Jacob Emden

Jacob Emden. also known as Ya'avetz (June 4, 1697, Altona – April 19, 1776, Altona), was a leading German rabbi and talmudist who championed Orthodox Judaism in the face of the growing influence of the Sabbatean movement. He was acclaimed in all circles for his extensive knowledge, thus Moses Mendelssohn, founder of the Jewish Enlightenment movement, wrote to him as "your disciple, who thirsts for your words."[1] Although Emden did not approve of the Hasidic movement which evolved during his lifetime, his books are highly regarded amongst the Hasidim.[1] Thirty-one works were published during his lifetime, ten posthumously while others remain in manuscript.[1]

Emden was the son of the Chacham Tzvi, and a descendant of Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm. He lived most his life in Altona (now a part of Hamburg, Germany), where he held no official rabbinic position and earned a living by printing books.[2] His son was Meshullam Solomon, rabbi of the Hamboro' Synagogue in London who claimed authority as Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom from 1765 to 1780.[3]

Biography

Until seventeen, Emden studied Talmud under his father Tzvi Ashkenazi, a foremost rabbinic authority, first at Altona, then at Amsterdam (1710–1714). In 1715 Emden married Rachel, daughter of Mordecai ben Naphtali Kohen, rabbi of Ungarisch-Brod, Moravia, and continued his studies in his father-in-law's yeshivah.[4] Emden became well versed in all branches of Talmudic literature; later he studied philosophy, kabbalah, and grammar, and made an effort to acquire the Latin and Dutch languages, in which, however, he was seriously hindered by his belief that a Jew should occupy himself with secular sciences only during the hour of twilight.[4] He was opposed to philosophy and maintained that the views contained in The Guide to the Perplexed could not have been authored by Maimonides, but rather by an unknown heretic.[2]

Emden spent three years at Ungarisch-Brod, where he held the office of private lecturer in Talmud. Later he became a dealer in jewelry and other articles, an occupation which compelled him to travel.[4] He generally declined to accept the office of rabbi, though in 1728 he was induced to accept the rabbinate of Emden, from which place he took his name.[4]

In 1733 Emden returned to Altona, where he obtained the permission of the Jewish community to possess a private synagogue. Emden was at first on friendly terms with Moses Hagis, the head of the Portuguese-Jewish community at Altona, who was afterward turned against Emden by some calumny. His relations with Ezekiel Katzenellenbogen, the chief rabbi of the German community, were strained from the very beginning. Emden seems to have considered every successor of his father as an intruder.[4]

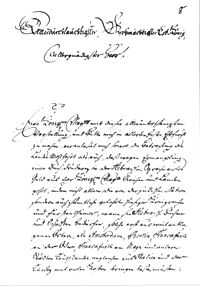

A few years later Emden obtained from the King of Denmark the privilege of establishing at Altona a printing-press. He was soon attacked for his publication of the siddur (prayer book) Ammudei Shamayim, being accused of having dealt arbitrarily with the text. His opponents did not cease denouncing him even after he had obtained for his work the approbation of the chief rabbi of the German communities.[4]

Sabbatean controversy

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kabbalah | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Concepts

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

History

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Practices |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

People

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Role

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Emden accused Jonathan Eybeschutz of being a secret Sabbatean. The controversy lasted several years, continuing even after Eybeschütz's death. Emden's assertion of Eybeschütz's heresy was chiefly based on the interpretation of some amulets prepared by Eybeschütz, in which Emden saw Sabbatean allusions. Hostilities began before Eybeschütz left Prague, and in 1751, when Eybeschütz was named chief rabbi of the three communities of Altona, Hamburg, and Wansbeck, the controversy reached the stage of intense and bitter antagonism. Emden maintained that he was at first prevented by threats from publishing anything against Eybeschütz. He solemnly declared in his synagogue the writer of the amulets to be a Sabbatean heretic and deserving of excommunication. In Megillat Sefer, he even accuses Eybeschütz of having an incestuous relationship with his own daughter, and of fathering a child with her.

The majority of the community, including R. Aryeh Leib Halevi-Epstein of Konigsberg, favored Eybeschütz; thus the council condemned Emden as a slanderer. People were ordered, under pain of excommunication, not to attend Emden's synagogue, and he himself was forbidden to issue anything from his press. As Emden still continued his philippics against Eybeschütz, he was ordered by the council of the three communities to leave Altona. This he refused to do, relying on the strength of the king's charter, and he was, as he maintained, relentlessly persecuted. His life seeming to be in actual danger, in May 1751 he left the town and took refuge in Amsterdam, where he had many friends and where he joined the household of his brother-in-law, Aryeh Löb b. Saul, rabbi of the Ashkenazic community.

