Ibogaine

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 12-Methoxyibogamine | |

| Clinical data | |

| Legal status | Prescription Only (S4) (AU) Legal (CA) Schedule I (US) |

| Routes | oral |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Half-life | 2 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 83-74-9 |

| ATC code | None |

| PubChem | CID 197060 |

| ChemSpider | 170667 |

| UNII | 3S814I130U |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1215855 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C20H26N2O |

| Mol. mass | 310.433 g/mol |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| Physical data | |

| Melt. point | 152–153 °C (306–307 °F) |

| | |

Ibogaine is a naturally occurring psychoactive substance found in plants in the Apocynaceae family such as Tabernanthe iboga, Voacanga africana and Tabernaemontana undulata. A psychedelic with dissociative properties, the substance is banned in some countries; in other countries it is used by proponents of psychedelic therapy to treat addiction to methadone, heroin, alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine, anabolic steroids, and other drugs. Derivatives of ibogaine that lack the substance's psychedelic properties are under development.[1]

Ibogaine-containing preparations are used for medicinal and ritual purposes within African spiritual traditions of the Bwiti, who claim to have learned it from the Pygmy peoples. Although it was first commonly advertised as having anti-addictive properties in 1962 by Howard Lotsof, its western use predates that by at least a century. In France it was marketed as Lambarène, a medical drug used as a stimulant. Additionally, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) studied the effects of ibogaine in the 1950s.[2]

Ibogaine is an indole alkaloid that is obtained either by extraction from the iboga plant or by semi-synthesis from the precursor compound voacangine,[3][4] another plant alkaloid. A full organic synthesis of ibogaine has been achieved. The synthesis process is too expensive and challenging to be used to produce a commercially significant yield. The synthesis was published with U.S. Patent 2,813,873 in 1956.[5] The free base and the HBr salt have both been characterised by X-ray crystallography.[6][7]

While ibogaine's prohibition in several countries has slowed scientific research into its anti-addictive properties, the use of ibogaine for drug treatment has grown in the form of a large worldwide medical subculture.[8] Ibogaine is also used to facilitate psychological introspection and spiritual exploration.

History

It is uncertain exactly how long iboga has been used in African spiritual practice, but its activity was first observed by French and Belgian explorers in the 19th century. The first botanical description of the Tabernanthe iboga plant was made in 1889. Ibogaine was first isolated from T. iboga in 1901 by Dybowski and Landrin[9] and independently by Haller and Heckel in the same year using T. iboga samples from Gabon. The total synthesis of ibogaine was accomplished by G. Büchi in 1966.[10] Since then, several further totally synthetic routes have been developed.[11]

Since the 1930s, ibogaine was sold in France in 8 mg tablets in the form of Lambarène, an extract of the Tabernanthe manii plant. Lambarène was advertised as a mental and physical stimulant and was "...indicated in cases of depression, asthenia, in convalescence, infectious disease, [and] greater than normal physical or mental efforts by healthy individuals". The drug enjoyed some popularity among post World War II athletes, but was eventually removed from the market, when the sale of ibogaine-containing products was prohibited in 1966.[12] In the end of 1960's World Health Assembly classifies ibogaine as a “substance likely to cause dependency or endanger human health,” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) assigns ibogaine Schedule I classification, The International Olympic Committee banned ibogaine as a potential doping agent and sales of Lambarène ceased.[13]

In the early 1960s, anecdotal reports appeared concerning ibogaine's effects.[14] The use of ibogaine in treating substance use disorders in human subjects was first observed by Howard Lotsof in 1962, for which he was later awarded U.S. Patent 4,499,096 in 1985.

