Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by the Dictionary of Human Geography, is "an unequal human and territorial relationship, usually in the form of an empire, based on ideas of superiority and practices of dominance, and involving the extension of authority and control of one state or people over another."[1] Lewis Samuel Feuer identifies two major subtypes of imperialism; the first is the "regressive imperialism" identified with pure conquest, unequivocal exploitation, extermination or reductions of undesired peoples, and settlement of desired peoples into those territories.[2] The second type identified by Feuer is "progressive imperialism" that is founded upon a cosmopolitan view of humanity, that promotes the spread of civilization to allegedly "backward" societies to elevate living standards and culture in conquered territories, and allowance of a conquered people to assimilate into the imperial society, an example being the cosmopolitan Roman Empire.[2]

The term as such primarily has been applied to Western political and economic dominance in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some writers, such as Edward Said, use the term more broadly to describe any system of domination and subordination organized with an imperial center and a periphery.[3] According to Marxist theorist Vladimir Lenin, imperialism is a natural feature of a developed capitalist nation state as it matures into monopoly capitalism. In his work Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin observed that as capitalism matured in the Western world, the economy shifted away from real commodity production towards banking and finance, as commodity production was outsourced to the empires' colonies. Lenin concluded that the competition between empires and the unfettered drive to maximise profit would lead to wars between the empires themselves, such as World War I in his contemporary time, as well as continued future military invasions and occupations in the undeveloped world to establish and expand markets and exploit cheap labour for the monopolist corporations of the empires.

It is mostly accepted that modern-day colonialism is an expression of imperialism and cannot exist without the latter. The extent to which "informal" imperialism with no formal colonies is properly described as such remains a controversial topic among historians.[4]

The word imperialism became common in the United Kingdom in the 1870s and was used with a negative connotation.[5] In Great Britain, the word had until then mostly been used to refer to the politics of Napoléon III of obtaining favorable public opinion in France through military interventions outside France.[5]

History

Imperialism has been found in the histories of Japan, the Assyrian Empire, the Chinese Empire, the Roman Empire, Greece, the Byzantine Empire, the Persian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, ancient Egypt, and India. Imperialism was a basic component to the conquests of Genghis Khan during the Mongol Empire, and other war-lords. Historically recognized Muslim empires number in the dozens. Sub-Saharan Africa has also had dozens of empires that pre-date the European colonial era, for example the Ethiopian Empire, Oyo Empire, Asante Union, Luba Empire, Lunda Empire and Mutapa Empire. The Americas during the pre-Columbian era also had large empires such as the Aztec and the Inca.

Although normally used to imply forcible imposition of a more powerful foreign government's control on a weaker country, or over conquered territory that was previously without a unified government, "imperialism" is sometimes also used to describe loose or indirect political or economic influence or control of weak states by more powerful ones.[6] If the dominant country's influence is felt in social and cultural circles, such as "foreign" music being popular with young people, it may be described as cultural imperialism.

"Imperialism has been subject to moral or imoral censure by its critics, and thus the term is frequently used in international propaganda as a pejorative for expansionist and aggressive foreign policy."[6]

Colonialism vs. Imperialism

The term "imperialism" should not be confused with "colonialism". Robert Young writes that imperialism operates from the center, it is a state policy, and is developed for ideological as well as financial reasons whereas colonialism is nothing more than development for settlement or commercial intentions.[7]

Age of Imperialism

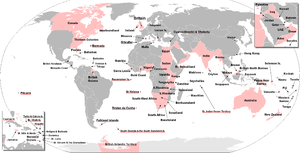

The Age of Imperialism was a time period beginning around 1700 when modern, relatively developed nations were taking over less developed areas, colonizing them, or influencing them in order to expand their own power. Although imperialist practices have existed for thousands of years, the term "Age of Imperialism" generally refers to the activities of nations such as the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States in the early 18th through the middle 20th centuries, e.g., the "The Great Game" in Persian lands, the "Scramble for Africa" and the "Open Door Policy" in China.[8][9]

The ideas of imperialism were put forward by historians John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson during the 20th century. European imperialism was influential, and Europeans rejected the notion that "imperialism" required formal, legal control by one government over another country. "In their view, historians have been mesmerized by formal empire and maps of the world with regions colored red. The bulk of British emigration, trade, and capital went to areas outside the formal British Empire. A key to the thought of Robinson and Gallagher is the idea of empire 'informally if possible and formally if necessary.'"[10] Because of British Imperialism, the world's economy grew before World War I, making Britain a dominant financial force.[11]