Emden's cause was subsequently taken up by the court of Frederick V of Denmark, and on June 3, 1752, a judgment was given in favor of Emden, severely censuring the council of the three communities and condemning them to a fine of one hundred thalers. Emden then returned to Altona and took possession of his synagogue and printing-establishment, though he was forbidden to continue his agitation against Eybeschütz. The latter's partisans, however, did not desist from their warfare against Emden. They accused him before the authorities of continuing to publish denunciations against his opponent. One Friday evening (July 8, 1755) his house was broken into and his papers seized and turned over to the "Ober-Präsident," Von Kwalen. Six months later Von Kwalen appointed a commission of three scholars, who, after a close examination, found nothing, which could incriminate Emden.

The truth or falsity of his denunciations against Eybeschütz cannot be proved; Gershom Scholem wrote much on this subject, and his student Perlmutter devoted a book to proving it. According to historian David Sorkin, Eybeschütz was probably a Sabbatean,[5] and Eybeschütz's son openly declared himself to be a Sabbatean after his father's death.

Other notable events

In 1756 the members of the Synod of Constantinov applied to Emden to aid in repressing the Sabbatean movement. As the Sabbatean referred much to the Zohar, Emden thought it wise to examine that book, and after a careful study he concluded that a great part of the Zohar was the production of an impostor.[6]

Emden's works show him to have been possessed of critical powers rarely found among his contemporaries. He was strictly Orthodox, never deviating the least from tradition, even when the difference in time and circumstance might have warranted a deviation from custom. Emden's opinions were often viewed as extremely unconventional from the perspective of strictly traditional mainstream Judaism, though not so unusual in more free-thinking Enlightenment circles. Emden had friendly relations with Moses Mendelssohn, founder of the Haskalah movement, and with a number of Christian scholars.[7]

In 1772 the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, having issued a decree forbidding burial on the day of death, the Jews in his territories approached Emden with the request that he demonstrate from the Talmud that a longer exposure of a corpse would be against the Law. Emden referred them to Mendelssohn, who had great influence with Christian authorities; but as Mendelssohn agreed with the ducal order, Emden wrote to him and urged the desirability of opposing the duke if only to remove the suspicion of irreligiousness he (Mendelssohn) had aroused by his associations.

Views on the spread of monotheism

Emden was a traditionalist who responded to the ideals of tolerance being circulated during the 18th-century Enlightenment. He stretched the traditional inclusivist position into universal directions.[8] Believing, like Maimonides, that Christianity and Islam have important roles to play in God's plan for mankind, he wrote:

We should consider Christians and Moslems as instruments for the fulfilment of the prophecy that the knowledge of God will one day spread throughout the earth. Whereas the nations before them worshipped idols, denied God's existence, and thus did not recognize God's power or retribution, the rise of Christianity and Islam served to spread among the nations, to the furthest ends of the earth, the knowledge that there is One God who rules the world, who rewards and punishes and reveals Himself to man.

In a remarkable apology for Christianity, he wrote that that the original intention of Jesus, and especially of Paul, was to convert only the Gentiles to the Seven Laws of Noah and to let the Jews follow the Mosaic law.[9] Emden praised the ethical teachings of the founder of Christianity, considering them as being beneficial to the Gentiles by removing the prevalence of idolatry and bestowing upon them a "moral doctrine."[1][10] Emden also suggested that ascetic Christian practices provided additional rectification of the soul in the same way that Judaic commandments do.[1]

Stance on polygamy and concubines

In his responsum, Emden theoretically advocated the taking of a pilegesh (concubine) by a scholar since the Rabbis stated that "the greater the man, the greater his evil inclination." He collected many Talmudic and medieval examples from Judaic literature that support such behavior.[11] Although he never put his theories into practice, he criticised the institute of obligatory matrimony and suggested that it's permissible for a Jew to cohabit freely with a single Jewish woman or even with several women without marriage, or as an addition to the legal wife. He wished to revoke the ban on polygamy instituted by Rabbeinu Gershom as he believed it erroneously followed Christian morals, but admitted he did not have the power to do so.[2]

Published works

- 'Edut be-Ya'aḳov, on the supposed heresy of Eybeschütz, and including Iggeret Shum, a letter to the rabbis of the "Four Lands." Altona, 1756.

- Shimmush, comprising three smaller works: Shoṭ la-Sus and Meteg la-Hamor, on the growing influence of the Shabbethaians, and Sheveṭ le-Gev Kesilim, a refutation of heretical demonstrations. Amsterdam, 1758-62.

- Shevirat Luḥot ha-Aven, a refutation of Eybeschütz's "Luḥot 'Edut." Altona, 1759.

- Seḥoḳ ha-Kesil, Yeḳev Ze'ev, and Gat Derukah, three polemical works published in the "Hit'abbeḳut" of one of his pupils. Altona, 1762.

- Miṭpaḥat Sefarim, in two parts: the first part showing that part of the Zohar is not authentic but a later compilation; the second, a criticism on "Emunat Ḥakamim" and "Mishnat Ḥakamim," and other seforim and polemical letters addressed to the rabbi of Königsberg. Altona, 1761-68.

