royal Society on July 7, 1791, "An Account of Some Chemical Experiments on Tabasheer."[11] In 1802 he read his second paper, "A Chemical Analysis of Some Calamines," at the Royal Society. It was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London and was the documented instance of his new name, James Smithson. In the paper, Smithson challenges the idea that the mineral calamine is an oxide of zinc. His discoveries made calamine a "true mineral."[12] He explored and examined Kirkdale Cave and published about his findings in 1824. His findings successfully challenged previous beliefs that the fossils within the formations at the cave were from the Great Flood.[13] Smithson is credited with first using the word "silicates".[1]

Later life and death

Smithson died in Genoa, Italy on June 27, 1829.[2][14] He was buried in Sampierdarena in a Protestant cemetery.[14] In his will, Smithson left his fortune to his nephew, Henry James Hungerford.[5] In the will, which was written in 1826, Smithson stated that Hungerford or Hungerford's children would receive his inheritance, and if Hungerford did not live, and had no children to receive the fortune, he would donate it to the United States to have an educational institution called the Smithsonian Institution founded.[15] Hungerford died on June 5, 1835, unmarried and leaving behind no children, and the United States was the recipient.[15][16] In his will, Smithson explained the Smithsonian mission:

"I then bequeath the whole of my property, . . . to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men."[15]

Legacy and the Smithsonian

It was not until 1835 that the United States government was informed about the bequest. Aaron Vail wrote to Secretary of State John Forsyth.[17] This information was then passed onto President Andrew Jackson who then informed Congress. A committee was organized and the Smithsonian Institution was founded.[18] Smithson's estate was sent to the United States, accompanied by Richard Rush. The estate arrived as gold sovereigns in eleven boxes.[19][20] Smithson's personal items, scientific notes, minerals, and library also traveled with Rush.[19] The gold was transferred to the treasury in Philadelphia and was reminted into $508,318.46.[20] The final funds from Smithson were received in 1864 from Marie de la Batut, Smithson's nephew's mother. This final amount totaled $54,165.38.[21]

On February 24, 1847, the Board of Regents, who oversaw the creation of the Smithsonian, approved the seal for the institution. The seal, based on an engraving by Pierre Joseph Tiolier, was manufactured by Edward Stabler and designed by Robert Dale Owen.[22] Smithson's papers and collection of minerals were destroyed in a fire in 1865, however, his collection of 213 books remain intact at the Smithsonian.[2][23][24] The Board of Regents acquired a portrait of Smithson, which shows Smithson dressed in Oxford University student attire. The painting, by James Roberts, is now on display in the crypt at the Smithsonian Castle.[25] An additional portrait, a miniature, and the original draft of Smithson's will were acquired in 1877, which now reside in the National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian Institution Archives, respectively.[26] Additional items were acquired from Smithson's relatives in 1878.[27]

Relocation of Smithson's remains to Washington

Smithson was buried just outside of Genoa, Italy. The United States consul in Genoa was asked to maintain the grave site, with sponsorship for its maintenance coming from the Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Secretary Samuel P. Langley visited the site, contributing further money to maintain it and requested a plaque be designed for the grave site. Three plaques were created by William Ordway Partridge. One was placed at the grave site, a second at a Protestant chapel in Genoa, and the last was gifted to Pembroke College, Oxford. Only one of the plaques exists today. The plaque at the grave site was stolen and then replaced with a marble version. During World War II, the Protestant chapel was destroyed and the plaque was looted. A copy was eventually placed at the site in 1963.[23] The grave site itself was going to be relocated in 1905, and in response, Alexander Graham Bell, who was a regent for the Smithsonian, requested that Smithson's remains be moved to the Smithsonian Institution Building. In 1903, Bell and his wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, traveled to Genoa to exhume the body. The body set sail from Genoa on January 7, 1904 and arrived on January 20. On January 25, a ceremony was held and the body was escorted through Washington, D.C. by the United States Cavalry.[28] When handing over the remains to the Smithsonian, Bell stated:

