Ja'far al-Sadiq

| Ja'far al-Sadiq جعفر الصادق (Arabic) 6th Imam of Twelver and Mustaali Shiaa | |

|---|---|

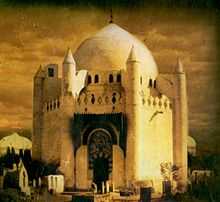

_and_other_Imams.JPG) His desecrated grave at Al-Baqi' in Saudi Arabia | |

| Born |

c. 23 April 702 CE[1] (17 Rabi' al-awwal 83 AH) Medina, Umayyad Empire |

| Died |

c. 7 December 765 (aged 63) (15 Shawwal 148 AH) Medina, Umayyad Empire |

Cause of death | Death by poisoning |

Resting place |

Jannatul Baqi, Saudi Arabia 24°28′1″N 39°36′50.21″E / 24.46694°N 39.6139472°E |

| Other names | Ja'far ibn Muhammad ibn Ali |

| Ethnicity | Arab (Quraysh) |

| Title | |

| Term | 733 – 765 CE |

| Predecessor | Muhammad al-Baqir |

| Successor | Musa al-Kadhim |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Unknown |

| Spouse(s) |

Fatima bint al-Hussain'l-Athram |

| Children |

List

|

| Parents |

Muhammad al-Baqir Farwah bint al-Qasim |

|

Notes a 5th Imam of Nizari Ismaili Shia | |

Jaʿfar ibn Muhammad al-Sādiq (Arabic: جعفر بن محمد الصادق) (702–765 C.E. or 17th Rabī‘ al-Awwal 83 AH – 15th Shawwāl 148 AH) was a descendant of Ali from his father's side and a descendant of Abu Bakr from his mother's side and was himself a prominent Muslim jurist. He is revered as an Imam by the adherents of Shi'a Islam and as a renowned Islamic scholar and personality by Sunni Muslims. The Shi'a Muslims consider him to be the sixth Imam or leader and spiritual successor to Muhammad.[5] The internal dispute over who was to succeed Ja'far as Imam led to schism within Shi'a Islam.[5] Al-Sadiq was celebrated among his brothers and peers and stood out among them for his great personal merits.[6] He is highly respected by both Sunni and Shi'a Muslims for his great Islamic scholarship, pious character, and academic contributions.

Shi'a Islamic fiqh, Ja'fari jurisprudence is named after him.The books on Ja'fari jurisprudence were later written by Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni (864- 941), Ibn Babawayh (923-991), and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201-1274).

As well as being considered an Imam of the Shi'a, he is revered by the Naqshbandi Sunni Sufi chain.[7]

He was a polymath: an astronomer, Imam, Islamic scholar, Islamic theologian, writer, philosopher, physician, physicist and scientist.[8] He is also reported to be the teacher of the famous chemist, Jābir ibn Hayyān (Geber).[9][10]

Birth and family life

Ja'far al-Sadiq was born in Madinah on 24 April 702 AD (17 Rabi' al-Awwal, 83 AH), to Muhammad al-Baqir (son of Zayn al-‘Ābdīn, son of Husayn son of Ali) and Umm Farwah (daughter of Al-Qasim son of Muhammad son of Abu Bakr).

Aishas brother Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr was the son of Abu Bakr raised by Ali.[11] When A'isha's brother Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr was killed by the Umayyad Empire,[11] she raised and taught her nephew Qasim ibn Muhammad ibn Abu Bakr. Qasim's mother was from Ali's family and Qasim's daughter Farwah bint al-Qasim was married to Muhammad al-Baqir and was the mother of Ja'far al-Sadiq. Therefore, Qasim was the grandson of Abu Bakr, the first Caliph, and the grandfather of Ja'far al-Sadiq. Ja'far's grandfather from his mothers side Qasim was raised and taught by A'isha, after his father was killed by the Umayyads.

Ja'far ibn Muhammad has three titles; they are as-Sadiq, al-Fadil, and at-Tahir.[2]

Ja'far al-Sadiq was 34 years old when his father was poisoned upon which, according to Shi'a tradition, he inherited the position of Imam.

Lineage

- Ja'far al-Sadiq s/o Muhammad al-Baqir s/o ‘Alī s/o Husayn s/o Ali (husband of Fatimah, the daughter of Prophet Muhammed) s/o Abu Talib

- Ja'far al-Sadiq s/o Muhammad al-Baqir s/o Fatimah d/o Hasan s/o Fatimah d/o Muhammad

- Ja'far al-Sadiq s/o Umm Farwah d/o Al-Qasim s/o Muhammad s/o Abu Bakr (biological father)

- Ja'far al-Sadiq s/o Umm Farwah d/o Al-Qasim s/o Muhammad s/o stepson and adopted son of Ali

Marriage and offspring

Ja'far married Fatima Al-Hasan, a descendant of Hasan ibn Ali, who gave him two sons Isma'il ibn Jafar (the Ismaili Imām-designate) and Abdullah al-Aftah.