Ibogaine was placed in US Schedule 1 in 1967 as part of the US government's strong response to the upswing in popularity of psychedelic substances, though iboga itself was scarcely known at the time. Ibogaine's ability to attenuate opioid withdrawal confirmed in the rat was first published by Dzoljic et al. (1988).[15] Ibogaine's use in diminishing morphine self-administration in preclinical studies was shown by Glick et al. (1991)[16] and ibogaine's capacity to reduce cocaine self-administration in the rat was shown by Cappendijk et al. in 1993.[17] Animal model support for ibogaine claims to treat alcohol dependence were established by Rezvani in 1995.[18]

The name "Indra extract", in strict terms, refers to 44 kg of an iboga extract manufactured by an unnamed European industrial manufacturer in 1981. This stock was later purchased by Carl Waltenburg, who distributed it under the name "Indra extract". Waltenburg used this extract to treat heroin addicts in Christiania, Denmark, a squatter village where heroin addiction was widespread in 1982.[19] Indra extract was offered for sale over the Internet until 2006, when the Indra web presence disappeared. It is unclear whether the extracts currently sold as "Indra extract" are actually from Waltenburg's original stock, or whether any of that stock is even viable or in existence. Ibogaine and related indole compounds are susceptible to oxidation when exposed to oxygen.[20][21]

An ibogaine research project was funded by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse in the 1990s. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) abandoned efforts to continue this project into clinical studies in 1995.[22] Data demonstrating ibogaine's efficacy in attenuating opioid withdrawal in drug-dependent human subjects was published by Alper et al. (1999)[23] and Mash et al. (2000).[24]

Synthesis

One recent total synthesis[25] of ibogaine and related drugs starts with 2-iodo-4-methoxyaniline which is reacted with triethyl((4-(triethylsilyl)but-3-yn-1-yl)oxy)silane using palladium acetate in DMF to form 2-(triethylsilyl)-3-(2-((triethylsilyl)oxy)ethyl)-1H-indole. This is converted using N-iodosuccinamide and then fluoride to form 2-(2-iodo-1H-indol-3-yl)ethanol. This is treated with iodine, triphenyl phosphine and imidazole to form 2-iodo-3-(2-iodoethyl)-1H-indole. Then using 7-ethyl-2-azabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-5-ene and cesium carbonate in acetonitrile the ibogaine precursor 7-ethyl-2-(2-(2-iodo-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)-2-azabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-5-ene is obtained. Using palladium acetate in DMF the ibogaine is obtained. If the exo ethyl group on the 2-azabicyclo[2.2.2]octane system in ibogaine is replaced with an endo ethyl then epiibogaine is formed.

Side effects and safety

One of the first noticeable effects of large-dose ibogaine ingestion is ataxia, a difficulty in coordinating muscle motion which makes standing and walking difficult without assistance. Xerostomia (dry mouth), nausea, and vomiting may follow. These symptoms may be long in duration, ranging from 4 to 24 hours in some cases. Ibogaine is sometimes administered by enema to help the subject avoid vomiting up the dose. Psychiatric medications are strongly contraindicated in ibogaine therapy due to adverse interactions. Some studies also suggest the possibility of adverse interaction with heart conditions. In one study of canine subjects, ibogaine was observed to increase sinus arrhythmia (the normal change in heart rate during respiration).[26] It was proposed that there is a risk of QT-interval prolongation following ibogaine administration.[27] This risk was further demonstrated by a case reported in the New England Journal of Medicine documenting prolonged QT interval and ventricular tachycardia after initial use.[28]

Fatalities following ibogaine ingestion are documented in the medical literature.[29] Lethal respiratory and cardiac effects are associated with use.[30] Also, because ibogaine is one of the many drugs that are partly metabolized by the cytochrome P450 complex, caution must be exercised to avoid foods or drugs that inhibit CP450, in particular foodstuffs containing bergamottin or bergamot oil, common ones being grapefruit juice.[31]

Therapeutic uses

Treatment for various addictions

The most-studied therapeutic effect of ibogaine is the reduction or elimination of addiction to opioids. An integral effect is the alleviation of symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Research also suggests that ibogaine may be useful in treating dependence on other substances such as alcohol, methamphetamine, and nicotine and may affect compulsive behavioral patterns not involving substance abuse or chemical dependence. Researchers note that there remains a "need for systematic investigation in a conventional clinical research setting."[14]

