Hypernasal speech

| Hypernasality | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | R49.21 |

| ICD-9 | 784.43 |

| MeSH | D014833 |

Hypernasal speech (also hyperrhinolalia or open nasality; medically known as Rhinolalia aperta from Latin rhinolalia: "nasal speech" and aperta: "open") is a disorder that causes abnormal resonance in a human's voice due to increased airflow through the nose during speech. It is caused by an open nasal cavity resulting from an incomplete closure of the soft palate and/or velopharyngeal sphincter.[citation needed]

Anatomy

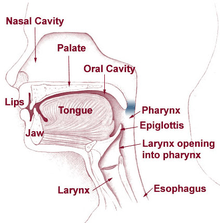

The palate comprises two parts, the hard palate (palatum durum) and the soft palate (palatum molle), which is connected to the uvula. The movements of the soft palate and the uvula are made possible by the velopharyngeal sphincter. During speech or swallowing, the uvula lifts against the back throat wall to close the nasal cavity. When producing nasal consonants (such as "m", "n", and "ng"), the uvula remains relaxed, thereby enabling the air to go through the nose.

The Eustachian tube, which opens near the velopharyngeal sphincter, connects the middle ear and nasal pharynx. Normally, the tube ensures aeration and drainage (of secretions) of the middle ear. Narrow and closed at rest, it opens during swallowing and yawning, controlled by the tensor veli palatini and the levator veli palatini (muscles of the soft palate). Children with a cleft palate have difficulties controlling these muscles and thus are unable to open the Eustachian tube. Secretions accumulate in the middle ear when the tube remains dysfunctional over a long period of time, which cause hearing loss and middle ear infections. Ultimately, hearing loss can lead to impaired speech and language development.[1][2]

Causes

The general term for disorders of the velopharyngeal valve is velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD). It includes three subterms: velopharyngeal insufficiency, velopharyngeal inadequacy, and velopharyngeal mislearning.

- Velopharyngeal insufficiency can be caused by an anatomical abnormality of the throat. It occurs in children with a history of cleft palate or submucous cleft, who have short or otherwise abnormal vela. Velopharyngeal insufficiency can also occur after adenoidectomy.

- Velopharyngeal incompetence is a defective closure of the velopharyngeal valve due to its lack of speed and precision. It is caused by a neurologic disorder or injury (e.g. cerebral palsy or traumatic brain injury).

- Sometimes children present no abnormalities yet still have hypernasal speech: this can be due to velopharyngeal mislearning, indicating that the child has been imitating or has never learned how to use the valve correctly.[3][4]

Diagnosis

There are several methods for diagnosing hypernasality.

- A speech therapist listens to and records the child while analysing perceptual speech.[5] In hypernasality, the child cannot produce oral sounds (vowels and consonants) correctly. Only the nasal sounds can be correctly produced.[6] A hearing test is also desirable.[7]

- A mirror is held beneath the nose while the child pronounces the vowels. Nasal air escape, and thus hypernasality, is indicated if the mirror fogs up.

- A pressure-flow technique is used to measure velopharyngeal orifice area during the speech. The patient must be at least three to four years old.

- A video nasopharyngeal endoscopy observes velopharyngeal function, movements of the soft palate, and pharyngeal walls. It utilises a very small scope placed in the back of the nasal cavity. The doctor will then ask the child to say a few words. The patient must be at least three to four years old to ensure cooperation.

- A cinefluoroscopy gives dynamic visualisation and can easier be applied to younger children, though it has the disadvantage of exposing the patient to radiation.[8]

- A nasometer calculates the ratio of nasality. The patient wears a headset, where the oral and nasal cavities are separated by a plate. On both sides of the plate are microphones. The ratio calculated by the nasometer indicates the amount of nasality, with a higher ratio indicating more nasality.[9]

Treatment

Speech therapy

In cases of muscle weakness or cleft palate, special exercises can help to strengthen the soft palate muscles with the ultimate aim of decreasing airflow through the nose and thereby increasing intelligibility. Intelligibility requires the ability to close the nasal cavity, as all English sounds, except "m", "n", and "ng", have airflow only through the mouth. Normally, by age three, a child can raise the muscles of the soft palate to close to nasal cavity.

Exercises

If a child finds it difficult to blow, pinching the nose can help regulate airflow. The child should then practise without pinching the nose, doing exercises such as blowing out a candle, blowing away tissues through a drinking straw, and, for sucking, drinking through a straw.

