Integer

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

Modular groups

|

Infinite dimensional Lie group

|

An integer is a number that can be written without a fractional or decimal component. For example, 21, 4, and −2048 are integers; 9.75, 5½, and √2 are not integers. The set of integers is a subset of the real numbers, and consists of the natural numbers (1, 2, 3, ...), zero (0) and the negatives of the natural numbers (−1, −2, −3, ...).

The name derives from the Latin integer (meaning literally "untouched," hence "whole": the word entire comes from the same origin, but via French[1]). The set of all integers is often denoted by a boldface Z (or blackboard bold  , Unicode U+2124 ℤ), which stands for Zahlen (German for numbers, pronounced [ˈtsaːlən]).[2][3]

, Unicode U+2124 ℤ), which stands for Zahlen (German for numbers, pronounced [ˈtsaːlən]).[2][3]

The integers (with addition as operation) form the smallest group containing the additive monoid of the natural numbers. Like the natural numbers, the integers form a countably infinite set. In algebraic number theory, these commonly understood integers, embedded in the field of rational numbers, are referred to as rational integers to distinguish them from the more broadly defined algebraic integers.

The integers (with addition and multiplication addition) form a unital ring which is the most basic one, in the following sense: for any unital ring, there is a unique ring homomorphism from the integers into this ring. This universal property characterizes the integers.

Algebraic properties

Like the natural numbers, Z is closed under the operations of addition and multiplication, that is, the sum and product of any two integers is an integer. However, with the inclusion of the negative natural numbers, and, importantly, 0, Z (unlike the natural numbers) is also closed under subtraction. Z is not closed under division, since the quotient of two integers (e.g., 1 divided by 2), need not be an integer. Although the natural numbers are closed under exponentiation, the integers are not (since the result can be a fraction when the exponent is negative).

The following lists some of the basic properties of addition and multiplication for any integers a, b and c.

| Addition | Multiplication | |

|---|---|---|

| Closure: | a + b is an integer | a × b is an integer |

| Associativity: | a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c | a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c |

| Commutativity: | a + b = b + a | a × b = b × a |

| Existence of an identity element: | a + 0 = a | a × 1 = a |

| Existence of inverse elements: | a + (−a) = 0 | An inverse element usually does not exist at all. |

| Distributivity: | a × (b + c) = (a × b) + (a × c) and (a + b) × c = (a × c) + (b × c) | |

| No zero divisors: (*) | If a × b = 0, then a = 0 or b = 0 (or both) | |

In the language of abstract algebra, the first five properties listed above for addition say that Z under addition is an abelian group. As a group under addition, Z is a cyclic group, since every non-zero integer can be written as a finite sum 1 + 1 + ... + 1 or (−1) + (−1) + ... + (−1). In fact, Z under addition is the only infinite cyclic group, in the sense that any infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to Z.

The first four properties listed above for multiplication say that Z under multiplication is a commutative monoid. However not every integer has a multiplicative inverse; e.g. there is no integer x such that 2x = 1, because the left hand side is even, while the right hand side is odd. This means that Z under multiplication is not a group.

All the rules from the above property table, except for the last, taken together say that Z together with addition and multiplication is a commutative ring with unity. It is the prototype of all objects of such algebraic structure. Only those equalities of expressions are true in Z for all values of variables, which are true in any unital commutative ring.

At last, the property (*) says that the commutative ring Z is an integral domain. In fact, Z provides the motivation for defining such a structure.

The ring Z is the initial ring with unity, which means that it homomorphically maps to any such ring. Any integer number exists in any unital ring, with all arithmetic equalities on integers satisfied, although certain non-zero integers map to zero for certain rings.

The lack of multiplicative inverses, which is equivalent to the fact that Z is not closed under division, means that Z is not a field. The smallest field with the usual operations containing the integers is the field of rational numbers. The process of constructing the rationals from the integers can be mimicked to form the field of fractions of any integral domain. And back, starting from an algebraic number field (an extension of rational numbers), its ring of integers can be extracted, which includes Z as its subring.

Although ordinary division is not defined on Z, the division "with remainder" is defined on them. It is called Euclidean division and possesses the following important property: that is, given two integers a and b with b ≠ 0, there exist unique integers q and r such that a = q × b + r and 0 ≤ r < | b |, where | b | denotes the absolute value of b. The integer q is called the quotient and r is called the remainder of the division of a by b. The Euclidean algorithm for computing greatest common divisors works by a sequence of Euclidean divisions.

Again, in the language of abstract algebra, the above says that Z is a Euclidean domain. This implies that Z is a principal ideal domain and any positive integer can be written as the products of primes in an essentially unique way. This is the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

Order-theoretic properties

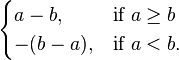

Z is a totally ordered set without upper or lower bound. The ordering of Z is given by:

- ... −3 < −2 < −1 < 0 < 1 < 2 < 3 < ...

An integer is positive if it is greater than zero and negative if it is less than zero. Zero is defined as neither negative nor positive.

The ordering of integers is compatible with the algebraic operations in the following way:

- if a < b and c < d, then a + c < b + d

- if a < b and 0 < c, then ac < bc.

It follows that Z together with the above ordering is an ordered ring.

The integers are the only integral domain whose positive elements are well-ordered, and in which order is preserved by addition.