Many users of ibogaine report experiencing visual phenomena during a waking dream state, such as instructive replays of life events that led to their addiction, while others report therapeutic shamanic visions that help them conquer the fears and negative emotions that might drive their addiction. It is proposed that intensive counseling, therapy and aftercare during the interruption period following treatment is of significant value. Some individuals require a second or third treatment session with ibogaine over the course of the next 12 to 18 months. A minority of individuals relapse completely into opiate addiction within days or weeks. A comprehensive article (Lotsof 1995) on the subject of ibogaine therapy detailing the procedure, effects and aftereffects is found in "Ibogaine in the Treatment of Chemical Dependence Disorders: Clinical Perspectives".[32] Ibogaine has also been reported in multiple small-study cohorts to reduce cravings for methamphetamine.[33]

There is also evidence that this type of treatment works with LSD, which has been shown to have a therapeutic effect on alcoholism. Both ibogaine and LSD appear to be effective for encouraging introspection and giving the user occasion to reflect on the sources of their addiction, while also producing an intense, transformative experience that can put established patterns of behaviour into perspective;[34] ibogaine has the added benefit of preventing withdrawal effects.[14]

As ibogaine has been banned in the United States since the 1960s, treatments using ibogaine are considered illegal.[35] Treatment centers are located in various countries where ibogaine is either allowed through regulation or not regulated such as Mexico and Canada.[35][36] Costa Rica also has treatment centers, most notably one run by Lex Kogan who is considered the leading proponent of ibogaine.[37]

Chronic pain management

In 1957, Jurg Schneider, a pharmacologist at CIBA, now Novartis, found that ibogaine potentiates morphine analgesia.[38] Further research was abandoned, and no additional data was ever published by Ciba researchers on ibogaine–opioid interactions. Almost 50 years later, Patrick Kroupa and Hattie Wells released the first treatment protocol for concomitant administration of ibogaine with opioids in human subjects, indicating ibogaine reduced tolerance to opioid drugs. They published their research in the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies Journal demonstrating that administration of low-"maintenance" doses of ibogaine HCl with opioids decreases tolerance. It should be noted however, that the potentiation action of ibogaine may make this a very risky procedure.[39]

Psychotherapy

Ibogaine has been used as an adjunct to psychotherapy by Claudio Naranjo, documented in his book The Healing Journey.[40] He was awarded CA 939266 in 1974.

Formulations

In Bwiti religious ceremonies, the root bark is pulverized and swallowed in large amounts to produce intense psychoactive effects. In Africa, iboga root bark is sometimes chewed, releasing small amounts of ibogaine to produce a stimulant effect. Ibogaine is also available in a total alkaloid extract of the Tabernanthe iboga plant, which also contains all the other iboga alkaloids and thus has only about half the potency by weight as standardized ibogaine hydrochloride.[41]

Currently, pure crystalline ibogaine hydrochloride is the most standardized formulation. It is typically produced by semi-synthesis from voacangine in commercial laboratories. Ibogaine has two separate chiral centers, meaning that there are four different stereoisomers of ibogaine. These four isomers are difficult to resolve.[42]

A synthetic derivative of ibogaine, 18-methoxycoronaridine (18-MC), is a selective α3β4 antagonist that was developed collaboratively by the neurologist Stanley D. Glick (Albany) and the chemist Martin E. Kuehne (Vermont).[43] This discovery was stimulated by earlier studies on other naturally occurring analogues of ibogaine such as coronaridine and voacangine that showed these compounds also have anti-addictive properties.[44][45]

Psychoactive effects

Ibogaine is a psychedelic.[46] The experience of Ibogaine is broken down in two phases; the visionary phase comes first, then the introspection phase.[47]

The visionary phase has been described as oneirogenic and lasts for 4 to 6 hours. The second phase, the introspection phase, is responsible for the psychotherapeutic effects of ibogaine. It can allow people to conquer their fears and negative emotions.[47]

Ibogaine has been referred to as an oneirogen, referring to the dreamlike nature of its psychedelic effects. Ibogaine catalyzes an altered state of consciousness reminiscent of dreaming while fully conscious and aware so that memories, life experiences, and issues of trauma can be processed.[47]

