Ichthyoplankton

.jpg)

Ichthyoplankton (from Greek: ἰχθύς, ikhthus, "fish"; and πλαγκτός, planktos, "drifter"[1]) are the eggs and larvae of fish. They are usually found in the sunlit zone of the water column, less than 200 metres deep, which is sometimes called the epipelagic or photic zone. Ichthyoplankton are planktonic, meaning they cannot swim effectively under their own power, but must drift with the ocean currents. Fish eggs cannot swim at all, and are unambiguously planktonic. Early stage larvae swim poorly, but later stage larvae swim better and cease to be planktonic as they grow into juveniles. Fish larvae are part of the zooplankton that eat smaller plankton, while fish eggs carry their own food supply. Both eggs and larvae are themselves eaten by larger animals.[2][3]

Fish can produce high numbers of eggs which are often released into the open water column. Fish eggs typically have a diameter of about 1 millimetre (0.039 in). The newly hatched young of oviparous fish are called larvae. They are usually poorly formed, carry a large yolk sac (for nourishment) and are very different in appearance from juvenile and adult specimens. The larval period in oviparous fish is relatively short (usually only several weeks), and larvae rapidly grow and change appearance and structure (a process termed metamorphosis) to become juveniles. During this transition larvae must switch from their yolk sac to feeding on zooplankton prey, a process which depends on typically inadequate zooplankton density, starving many larvae.

Ichthyoplankton can be a useful indicator of the state and health of an aquatic ecosystem.[2] For instance, most late stage larvae in ichthyoplankton have usually been predated, so ichthyoplankton tends to be dominated by eggs and early stage larvae. This means that when fish, such as anchovies and sardines, are spawning, ichthyoplankton samples can reflect their spawning output and provide an index of relative population size for the fish.[3] Increases or decreases in the number of adult fish stocks can be detected more rapidly and sensitively by monitoring the ichthyoplankton associated with them, compared to monitoring the adults themselves. It is also usually easier and more cost effective to sample trends in egg and larva populations than to sample trends in adult fish populations.[3]

History

Interest in plankton originated in Britain and Germany in the nineteenth century when researchers discovered there were microorganisms in the sea, and that they could trap them with fine-mesh nets. They started describing these microorganisms and testing different net configurations.[3] Ichthyoplankton research started in 1864 when the Norwegian government commissioned the marine biologist G. O. Sars to investigate fisheries around the Norwegian coast. Sars found fish eggs, particularly cod eggs, drifting in the water. This established that fish eggs could be pelagic, living in the open water column like other plankton.[4] Around the beginning of the twentieth century, research interest in ichthyoplankton became more general when it emerged that, if ichthyoplankton was sampled quantitatively, then the samples could indicate the relative size or abundance of spawning fish stocks.[3]

Sampling methods

Research vessels collect ichthyoplankton from the ocean using fine mesh nets. The vessels either tow the nets through the sea or pump sea water onboard and then pass it through the net.[5]

- There are many types of plankton tows:[5]

- Neuston net tows are often made at or just below the surface using a nylon mesh net fitted to a rectangular frame

- The PairoVET tow, used for collecting fish eggs, drops a net about 70 metres into the sea from a stationary research vessel and then drags it back to the vessel.

- Ring net tows involve a nylon mesh net fitted to a circular frame. These have largely been replaced by bongo nets, which provide duplicate samples with their dual-net design.

- The bongo tow drags nets shaped like bongo drums from a moving vessel. The net is often lowered to about 200 metres and then allowed to rise to the surface as it is towed. In this way, a sample can be collected across the whole photic zone where most ichthyoplankton is found.

- MOCNESS tows and Tucker trawls utilize multiple nets that are mechanically opened and closed at discrete depths in order to provide insights into the vertical distribution of the plankton

- The manta trawl tows a net from a moving vessel along the surface of the water, collecting larvae, such as grunion, mahi-mahi, and flying fish which live at the surface.

- After the tow the plankton is flushed with a hose to the cod end (bottom) of the net for collection. The sample is then placed in preservative fluid prior to being sorted and identified in a laboratory.[5]

- Plankton pumps: Another method of collecting ichthyoplankton is to use a Continuous Underway Fish Egg Sampler (CUFES). Water from a depth of about three metres is pumped onto the vessel and filtered with a net. This method can be used while the vessel is underway.[5]