Following his wife's death Al-Sadiq purchased a slave named Hamidah Khātūn (Arabic: حميدة خاتون), freed her, trained her as an Islamic scholar, and then married her. She bore Musa al-Kadhim (the seventh Imam) and Muhammad al-Dibaj and was revered by the Shī‘ah, especially by women, for her wisdom. She was known as Hamidah the Pure. Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq used to send women to learn the tenets of Islam from her, and used to remark about her, "Hamidah is pure from every impurity like the ingot of pure gold."[12]

Scholarly attainments

As a child, Ja'far Al-Sadiq studied under his grandfather, Zayn al-Abidin. After his grandfather's death, he studied under and accompanied his father, Muhammad al-Baqir, until Muhammad al-Baqir died in 733.

Ja'far Al-Sadiq became well versed in Islamic sciences, including Qur'an and Hadith. In addition to his knowledge of Islamic sciences, Ja'far Al-Sadiq was also an adept in natural sciences, mathematics, philosophy, astronomy, anatomy, alchemy and other subjects.

The foremost Islamic alchemist, Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan, known in Europe as Geber, was Ja'far Al-Sadiq's most prominent student. Ja'far Al-Sadiq was known for his liberal views on learning, and was keen to have discourse with Scholars of other views.

In the books actually written by these original jurists and scholars, there are very few theological and judicial differences between them. Imam Ahmad rejected the writing down and codifying of the religious rulings he gave. They knew that they might have fallen into error in some of their judgements and stated this clearly. They never introduced their rulings by saying, "Here, this judgement is the judgement of God and His prophet." [13] There is also very little text actually written down by Jafar al-Sadiq himself. They all give priority to the Qur'an and the Hadith (the practice of Muhammad). They felt that the Quran and the Hadith, the example of Muhammad provided people with almost everything they needed.

Ja'far Al-Sadiq is also cited in a wide range of historical sources, including al-Tabari, al-Yaqubi and Al-Masudi. Al-Dhahabi recognizes his contribution to Sunni tradition and Isma’ili scholars such as Qadi al-Nu'man[14] recorded his traditions in their work.[15]

- Scholars believed to have learned extensively from Ja'far Al-Sadiq:

- Jābir ibn Hayyān – known in Europe as Geber, a great alchemist.[16]

- Musa al-Kadhim – his son, the seventh Shi’ah Imam according to the Twelvers

- Isma'il ibn Jafar – his son, the sixth Ismaili Imam according to the Ismailis.

- Ali al-Uraidhi ibn Ja'far al-Sadiq- his youngest son.

- Mufadhal ibn Amr- his Gate keeper and a prominent student.

- Abū Ḥanīfa - founder of Hanafi school of thought.

- Malik ibn Anas – founder of the Maliki school of thought.

- Wasil ibn Ata – founder of the Mu'tazili school of thought.

Under the Umayyad rulers

Ja'far Al-Sadiq lived in violent times.[17] Ja'far Al-Sadiq was considered by many Shia (follower) of 'Ali ibn Abi Talib to be the sixth Shi'a imam, however, the Shi'ahs were considered heretics and rebels by the Umayyad caliphs. Many of Ja'far Al-Sadiq's relatives had died at the hands of the Umayyad.

After Hussein ibn Ali was betrayed, the people of Kufa called Zayd ibn Ali the grandson of Husayns over to Kufa. Zaydis believe that on the last hour of Zayd ibn Ali, Zayd ibn Ali was also betrayed by the people in Kufa who said to him: "May God have mercy on you! What do you have to say on the matter of Abu Bakr and Umar ibn al-Khattab?" Zayd ibn Ali said, "I have not heard anyone in my family renouncing them both nor saying anything but good about them...when they were entrusted with government they behaved justly with the people and acted according to the Qur'an and the Sunnah"[18][19][20][21]

Ja'far Al-Sadiq did not participate, but many of his kinsmen, including his uncle, were killed, and others were punished by the Umayyad caliph.[citation needed] There were other rebellions during these last years of the Umayyad, before the Abbasids succeeded in grasping the caliphate and establishing the Abbasid dynasty in 750 CE, when Ja'far Al-Sadiq was 48 years old.[citation needed]