Pharmacology

| Receptor | Ibogaine | Noribogaine |

|---|---|---|

| κ-opioid | 2.2 | 0.61 |

| μ-opioid | 2.0 | 0.68 |

| δ-opioid | >10 | 5.2 |

| NMDA | 3.1 | 15 |

| 5-HT2A | 16 | >100 |

| 5-HT2C | >10 | >10 |

| 5-HT3 | 2.6 | >100 |

| σ1 | 2.5 | 11 |

| σ2 | 0.4 | 19 |

Ibogaine affects many different neurotransmitter systems simultaneously.[49][50] Because of its fairly low potency at any of its target sites, ibogaine is used in doses anywhere from 5 mg/kg of body weight for a minor effect to 30 mg/kg in the cases of strong polysubstance addiction. It is unknown whether doses greater than 30 mg/kg in humans produce effects that are therapeutically beneficial, medically risky, or simply prolonged in duration. In animal neurotoxicity studies, there was no observable neurotoxicity of ibogaine at 25 mg/kg, but at 50 mg/kg, one-third of the rats had developed patches of neurodegeneration, and at doses of 75 mg/kg or above, all rats showed a characteristic pattern of degeneration of Purkinje neurons, mainly in the cerebellum.[51] While caution should be exercised when extrapolating animal studies to humans, these results suggest that neurotoxicity of ibogaine is likely to be minimal when ibogaine is used in the 10–20 mg/kg range typical of drug addiction interruption treatment regimes, and indeed death from the other pharmacological actions of the alkaloids is likely to occur by the time the dose is high enough to produce consistent neurotoxic changes.[21]

Pharmacodynamics

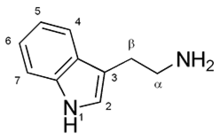

Ibogaine is a tryptamine. Because of the ibogaine molecule's tryptamine core, ibogaine acts as an agonist (binds to the receptor and triggers a response) for the 5-HT2A receptor.[52] However what makes ibogaine's pharmacodynamic properties and subjective experience unique from that of other psychedelic tryptamines and serotonergic psychedelics is that it also acts as an antagonist (blocks agonists' effects) of the NMDA receptor set and an agonist for the κ-opioid receptor set.[53]

Metabolites

Ibogaine is metabolized in the human body by cytochrome P450 2D6 into noribogaine (12-hydroxyibogamine). Noribogaine is most potent as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. It acts as a moderate κ-opioid receptor antagonist and weak µ-opioid receptor full agonist and therefore, also has an aspect of an opiate replacement similar to compounds like methadone. It is possible that this action of noribogaine at the kappa opioid receptor may indeed contribute significantly to the psychoactive effects attributed to ibogaine ingestion; Salvia divinorum, another plant recognized for its strong hallucinogenic properties, contains the chemical salvinorin A which is a highly selective kappa opioid agonist. Both ibogaine and noribogaine have a plasma half-life of around two hours in the rat,[54] although the half-life of noribogaine is slightly longer than that of the parent compound. It is proposed that ibogaine is deposited in fat and metabolized into noribogaine as it is released.[55] Noribogaine shows higher plasma levels than ibogaine and may accordingly be detected for longer periods of time than ibogaine. Noribogaine is also more potent than ibogaine in rat drug discrimination assays when tested for the subjective effects of ibogaine.[56]

Legal status

As of 2009, ibogaine is unregulated in Canada[57][58] and Mexico.[1]

Ibogaine is schedule I in Sweden.[59]

Ibogaine is regulated by the United States Controlled Substances Act, as a Schedule I-controlled substance.[60]

Ibogaine is unregulated in Norway.[61]

Ibogaine in the media

Documentary films about ibogaine therapy

- Detox or Die (2004)

- Directed by David Graham Scott.[62] David Graham Scott begins videotaping his heroin-addicted friends. Before long, he himself is addicted to the drug. He eventually turns the camera to himself and his family. After 12 years of debilitating, painful dependence on methadone, Scott turns to ibogaine. Filmed in Scotland and England, and broadcast on BBC One as the third instalment in the documentary series One Life.[63]

- Ibogaine

- Rite of Passage (2004)

- Directed by Ben Deloenen.[64] Cy a 34 year old heroin addict undergoes ibogaine treatment with Dr Martin Polanco at the Ibogaine Association, a clinic in Rosarito Mexico. Deloenen interviews people formerly addicted to heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine, who share their perspectives about ibogaine treatment. In Gabon, a Babongo woman receives iboga root for her depressive malaise. Deloenen visually contrasts this Western, clinical use of ibogaine with the Bwiti use of iboga root, but emphasizes the Western context.

