Iberian Peninsula

| |

|---|---|

Satellite image of the Iberian Peninsula. | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Southern & Western Europe |

| Coordinates | 40°N 4°W / 40°N 4°W |

| Area | 581,471.1 km2 (224,507.2 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,478 m (11,411 ft) |

| Highest point | Mulhacén |

| Sovereign states and dependent territories | |

| Largest city | Andorra la Vella |

| Largest city | Gibraltar |

| Largest city | Lisbon |

| Largest city | Madrid |

| Largest city | Font-Romeu-Odeillo-Via |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Iberian |

| Population | 54 million |

The Iberian Peninsula (Asturian, Galician, Leonese, Mirandese, Portuguese, and Spanish: Península Ibérica, Catalan: Península Ibèrica, Aragonese and Occitan: Peninsula Iberica, French: Péninsule Ibérique, Basque: Iberiar Penintsula), commonly called Iberia, is a peninsula located in the extreme south-west of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal, Andorra, and part of France, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. It is the westernmost of the three major southern European peninsulas—the Iberian, Italian, and Balkan peninsulas. It is bordered on the south-east and east by the Mediterranean Sea, and on the north, west, and south-west by the Atlantic Ocean. The Pyrenees form the north-east edge of the peninsula, separating it from the rest of Europe. In the south, it approaches the northern coast of Africa. It is the second-largest peninsula in Europe, with an area of approximately 582,000 km2 (225,000 sq mi).

Name

Greek name

The English word Iberia was adapted from the use of the Ancient Greek word Ιβηρία (Ibēría) by the Greek geographers under the Roman Empire to refer to what is known today in English as the Iberian Peninsula.[5] At that time the name did not describe a single political entity or a distinct population of people.[6] Strabo's Iberia was delineated from Keltikē by the Pyrenees and included the entire land mass south-west (he named it "west") of there.

The ancient Greeks discovered the Iberian peninsula by voyaging westward. Hecataeus of Miletus was the first known to use the term around 500 BC.[7] Herodotus of Halicarnassus says of the Phocaeans that "it was they who made the Greeks acquainted with ... Iberia."[8] According to Strabo[9] prior historians used Iberia to mean the country "this side of the Ἶβηρος (Ibēros)" as far north as the river Rhône in France but currently they set the Pyrenees as the limit. Polybius respects that limit[10] but identifies Iberia as the Mediterranean side as far south as Gibraltar, with the Atlantic side having no name. Elsewhere[11] he says that Saguntum is "on the seaward foot of the range of hills connecting Iberia and Celtiberia."

Strabo[12] refers to the Carretanians as people "of the Iberian stock" living in the Pyrenees, who are to be distinguished from either Celts or Celtiberians.

Roman names

When the Romans encountered the Greek geographers they used Iberia poetically and spoke of the Iberi.[13] First mention was in 200 BC by the poet Quintus Ennius. The Romans had already had independent experience with the peoples on the peninsula during the long conflict with Carthage. The Roman geographers and other prose writers from the time of the late Roman Republic called the entire peninsula Hispania.

As they became politically interested in the former territories of Carthage, the Romans came to use Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior for 'near' and 'far Spain'. Even at that time large sections of it were Lusitania (Portugal south of Douro river and Extremadura in western Spain), Gallaecia (Northern Portugal and Galicia in Spain), Celtiberia (central Spain), Baetica (Andalusia), Cantabria (North-West Spain) and the Vascones (Basques). Strabo says[9] that the Romans use Hispania and Iberia synonymously, and distance them as near and far. He was living in a time when the peninsula was divided into Roman provinces, of which Baetia was supervised by the Senate, whereas the others were governed on behalf of the Emperor. Whatever language may have been spoken on the peninsula soon gave way to Latin, except for Basque, protected by the Pyrenees.

Etymology

The Iberian Peninsula has always been associated with the Ebro River, Ibēros in ancient Greek and Ibērus or Hibērus in Latin. The association was so well known it was hardly necessary to state; for example, Ibēria was the country "this side of the Ibērus" in Strabo. Pliny goes so far as to assert that the Greeks had called "the whole of Spain" Hiberia because of the Hiberus River.[14] The river appears in the Ebro Treaty of 226 BC between Rome and Carthage, setting the limit of Carthaginian interest at the Ebro. The fullest description of the treaty, stated in Appian,[15] uses Ibērus. With reference to this border, Polybius[16] states that the "native name" is Ibēr, apparently the original word, stripped of its Greek or Latin -os or -us termination.

