James Croak

| James Croak | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | American |

| Field | conceptual configuration and sculpture |

| Training | University of Illinois[1] |

James Croak (born 1951) is a visual artist known for his work in conceptual figuration and sculpture.

Early Years

James Croak was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1951. His mother died at the age of two.[2] At the age of fifteen he was a recognized musical prodigy and studied under Andrés Segovia, the virtuoso Spanish classical guitarist.[3] At the age of sixteen he gave a series of concerts as a part of the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City.[4] Following his high school education, Croak attended the Ecumenical Institute in Chicago studying theology and philosophy,[5] and studied sculpture concurrently at the University of Illinois, graduating in 1974.[6]

Professional Life

Croak received a National Endowment for the Arts artist-in-residence grant in 1976. At this point much of his work was done with the medium of aluminum in a method similar to that of Frank Stella, although Croak is believed to have developed his personal technique himself.[7] Later that year he moved his work to the abandoned Fire Station Number 23 in Los Angeles, California, where his work became less abstract and more figural.[8] After eight years he moved to Brooklyn, New York.[9]

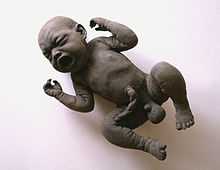

Croak’s work was featured in Thomas C. McEvilley’s book Sculpture in the Age of Doubt, and also in a book dedicated entirely to Croak’s work entitled James Croak, published by the same author. In 2011 he was featured at the Wellcome Collection in London, UK as a part of an exhibition entitled “Dirt”.[10] The work exhibited was designed to cause a strong emotional reaction in the onlooker: a review of his work at this show by The Guardian newspaper’s art critic Laura Cumming stated that, “It would be hard to overstate the physical effect of James Croak’s… sculpture”.[11] The sculpture was an example of his “dirt sculpture” technique, which employs a mixture of binder and different kinds of dirt, dust, and soil.[12] According to the artist, the material was developed out of necessity, stating that in 1985, “I wanted to cast a full-size self–portrait, but I couldn’t afford bronze, so I walked down the street to an empty lot, dug up dirt, put it in a wheelbarrow, took it home, mixed it with glue, and pressed it into the plaster mold.”[13] He has also been known to work with found objects[14] and taxidermy.[15] A twenty-year retrospective of his work was held in 1998 at the Contemporary Art Center of Virginia.[16]

The transition from aluminum to dirt as a medium gave his work a harder and rougher feel than his prior works.[12] In each medium Croak has designed his works in a series. Some examples of his series include the Dirt Man series, the Dirt Baby series, and the Dirt Window series.[12] Croak is also a published writer, with essays appearing in the books This Will Make You Smarter: New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking and Is the Internet Changing the Way you Think?: The Net’s Impact on our Minds and Future, both edited by John Brockman. An additional essay was published in the book Afterwords, a compilation put together by Salon.com featuring the works of its contributors, which Croak has been one on occasion.[17] He is also an online contributor and conference participant to the non-profit intellectual organization Edge.org,[18] the membership of which is composed of highly accomplished thinkers in both the arts and sciences from different corners of the world.[19] He is currently represented as an artist by Stux Gallery in New York City.[20][21] His works are also available at the website Artnet.[22] According to art critic Carlos Suarez de Jesus, themes involved in Croak’s work often include death, social instability, and the finite nature of human life.[23] Another recurring theme in his work is ancient mythology.[24] In addition, James Croak is an avid pilot and has an American commercial pilot license.

Dirt Sculpture

Croak’s dirt sculpture technique goes as follows. First a model is selected and photographed from many different angles. The photograph is then dressed with a grid in order to allow for accurate size referencing.[25] Second, an armature is created from steel and aluminum that is strong enough to support two hundred pounds of clay.[26] Third, the clay is sculpted in the presence of the model over the span of more than one hundred hours in order to replicate the model’s body as precisely as possible.[27] Fourth, smaller and more minute details like the face are refined.[28] Fifth, the sculpture is then cut into pieces and a two layer mold (a rubber layer and a plaster layer) is made from those pieces.[29] Sixth, Croak digs up or acquires a large amount of dirt and dries it with the aid of large fans.[30] Seventh, Croak mixes the dirt with a binder, then pours the mixture into the mold.[31] Eighth, once set, the pieces of the sculpture are then reassembled and glued together with the same dirt and binder mixture with which they were created.[32] His dirt sculptures have appeared in over twenty-five published books.[33]

External links

- http://www.jamescroak.com/ (Artist Site)

References

- ↑ "James Croak interview with Barbara Bloemik, Curatorial Director of the National Design Museum at the Smithsonian". Smithsonian. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Dirty Work". The Pitch. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Dirt: The Filthy Reality of Everyday Life—Review". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Supra note 1

- ↑ Edith Newhall (October 29, 2001). "Down to Earth". New York Magazine.

- ↑ Vincent Katz (September 1994). "James Croak Stux Gallery". Artnews.

- ↑ Leslie Wolf (November 18, 1983). "Review". LA Weekly.

- ↑ Catherine Dorsey (December 15, 1998). "The Dirty Business of Art". Port Folio Weekly.

- ↑ "The Dig". Salon.com. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Biography". Edge.org. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "List of Contributors". Edge.org. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Supra note 20

- ↑ "A Show of Hands". New York Times. May 1999.

- ↑ "Artist Profile". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Carlos Suarez de Jesus (January 5, 2006). "The Large and the Small of It". New Times.

- ↑ Colin Gardner (November 1983). "Revising the Archetype". Artweek.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dirt Sculpture Process". Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "James Croak". Retrieved 4 February 2012.