- Facing the Habit (2007)

- Directed by Magnolia Martin.[65] Martin's subject is a former millionaire and stockbroker who travels to Mexico for ibogaine treatment for heroin addiction.

- Tripping in Amsterdam (2008)

- In this short film directed by Jan Bednarz, Simon "Swany" Wan visits Sara Glatt's iboga treatment center in Amsterdam.[66] Current TV broadcast the documentary in 2008, as part of their "Quarter-life Crisis" programming roster.

- I'm Dangerous with Love (2009)

- Directed by Michel Negroponte.[67] Negroponte examines Dimitri Mugianis's long, clandestine career of treating heroin addicts with ibogaine.

- "Hallucinogens" (2012)

- In one of five segments from this episode of Drugs, Inc. on National Geographic Channel, a former heroin user treats addicts with ibogaine in Canada. He himself used ibogaine to stop his abuse of narcotics.[68]

- "Addiction" (2013)

- This episode of the HBO documentary series Vice[69] devotes a segment to the use of ibogaine to interrupt heroin addiction.

Print media

While in Wisconsin covering the primary election for the United States presidential election of 1972, gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson submitted a satirical article to his editor at Rolling Stone accusing presidential nominee Edmund Muskie of being addicted to ibogaine. When Rolling Stone published the piece, many readers, and even other journalists, did not realize that Thompson's assertion was facetious. The claim was completely unfounded, and Thompson was surprised that anyone believed it.[70]

After the election, Thompson republished the article (slightly modified) in his article anthology Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72 (1973).[71] Muskie was not elected to the Presidency.

American author Daniel Pinchbeck wrote about his own experience of ibogaine in his book Breaking Open the Head (2002),[72] and in a 2003 article for The Guardian titled "Ten years of therapy in one night".[73]

Television drama

Ibogaine factors into the stories of these episodes from television drama series:

- "Via Negativa". The X-Files. Season 8. Episode 7. 17 December 2000. Fox Broadcasting Company.[74]

- "Getting Off". CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. Season 4. Episode 16. 26 February 2004. CBS.[75]

- "Users". Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. Season 11. Episode 7. 4 November 2009. NBC.[76]

- "Echoes". Nikita. Season 1. Episode 16. 24 February 2011. The CW Television Network.[77]

- "One Last Time". Homeland (TV series). Season 3. Episode 9. 24 November 2013. Showtime.[78]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hamilton, Keegan (2010-11-17). "Ibogaine: Can it Cure Addiction Without the Hallucinogenic Trip?". Village Voice.

- ↑ Alper, Kenneth Robert (2001). "Chapter 1. Ibogaine: A review". The Alkaloids 56 (Academic Press). Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ↑ Chris Jenks: Extracting Ibogaine Chris Jenks tells about the findings of his Extraction Studies.

- ↑ Iboga Extraction Manual Compiled 2009 by Dr. Chris Jenks.

- ↑ US patent 2813873, Morrice-Marie Janot & Robert Goutarel, "Derivatives of the ibogaine alkaloids", issued 1957-11-19, assigned to Les Laboratoires Gobey

- ↑ Soriano-García, M.; Walls, F.; Rodríguez, A.; López Celis, I. (1988). "Crystal and molecular structure of ibogamine: An alkaloid from Stemmadenia galeottiana". Journal of Crystallographic and Spectroscopic Research 18 (2): 197. doi:10.1007/BF01181911.

- ↑ Arai, G.; Coppola, J.; Jeffrey, G. A. (1960). "The structure of ibogaine". Acta Crystallographica 13 (7): 553. doi:10.1107/S0365110X60001369.

