Ionization energy

The ionization energy (IE) of an atom or molecule describes the minimum amount of energy required to remove an electron (to infinity) from the atom or molecule in the gaseous state.[1]

- X + energy → X+ + e-

The term ionization potential has been used in the past but is not recommended.[2]

The units for ionization energy vary from discipline to discipline. In physics, the ionization energy is typically specified in electron volts (eV) and refers to the energy required to remove a single electron from a single atom or molecule. In chemistry, the ionization energy is typically specified as a molar quantity (molar ionization energy or enthalpy) and is reported in units of kJ/mol or kcal/mol (the amount of energy it takes for all the atoms in a mole to lose one electron each[3]).

The nth ionization energy refers to the amount of energy required to remove an electron from the species with a charge of (n-1). For example, the first three ionization energies are defined as follows:

- 1st ionization energy

- X → X+ + e-

- 1st ionization energy

- 2nd ionization energy

- X+ → X2+ + e-

- 2nd ionization energy

- 3rd ionization energy

- X2+ → X3+ + e-

- 3rd ionization energy

Values and trends

Generally the (n+1)th ionization energy is larger than the nth ionization energy. Always, the next ionization energy involves removing an electron from an orbital closer to the nucleus. Electrons in the closer orbitals experience greater forces of electrostatic attraction; thus, their removal requires increasingly more energy. Ionization energy becomes greater up and to the right of the periodic table.

Some values for elements of the third period are given in the following table:

| Element | First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Sixth | Seventh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | 496 | 4,560 | |||||

| Mg | 738 | 1,450 | 7,730 | ||||

| Al | 577 | 1,816 | 2,881 | 11,600 | |||

| Si | 786 | 1,577 | 3,228 | 4,354 | 16,100 | ||

| P | 1,060 | 1,890 | 2,905 | 4,950 | 6,270 | 21,200 | |

| S | 999.6 | 2,260 | 3,375 | 4,565 | 6,950 | 8,490 | 27,107 |

| Cl | 1,256 | 2,295 | 3,850 | 5,160 | 6,560 | 9,360 | 11,000 |

| Ar | 1,520 | 2,665 | 3,945 | 5,770 | 7,230 | 8,780 | 12,000 |

Large jumps in the successive molar ionization energies occur when passing noble gas configurations. For example, as can be seen in the table above, the first two molar ionization energies of magnesium (stripping the two 3s electrons from a magnesium atom) are much smaller than the third, which requires stripping off a 2p electron from the very stable neon configuration of Mg2+.

Ionization energy is also a periodic trend within the periodic table organization. Moving left to right within a period or upward within a group, the first ionization energy generally increases with a few discrepancies (aluminum and sulphur). As the nuclear charge of the nucleus increases across the period, the atomic radius decreases and the electron cloud becomes closer towards the nucleus.

Ionization energy increases from left to right in a period and decreases from top to bottom in a group.

Electrostatic explanation

Atomic ionization energy can be predicted by an analysis using electrostatic potential and the Bohr model of the atom, as follows (note that the derivation uses Gaussian units).

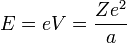

Consider an electron of charge -e and an atomic nucleus with charge +Ze, where Z is the number of protons in the nucleus. According to the Bohr model, if the electron were to approach and bind with the atom, it would come to rest at a certain radius a. The electrostatic potential V at distance a from the ionic nucleus, referenced to a point infinitely far away, is:

Since the electron is negatively charged, it is drawn inwards by this positive electrostatic potential. The energy required for the electron to "climb out" and leave the atom is:

This analysis is incomplete, as it leaves the distance a as an unknown variable. It can be made more rigorous by assigning to each electron of every chemical element a characteristic distance, chosen so that this relation agrees with experimental data.

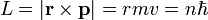

It is possible to expand this model considerably by taking a semi-classical approach, in which momentum is quantized. This approach works very well for the hydrogen atom, which only has one electron. The magnitude of the angular momentum for a circular orbit is:

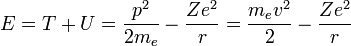

The total energy of the atom is the sum of the kinetic and potential energies, that is:

Velocity can be eliminated from the kinetic energy term by setting the Coulomb attraction equal to the centripetal force, giving:

Solving the angular momentum for v and substituting this into the expression for kinetic energy, we have:

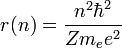

This establishes the dependence of the radius on n. That is:

Now the energy can be found in terms of Z, e, and r. Using the new value for the kinetic energy in the total energy equation above, it is found that:

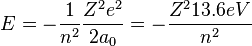

At its smallest value, n is equal to 1 and r is the Bohr radius a0 which equals to  . Now, the equation for the energy can be established in terms of the Bohr radius. Doing so gives the result:

. Now, the equation for the energy can be established in terms of the Bohr radius. Doing so gives the result:

Quantum-mechanical explanation

According to the more complete theory of quantum mechanics, the location of an electron is best described as a probability distribution. The energy can be calculated by integrating over this cloud. The cloud's underlying mathematical representation is the wavefunction which is built from Slater determinants consisting of molecular spin orbitals. These are related by Pauli's exclusion principle to the antisymmetrized products of the atomic or molecular orbitals.

