Incidence geometry

In mathematics, incidence geometry is the study of incidence structures. A geometry such as the Euclidean plane is a complicated object involving concepts such as length, angles, continuity, betweenness and incidence. An incidence structure is what is obtained when all the other concepts are removed and all that remains is the data about which points lie on which lines. Even with this severe limitation, theorems can be proved and interesting facts emerge concerning this structure. Such fundamental results remain valid when additional concepts are added back to form a richer geometry. It sometimes happens that authors will blur the distinction between a study and the objects of that study, so it is not surprising to find that some authors will refer to incidence structures as incidence geometries.[1]

Definition

An incidence structure (P, L, I) consists of a set P whose elements are called points, a disjoint set L whose elements are called lines and an incidence relation I between them, that is, a subset of P × L.[2] Intuitively, a point and line are in this relation if and only if the point is on the line.

Incidence structures that are most studied are those that satisfy some additional properties (axioms), such as projective planes, affine planes, and polar spaces. Very general incidence structures can be obtained by imposing "mild" conditions, such as:

A partial linear space is an incidence structure for which the following axioms are true:[3]

- Every pair of distinct points determines at most one line.

- Every line contains at least two distinct points.

A linear space is a partial linear space such that:[4]

- Every pair of distinct points determines exactly one line.

Some authors would add a "non-triviality" axiom to the definition of a (partial) linear space, such as:

- There exist at least two distinct lines.[5]

This is used to rule out some very small examples (mainly when the sets P or L have fewer than two elements) that would normally be exceptions to general statements made about the incidence structures. An alternative to adding the axiom is to refer to incidence structures which do not satisfy the axiom as being trivial and those that do as non-trivial.

Each non-trivial linear space contains at least three points and three lines, so the simplest non-trivial linear space that can exist may be represented by:

Fano plane

One famous incidence geometry was developed by the Italian mathematician Gino Fano. In his work[6] on proving the independence of the set of axioms for projective n-space that he developed,[7] he produced a finite three dimensional space with 15 points, 35 lines and 15 planes, in which each line had only three points on it.[8] The planes in this space consisted of seven points and seven lines and are now known as Fano planes:

Incidence matrix

A finite incidence geometry (one with a finite number of points and lines) is equivalent to an incidence matrix which gives a visual representation of all the incidence relations in the geometry. The rows of the matrix represent points, while the columns represent lines. An entry of one in row i and column j means that the point i is incident with the line j. All other entries are zero. The incidence matrix for the Fano plane looks like this:

The incidence matrix contains all the information that is known about an incidence geometry. Being an algebraic object it may be studied with algebraic tools thus opening an avenue for obtaining additional information about the geometry.

Line–Line matrix

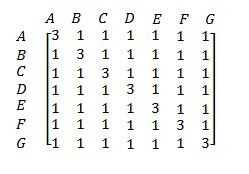

The line–line matrix indicates the number of common points for each line-pair. The line–line matrix for the Fano plane is:

The line–line matrix can be obtained from the incidence matrix. If N is the incidence matrix and NT is the transpose of the incidence matrix, then the line–line matrix is the matrix product, L = NT × N.

Point–Point matrix

The point–point matrix indicates the number of lines common to each point-pair. The point–point matrix for the Fano plane is as follows:

The point–point matrix can also be derived from the incidence matrix. If N is the incidence matrix and NT is the transpose of the incidence matrix, then the point–point matrix is the product P = N × NT.

The de Bruijn–Erdős theorem

The de Bruijn–Erdős theorem is a well known theorem in the field of incidence geometry. Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn and Paul Erdős proved the result. The theorem is:[9]

- In a projective plane, every non-collinear set of n points determines at least n distinct lines.

As the authors pointed out, since their proof was combinatorial, the result holds in a larger setting, in fact in any incidence geometry.

More examples

- Projective geometries

- Möbius geometries

- Near polygons

- Generalized polygons

See also

- Finite geometry

- Group theory

- Combinatorial designs

- Projective configuration

- Levi graph

Notes

- ↑ As, for example, L. Storme does in his chapter on Finite Geometry in Colbourn & Dinitz (2007, pg. 702)

- ↑ Technically this is a rank two incidence structure, where rank refers to the number of types of objects under consideration (here, points and lines). Higher ranked structures are also studied, but several authors limit themselves to the rank two case, as shall we.

- ↑ Moorhouse, pg.5

- ↑ Moorhouse, pg. 5

- ↑ There are several alternatives for this "non-triviality" axiom. This could be replaced by "there exist three points not on the same line" as is done in Batten & Beutelspacher (1993, pg. 1). There are other choices, but they must always be existence statements that rule out the very simple cases which are to be excluded.

- ↑ Fano, G. (1892), "Sui postulati fondamentali della geometria proiettiva", Giornale di Matematiche 30: 106–132

- ↑ Collino, Conte & Verra 2013, p. 6

- ↑ Malkevitch Finite Geometries? an AMS Featured Column

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "de Bruijn–Erdős Theorem" from MathWorld

References

- Batten, Lynn Margaret (1986), Combinatorics of Finite Geometries, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31857-2

- Collino, Alberto; Conte, Alberto; Verra, Alessandro (2013). "On the life and scientific work of Gino Fano". arXiv:1311.7177.

- Buekenhout, Francis (1995), Handbook of Incidence Geometry: Buildings and Foundations, Elsevier B.V.

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd ed.), Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC, ISBN 1-58488-506-8

- Malkevitch, Joe. "Finite Geometries?". Retrieved Dec 2, 2013.

- Moorhouse, G. Eric. "Incidence Geometry". Retrieved Oct 20, 2012.

- Johannes Ueberberg: Foundations of Incidence Geometry. Springer 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-20972-7