The early range of these natives, stated by the geographers and historians to be from southern Spain to southern France along the Mediterranean coast, is marked by instances of a readable script expressing a yet unknown language, dubbed "Iberian." Whether this was the native name or was given to them by the Greeks for their residence on the Ebro remains unknown. Credence in Polybius imposes certain limitations on etymologizing: if the language remains unknown, the meanings of the words, including Iber, must remain unknown also. In modern Basque the word ibar means 'valley' or 'watered meadow', while ibai means 'river', but there is no proof relating the etymology of the Ebro River with these Basque names.

Prehistory

Palaeolithic

The Iberian Peninsula has been inhabited for at least 1,000,000 years as remains found in the sites at Atapuerca demonstrate. Among these sites is the cave of Gran Dolina, where six hominin skeletons, dated between 780,000 and one million years ago, were found in 1994. Experts have debated whether these skeletons belong to the species Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or a new species called Homo antecessor.

Around 200,000 BC, during the Lower Paleolithic period, Neanderthals first entered the Iberian Peninsula. Around 70,000 BC, during the Middle Paleolithic period, the last ice age began and the Neanderthal Mousterian culture was established. Around 35,000 BC, during the Upper Paleolithic, the Neanderthal Châtelperronian cultural period began. Emanating from Southern France this culture extended into the north of the peninsula. It continued to exist until around 28,000 BC when Neanderthal man faced extinction.

At about the 40th millennium BC Modern Humans entered the Iberian peninsula, coming from Southern France.[citation needed] Here, this genetically homogeneous population (characterized by the M173 mutation in the Y-chromosome), developed the M343 mutation, giving rise to the R1b Haplogroup, still the most common in modern Portuguese and Spanish males. On the Iberian peninsula, Modern Humans developed a series of different cultures, such as the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian cultures, some of them characterized by complex forms of Paleolithic art.

Neolithic

During the Neolithic expansion, various megalithic cultures developed in the Iberian Peninsula. An open seas navigation culture from the east Mediterranean, called the Cardium culture, also extended its influence to the eastern coasts of the peninsula, possibly as early as the 5th millennium BC. These people may have had some relation to the subsequent development of the Iberian civilization.

Chalcolithic

In the Chalcolithic or Copper Age (c. 3000 BC) a series of complex cultures developed, which would give rise to the peninsula's first civilizations and to extensive exchange networks reaching to the Baltic, the Middle East and North Africa. At around 2800 – 2700 BC the Bell Beaker culture producing the Maritime Bell Beaker probably originated in the vibrant copper—using communities of the Tagus estuary in Portugal around 2800 – 2700 BC and spread from there to many parts of western Europe.[17]

Bronze Age

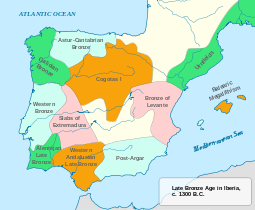

Bronze Age cultures developed beginning c.1800 BC, when the civilization of Los Millares was followed by that of El Argar. From this centre, bronze technology spread to other areas, such as those of the Bronze of Levante, South-Western Iberian Bronze and Cogotas I.

In the Late Bronze Age the urban civilisation of Tartessos developed in the area of modern western Andalusia, characterized by Phoenician influence and using the Tartessian script for its Tartessian language, not related to the Iberian language.

Early in the first millennium BC, several waves of Pre-Celts and Celts migrated from Central Europe, thus partially changing the peninsula's ethnic landscape into Indo-European space in its northern and western regions. In North-Western Iberia (Northern Portugal, Asturias and Galicia) a Celtic culture developed, the Castro culture, with a large number of hill forts and some fortified cities.

Proto-history

By the Iron Age, starting in the 7th century BC, the Iberian Peninsula consisted of complex agrarian and urban civilizations, either Pre-Celtic or Celtic (such as the Lusitanians, the Celtiberians, the Gallaeci, the Astur, or the Celtici, amongst others), the cultures of the Iberians in the eastern and southern zones and the cultures of the Aquitanian in the western portion of the Pyrenees.

