Involute

In the differential geometry of curves, an involute (also known as evolvent) is a curve obtained from another given curve by attaching an imaginary taut string to the given curve and tracing its free end as it is wound onto that given curve; or in reverse, unwound. It is a roulette wherein the rolling curve is a straight line containing the generating point. For example, an involute approximates the path followed by a tetherball as the connecting tether is wound around the center pole. If the center pole has a circular cross-section, then the curve is an involute of a circle.

Alternatively, another way to construct the involute of a curve is to replace the taut string by a line segment that is tangent to the curve on one end, while the other end traces out the involute. The length of the line segment is changed by an amount equal to the arc length traversed by the tangent point as it moves along the curve.

The evolute of an involute is the original curve, less portions of zero or undefined curvature. Compare Media:Evolute2.gif and Media:Involute.gif

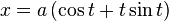

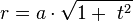

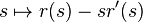

If the function  is a natural parametrization of the curve (i.e.,

is a natural parametrization of the curve (i.e.,  for all s), then :

for all s), then : parametrizes the involute.

parametrizes the involute.

The notions of the involute and evolute of a curve were introduced by Christiaan Huygens in his work titled Horologium oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum ad horologia aptato demonstrationes geometricae (1673).[1]

Parametric curve

Equations of an involute curve for a parametrically defined function ( x(t), y(t) ) are:

![X[x,y]=x-{\frac {x'}{{\sqrt {x'^{2}+y'^{2}}}}}\int _{a}^{t}{\sqrt {x'^{2}+y'^{2}}}\operatorname {d}t](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/e/b/a/5eba651d48ccddb1a178b73a41e1bc7c.png)

![Y[x,y]=y-{\frac {y'}{{\sqrt {x'^{2}+y'^{2}}}}}\int _{a}^{t}{\sqrt {x'^{2}+y'^{2}}}\operatorname {d}t](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/0/b/5/20b594516a4d9d3293f3341ed5f70702.png)

Examples

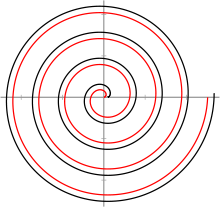

Involute of a circle

unwinding a string

The involute of a circle resembles, but is not, an Archimedean spiral.

Its successive turns are parallel curves with constant separation distance, a property which is often (inaccurately) ascribed to the Archimedean spiral.

- In Cartesian coordinates the involute of a circle has the parametric equation:

where  is the radius of the circle and

is the radius of the circle and  is an angle parameter in radians (

is an angle parameter in radians ( ) where for positive values of the angle parameter the righthand spiral is formed, and for negative values the lefthand spiral.

) where for positive values of the angle parameter the righthand spiral is formed, and for negative values the lefthand spiral.

- In polar coordinates

the involute of a circle has the parametric equation:

the involute of a circle has the parametric equation:

where  is the radius of the circle and

is the radius of the circle and  is an angle parameter in radians (

is an angle parameter in radians ( ) equal to

) equal to  (so

(so  ).

).

With that parameter  with

with  it can be written in the form:

it can be written in the form:

-

.

.

Curve length

The arc length of the above curve for  is

is

Application

Leonhard Euler proposed to use the involute of the circle for the shape of the teeth of toothwheel gear, a design which is the prevailing one in current use, called involute gear.

Involute of a catenary

The involute of a catenary through its vertex is a tractrix. In cartesian coordinates the curve follows:

Where: t is a parameter and sech is the hyperbolic secant (1/cosh(t))

Derivative

With

we have

and  .

.

Substitute

to get  .

.

Involute of a cycloid

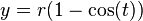

One involute of a cycloid is a congruent cycloid. In cartesian coordinates the curve follows:

Where t is the angle and r is the radius

Application

The involute has some properties that makes it extremely important to the gear industry: If two intermeshed gears have teeth with the profile-shape of involutes (rather than, for example, a "classic" triangular shape), they form an involute gear system. Their relative rates of rotation are constant while the teeth are engaged, and also, the gears always make contact along a single steady line of force. With teeth of other shapes, the relative speeds and forces rise and fall as successive teeth engage, resulting in vibration, noise, and excessive wear. For this reason, nearly all modern gear teeth bear the involute shape.

The involute of a circle is also an important shape in gas compressing, as a scroll compressor can be built based on this shape. Scroll compressors make less sound than conventional compressors, and have proven to be quite efficient.

See also

References

- ↑ John McCleary – Geometry from a Differentiable Viewpoint / Cambridge University Press, 1995 / pg. 73

External links

- Mathworld

- Application of the involute to gear teeth - a short historical account

| |||||||||||||||||