"And now... my mission is ended and I deliver into your hands ... the remains of this great benefactor of the United States.”[28]

The coffin then lay in state in the Board of Regents' room, where objects from Smithson's personal collection were on display.[28]

Memorial

After the arrival of Smithson's remains, the Board of Regents asked Congress to fund a memorial. Artists and architects were solicited to create proposals for the monument. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Louis Saint-Gaudens, Gutzon Borglum, Totten & Rogers, Henry Bacon, and Hornblower & Marshall were some of the many artists and architectural firms who submitted proposals. The proposals varied in design, from elaborate monumental tombs that, if built, would have been bigger than the Lincoln Memorial, to smaller monuments just outside the Smithsonian Castle. Congress decided not to fund the memorial. To accommodate the fact that the Smithsonian would have to fund the memorial, they used the design of Gutzon Borglum, which suggested a remodel of the south tower room of the Smithsonian Castle to house the memorial surrounded by four Corinthian columns and a vaulted ceiling. Instead of the tower room, a smaller room at the north entrance, which was a children's museum, would house an Italian-style sarcophagus.[29]

On December 8, 1904, the Italian crypt was shipped, in sixteen crates from Italy. It traveled on the same ship that the remains of Smithson traveled on. Architecture firm Hornblower & Marshall designed the mortuary chapel, which included marble laurel wreaths and a neo-classical design. Smithson was entombed on March 6, 1905. His casket, which had been held in the Regent's Room, was carried down the spiral staircase of the Castle and placed into the ground underneath the crypt. This chapel was to serve as a temporary space for Smithson's remains until Congress approved a larger memorial. However, that never happened, and the remains of Smithson still lie there today.[30]

Ancestors

| 8. Sir Hugh Smithson, 3rd Bart., of Stanwick, (1657-1733) | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Langsdale Smithson | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Hon. Elizabeth Langdale | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland[31] | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. William Reveley of Newby Wiske (1662-1725) | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Philadelphia Reveley | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. Margery Willey | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. James Louis Macie Smithson | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. John Keate Esq. | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Lt. John Hungerford Keate Esq. (1709-c1755) | ||||||||||||||||

| 13. Frances Hungerford | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Elizabeth Hungerford Keate (1728-1800) | ||||||||||||||||

| 14. Henry Fleming DD, (1659-1728), Rector of Grasmere[32] | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Penelope Fleming (c1711-1764) | ||||||||||||||||

| 15. Mary Fletcher | ||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Colquhoun, Kate (31 May 2007). "A very British pioneer". The Telepgrah. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "James Smithson". Smithsonian History. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Goode, George Brown (1897). Birth of James Smithson. New York: De Vinne Press. pp. 1, 9.

- ↑ "James Macie Changes His Name to Smithson". Public Records Office, Great Britain. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C: De Vinne Press. p. 22.

- ↑ "James Smithson Enrolls at Oxford". Record Unit 7000, Box 5. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1880). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 10.

- ↑ "Smithson Held as a Prisoner of War". James Smithson Collection, 1796-1951. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: Di Vinne Press. pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century.. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835-1899, Vol. 1, 1835-1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 13.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. pp. 19–21.

- ↑ Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century.. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835-1899, Vol. 1, 1835-1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835-1899, Vol. 1, 1835-1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 125.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Goode, George Brown (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846-1896, The History of Its First Half Century. Washington, D.C.: De Vinne Press. p. 30.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Smithson's Legacy and Effects Arrive in NY". Chronology of Smithsonian History. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Rhees, William Jones (1901). The Smithsonian Institution: Documents Relative to Its Origin and History: 1835-1899, Vol. 1, 1835-1887. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Rhees, William J. (1879). Journals of the Proceedings of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1846-76, Reports of Committees, Statistics, Etc.. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 445–446.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Stamm, Richard E. "The Italian Grave Site". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington And the Search for a Proper Memorial. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "A Man of Science". From Smithson to Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Purchase of Smithson Portrait". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Smithson Portrait and Papers Purchased". Record Unit 7000, Box 3, Folder 7. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Smithson Artifacts Obtained from de la Batut". Record Unit 7000, p. Box 3, Folder 7. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Stamm, Richard E. "The Exhumation and Journey to America". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Stamm, Richard E. "The Search for a Proper Memorial". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Stamm, Richard E. "Smithson's Crypt". Mr. Smithson Goes to Washington. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Hugh Percy, 1st Duke of Northumberland". The Peerage. 27 January 2013.