Europe’s expansion into territorial imperialism had much to do with the great economic benefit from collecting resources from colonies, in combination with assuming political control often by military means. Most notably, the “British exploited the political weakness of the Mughal state, and, while military activity was important at various times, the economic and administrative incorporation of local elites was also of crucial significance”. Although a substantial number of colonies had been designed or subject to provide economic profit (mostly through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries), Fieldhouse suggests that in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in places such as Africa and Asia, this idea is not necessarily valid:[12]

Modern empires were not artificially constructed economic machines. The second expansion of Europe was a complex historical process in which political, social and emotional forces in Europe and on the periphery were more influential than calculated imperialism. Individual colonies might serve an economic purpose; collectively no empire had any definable function, economic or otherwise. Empires represented only a particular phase in the ever-changing relationship of Europe with the rest of the world: analogies with industrial systems or investment in real estate were simply misleading.[13]

During this time, European merchants had the ability to “roam the high seas and appropriate surpluses from around the world (sometimes peaceably, sometimes violently) and to concentrate them in Europe.”[14]

European expansion accelerated greatly in the 19th century. To obtain raw materials, Europe began importing them from other countries. Europeans sought raw materials such as dyes, cotton, vegetable oils, and metal ores from overseas. Europe was being transformed into the manufacturing center of the world.[15]

Communication became much more advanced during the European expansion. The invention of railroads and telegraphs made it easier to communicate with other countries. Railroads assisted in transporting goods and in supplying large armies.[15]

Along with advancements in communication, Europe also continued to develop its military technology. European chemists made deadly explosives that could be used in combat, and with the advancement of machinery they were able to create lighter, cheaper guns. The guns were also much faster and more accurate. By the late 19th century (1880s) the machine gun had become an effective battlefield weapon. This technology gave European armies an advantage over their opponents, as armies in less developed countries were still fighting with arrows, swords, and leather shields.[15]

German imperialism

From their original homelands in Scandinavia and the far north of Europe, Germanic tribes expanded throughout northern and western Europe in the middle period of classical antiquity, and southern Europe in late antiquity, conquering Celtic and other peoples and forming in 800 the Holy Roman Empire, the first German Empire. However, there was no real systemic continuity from the western Roman Empire to its German successor which famously was "not holy, not Roman, and not an empire",[16] and numerous small states existed in variously autonomous confederation. Although by 1000 Germanic conquest of central, western, and southern Europe west of and including Italy was complete, excluding only Muslim Iberia, but there was little cultural integration and national identity, and "Germany" remained largely a conceptual term referring to an amorphous area of central Europe.

Not a maritime power, and not a nation-state, as it would eventually become, Germany's participation in Western imperialism was negligible until the late 19th century. Participation of Austria was primarily as a result of Habsburg control of the First Empire, the Spanish throne, and other royal houses. After the defeat of Napoleon, who caused the dissolution of that first German Empire, Prussia and the German states continued to stand aloof from imperialism, preferring to manipulate the European system through polices such as those of Metternich. After Prussia unified the other states into the second German Empire, its long-time leader Otto von Bismarck (1862–90) had long opposed colonial acquisitions, arguing that the burden of obtaining, maintaining and defending such possessions would outweigh any potential benefit. He felt that colonies did not pay for themselves, that the German bureaucratic system would not work well in the easy-going tropics, and the diplomatic disputes over colonies would distract Germany from its central interest, Europe itself.[17] However, in 1883-84 he suddenly reversed himself and overnight built a colonial empire in Africa and the South Pacific, and then lost interest in imperialism. Historians have debated exactly why he made this sudden and short-lived move.[18] He was aware that public opinion had started to demand colonies for reasons of German prestige.[19] Bismarck was influenced by Hamburg merchants and traders, his neighbors at Friedrichsruh. The establishment of the German colonial empire proceeded smoothly, starting with German New Guinea in 1884.[20]

After the collapse of the short-lived Third Reich, and the failure of its attempt to create a great land empire in Eurasia, Germany was split between Western and Soviet spheres of influence until Perestroika and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Tsarist and Soviet imperialism

In the 19th century, the Romanov Empire extended its control to the Pacific, forming a common border with the Qing Empire.