This exercises only work as treatments if hypernasality is small. Severe deviations should be treated surgically.[10]

Surgery

The two main surgical techniques for correcting the aberrations the soft palate present in hypernasality are the posterior pharyngeal flap and the sphincter pharyngoplasty. After surgical interventions, speech therapy is necessary to learn how to control the newly constructed flaps.[11]

Posterior pharyngeal flap

Posterior pharyngeal flap surgery is mostly used for vertical clefts of the soft palate. The surgeon cuts through the upper layers of the back of the throat, creating a small square of tissue. This flap remains attached on one side (usually at the top). The other side is attached to (parts of) the soft palate. This ensures that the nasal cavity is partially separated from the oral cavity. When the child speaks, the remaining openings close from the side due to the narrowing of the throat caused by the muscle movements necessary for speech. In a relaxed state, the openings allow breathing through the nose.[11]

Sphincter pharyngoplasty

Sphincter pharyngolplasty is mostly used for horizontal clefts of the soft palate. Two small flaps are made on the left and right side of the entrance to the nasal cavity, attached to the back of the throat. For good results, the patient must have good palatal motion, as the occlusion of the nasal cavity is mainly carried out by muscles already existing and functioning.[11]

|

Sound sample of snoring | |

| ICD-10 | R06.5 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 786.09 |

| DiseasesDB | 12260 |

| MeSH | D012913 |

Complications

The most common complications of the posterior pharyngeal wall flap are hyponasality, nasal obstruction, snoring, and sleep apnea. Rarer complications include flap separation, sinusitis, postoperative bleeding, and aspiration pneumonia. Possible complications of the sphincter pharyngoplasty are snoring, nasal obstruction, difficulty blowing the nose.

Some researches suggest that sphincter pharyngoplasty introduces less hyponasality and obstructive sleep symptoms than the posterior pharyngeal wall flap. Both surgeries have a favourable effect on the function of the Eustachian tube.[4] [12][11][13]

See also

- Rhinolalia clausa

References

- ↑ "Specifieke informatie over schisis per type schisis" [Specific information on each type of cleft lip and palate cleft] (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging voor Schisis en Craniofaciale Afwijkingen. 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Stegenga, B.; Vissink, A.; Bont, L.G.M. de (2000). Mondziekten en kaakchirurgie [Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery] (in Dutch). Assen: Van Gorcum. p. 388. ISBN 9789023235002.

- ↑ Kummer, Ann W. "Speech Therapy for Cleft Palate or Velopharyngeal Dysfunction (VPD)". Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Biavati, Michael J.; Sie, Kathleen; Wiet, Gregory J. (2 September 2011). "Velopharyngeal Insufficiency". Medscape Reference. WebMD LLC.

- ↑ Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital. "Otolaryngology (Ear, Nose and Throat)". Columbia University Medical Center.

- ↑ Gelder, van J. (1957). "De open neusspraak, pathogenese en diagnostiek". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde [Netherlands Journal of Medicine] (in Dutch) 101: 1005–10.

- ↑ Department of Otolarynology/Head and Neck Surgery. "Hypernasality – Velopharyngeal Insufficiency". Columbia University Medical Center.

- ↑ Probst, Rudolf; Grevers, Gerhard; Iro, Heinrich (2006). Basic Otorhinolaryngology a step-by-step learning guide (revised ed.). Stuttgart: Thieme. p. 401. ISBN 9783131324412. Unknown parameter

|translator=ignored (|others=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|illustrator=ignored (help) - ↑ KayPENTAX. "Nasometer II, Model 6450". PENTAX Medical Company.

- ↑ "Spraak en taal" [Speech and Language] (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging voor Schisis en Craniofaciale Afwijkingen.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 de Serres, Lianne M.; Deleyiannis, Frederic W.-B.; Eblen, Linda E.; Gruss, Joseph S.; Richardson, Mark A.; Sie, Kathleen C.Y. (April 1999). "Results with sphincter pharyngoplasty and pharyngeal flap". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 48 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00006-3.

- ↑ Sloan, GM (February 2000). "Posterior pharyngeal flap and sphincter pharyngoplasty: the state of the art.". The Cleft palate-craniofacial journal 37 (2): 112–22. doi:10.1597/1545-1569(2000)037<0112:PPFASP>2.3.CO;2. PMID 10749049.

- ↑ Ritsma, P.H.M.; Huffstadt, A.J.C.; Schutte, H.K. (1987). "De invloed van chirurgische behandeling van open neusspraak op horen en spreken". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde [Netherlands Journal of Medicine] (in Dutch) 131: 161–6. More than one of

|last1=and|last=specified (help)