Developmental stages

Ichthyoplankton researchers generally use the terminology and development stages introduced in 1984 by Kendall and others.[3] This consists of three main developmental stages and two transitional stages.[6]

| |

Salmon egg hatching. The larva has broken through and is discarding the egg envelope. In about 24hrs it will absorb the remaining yolk sac and become a juvenile. | ||||

| Main stages | Egg stage | Spawning to hatching. This stage is used instead of using an embryonic stage because there are aspects, such as those to do with the egg envelope, that are not just embryonic aspects. | |||

| Larval stage | From hatching till all fin rays are present and the growth of fish scales has started (squamation). A key event is when the notochord associated with the tail fin on the ventral side of the spinal cord develops flexion (becomes flexible). | The larval stage can be further subdivided into preflexion, flexion, and postflexion stages. In many species, the body shape and fin rays, as well as the ability to move and feed, develops most rapidly during the flexion stage. | |||

| Juvenile stage | Starts with all the fin rays being present and scale growth underway, and completes when the juvenile becomes sexually mature or starts interacting with other adults. | ||||

| Transitional stages | Yolk-sac larval stage | From hatching to absorption of the yolk-sac | |||

| Transformation stage | From larva to juvenile. This metamorphosis is complete when the larva develops the features of a juvenile fish. | ||||

Survival

Recruitment of fish is regulated by larval fish survival. Survival is regulated by prey abundance, predation, and hydrology. Fish eggs and larvae are eaten by many marine organisms.[7] For example, they may be fed upon by marine invertebrates, such as copepods, arrow worms, jellyfish, amphipods, marine snails and krill.[8][9] Because they are so abundant, marine invertebrates inflict high overall mortality rates.[10] Adult fish also predate fish eggs and larvae. For example, haddock were observed satiating themselves with herring eggs back in 1922.[8] Another study found cod in a herring spawning area with 20,000 herring eggs in their stomachs, and concluded that they could predate half of the total egg production.[11] Fish also cannibalise their own eggs. For example, separate studies found northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax) were responsible for 28% of the mortality in their own egg population,[12] while Peruvian anchoveta were responsible for 10%[12] and South African anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) 70%.[7]

The most effective predators are about ten times as long as the larvae they predate on. This is true regardless of whether the predator is a crustacean, a jellyfish, or a fish.[13]

Dispersal

Fish larvae develop first an ability to swim up and down the water column for short distances. Later they develop an ability to swim horizontally for much longer distances. These swimming developments affect their dispersal.[14]

In 2010, a group of scientists reported that fish larvae can drift on ocean currents and reseed fish stocks at a distant location. This finding demonstrates, for the first time, what scientists have long suspected but have never proven, that fish populations can be connected to distant populations through the process of larval drift.[15]

The fish they chose to investigate was the yellow tang, because when a larva of this fish find a suitable reef it stays in the general area for the rest of its life. Thus, it is only as drifting larvae that the fish can migrate significant distances from where they are born.[16] The tropical yellow tang is much sought after by the aquarium trade. By the late 1990s, their stocks were collapsing, so in an attempt to save them nine marine protected areas (MPAs) were established off the coast of Hawaii. Now, through the process of larval drift, fish from the MPAs are establishing themselves in different locations, and the fishery is recovering.[16] "We've clearly shown that fish larvae that were spawned inside marine reserves can drift with currents and replenish fished areas long distances away," said one of the authors, the marine biologist Mark Hixon. "This is a direct observation, not just a model, that successful marine reserves can sustain fisheries beyond their borders."[16]

Gallery

-

Coregonus maraena eggs about one month after fertilization

-

Salmon eggs in different stages of development.

-

Male goldfish encourage a spawning female and discharge sperm to externally fertilize her eggs

-

Within days, the vulnerable goldfish eggs hatch into larvae, and rapidly develop into fry

-

Atlantic herring eggs, with a newly hatched larva

-

Freshly hatched herring larva in a drop of water compared to a match head.

-

Early stage herring larvae imaged in situ with yolk remains

-

A 2.7mm long larva of the ocean sunfish, Mola mola,

-

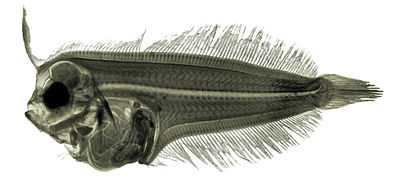

Late stage lanternfish larva

-

A 9mm long late stage scaldfish larva

-

Larvae of a conger eel, 7.6 cm

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spawn. |

- CalCOFI

- Continuous Plankton Recorder

- Crustacean larvae

- Egg case

- Embryo

- LarvalBase - an online database for ichthyoplankton

- Marine larval ecology

- Milt

- Salmon run

- Spawning bed

- Spawning triggers

- Stable Ocean Hypothesis

- Video plankton recorder

Notes

- ↑ Thurman, H. V. (1997). Introductory Oceanography. New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall College. ISBN 0-13-262072-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 What are Ichthyoplankton? Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA. Modified 3 September 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Moser HG and Watson W (2006) "Ichthyoplankton" Pages 269–319. In: Allen LG, Pondella DJ and Horn MH, Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24653-9.