Construction

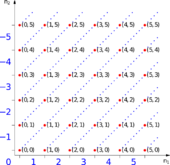

The integers can be formally constructed as the equivalence classes of ordered pairs of natural numbers (a,b).[4]

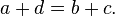

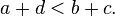

The intuition is that (a,b) stands for the result of subtracting b from a.[4] To confirm our expectation that 1 − 2 and 4 − 5 denote the same number, we define an equivalence relation ~ on these pairs with the following rule:

precisely when

Addition and multiplication of integers can be defined in terms of the equivalent operations on the natural numbers;[4] denoting by [(a,b)] the equivalence class having (a,b) as a member, one has:

The negation (or additive inverse) of an integer is obtained by reversing the order of the pair:

Hence subtraction can be defined as the addition of the additive inverse:

The standard ordering on the integers is given by:

It is easily verified that these definitions are independent of the choice of representatives of the equivalence classes.

Every equivalence class has a unique member that is of the form (n,0) or (0,n) (or both at once). The natural number n is identified with the class [(n,0)] (in other words the natural numbers are embedded into the integers by map sending n to [(n,0)]), and the class [(0,n)] is denoted −n (this covers all remaining classes, and gives the class [(0,0)] a second time since −0 = 0.

Thus, [(a,b)] is denoted by

If the natural numbers are identified with the corresponding integers (using the embedding mentioned above), this convention creates no ambiguity.

This notation recovers the familiar representation of the integers as {... −3,−2,−1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...}.

Some examples are:

Integers in computing

An integer is often a primitive data type in computer languages. However, integer data types can only represent a subset of all integers, since practical computers are of finite capacity. Also, in the common two's complement representation, the inherent definition of sign distinguishes between "negative" and "non-negative" rather than "negative, positive, and 0". (It is, however, certainly possible for a computer to determine whether an integer value is truly positive.) Fixed length integer approximation data types (or subsets) are denoted int or Integer in several programming languages (such as Algol68, C, Java, Delphi, etc.).

Variable-length representations of integers, such as bignums, can store any integer that fits in the computer's memory. Other integer data types are implemented with a fixed size, usually a number of bits which is a power of 2 (4, 8, 16, etc.) or a memorable number of decimal digits (e.g., 9 or 10).

Cardinality

The cardinality of the set of integers is equal to  (aleph-null). This is readily demonstrated by the construction of a bijection, that is, a function that is injective and surjective from Z to N.

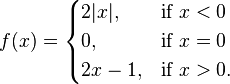

If N = {0, 1, 2, ...} then consider the function:

(aleph-null). This is readily demonstrated by the construction of a bijection, that is, a function that is injective and surjective from Z to N.

If N = {0, 1, 2, ...} then consider the function:

{... (-4,8) (-3,6) (-2,4) (-1,2) (0,0) (1,1) (2,3) (3,5) ...}

If N = {1, 2, 3, ...} then consider the function:

{... (-4,8) (-3,6) (-2,4) (-1,2) (0,1) (1,3) (2,5) (3,7) ...}

If the domain is restricted to Z then each and every member of Z has one and only one corresponding member of N and by the definition of cardinal equality the two sets have equal cardinality.

See also

- 0.999...

- Algebraic integer

- Canonical representation of a positive integer

- Hyperinteger

- Integer (computer science)

- Integer lattice

- Integer part

- Integer sequence

Notes

- ↑ Evans, Nick (1995). "A-Quantifiers and Scope". In Bach, Emmon W. Quantification in Natural Languages. Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 262. ISBN 0-7923-3352-7.

- ↑ Miller, Jeff (2010-08-29). "Earliest Uses of Symbols of Number Theory". Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ Peter Jephson Cameron (1998). Introduction to Algebra. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-850195-4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Campbell, Howard E. (1970). The structure of arithmetic. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 83. ISBN 0-390-16895-5.

References

- Bell, E.T., Men of Mathematics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986. (Hardcover; ISBN 0-671-46400-0)/(Paperback; ISBN 0-671-62818-6)

- Herstein, I.N., Topics in Algebra, Wiley; 2 edition (June 20, 1975), ISBN 0-471-01090-1.

- Mac Lane, Saunders, and Garrett Birkhoff; Algebra, American Mathematical Society; 3rd edition (April 1999). ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Integer", MathWorld.

External links

| Look up integer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Integer", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- The Positive Integers — divisor tables and numeral representation tools

- On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences cf OEIS

This article incorporates material from Integer on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![[(a,b)]+[(c,d)]:=[(a+c,b+d)].\,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/f/3/3/bf337cc180aaafed2c987a227b799e47.png)

![[(a,b)]\cdot [(c,d)]:=[(ac+bd,ad+bc)].\,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/8/8/6/28866cf8c27afb7c817dc2d64fcbbd58.png)

![-[(a,b)]:=[(b,a)].\,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/0/c/c/a/0cca34240f5c542ab8397f1b9a9a55ff.png)

![[(a,b)]-[(c,d)]:=[(a+d,b+c)].\,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/2/d/5/92d53b5e8a5cac307bcf01f3f798b402.png)

![[(a,b)]<[(c,d)]\,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/d/2/0/cd20ff73f10fdb26cb05a241b4888d03.png)

![{\begin{aligned}0&=[(0,0)]&=[(1,1)]&=\cdots &&=[(k,k)]\\1&=[(1,0)]&=[(2,1)]&=\cdots &&=[(k+1,k)]\\-1&=[(0,1)]&=[(1,2)]&=\cdots &&=[(k,k+1)]\\2&=[(2,0)]&=[(3,1)]&=\cdots &&=[(k+2,k)]\\-2&=[(0,2)]&=[(1,3)]&=\cdots &&=[(k,k+2)].\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/c/7/2/1c72a33a064c334c308c4c8ea4539b15.png)

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)