Muhammad al-Baqir and his son, Jaffar al-Sadiq, explicitly rejected the idea of armed rebellion.[22] Many rebel factions tried to convince Ja'far al-Sadiq to support their claims. Ja'far Al-Sadiq evaded their requests without explicitly advancing his own claims. Al-Sadiq declared that even though he, as the designated imam, was the true leader of the ummah, he would not press his claim to the caliphate.[23] He is said to burned their letters (letters promising him the caliphate) commenting, "This man is not from me and cannot give me what is in the province of Allah". Ja'far Al-Sadiq's prudent silence on his true views is said to have established Taqiyya as a Shi'a doctrine. Taqiyya says that it is acceptable to hide one's true opinions if by revealing them, one put oneself or others in danger.[17]

Under the Abbasid rulers

The new Abbasid rulers, who had risen to power on the basis of their claim to descent from Muhammad's uncle ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib, were extremely suspicious of Ja'far al-Sadiq, whom many considered to have a better claim to the caliphate. Many followers of Zayd ibn Ali were ready to listen to al-Sadiq after being prosecuted ruthlessly by the Abbasids.[23] Al-Sadiq was watched closely and, occasionally, imprisoned to cut his ties with his followers.[17][23] Ja'far endured the persecution patiently and continued his study and writing wherever he found himself.

He died on 8 December 765. He was poisoned by Al-Mansur.[17] He is buried in Medina, in the famous Jannatul Baqee' cemetery.

Succession

After Ja'far al-Sadiq's death during the reign of the ‘Abbāsids, various Shī‘ī groups organised in secret opposition to their rule. Among them were the supporters of the proto-Ismā‘īlī community, of whom the most prominent group were called the "Mubārakiyyah".

There are hadīth which state that Ismā‘īl ibn Ja‘far "al-Mubārak"[citation needed] would be heir to the Imamate, as well as those that state Musa al-Kadhim[4][24] was to be the heir. However, Ismā‘īl predeceased his father.

Some of the Shī‘ah claimed Ismā‘īl had not died, but rather gone into hiding, but the proto-Ismā‘īlī group accepted his death and therefore that his eldest son, Muḥammad ibn Ismā‘īl, was now Imām. Muḥammad remained in contact with this "Mubārakiyyah" group, most of whom resided in Kūfah. [citation needed]

In contrast, Twelvers don't believe that Isma'il ibn Jafar was ever given the nass ("designation of the Imamate"),[25][26] but they acknowledge that this was the popular belief among the people at the time.[27] Both Shaykh Tusi[25] and Shaykh al-Sadūq[26] did not believe that the divine designation was changed (called Bada'), arguing that if matters as important as Imāmate were subject to change, then the fundamentals of belief should also be subject to change. Thus Twelvers accept that Mūsá al-Kāżim was the only son who was ever designated for Imāmate.

This is the initial point of divergence between the proto-Twelvers and the proto-Ismā‘īlī. This disagreement over the proper heir to Ja‘far has been a point of contention between the two groups ever since. The split among the Mubārakiyyah came with Muḥammad's death. The majority of the group denied his death; they recognised him as the Mahdi. The minority believed in his death and would eventually emerge in later times as the Fāṭimid Ismā‘īlī, ancestors to all modern groups.

Another Shia branch that emerged around the figure of Ja'far al-Sadiq was the Tawussite Shia. Following the death of al-Sadiq, the Tawussite's denied that he died and instead believed in his Mahdism.

Another Shia branch claimed that al-Sadiq's eldest surviving son Abdullah al-Aftah was the Imam to succeed his father. This branch was known as the Fathites. There is little evidence of them surviving beyond al-Aftah’s death, since he is commonly believed to have left no descendants.[28]

Timeline

| Clan of the Quraysh Born: 17 Rabī‘ al-Awwal 83 AH ≈ 24 April 702 CE Died: 15th Shawwāl 148 AH ≈ 8 December 765 CE | ||

| Shia Islam titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Muhammad al-Baqir |

6th Imam of Shia Islam 743–765 |

Succeeded by Musa al-Kadhim Twelver successor |

| Succeeded by Isma'il ibn Jafar Ismaili successor | ||

| Succeeded by Abdullah al-Aftah Fathite successor | ||

See also

- Husayn ibn Ali

- Ali al-Rida

- Muhammad al-Taqi

- Ali al-Hadi

- Hasan al-Askari

- Muhammad al-Mahdi

- Al-Abbas ibn Ali

- Qasim ibn Hasan

- Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah

- Aban ibn abi-Ayyash

- Waqifite Shia

References

- ↑ Shabbar, S.M.R. (1997). Story of the Holy Ka’aba. Muhammadi Trust of Great Britain. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 A Brief History of The Fourteen Infallibles. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. 2004. p. 123. ISBN 964-438-127-0.

