Ishar Singh (poet)

Ishar Singh ‘Ishar’ (1892–1966) was one of the most renowned Punjabi humorous poets of the 20th century.

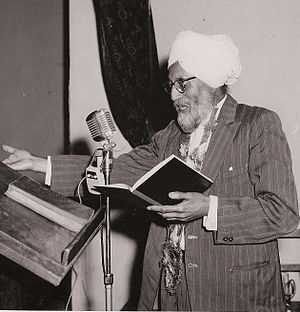

His poems centred around his comic creation ‘Bhaiya’, who was used as a vehicle for biting satirical comment on all aspects of Indian society and culture. Ishar Singh’s compositions were delivered in his native language – the particular form of Punjabi spoken in the Potwar region, which is now part of Pakistan. A tall, bespectacled Sikh, he published at least 12 poetic collections involving Bhaiya. But he lived in a time and place where culture was primarily transmitted by oral means, and where poetry was one of the chief forms of public entertainment. So it was in the mass public recitals – or ‘kavi darbars’ – that his works were most keenly and widely appreciated.

Early life and career

Ishar Singh was born on 12 December 1892 in Kaneti, near Rawalpindi, in the Potwar plateau of the Punjab. The area was then part of British India, but is now in Pakistan.

He was the younger of two sons of Dhera Singh 'Shah', a wealthy money lender. But he showed no interest in money himself, instead displaying a prodigious early aptitude for poetry while studying at Sukho Khalsa High School. He was aged just 13 when his first poetic collection, Naurangiya Alum, was published locally by his headmaster.[1] At 16 he moved to study at the prestigious Khalsa College in Amritsar, where he recited his religious poems every week in the gurdwaras of Sikhism's holiest city.

He was married at 17 and moved to Karachi three years later to take his first job, a clerical role in the Post Office. This marked the beginning of a long career in the service, which he would combine with his ever burgeoning literary success.

From Karachi he transferred to Lahore, considered the hub of Punjabi poetry, before moving on to work as a postmaster in his home district of Rawalpindi.[2]

All the while he wrote poetry in his spare time, publishing his works in local journals and reading them out at public functions. These earlier compositions were serious in tone, usually on religious matters. He also composed romantic and melancholic works, which he was to later look back on with embarrassment.[3]

It was not until 1928 that he finally realised his true talent – which was to make people laugh. It was in that year that he entered a competition held by Charan Singh Shahid, editor of the weekly satirical journal Mauji, inviting humorous poems on the subject of Fashiondaar Vauti (Fashionable Wife). Ishar Singh beat 69 other entrants - many of greater fame - to the first prize of two sovereigns.[4] The award marked a turning point in his life, highlighting fresh possibilities beyond the Post Office, and from then onwards his poems always looked to the lighter side of life.

Poems

Although intended to create laughter, Ishar Singh’s compositions were not simply a form of idle and frivolous entertainment. Rather, they were intended as a satire on common social, cultural and religious values.

Ishar Singh used his piercing wit to puncture the pomposity of the rich and powerful, and to expose popular prejudices and injustices, many of which had been entrenched in the Indian psyche for centuries.

His acute observations touched on every aspect of life, from the minutiae of family relationships to matters of grand theology. No subject was taboo for him, and many of his pronouncements might be considered too close to the bone in today’s more politically correct age.

His creation ‘Bhaiya’ was the medium through which Ishar Singh attacked the various hypocrisies, superstitions and other absurdities he observed around him. Bhaiya was used in various guises - sometimes as himself, sometimes as his father or any other character - depending on the subject matter.

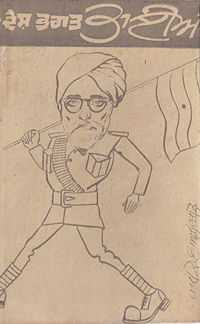

In total, Ishar Singh is thought to have composed over 2,500 poems, of which several hundred featured in 12 published collections: Bhaiya; Rangila Bhaiya; Nirala Bhaiya; Nava Bhaiya; Gurmukh Bhaiya; Bhaiya Tilak Piya; Bhaiya Vaid Rogian Da; Premi Bhaiya; Desh Bhagat Bhaiya; Mastana Bhaiya; Hansmukh Bhaiya and Oncemore Bhaiya.

Although many of the poems in these books were written years, or even decades, earlier, most were not published until the last few years of his life. Indeed, it was only after retiring from the Post office in 1954 that Ishar Singh attained truly widespread fame.