Bolshevik leaders had effectively reestablished a polity with roughly the same jurisdiction as that empire by 1921, but with an internationalist ideology: Lenin in particular asserted the right to self-determination for national minorities within the new territory.[21] Beginning in 1923, the policy of "Indigenization" [korenizatsiia] was intended to support non-Russians develop their national cultures within a socialist framework. Never formally revoked, it stopped being implemented after 1932. After World War II, the Soviet Union installed socialist regimes modelled on those it had installed in 1919–20 in the old Tsarist Empire in areas its forces occupied in Eastern Europe.[22] The Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China supported post–World War II anti-colonial national-liberation movements to advance their own interests but were not always successful.[23]

Trotsky, and others, believed that the revolution could only succeed in Russia as part of a world revolution, which was in fact, shortly after the Russian Revolution, spreading in the defeated Central Powers of Europe. Lenin wrote extensively on the matter and famously declared that Imperialism was the highest stage of capitalism. However, after Lenin's death, Joseph Stalin established 'socialism in one country' for the Soviet Union, creating the model for subsequent inward looking Stalinist states and purging the early Internationalist elements. The internationalist tendencies of the early revolution would be abandoned until they returned in a client state form in the competition with the United States in the Cold War.

Though the Soviet Union declared itself anti-imperialist, critics argue that it exhibited tendencies common to historic empires.[24][25] Some scholars hold that the Soviet Union was a hybrid entity containing elements common to both multinational empires and nation states. It has also been argued that the USSR practiced colonialism as did other imperial powers and was carrying on the old Russian tradition of expansion and control.[26]

Japanese imperialism

During the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Japan absorbed Taiwan. As a result of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Japan took part of Sakhalin Island from Russia. Korea was annexed in 1910. During World War I Japan took German-leased territories in China's Shandong Province, as well as the Marianas, Caroline, and Marshall Islands. In 1918, Japan occupied parts of Far Eastern Russia and parts of eastern Siberia as a participant in the Siberian Intervention. In 1931 Japan conquered Manchuria. During the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, it invaded China. By the end of the Pacific War, Japan had conquered most of the Far East, including what is now Hong Kong, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, the Philippine Islands, Indonesia, New Guinea and many islands of the Pacific Ocean.[27][28][29]

American imperialism

The early United States expressed its opposition to Imperialism, at least that distinct from its own Manifest Destiny, in policies such as the Monroe Doctrine. Beginning in the late 19th and early 20th century, however, policies such as Woodrow Wilson's mission to "make the world safe for democracy"[30] were often backed by military force, but more often effected from behind the scenes, consistent with the general notion of hegemony and imperium of historical empires.[31][32] In 1898, Americans who opposed imperialism created the Anti-Imperialist League to oppose the US annexation of the Philippines and Cuba. A year later a war erupted in the Philippines causing business, labor and government leaders in the US to condemn America's occupation in the Philippines. They also denounced them for causing the deaths of many Filipinos.[33] American foreign policy was denounced as a "racket" by Smedley Butler, an American general. He said, "Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents."[34]

After the Second World War, the United States became joined with Western interests in a global conflict over spheres of influence with the Soviet Union, known as the Cold War. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States did not diminish its global ability to project force and became "the sole superpower". A system of "Unipolarity" came to define international politics, with the United States at the center.

Since the end of the previous century Battlespace domination has been an open and variously reported policy of the U.S. Department of Defense and U.S. Administrations stated and restated in various Quadrennial Reports, force posture statements, etc. in execution of its role as sole remaining superpower.[35][36] The 2010 QDR indicates a change in perspective and it is unclear how the policy of the first decade of the 21st century would be sustained through the anticipated fiscal environment of the second.[37]

In 2005, the United States had 737 military bases in foreign countries, according to official sources.[38] In 2010, the U.S. spent as much on its military as the 17 next biggest spending countries combined, most of whom were U.S. allies.[39]

Justification

A controversial aspect of imperialism is the imperial power’s defense and justification of such actions. Most controversial of all is the justification of imperialism done on rational grounds. J. A. Hobson identifies this justification: “It is desirable that the earth should be peopled, governed, and developed, as far as possible, by the races which can do this work best, i.e. by the races of highest 'social efficiency'.”[40]

Technological and economic efficiency were often improved in territories subjected to imperialism through the building of roads, other infrastructure and introduction of innovations. A common argument against this is that such infrastrural improvements would have occurred anyway if the conquered territory were left to its own devices, and as a colony the benefits go to the imperial power rather than the territory itself. Imperialism by many different states throughout history has been one factor in the spread of the scientific method, as science was one factor that made these states stronger than their competitors.[41]

The principles of imperialism are often deeply connected to the policies and practices of British Imperialism "during the last generation, and proceeds rather by diagnosis than by historical description."[42] British Imperialist strategy often but not always used the concept of terra nullius (Latin expression which stems from Roman law meaning ‘empty land’). The country of Australia serves as a case study in relation to British imperialism. British settlement and colonial rule of the island continent of Australia in the eighteenth century was premised on terra nullius, for its settlers considered it unused by its sparse inhabitants.