- Ḥerev Pifiyyot, Iggeret Purim, Teshubot ha-Minim, and Zikkaron be-Sefer, on money-changers and bankers (unpublished).

- Leḥem Shamayim, a commentary on the Mishnah, with a treatise in two parts, on Maimonides' "Yad," Bet ha-Beḥirah. Altona, 1728; Wandsbeck, 1733.

- Iggeret Biḳḳoret, responsa. Altona, 1733.

- She'elat Ya'abeẓ, a collection of 372 responsa. Altona, 1739-59.

- Siddur Tefillah, an edition of the ritual with a commentary, grammatical notes, ritual laws, and various treatises, in three parts: Bet-El, Sha'ar ha-Shamayim, and Migdal 'Oz. It also includes a treatise entitled Eben Boḥan, and a criticism on Menahem Lonzano's "'Avodat Miḳdash," entitled Seder Abodah. Altona, 1745-48.

- 'Eẓ Avot, a commentary to Avot, with Leḥem Neḳudim, grammatical notes. Amsterdam, 1751.

- Sha'agat Aryeh, a sermon, also included in his Ḳishshurim le-Ya'aḳov. Amsterdam, 1755.

- Seder 'Olam Rabbah ve-Zuṭa, the two Seder 'Olam and the Megillat Ta'anit, edited with critical notes. Hamburg, 1757.

- Mor u-Ḳeẓi'ah, novellæ on the Oraḥ. Ḥayyim (the novellæ on the Yoreh De'ah, Even ha'Ezer, and Hoshen Mishpat of Mor u-Ḳeẓi'ah - unpublished)

- Ẓiẓim u-Feraḥim, a collection of kabalistic articles arranged in alphabetical order. Altona, 1768.

- Luaḥ Eresh, grammatical notes on the prayers, and a criticism of Solomon Hena's "Sha'are Tefillah." Altona, 1769.

- Shemesh Ẓedaḳah. Altona, 1772.

- Pesaḥ Gadol, Tefillat Yesharim, and Ḥoli Ketem. Altona, 1775.

- Sha'are 'Azarah. Altona, 1776.

- Divre Emet u-Mishpaṭ Shalom (n. d. and n. p.).

- Megillat Sefer, containing biographies of himself and of his father. Warsaw 1897

- Kishshurim le Ya'akob, collection of sermons.

- Marginal novellæ on the Babylonian Talmud.

His unpublished rabbinical writings are the following:

- Ẓa'aḳat Damim, refutation of the blood accusation in Poland.

- Halakah Pesuḳah.

- Hilketa li-Meshiḥa, responsum to R. Israel Lipschütz.

- Mada'ah Rabbah.

- Gal-'Ed, commentary to Rashi and to the Targum of the Pentateuch.

- Em la-Binah, commentary to the whole Bible.

- Em la-Miḳra we la-Masoret, also a commentary to the Bible.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Falk, Harvey. Journal of ecumenical studies Volume 19, no. 1 (Winter 1982), Rabbi Jacob Emden's Views on Christianity, pp. 105–11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Louis Jacobs (1995). The Jewish religion: a companion. Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-826463-7. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Jacob Emden (4 May 2011). Megilat Sefer: The Autobiography of Rabbi Jacob Emden (1697-1776). PublishYourSefer.com. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-61259-001-1. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Solomon Schechter, M. Seligsohn. Emden, Jacob Israel ben Zebi, Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

- ↑ David Sorkin, The Transformation of German Jewry, 1780-1840, Wayne State University Press, 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Taken from the Public Domain Jewish Encyclopedia article

- ↑ The Jewish enlightenment, by Shmuel Feiner, ch. 1, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003

- ↑ Rabbi Dr. Alan Brill. Judaism and Other Religions: An Orthodox perspective, Commissioned by the World Jewish Congress for the World Symposium of Catholic Cardinals and Jewish Leaders (January 2004).

- ↑ Emil G. Hirsch, Judah David Eisenstein. Gentile, Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

- ↑ Sandra B. Lubarsky (November 1990). Tolerance and transformation: Jewish approaches to religious pluralism. Hebrew Union College Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-87820-504-2. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ See: Translation of Jacob Emden’s responsa on pilegesh

External links

- Emden, Jacob Israel Ben Zebi Ashkenazi, jewishencyclopedia.com

- Jacob Emden, jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- Rabbi Jacob Emden's View on Christianity and the Noachite Commandments, Reprinted from the Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 19:1, Winter 1982

- Responsum of Jacob Emden on the Polygamy Ban and the Pilegesh, from Shelyot Ye'avetz, v 2, 15

- Cohen, Mortimer J. (1948), "Was Eibeschuetz a Sabbatian?", The Jewish Quarterly Review, XXXIX (1): 51–62.

- Cohen, Mortimer Joseph, Jacob Emden, A Man of Controversy, Philadelphia, Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1937.

- Schacter, Jacob J., Rabbi Jacob Emden: Life and Major Works, Diss., Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1988.

|