- ↑ Geir Hestmark. "G. O. Sars". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved July 30, 2011. (Google Translate)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Ichthyoplankton sampling methods Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA. Modified 3 September 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kendall Jr AW, Ahlstrom EH and Moser HG (1984) "Early life history stages of fishes and their characters" American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Special publication 1: 11–22.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bax NJ (1998) "The significance and prediction of predation in marine fisheries" ICES Journal of Marine Science, 55: 997–1030.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bailey, K. M., and Houde, E. D. (1989) "Predation on eggs and larvae of marine fishes and the recruitment problem" Advances in Marine Biology, 25: 1–83.

- ↑ Cowan Jr JH, Houde ED and Rose KA (1996) Size-dependent vulnerability of marine fish larvae to predation: an individual-based numerical experiment" ICES J. Mar. Sci., 53(1): 23–37.

- ↑ Purcell, J. E., and Grover, J. J. (1990) "Predation and food limitation as causes of mortality in larval herring at a spawning ground in British Columbia". Marine Ecology Progress Series, 59: 55–61.

- ↑ Johannessen, A. (1980) "Predation on herring (Clupea harengus) eggs and young larvae". ICES C.M. 1980/H:33.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Santander, H.; Alheit, J.; MacCall, A.D.; Alamo, A. (1983) Egg mortality of the Peruvian anchovy (Engraulis ringens) caused by cannibalism and predation by sardines (Sardinops sagax) FAO Fisheries Report, 291(2-3): 443–453. Rome.

- ↑ Paradis AR, Pepin P and Brown JA (1996) "Vulnerability of fish eggs and larvae to predation: review of the influence of the relative size of prey and predator" Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 53:(6) 1226–1235.

- ↑ Cowen RK, CB Paris and A Srinivasan (2006) "Scaling of connectivity in marine populations". Science, 311 (5760): 522–527. doi:10.1126/science.1122039. PDF

- ↑ Christie MR, Tissot BN, Albins MA, Beets3 JP, Jia Y, Ortiz DL, Thompson SE, Hixon MA (2010) Larval Connectivity in an Effective Network of Marine Protected Areas PLoS ONE, 5(12) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015715

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Drifting Fish Larvae Allow Marine Reserves to Rebuild Fisheries ScienceDaily , 26 December 2010.

References

- Ahlstrom, Elbert H. and Moser, H. Geoffrey (1976) "Eggs and larvae of fishes and their role in systematic investigations in fisheries" Revue des Travaux de l'Institut des Pêches Maritimes, 40(3-4): 379–398.

- Balon, Eugene K. (1990) "Epigenesis of an epigeneticist: the development of some alternative concepts on the early ontogeny and evolution of fishes Guelph Ichthyology Reviews, 1: 1–48.

- Blaber, Stephen J. M. (2000) Tropical estuarine fishes: ecology, exploitation and conservation John Wiley and Sons, Page 153–156. ISBN 978-0-632-05655-2.

- Browman, Howard I. and Skiftesvik, Anne Berit (2003) The Big Fish Bang: Proceedings of the 26th Annual Larval Fish Conference Institute of Marine Research. ISBN 978-82-7461-059-0.

- Finn, Roderick Nigel and Kapoor, B. G. (2008) Fish larval physiology Science Publishers.ISBN 9781578083886.

- Cowan, J.H., Jr. and R.F. Shaw (2002) "Recruitment" Chap. 4. pp. 88–111. In: L.A. Fuiman and R.G. Werner (eds.) Fishery Science: The unique contributions of early life stages, John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-632-05661-3.+

- Chambers RC and Trippel EA (1997) Early life history and recruitment in fish population Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-64190-9.

- Houde ED (2010) "Fish Larvae" Page 286–295. In: JH Steele, SA Thorpe and KK Turekian, Marine Biology, Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-096480-5.

- Kendall Jr., Arthur W. (2011) Identification of Eggs and Larvae of Marine Fishes 東海大学出版会, 2011. ISBN 978-4-486-03758-3.

- Miller, Bruce S. and Kendall, Arthur W. (2009) Early life history of marine fishes University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24972-1.

- Miller TJ (2002) "Assemblages, Communities, and Species Interactions" Pages 183–205. In: Lee A. Fuiman and Robert G. Werner, Fishery science: the unique contributions of early life stages, John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-632-05661-3.

- Ichthyoplankton Information System Alaska Fisheries Center, NOAA.

- Early life history section American Fisheries Society.

- Larval Fish Laboratory Colorado State University.

- Recent advances in the study of fish eggs and larvae Sci. Mar., 70S2: 2006.

- Guides and keys to larval and early juvenile fishes Warner College of Natural Resources, Colorado State University.

External links

- Ichthyoplankton Survey Methodology Presentation by Yoshinobu Konishi, SEAFDEC-MFRDMD.

- Salmon Eggs Hatching at the Seymour Hatchery Youtube video.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||