This form of imperialism can also be seen in British Columbia, Canada. In the 1840s, the territory of British Columbia was divided into two regions, one space for the native population, and the other for non-natives. The indigenous peoples were often forcibly removed from their homes onto reserves. These actions were “justified by a dominant belief among British colonial officials that land occupied by Native people was not being used efficiently and productively.”[7]

See also

- Colonialism

- Cultural imperialism

- Empire

- Globalization

- Hegemony

- Imperialism in Leninist theory

- Imperium

- Imperialism (video game)

- International relations (1814–1919)

- John A. Hobson

- List of empires

- List of largest empires

- Neocolonialism

- New Imperialism

- Oil imperialism theories

- Pluricontinental

- Scientific imperialism

- Super-imperialism

- Ultra-imperialism

- Uneven and combined development

References

- ↑ Gregory, Derek, Johnston, Ron, Prattt, Geraldine, Watts, Michael J., and Whatmore, Sarah (2009). The Dictionary of Human Geography (5th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 373. ISBN 978-14051-3288-6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lewis Samuel Feuer. Imperialism and the Anti-Imperialist Mind. Transaction Publishers, 1989. P. 4.

- ↑ Edward W. Said. Culture and Imperialism. Vintage Publishers, 1994. P. 9.

- ↑ Barbara Bush (2006). Imperialism And Postcolonialism. Pearson Longman. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-582-50583-4. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Magnusson, Lars (1991). Teorier om imperialism (in Swedish). Södertälje. p. 19. ISBN 91-550-3830-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Imperialism." 'International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd edition.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gilmartin, Mary. Gallaher, C. et al., 2008. Key Concepts in Political Geography, Sage Publications Ltd. : Imperialism/Colonialism. pg.116

- ↑ "The Age of Imperialism, 1850–1914". Google docs. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ↑ "The United States and its Territories: 1870–1925 The Age of Imperialism". University of Michigan. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ↑ Louis, Wm. Roger. (1976) Imperialism page 4.

- ↑ Christopher, A.J. (1985). "Patterns of British Overseas Investment in Land". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. New Series 10 (4): 452–466.

- ↑ Painter, J. & Jeffrey, A., 2009. Political Geography 2nd ed., Sage. pg.183-184

- ↑ Painter, J. & Jeffrey, A., 2009. Political Geography 2nd ed., Sage. pg.184

- ↑ Harvey, D., 2006. Spaces of Global Capitalism: A Theory of Uneven Geographical Development, Verso. pg. 91

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Adas, Michael; Peter N. Stearns (2008). Turbulent Passage A Global History of the Twentieth Century (Fourth Edition ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 54–58. ISBN 0-205-64571-2.

- ↑ attributed to Voltaire

- ↑ Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876-1912 (1992) ch 12

- ↑ Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 (1988) ch 10

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler, "Bismarck's Imperialism 1862–1890," Past & Present, (1970) 48: 119–55 online

- ↑ Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, "Domestic Origins of Germany's Colonial Expansion under Bismarck" Past & Present (1969) 42:140–159 online; Crankshaw, pp. 395–7

- ↑ V.I. Lenin (1913). Critical Remarks on the National Question. Prosveshcheniye.

- ↑ "The Soviet Union and Europe after 1945". The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page (2003). Colonialism: an international social, cultural, and political encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Beissinger, Mark R. 2006 "Soviet Empire as 'Family Resemblance,'" Slavic Review, 65 (2) 294-303; Dave, Bhavna. 2007 Kazakhstan: Ethnicity, language and power. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/pss/20031013 Foreign Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 1, Oct., 1953 - Soviet Colonialism In Central Asia by Sir Olaf Caroe

- ↑ Caroe, O. (1953). "Soviet Colonialism in Central Asia". Foreign Affairs 32 (1): 135–144. JSTOR 20031013.