- ↑ Alper, K.R.; Lotsof, H.S. and Kaplan, C.D. (2008). "The Ibogaine Medical Subculture". J. Ethnopharmacology 115 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.034. PMID 18029124. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Dybowski, J. and Landrin, E. (1901). "PLANT CHEMISTRY. Concerning Iboga, its excitement-producing properties, its composition, and the new alkaloid it contains, ibogaine". C. R. Acad. Sci. 133: 748.

- ↑ Büchi, G.; Coffen, D.L.; Kocsis, Karoly; Sonnet, P.E. and Ziegler, Frederick E. (1966). "The Total Synthesis of Iboga Alkaloids". J. Am. Chem. Soc. (PDF) 88 (13): 3099–3109. doi:10.1021/ja00965a039.

- ↑ Frauenfelder, Christine (1999). Doctoral Thesis (Thesis). p. 24. Archived from the original on 2012-08-17.

- ↑ Ibogaine: A Novel Anti-Addictive Compound – A Comprehensive Literature Review Jonathan Freedlander, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Journal of Drug Education and Awareness, 2003; 1:79–98.

- ↑ Ibogaine – Scientific Literature Overview The International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research & Service (ICEERS) 2012

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Alper, K.R.; Lotsof, H.S.; Frenken, G.M.; Luciano, D.J. and Bastiaans, J. (1999). "Treatment of Acute Opioid Withdrawal with Ibogaine". The American Journal on Addictions 8 (3): 234–42. doi:10.1080/105504999305848. PMID 10506904. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ Dzoljic ED, Kaplan CD, Dzoljic MR (1988). "Effect of ibogaine on naloxone-precipitated withdrawal syndrome in chronic morphine-dependent rats". Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 294: 64–70. PMID 3233054.

- ↑ Glick SD, Rossman K, Steindorf S, Maisonneuve IM, Carlson JN (1991). "Effects and aftereffects of ibogaine on morphine self-administration in rats". Eur. J. Pharmacol 195 (3): 341–345. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(91)90474-5. PMID 1868880.

- ↑ Cappendijk SLT, Dzoljic MR (1993). "Inhibitory effects of ibogaine on cocaine self-administration in rats". European Journal of Pharmacology 241 (2–3): 261–265. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(93)90212-Z. PMID 8243561.

- ↑ Rezvani A, Overstreet D, Lee Y (1995). "Attenuation of alcohol intake by ibogaine in three strains of alcohol preferring rats". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behaviour 52 (3): 615–20. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(95)00152-M. PMID 8545483.

- ↑ Alper, Kenneth R.; Beal, Dana and Kaplan, Charles D. A Contemporary History of Ibogaine in the United States and Europe. "Ibogaine: Proceedings of the First International Conference". The Alkaloids 56. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Taylor WI (1965). "The Iboga and Voacanga Alkaloids". The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Physiology. pp. 203, 207–208.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kontrimaviciūte V; Mathieu O; Mathieu-Daudé JC; Vainauskas, P; Casper, T; Baccino, E; Bressolle, FM (September 2006). "Distribution of ibogaine and noribogaine in a man following a poisoning involving root bark of the Tabernanthe iboga shrub". J Anal Toxicol 30 (7): 434–40. doi:10.1093/jat/30.7.434. PMID 16959135.

- ↑ Doblin, Rick. A Non-Profit Approach to Developing Ibogaine into an FDA-Approved Medication (ppt). Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ↑ Alper KR, Lotsof HS, Frenken GM, Luciano DJ, Bastiaans J (1999). "Treatment of acute opioid withdrawal with ibogaine" (PDF). Am J Addict 8 (3): 234–42. doi:10.1080/105504999305848. PMID 10506904.

- ↑ Mash DC; Kovera CA; Pablo J; Tyndale, Rachel F.; Ervin, Frank D.; Williams, Izben C.; Singleton, Edward G.; Mayor, Manny (September 2000). "Ibogaine: complex pharmacokinetics, concerns for safety, and preliminary efficacy measures". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 914: 394–401. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05213.x. PMID 11085338.