As late as 1955, when he had already published five books, he complained that his works were being denied a proper audience. He described how he had even been forcefully quietened in gurdwaras for reciting poems that were considered inappropriate in a holy setting.[5]

But it was in the same year that he made his ultimate breakthrough, when his poem Mera Marna (My Death) gained an audience on All India Radio. It caused an overnight sensation, and was quickly followed by Mera Jamna (My Birth).[6]

In the later years of his life, tens of thousands of people would turn up to his performances at kavi darbars, where he was usually the final - and most popular - act on the stage. He was in huge demand to speak at weddings and parties, but would never charge for his appearances. He had no need to, as audience members showered him with money and other gifts.

One of his chief patrons was the Maharajah of Patiala Yadavindra Singh, but his poems were appreciated by a wide strata of society, and he was always at pains to retain the common touch. For although he was a well-read man whose poems displayed his full learning and erudition, they were always written in the earthy language of the Punjab.

But while the language was often plain and somewhat rustic, there was a keen art behind the poetry, which employed carefully structured meter and rhyme. Many of his poems were delivered in rhyming couplets, while others used varying combinations of rhyming lines.

It was through this mix of tight rhythmic structure, straightforward humour and - above all - fearless commentary, that Ishar Singh was eventually acknowledged in the field of Punjabi poetry as the 'Has Ras de Badshah' (King of Humour).

He was handed this title by the Chief Minister of the Punjab, Pratap Singh Kairon, when he first read out Mera Marna on All India Radio.[6] But it was a reputation he truly earned among his rivals after they set him the daunting challenge of turning his poetic wit to the most sombre event in Sikh history – the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur. In 1675, the religion's ninth founding Guru was publicly executed in the main thoroughfare in Delhi – at the behest of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb - for refusing to convert to Islam.

On the anniversary of the martyrdom nearly 300 years later, Ishar Singh rose to the challenge, and delivered his poem to a serious-minded audience in a Delhi maidan. Moments later, the audience was reportedly rolling around in amusement.[7] In a delicate balancing act of tone and judgement, Ishar Singh lampooned the brutal and bloody intolerance of the Islamic rulers, while venerating the sanctity of the Guru’s ultimate sacrifice. Many observers considered this his finest work.

Further background

Although his family name was Chandhoke, he employed the common poetic construction of using his first name as a suffixed pen name. Thus he was known as Ishar Singh ‘Ishar’. In practice, however, he came to be so closely identified with his best known comic creation that the name ‘Bhaiya’ was usually tagged to the end of his full title.

He was married to Sita Wanti (died 1975), and had five sons and three daughters, who were all born in the Rawalpindi district.

In 1946, a year before the Partition of India created Muslim Pakistan, the entire family – by this time including grandchildren – moved over to live in Delhi, which would soon become capital of the new Hindu-majority India.

Ishar Singh transferred to the Post Office in Shimla in 1949, before retiring back to Delhi in 1954. He was to spend the rest of his days in the city, where he died of a heart attack on 15 January 1966, at the age of 73. The circumstances of his death were almost identical to those he described years earlier in Mera Marna.

As a man, he paid little respect to the standing and reputation of others. He would keep ministers of state waiting if he felt too tired to see them at social gatherings, while he was known to ridicule the hosts of the very events he was speaking at.

Even those who knew him best said it was difficult to get too close, as he was so entirely absorbed in his writings. His relatives recall how on one occasion, while staying with his son in Kenya in 1959, he journeyed to a park to work on his poetry. He removed his turban, jacket and shoes, and placed them beside him on a bench, before immersing himself in his notebook. It was only when he stopped writing, several hours later, that he noticed his clothing had been stolen. And when his son subsequently took him to report the theft at the police station, Ishar Singh could not even recall the colour of his own turban, jacket and shoes - such had been his dedication to his art that morning.[8]

Several of his descendants became well known in their own right. His eldest son, Hardit Singh (1919–1993), set up the successful Delhi-based firm Ditz Electricals, which still manufactures and supplies household appliances around India to this day.

Ishar Singh's second son, Narinjan Singh ‘Narinjan’ (1921–1991), was the only one of his children to carry on the family poetic tradition. Narinjan Singh regularly recited his own compositions - as well as those of his father - at social gatherings and kavi darbars, first in Delhi, then in Nairobi where he later moved, and finally, towards the end of his life, when he lived in Derby in the UK.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ishar Singh (poet). |

- ↑ From "Kuch Apne Walon" (01/07/1955), p.95 in Bhaiya Ishar Singh Ishar di Kavita(1992), ISBN 81-7116-136-7

- ↑ Oral recollection by his only surviving son, Hardev Singh (July 2008)

- ↑ From "Kuch Apne Walon", p.96 in Bhaiya Ishar Singh Ishar di Kavita

- ↑ p.96, ibid

- ↑ pp.96-97, ibid

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Oral recollection by Hardev Singh

- ↑ Oral recollection by his grandson Daljit Singh (July 2008)

- ↑ Oral recollection by his grandson Kultaran Singh (July 2008)

|