The seafaring Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians successively settled along the Mediterranean coast and founded trading colonies there over a period of several centuries. Around 1100 BC, Phoenician merchants founded the trading colony of Gadir or Gades (modern day Cádiz) near Tartessos. In the 8th century BC, the first Greek colonies, such as Emporion (modern Empúries), were founded along the Mediterranean coast on the East, leaving the south coast to the Phoenicians. The Greeks coined the name Iberia, after the river Iber (Ebro). In the 6th century BC the Carthaginians arrived in the peninsula while struggling with the Greeks for control of the Western Mediterranean. Their most important colony was Carthago Nova (Latin name of modern day Cartagena).

History

Roman rule

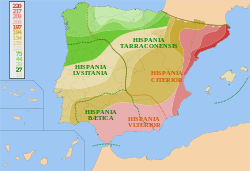

In 218 BC the first Roman troops invaded the Iberian Peninsula, during the Second Punic war against the Carthaginians, and annexed it under Augustus after two centuries of war with the Celtic and Iberian tribes and the Phoenician, Greek and Carthaginian colonies, resulting in the creation of the province of Hispania. It was divided into Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior during the late Roman Republic, and during the Roman Empire, it was divided into Hispania Taraconensis in the north-east, Hispania Baetica in the south and Lusitania in the south-west.

Hispania supplied the Roman Empire with food, olive oil, wine, and metal. The emperors Trajan, Hadrian, and Theodosius I, the philosopher Seneca, and the poets Martial and Lucan were born from families living on the peninsula.

Germanic kingdoms

In the early 5th century, Germanic tribes invaded the peninsula, namely the Suebi, the Vandals (Silingi and Hasdingi) and their allies, the Sarmatian Alans. Only the kingdom of the Suebi (Quadi and Marcomanni) would endure after the arrival of another wave of Germanic invaders, the Visigoths, who conquered all of the Iberian peninsula and expelled or partially integrated the Vandals and the Alans. The Visigoths eventually conquered the Suebi kingdom and its capital city Bracara (modern day Braga) in 584–585. They would also conquer the province of the Byzantine Empire (552–624) of Spania in the south of the peninsula and the Balearic Islands.

Islamic rule

In AD 711, a Muslim army invaded the Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania. Under Tariq ibn-Ziyad, the Islamic army landed at Gibraltar and brought most of the Iberian Peninsula under Islamic control in an eight-year campaign. Al-ʾAndalūs (Arabic الإندلس : possibly "Land of the Vandals"),[18][19] is the Arabic name given the Iberian Peninsula by its Muslim Berber and Arab conquerors.

From the 8th–15th centuries, the Iberian Peninsula was incorporated into the Islamic world and became a center of culture and learning, especially during the Caliphate of Cordoba, which reached its height under the rule of Abd ar-Rahman III. The Muslims, which were initially Arabs and Berbers, included local Iberian converts, the so-called Muladi, who formed the majority of the Iberian population by the year 1100. The Muslims were referred to by the generic name, Moors. Thus, before the so-called Reconquista gained momentum, the Iberian peninsula had been transformed from a mainly Romance-speaking Christian land into a mainly Arabic-speaking Muslim land. However, pockets of Arabic and Romance-speaking Christians called Mozarabs survived throughout al-Andalus, in addition to a large minority of Arabic-speaking Jews.

Reconquest

Many of the ousted Gothic nobles took refuge in the unconquered north Asturian highlands. From there, they aimed to reconquer their lands from the Moors; this war of reconquest is known as the Reconquista. Christian and Muslim kingdoms fought and allied among themselves. The Muslim taifa kings competed in patronage of the arts, the Way of Saint James attracted pilgrims from all Western Europe, and the Jewish population set the basis of Sephardic culture.[citation needed]

During the Middle Ages the peninsula housed many small states including Castile, Aragon, Navarre, León and Portugal. The peninsula was part of the Islamic Almohad empire until they were finally uprooted. The last major Muslim stronghold was Granada which was conquered by a combined Castilian and Aragonese force in 1492. Muslims and Jews throughout the period were variously tolerated or shown intolerance in different Christian kingdoms. However, after the conquest of Granada, all Muslims and Jews were ordered to convert to Christianity or face expulsion. Many Jews and Muslims fled to North Africa and the Ottoman Empire while others publicly converted to Christianity and became known respectively as Marranos and Moriscos. However, many of these continued to practice their religion in secret. The Moriscos revolted several times and were ultimately forcibly expelled from Spain in the early 17th century.