- ↑ Jana, G. K.; Sinha, S. (2012). "Total synthesis of ibogaine, epiibogaine and their analogues". Tetrahedron 68 (35): 7155. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2012.06.027.

- ↑ Gershon, S; Lang, WJ (1962). "A psycho-pharmacological study of some indole alkaloids". Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de therapie 135: 31–56. PMID 13898069.

- ↑ Maas U, Strubelt S (2006). "Fatalities after taking ibogaine in addiction treatment could be related to sudden cardiac death caused by autonomic dysfunction". Med. Hypotheses 67 (4): 960–4. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.050. PMID 16698188.

- ↑ Hoelen DW, Spiering W, Valk GD (January 2009). "Long-QT syndrome induced by the antiaddiction drug ibogaine". N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (3): 308–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0804248. PMID 19144953.

- ↑ Alper, K. R.; Stajić, M.; Gill, J. R. (2012). "Fatalities Temporally Associated with the Ingestion of Ibogaine". Journal of Forensic Sciences 57 (2): 398–412. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.02008.x. PMID 22268458.

- ↑ Paling, F. P.; Andrews, L. M.; Valk, G. D.; Blom, H. J. (2012). "Life-threatening complications of ibogaine: Three case reports". The Netherlands journal of medicine 70 (9): 422–424. PMID 23123541.

- ↑ "Grapefruit juice: Beware of dangerous medication interactions". Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- ↑ Lotsof, H.S. (1995). Ibogaine in the Treatment of Chemical Dependence Disorders: Clinical Perspectives 3. MAPS Bulletin. pp. 19–26.

- ↑ Giannini, A. James (1997). Drugs of Abuse (2 ed.). Practice Management Information Corporation. ISBN 1-57066-053-0.

- ↑ Ludwig, A.; Levine, J.; Stark, L.; Lazar, R. (1969). "A clinical study of LSD treatment in alcoholism". The American journal of psychiatry 126 (1): 59–69. PMID 5798383.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Hamilton, Keegan (13 November 2013). "The Shaman Will See You Now". The Village Voice (New York). Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Powerful Drug Could Help People Kick Addictions". CBS Local (New York). 27 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Costa Rican Center a Leader in Alternative Ibogaine Therapy". Treatment Magazine. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ US patent 2817623, Jurg Schneider, "Tabernanthine, Ibogaine Containing Analgesic Compositions.", issued 1957-12-24, assigned to Ciba Pharmaceuticals Inc.

- ↑ Kroupa, Patrick K. and Wells, Hattie (2005). Ibogaine in the 21st Century (PDF) XV (1). Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. pp. 21–25.

- ↑ Naranjo, Claudio (1973). "V, Ibogaine: Fantasy and Reality". The healing journey: new approaches to consciousness. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 197–231. ISBN 0-394-48826-1. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Jenks, C. (2002). "Extraction Studies ofTabernanthe IbogaandVoacanga Africana". Natural Product Letters 16 (1): 71–76. doi:10.1080/1057563029001/4881. PMID 11942686.

- ↑ Shulgin, Alexander; Shulgin, Ann (1997). TiHKAL. p. 487.

- ↑ Pace CJ; Glick SD; Maisonneuve IM; He, Li-Wen; Jokiel, Patrick A.; Kuehne, Martin E.; Fleck, Mark W. (2004). "Novel iboga alkaloid congeners block nicotinic receptors and reduce drug self-administration". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 492 (2–3): 159–67. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.062. PMID 15178360.

- ↑ Glick SD; Kuehne ME; Raucci J; Wilson, T.E.; Larson, D.; Keller, R.W.; Carlson, J.N. (1994). "Effects of iboga alkaloids on morphine and cocaine self-administration in rats: relationship to tremorigenic effects and to effects on dopamine release in nucleus accumbens and striatum". Brain Res. 657 (1–2): 14–22. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(94)90948-2. PMID 7820611.