- ↑ Joseph A. Mauriello. "Japan and The Second World War: The Aftermath of Imperialism". Lehigh University. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945". National University of Singapore. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ "The Japanese Empire 1942". The History Place. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ Text of Original address (mtholyoke.edu)

- ↑ Boot, Max (July 15, 2004). "In Modern Imperialism, U.S. Needs to Walk Softly". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ↑ Oliver Kamm (October 30, 2008). "America is still the world's policeman". The Times.

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=QKgraWbb7yoC&pg=PA1075#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Moore: War is just a racket, said a General in 1933

- ↑ Quadrennial Review 1997

- ↑ 2006 QDR

- ↑ Current QDR (2012)

- ↑ Chalmers Johnson (February 19, 2007). "737 U.S. Military Bases = Global Empire". AlterNet.

- ↑ R.M. (December 1, 2011). "Always more, or else". The Economist.

- ↑ Hobson, J. A. "Imperialism: a study." Cosimo, Inc., 2005. pg. 154

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=L5wdAAAAIAAJ&lpg=PA243&ots=Krjpr-iAPF&dq=scientific%20revolution%20british%20imperialism&pg=PA243#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Hobson, J. A. "Imperialism: a study." Cosimo, Inc., 2005. pg. V

Further reading

- Guy Ankerl, Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharatai, Chinese, and Western, Geneva, INU PRESS, 2000, ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Robert Bickers/Christian Henriot, New Frontiers: Imperialism's New Communities in East Asia, 1842–1953, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7190-5604-7

- Leo Blanken, Rational Empires: Institutional Incentives and Imperial Expansion, University Of Chicago Press, 2012

- Barbara Bush, Imperialism and Postcolonialism (History: Concepts,Theories and Practice), Longmans, 2006, ISBN 0-582-50583-6

- John Darwin (author), After Tamerlane: The Rise and Fall of Global Empires, 1400–2000, Penguin Books, 2008.

- Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido (ed. and trans.), Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012.

- Niall Ferguson, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, Penguin Books, 2004, ISBN 0-14-100754-0

- Michael Hardt and Toni Negri, Empire, Harvard University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-674-00671-2

- E.J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire, 1875–1914, Abacus Books, 1989, ISBN 0-349-10598-7

- E. J. Hobsbawm, On Empire: America, War, and Global Supremacy, Pantheon Books, 2008, ISBN 0-375-42537-3

- J. A. Hobson, Imperialism: A Study, Cosimo Classics, 2005, ISBN 1-59605-250-3

- Michael Hudson, Super Imperialism: The Origin and Fundamentals of U.S. World Dominance, Pluto Press, 2003, ISBN 0-7453-1989-0

- Hodge, Carl Cavanagh. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1914 (2 vol. 2007)

- Page, Melvin E. et al. eds. Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia (2 vol 2003)

- Pakenham, Thomas. The Scramble for Africa: White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876-1912 (1992)

- Petringa, Maria, Brazza, A Life for Africa, Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism, Vintage Books, 1998, ISBN 0-09-996750-2

- Simon C. Smith, British Imperialism 1750–1970, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-521-59930-X

- Benedikt Stuchtey, Colonialism and Imperialism, 1450-1950, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2011

- E.M. Winslow, "Marxian, Liberal, and Sociological Theories of Imperialism," Journal of Political Economy, vol. 39, no. 6 (Dec. 1931), pp. 713–758. In JSTOR

Primary sources

- V. I. Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, International Publishers, New York, 1997, ISBN 0-7178-0098-9

- Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital: A Contribution to an Economic Explanation of Imperialism

External links

- J.A Hobson, Imperialism a Study 1902.

- The Paradox of Imperialism by Hans-Hermann Hoppe. November 2006.

- Imperialism Quotations

- State, Imperialism and Capitalism by Joseph Schumpeter

- Economic Imperialism by A.J.P.Taylor

- Imperialism Entry in the Columbia Encyclopedia (Bartleby)

- Imperialism by Emile Perreau-Saussine

- The Nation-State, Core and Periphery: A Brief sketch of Imperialism in the 20th century.

- Mehmet Akif Okur, Rethinking Empire After 9/11: Towards A New Ontological Image of World Order, Perceptions, Journal of International Affairs, Volume XII, Winter 2007, pp.61–93

- Imperialism 101, Against Empire By Michael Parenti Published by City Lights Books, 1995, ISBN 0-87286-298-4, ISBN 978-0-87286-298-2, 217 pages

| |||||||||||||||||