- ↑ A Brief History of The Fourteen Infallibles. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. 2004. p. 131. ISBN 964-438-127-0.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Shaykh al-Mufid. "The Infallibles – Taken from Kitab al Irshad". Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Ja'far ibn Muhammad." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Sheikh al Mufid. Kitab al-Irshad. pp. 408–430.

- ↑

- ↑ "Debates of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq (A.S.)". Alhassanain.com. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ↑ Glick, Thomas; Eds (2005). Medieval science, technology, and medicine : an encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. p. 279. ISBN 0-415-96930-1.

- ↑ Haq, Syed N. (1994). Names, Natures and Things. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Volume 158/ Kluwar Academic Publishers. pp. 14–20. ISBN 0-7923-3254-7.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Nahj al-Balagha, Sermon 71, Letter 27, Letter 34, Letter 35

- ↑ Akhtar Rizvi, Sayyid Sa'eed, Slavery From Islamic and Christian Perspectives. Vancouver Islamic Educational Foundation. ISBN 0-920675-07-7

- ↑ "Modernist Islam, 1840-1940: A Sourcebook By Charles Kurzman - Page 236". Books.google.co.uk. 2002-09-13. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ↑ Madelung, W., The Sources of Ismāīlī Law, The University of Chicago Press, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Jan., 1976), pp. 29-40

- ↑ Meri, Josef W. "Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia". Routledge, NY. 2005, p 409 ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0

- ↑ "Encyclopædia Iranica". Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Campo, Juan E. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam (Encyclopedia of World Religions). USA: Facts on File. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1.

- ↑ Islam re-defined: an intelligent man's guide towards understanding Islam - Page 54

- ↑ "Rebellion and Violence in Islamic Law By Khaled Abou El Fadl page 72". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ↑ The waning of the Umayyad caliphate by Tabarī, Carole Hillenbrand, 1989, p37, p38

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Religion Vol.16, Mircea Eliade, Charles J. Adams, Macmillan, 1987, p243. "They were called "Rafida by the followers of Zayd"

- ↑ Moezzi, M Ali Amir (1994). The Divine Guide in Early Shi'sm : The Sources of Esotericism in Islam (1st ed.). State University of New York Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7914-2122-2.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Armstrong, Karen (2000). Islam: A Short History. USA: Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-679-64040-0.

- ↑ an-Nu'mani, Ibn Abu Zaynab (2003). "24 – entire chapter". al-Ghayba Occultation. Ansariyan Publications.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 al-Tusi, Muhammad ibn al-Hasan (2003). Kitab al-ghaybah. Dar al-Kutub al-Islamiyah. p. 264.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 al-Qummi, Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Babawayh. al-Imamah wa al-Tabsirah min al-Hayrah. pp. 149–150.

- ↑ al-Tusi, Muhammad ibn al-Hasan (2003). Kitab al-ghaybah. Dar al-Kutub al-Islamiyah. pp. 56,121.

- ↑ Gleave, Robert. Scripturalist Islam: The History and Doctrines of the Akhbari Shia School, Brill, 2007, pp 18 ISBN 978-90-04-15728-6

Further reading

- Muhammed Al-Husain Al-Mudaffar, Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq.

- Sayyid Mahdi as-Sadr, THE AHLUL-BAYT Ethical Role-Models.

- Mohammad Hussein il Adeeb, The Brief History of the Fourteen Infallibales.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Ja'far al-Sadiq |

- "Encyclopædia Iranica". Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Ja'far ibn Muhammad, an article of Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Imam Ja'far as-Sadiq's life according to a Sunni Sufi source (Naqshbandiya Mujaddidiya Khalidiya Haqqaniya Tariqa of Sufism)

- Imam al-Sadiq by Shaykh Mohammed al-Husayn al-Muzaffar

- Tawheed al-Mufadhdhal – as dictated by Imam Ja'far as-Sadiq to Al-Mufadhdhal

- The Sixth Imam

- Biography of the Sixth Imam by Sheikh al-Mufid

- Kaukab Ali Mirza (First ed. 1996, Latest ed. 2012). The great muslim scientist and philosopher Imam Jafar Ibn Mohammed As-Sadiq (A.S.). Willowdale, Ont. ISBN 0969949014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- This book is a translation of "Maghze Mutafakkir Jehan Shia", the famous Persian book, which has been published four times in Tehran, Iran. The Persian book is itself a translation from a French thesis published by The Research Committee of Strasbourg, France, about the contribution made by Imam Ja'far as-Sadiq (A.S.) to science, philosophy, literature and irfan (gnosticism). 'Kaukab Ali Mirza' did the English translation from Persian

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||