- ↑ Tsing Hua (2006-01-28). Antiaddictive indole alkaloids in Ervatamia yunnanensis and their bioactivity. Academic Journal of Second Military Medical University. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Alper, Kenneth R.; Beal, Dana; Kaplan, Charles D. (2001). A CONTEMPORARY HISTORY OF IBOGAINE IN THE UNITED STATES AND EUROPE. Academic Press. p. 256.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Obembe, Samuel (2012). Practical Skills and Clinical Management of Alcoholism & Drug Addiction. Elsevier. p. 88. ISBN 9780123985187.

- ↑ Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, Szumlinski KK (2001). "Mechanisms of action of ibogaine: relevance to putative therapeutic effects and development of a safer iboga alkaloid congener". Alkaloids Chem Biol. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology 56: 39–53. doi:10.1016/S0099-9598(01)56006-X. ISBN 9780124695566. PMID 11705115.

- ↑ Popik, P. and Skolnick, P. (1998). 3. In G.A. Cordell. "Pharmacology of Ibogaine and Ibogaine-Related Alkaloids". The Alkaloids (Academic Press) 52: 197–231.

- ↑ Alper, Kenneth R. and Glick, Stanley D. (2001). "Ibogaine: A Review" (PDF). The alkaloids: chemistry and biology 56. San Diego: Academic. pp. 1–38. ISBN 0-12-469556-6.

- ↑ Xu Z, Chang LW, Slikker W, Ali SF, Rountree RL, Scallet AC (2000). "A dose-response study of ibogaine-induced neuropathology in the rat cerebellum". Toxicol. Sci. 57 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1093/toxsci/57.1.95. PMID 10966515.

- ↑ Berger ML, Palangsuntikul R, Rebernik P, Wolschann P, Berner H. (2012). "Screening of 64 Tryptamines at NMDA, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT2A Receptors: A Comparative Binding and Modeling Study". Current medicinal chemistry (Current Medicinal Chemistry) 19 (18): 3044–57. doi:10.2174/092986712800672058. PMID 22519402.

- ↑ Glick, S. D.; Maisonneuve, I. M. (1998). "Mechanisms of Antiaddictive Actions of Ibogainea". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 844: 214–226. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08237.x. PMID 9668680.

- ↑ Baumann MH, Rothman RB, Pablo JP, Mash DC (2001). "In vivo neurobiological effects of ibogaine and its O-desmethyl metabolite, 12-hydroxyibogamine (noribogaine), in rats". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 297 (2): 531–9. PMID 11303040.

- ↑ Hough LB, Bagal AA, Glick SD (2000). "Pharmacokinetic characterization of the indole alkaloid ibogaine in rats". Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 22 (2): 77–81. doi:10.1358/mf.2000.22.2.796066. PMID 10849889.

- ↑ Zubaran C, Shoaib M, Stolerman IP, Pablo J, Mash DC (July 1999). "Noribogaine generalization to the ibogaine stimulus: correlation with noribogaine concentration in rat brain". Neuropsychopharmacology 21 (1): 119–26. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00003-2. PMID 10379526.

- ↑ Johnson, Gail (2003-01-02). "Ibogaine: A one-way trip to sobriety, pot head says". straight.com. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Canadian Department of Justice. 1996. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/upload/lvfs/LVFS%201997-12.pdf

- ↑ Scheduling Actions Controlled Substances Regulated Chemicals. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ http://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2013-02-14-199

- ↑ Detox or Die (2004) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ One Life at the British Film Institute's Film and TV Database

- ↑ Ibogaine: Rite of Passage (2004) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Facing the Habit (2007) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Tripping in Amsterdam". Current.com. Current TV. 23 June 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Dangerous with Love (2009) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Hallucinogens" at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Addiction" at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Gibney, Alex (2008). Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson (Motion picture). OCLC 259718859.

- ↑ Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. Straight Arrow Books. 1973. pp. 150–54. ISBN 978-0-87932-053-9. OCLC 636410.

- ↑ Pinchbeck, Daniel (2002). Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journey into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism. Broadway Books. ISBN 9780767907422. OCLC 50601753.

- ↑ Pinchbeck, Daniel (19 September 2003). "Ten years of therapy in one night". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media). Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Via Negativa" at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Getting Off" at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Users" at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Echoes" at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Horse and Wagon" at the Internet Movie Database

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||

| |||||