Post reconquest

The small states gradually amalgamated over time, with the exception of Portugal, even if for a brief period (1580–1640) the whole peninsula was united politically under the Iberian Union. After that point the modern position was reached and the peninsula now consists of the countries of Spain and Portugal (excluding their islands—the Portuguese Azores and Madeira Islands and the Spanish Canary Islands and Balearic Islands; and the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla), Andorra, French Cerdagne and Gibraltar.

Geography and geology

Overall characteristics

The Iberian Peninsula extends from the southernmost extremity at Punta de Tarifa (36°00′15″N 5°36′37″W / 36.00417°N 5.61028°W) to the northernmost extremity at Estaca de Bares Point (43°47′38″N 7°41′17″W / 43.79389°N 7.68806°W) over a distance between lines of latitude of about 865 km (537 mi) based on a degree length of 111 km (69 mi) per degree, and from the westernmost extremity at Cabo da Roca (38°46′51″N 9°29′54″W / 38.78083°N 9.49833°W) to the easternmost extremity at Cap de Creus (42°19′09″N 3°19′19″E / 42.31917°N 3.32194°E) over a distance between lines of longitude at 40° N latitude of about 1,155 km (718 mi) based on an estimated degree length of about 90 km (56 mi) for that latitude. The irregular, roughly octagonal shape of the peninsula contained within this spherical quadrangle was compared to an ox-hide by the geographer Strabo.[20]

About three quarters of that rough octagon is the Meseta Central, a vast plateau ranging from 610 to 760 m in altitude.[21] It is located approximately in the centre, staggered slightly to the east and tilted slightly toward the west (the conventional centre of the Iberian Peninsula has long been considered to be Getafe just south of Madrid). It is ringed by mountains and contains the sources of most of the rivers, which find their way through gaps in the mountain barriers on all sides.

Coastline

The coastline of the Iberian Peninsula is 3,313 km (2,059 mi), 1,660 km (1,030 mi) on the Mediterranean side and 1,653 km (1,027 mi) on the Atlantic side.[22] The coast has been inundated over time, with sea levels having risen from a minimum of 115–120 m (377–394 ft) lower than today at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to its current level at 4000 years BP.[23] The coastal shelf created by sedimentation during that time remains below the surface; however, it was never very extensive on the Atlantic side, as the continental shelf drops rather steeply into the depths. An estimated 700 km (430 mi) length of Atlantic shelf is only 10–65 km (6.2–40.4 mi) wide. At the 500 m (1,600 ft) isobath, on the edge, the shelf drops off to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[24]

The submarine topography of the coastal waters of the Iberian Peninsula has been studied extensively in the process of drilling for oil. Ultimately the shelf drops into the Bay of Biscay on the north (an abyss), the Iberian abyssal plain at 4,800 m (15,700 ft) on the west and Tagus abyssal plain to the south. In the north between the continental shelf and the abyss is an extension, the Galicia Bank, a plateau containing also the Porto, Vigo and Vasco da Gama seamounts, creating the Galicia interior basin. The southern border of these features is marked by Nazaré Canyon, splitting the continental shelf and leading directly into the abyss.

Rivers

The major rivers flow through the wide valleys between the mountain systems. These are the Ebro, Douro, Tagus, Guadiana and Guadalquivir. All rivers in the Iberian Peninsula are subject to seasonal variations in flow.

The Tagus is the longest river in the peninsula and, like the Douro, flows westwards with its lower course in Portugal. The Guadiana bends southwards and forms the border between Spain and Portugal in the last stretch of its course.

Mountains

The terrain of the Iberian Peninsula is largely mountainous. The major mountain systems are:

- The Pyrenees and their foothills, the Pre-Pyrenees, crossing the isthmus of the peninsula so completely as to allow no passage except by mountain road, trail, coastal road or tunnel. Highest point 3,404 m high Aneto in the Maladeta massif.

- The Cantabrian Mountains along the northern coast with the massive Picos de Europa. Highest point 2,648 m high Torre de Cerredo.

- The Galicia/Trás-os-Montes Massif in the Northwest made up of very old heavily eroded rocks.[25] Highest point 2,127 m high Pena Trevinca.

- The Sistema Ibérico, a complex system at the heart of the Peninsula, in its central/eastern region. It contains a great number of ranges and divides the watershed of the Tagus, Douro and Ebro rivers. Highest point 2,313 m high Moncayo.