In general, calculating the nth ionization energy requires calculating the energies of  and

and  electron systems. Calculating these energies exactly is not possible except for the simplest systems (i.e. hydrogen), primarily because of difficulties in integrating the electron correlation terms. Therefore, approximation methods are routinely employed, with different methods varying in complexity (computational time) and in accuracy compared to empirical data. This has become a well-studied problem and is routinely done in computational chemistry. At the lowest level of approximation, the ionization energy is provided by Koopmans' theorem.

electron systems. Calculating these energies exactly is not possible except for the simplest systems (i.e. hydrogen), primarily because of difficulties in integrating the electron correlation terms. Therefore, approximation methods are routinely employed, with different methods varying in complexity (computational time) and in accuracy compared to empirical data. This has become a well-studied problem and is routinely done in computational chemistry. At the lowest level of approximation, the ionization energy is provided by Koopmans' theorem.

Vertical and adiabatic ionization energy in molecules

Ionization of molecules often leads to changes in molecular geometry, and two types of (first) ionization energy are defined – adiabatic and vertical.[4]

Adiabatic ionization energy: The adiabatic ionization energy of a molecule is the minimum amount of energy required to remove an electron from a neutral molecule, i.e. the difference between the energy of the vibrational ground state of the neutral species and that of the positive ion. The specific equilibrium geometry of each species does not affect this value.

Vertical ionization energy: Due to the possible changes in molecular geometry that may result from ionization, additional transitions may exist between the vibrational ground state of the neutral species and vibrational excited states of the positive ion. In other words, ionization is accompanied by vibrational excitation. The intensity of such transitions are explained by the Franck–Condon principle, which predicts that the most probable and intense transition corresponds to the vibrational excited state of the positive ion that has the same geometry as the neutral molecule. This transition is referred to as the "vertical" ionization energy since it is represented by a completely vertical line on a potential energy diagram (see Figure).

For a diatomic molecule, the geometry is defined by the length of a single bond. The removal of an electron from a bonding molecular orbital weakens the bond and increases the bond length. In Figure 1, the lower potential energy curve is for the neutral molecule and the upper surface is for the positive ion. Both curves plot the potential energy as a function of bond length. The horizontal lines correspond to vibrational levels with their associated vibrational wave functions. Since the ion has a weaker bond, it will have a longer bond length. This effect is represented by shifting the minimum of the potential energy curve to the right of the neutral species. The adiabatic ionization is the diagonal transition to the vibrational ground state of the ion. Vertical ionization involves vibrational excitation of the ionic state and therefore requires greater energy.

In many circumstances, the adiabatic ionization energy is often a more desirable physical quantity since it describes the difference in energy between the two potential energy surfaces. However, due to experimental limitations, the adiabatic ionization energy is often difficult to determine, whereas the vertical detachment energy is easily identifiable and measurable.

Analogs of Ionization Energy to Other Systems

While the term ionization energy is largely used only for gas-phase atomic or molecular species, there are a number of analogous quantities that consider the amount of energy required to remove an electron from other physical systems.

Electron binding energy: A generic term for the ionization energy that can be used for species with any charge state. For example, the electron binding energy for the chloride ion is the minimum amount of energy required to remove an electron from the chlorine atom when it has a charge of -1. In this particular example, the electron binding energy has the same magnitude as the electron affinity for the neutral chlorine atom. In another example, the electron binding energy refers the minimum amount of energy required to remove an electron from the dicarboxylate dianion -O2C(CH2)8CO2-.

Work function: The minimum amount of energy required to remove an electron from a solid surface.

See also

- Electron affinity — a closely related concept describing the energy released by adding an electron to a neutral atom or molecule.

- Work function is the energy required to strip an electron from a solid to just outside its surface.

- Electronegativity is a number that shares some similarities with ionization energy.

- Koopmans' theorem, regarding the predicted ionization energies in Hartree–Fock theory.

- Di-tungsten tetra(hpp) has the lowest recorded ionization energy for a stable chemical compound.

References

- ↑ http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Ionization_potential.html

- ↑ Muller, P. (1994). "Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994)". Pure and Applied Chemistry 66 (5): 1077–1184. doi:10.1351/pac199466051077. ISSN 0033-4545.

- ↑ http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Inorganic_Chemistry/Descriptive_Chemistry/Periodic_Table_of_the_Elements/Ionization_Energy

- ↑ The difference between a vertical ionization energy and adiabatic ionization energy.