- ↑ A genealogical history of the dormant, abeyant, forfeited, and extinct peerages of the British empire, Sir Bernard Burke, Harrison, 1866

Further reading

- Works by James Smithson

- Works about James Smithson

Articles

- Bird Jr., William L., William L. Bird, Jr. "A Suggestion Concerning James Smithson's Concept of 'Increase and Diffusion.'" Technology and Culture Vol. 24 No. 2 (April 1983): 246-255.

- Burleigh, Nina, "Digging Up James Smithson: Alexander Graham Bell traveled to Italy at the turn of the 20th century on an audacious mission to rescue the remains of the man whose legacy endowed the Smithsonian Institution," American Heritage, Summer 2012, Volume 62, Issue 2.

- CNN, "How a Mysterious Englishman's Fortune Founded the Smithsonian". 2000-05-08.

- Larner, Jesse (2003-12-21). "Foreign Motivations: How a Former President and an English Scientist Gave Us the Smithsonian (review of Nina Burleigh's The Stranger and the Statesman)". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Stamberg, Susan (2002-03-07). "The Smithsonian's Photographic History Project : Bringing Light to an American Institution's Photo Collection". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2007-06-19. Refers to a photograph, believed to have been taken by Alexander Graham Bell's wife, of an unidentified man holding the skull of James Smithson on the occasion of Alexander Graham Bell's mission to Genoa, Italy, in 1904 to retrieve Smithson's remains and bring them to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Books

- Bello, Mark; William Schulz, Madeleine Jacobs & Alvin Rosenfeld (eds.) (1993). The Smithsonian Institution, a World of Discovery : An Exploration of Behind-the-Scenes Research in the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities. Washington, D.C.: Distributed by Smithsonian Institution Press for Smithsonian Office of Public Affairs. ISBN 1-56098-314-0.

- Bolton, Henry Carrington (1896). The Smithsonian Institution : Its Origin, Growth, and Activities. New York, N.Y.

- Burleigh, Nina (2003). The Stranger and the Statesman : James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America's Greatest Museum, The Smithsonian. New York, N.Y.: Morrow. ISBN 0-06-000241-7 (hbk.) Check

|isbn=value (help). - Ewing, Heather (2007). The Lost World of James Smithson : Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. USA: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-59691-029-1 (hbk.) Check

|isbn=value (help). - Goode, George Brown (ed.) (1897). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896 : The History of its First Half Century. Washington, D.C. Reprinted as Goode, George Brown (ed.) (1980). The Smithsonian Institution, 1846–1896. New York, N.Y.: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-12584-4.

- Gurney, Gene (1964). The Smithsonian Institution, a Picture Story of its Buildings, Exhibits, and Activities. New York, N.Y.: Crown.

- Karp, Walter (1965). The Smithsonian Institution; an Establishment for the Increase & Diffusion of Knowledge among Men. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Rhees, William Jones (comp. & ed.) (1901). The Smithsonian Institution : Documents Relative to its Origin and History, 1835–1889. Washington, D.C.: G.P.O. Reprinted as Rhees, William Jones (ed.) (1980). The Smithsonian Institution, 1835–1899 (2 vols.). New York, N.Y.: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-12583-6.

External links

- Smithson's biographical details from the Royal Society of London

- Smithson's Library at the Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- James Smithson at LibraryThing by the Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- Remembering James Smithson from Around the Mall

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Smithson. |

|