- The Sistema Central, dividing the Iberian Plateau into a northern and a southern half and stretching into Portugal where the highest point of Portugal (1,993 m) is located in the Serra da Estrela. Highest point 2,592 m high Pico Almanzor in the Sierra de Gredos.

- The Montes de Toledo, also stretching into Portugal from the La Mancha natural region at the eastern end. Highest point 1,603 m high La Villuerca in the Sierra de Villuercas, Extremadura.

- The Sierra Morena, dividing the watershed of the Guadiana and Guadalquivir rivers. Highest point 1,332 m high Bañuela.

- The Baetic System, stretching between Cádiz and Gibraltar and stretching northeastwards reaching Alicante Province. It is divided in three subsystems:

- Prebaetic System. It begins west of the Sierra Sur de Jaén reaching the Mediterranean Sea shores in Alicante Province. Highest point 2,382 m high La Sagra.

- Subbaetic System In a central position within the Baetic Systems, stretching from Cape Trafalgar in Cádiz Province across Andalusia until the Region of Murcia.[26] Highest point 2,027 m (6,650 ft) high Peña de la Cruz in Sierra Arana.

- Penibaetic System, located in the far southeastern area stretching between Gibraltar across the Mediterranean coastal Andalusian provinces. It includes the highest point in the peninsula, 3,478 m high Mulhacén in the Sierra Nevada.[27]

Geology

The Iberian Peninsula contains rocks of every geological period from the Ediacaran to the Recent, and almost every kind of rock is represented. World class mineral deposits can also be found there. The core of the Iberian Peninsula consists of a Hercynian cratonic block known as the Iberian Massif. On the northeast this is bounded by The Pyrenean fold belt, and on the southeast it is bounded by the Betic Foldchain. These twofold chains are part of the Alpine belt. To the west, the peninsula is delimited by the continental boundary formed by the magma poor opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The Hercynian Foldbelt is mostly buried by Mesozoic and Tertiary cover rocks to the east, but nevertheless outcrops through the Iberian Chain and the Catalan Coastal Ranges.

Modern countries and territories

Political divisions of the Iberian Peninsula sorted by area:

| Country/ Territory |

Mainland population[28] | km2 | sq mi | % | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43,500,000 | align="right"|505,519 | 195,182 | 85% | occupies most of the peninsula | |

| 10,000,000 | align="right"|89,261 | 34,464 | 15% | occupies most of the west of the peninsula | |

| 12,035 | align="right"|540 | 210 | <1% | French Cerdagne is in the south side of the Pyrenees range between Spain and France, so it is technically located in the Iberian peninsula[29] | |

| 84,082 | align="right"|468 | 181 | <1% | a northern edge of the peninsula in the south side of the Pyrenees range between Spain and France | |

| 29,431 | align="right"|7 | 3 | <1% | a British overseas territory near the southernmost tip of the peninsula |

Urbanization

Major Urban Areas

| Urban Area | Country | Region | Population | Globalization Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid | Community of Madrid | 6,321,398[30] | Alpha | |

| Barcelona | |

Catalonia | 4,604,000[31] | Alpha- |

| Lisbon | |

Lisbon Region | 3,035,000[32] | Alpha- |

| Porto | |

Norte Region | 1,676,848[33] | Gamma- |

| Valencia | |

Community of Valencia | 1,564,145[34] | Gamma |

Major cities

| List of cities in the Iberian Peninsula by population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City/Town | Region & Country | Population (2011–12) | City/Town | Region & Country | Population (2011–12) | |||||

| 1 | Madrid | Madrid, Spain | 3,233,527 | 11 | Córdoba | Andalusia, Spain | 328,841 | |||

| 2 | Barcelona | Catalonia, Spain | 1,620,943 | 12 | Valladolid | Castile and León, Spain | 311,501 | |||

| 3 | Valencia | Valencia, Spain | 797,028 | 13 | Vigo | Galicia, Spain | 297,733 | |||

| 4 | Seville | Andalusia, Spain | 702,355 | 14 | Vila Nova de Gaia | Norte, Portugal | 288,749 | |||

| 5 | Zaragoza | Aragon, Spain | 679,624 | 15 | Gijón | Asturias, Spain | 277,554 | |||

| 6 | Málaga | Andalusia, Spain | 567,433 | 16 | L'Hospitalet | Catalonia, Spain | 257,057 | |||

| 7 | Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal | 547,631 | 17 | A Coruña | Galicia, Spain | 246,146 | |||

| 8 | Murcia | Murcia, Spain | 441,354 | 18 | Vitoria-Gasteiz | Basque Country, Spain | 242,223 | |||

| 9 | Bilbao | Basque Country, Spain | 351,629 | 19 | Porto | Norte, Portugal | 237,559 | |||

| 10 | Alicante | Valencia, Spain | 334,678 | 20 | Granada | Andalusia, Spain | 239,017 | |||

Various other notable cities are also present on the peninsula, like Elche (230,354), Oviedo (225,973), Badalona (220,977) and Terrassa (215 678) in Spain; and Braga (181,874), Amadora (175,558), Coimbra (102,455) and Setúbal (90,640) in Portugal.

Major metropolitan areas

The main metropolitan areas of the Iberian Peninsula are Madrid, Barcelona, Lisbon, Valencia, Porto, Seville, Bilbao, Málaga, Central Asturias (Gijón-Oviedo-Avilés), Alicante-Elche and Murcia.

Ecology

Forests

The woodlands of the Iberian Peninsula are distinct ecosystems. Although the various regions are each characterized by distinct vegetation, there are some similarities across the peninsula.

While the borders between these regions are not clearly defined, there is a mutual influence which makes it very hard to establish boundaries and some species find their optimal habitat in the intermediate areas.

East Atlantic flyway

The Iberian Peninsula in an important stopover on the East Atlantic flyway for birds migrating from northern Europe to Africa. For example, Calidis ferruginea rests in the region of Cadiz Bay.[35]

In addition to the birds migrating through, some seven million wading birds from the north spend the winter in the estuaries and wetlands of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly at locations on the Atlantic coast. In Galicia are the Ria de Arousa (a home of Grey Plover), Ria de Ortigueira, Ria de Corme and Ria de Laxe. In Portugal the Aveiro Lagoon hosts Recurvirostra avosetta, Ringed Plover, Grey Plover and Little Stint. Ribatejo Province on the Tagus River supports Recurvirostra arosetta, Grey Plover, Dunlin, Bar-tailed Godwit and Common Redshank. In the Sado Esturary are Dunlin, Eurasian Curlew, Grey Plover and Common Redshank. The Algarve hosts Red Knot, Greenshank and Turnstone. The Marismas de Guadalquivir region of Andalusia and the Salinas de Cádiz are especially rich in wintering wading birds: Kentish Plover, Ringed Plover, Sanderling, and Black-tailed Godwit in addition to the others. And finally, the Ebro delta is home to all the species mentioned above.[36]

Languages

Most modern languages of Iberia descend from Vulgar Latin, except for Basque which is of unknown origin. Throughout history (and pre-history), many different languages have been spoken in the Iberian Peninsula contributing to the formation and differentiation of the contemporaneous languages of Iberia, however most of them have become extinct or fallen into disuse. Basque is the only non-Indo-European surviving language in Iberia and Western Europe.

In modern times, Spanish (cf. 30 to 40 million speakers), Portuguese (cf. around 10 million speakers), Catalan (cf. around 9 million speakers), Galician (cf. around 3 million speakers) and Basque (cf. around half a million speakers) are the most widely spoken languages in the Iberian Peninsula. Spanish and Portuguese have expanded beyond Iberia to the rest of world, becoming global languages.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑

- ↑ Tom Zeller Jr. (23 October 2006). "The Internet Black Hole That Is North Korea". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ↑ Bill Powell (14 August 2007). "North Korea". Time. Archived from the original on 24 May 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ↑ "1823 - First American Macadam Road" (Painting - Carl Rakeman) US Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration (Accessed 2008-10-10)

- ↑ First known use in that sense dates to 1618."Iberian". Online Etymological Dictionary.

- ↑ Strabo. "Book III Chapter 1 Section 6". Geographica. "And also the other Iberians use an alphabet, though not letters of one and the same character, for their speech is not one and the same."

- ↑ Strabo; Horace Leonard Jones, Translator (MCMLXXXVIII). The Geography (in ancient Greek, English) II. Cambridge: Bill Thayer. p. 118, Note 1 on 3.4.19.

- ↑ I.163.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 III.4.19.

- ↑ III.37.

- ↑ III.17.

- ↑ III.4.11.

- ↑ "Iberia, Iberi". Félix Gaffiot's Dictionnaire Illustré Latin Français. Librairie Hachette. 1934.

- ↑ III.3.21.

- ↑ White, Horace; Jona Lendering. "Appian's History of Rome: The Spanish Wars (§§6–10)". livius.org. pp. Chapter 7. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ↑ "Polybius: The Histories: III.6.2". Bill Thayer.

- ↑ Case, H (2007). 'Beakers and Beaker Culture' Beyond Stonehenge: Essays on the Bronze Age in honour of Colin Burgess. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 237–254.

- ↑ Abraham Ibn Daud's Dorot 'Olam (Generations of the Ages): A Critical Edition and Translation of Zikhron Divrey Romi, Divrey Malkhey Yisra?el, and the Midrash on Zechariah. BRILL. 7 June 2013. p. 57. ISBN 978-90-04-24815-1. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Julio Samsó (1998). The Formation of Al-Andalus: History and society. Ashgate. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-86078-708-2. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ III.1.3.

- ↑ Fischer, T (1920). "The Iberian Peninsula: Spain". In Mill, Hugh Robert. The International Geography. New York and London: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 368–377.

- ↑ These figures sum the figures given in the Wikipedia articles on the geography of Spain and Portugal. Most figures from Internet sources on Spain and Portugal include the coastlines of the islands owned by each country and thus are not a reliable guide to the coastline of the peninsula. Moreover, the length of a coastline may vary significantly depending on where and how it is measured.

- ↑ Edmunds, WM; K Hinsby; C Marlin; MT Condesso de Melo; M Manyano; R Vaikmae; Y Travi (2001). "Evolution of groundwater systems at the European coastline". In Edmunds, W. M.; Milne, C. J. Palaeowaters in Coastal Europe: Evolution of Groundwater Since the Late Pleistocene. London: Geological Society. p. 305. ISBN 1-86239-086-X.

- ↑ "Iberian Peninsula – Atlantic Coast" (pdf). An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves. Global Ocean Associates. February 2004. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ Silurian graptolite biostratigraphy of the Galicia - Tras-os-Montes Zone (Spain and Portugal)

- ↑ Edited by W Gibbons & T Moreno, Geology of Spain, 2002, ISBN 978-1-86239-110-9

- ↑ Introduction to the Birds of Spain

- ↑ Population includes only the inhabitants of mainland Spain (excluding the Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla), mainland Portugal (excluding Madeira and Azores), Andorra and Gibraltar.

- ↑ For example, the Segre river, which goes west and then south to meet the Ebro, has its source in the French side.

- ↑ http://www.populationdata.net/index2.php?option=pays&pid=62&nom=espagne

- ↑ http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf

- ↑ http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf Demographia: World Urban Areas

- ↑ http://esa.un.org/wup2009/unup/index.asp?panel=2

- ↑ http://www.urbanaudit.org/CityProfiles.aspx?CityCode=ES003C&CountryCode=ES

- ↑ Hortas, Francisco; Jordi Figuerols (2006). "Migration pattern of Curlew Sandpipers Calidris ferruginea on the south-western coastline of the Iberian Peninsula" (pdf). International Wader Studies 19: 144–147. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Dominguez, Jesus (1990). "Distribution of estuarine waders wintering in the Iberian Peninsula in 1978–1982". Wader Study Group Bulletin 59: 25–28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iberian Peninsula. |

- Arioso, Pāolā; Diego Meozzi. "Iberian Peninsula•Links". Stone Pages. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- Flores, Carlos; Nicole Maca-Meyer; Ana M Gonzalez; Peter J Oefner; Peidong Shen; Jose A Perez; Antonio Rojas; Jose M Larruga; Peter A Underhill (2004). "Reduced genetic structure of the Iberian peninsula revealed by Y-chromosome analysis: implications for population demography" (pdf). European Journal of Human Genetics 12 (10): 855–863. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201225. PMID 15280900. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- Loyd, Nick (2007). "IberiaNature: A guide to the environment, climate, wildlife, geography and nature of Spain". Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- Silva, Luís Fraga de. "Ethnologic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (circa 200 B.C.). NEW VERSION #10" (in English, Portuguese, Latin). Associação Campo Arqueológico de Tavira, Tavira, Portugal. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

| |||||

Coordinates: 40°18′N 3°43′W / 40.300°N 3.717°W