Hyperbolic motion

In geometry, hyperbolic motions are isometric automorphisms of a hyperbolic space. Under composition of mappings, the hyperbolic motions form a continuous group. This group is said to characterize the hyperbolic space. Such an approach to geometry was cultivated by Felix Klein in his Erlangen program. The idea of reducing geometry to its characteristic group was developed particularly by Mario Pieri in his reduction of the primitive notions of geometry to merely point and motion.

Hyperbolic motions are often taken from inversive geometry: these are mappings composed of reflections in a line or a circle (or in a hyperplane or a hypersphere for hyperbolic spaces of more than two dimensions). To distinguish the hyperbolic motions, a particular line or circle is taken as the absolute. The proviso is that the absolute must be an invariant set of all hyperbolic motions. The absolute divides the plane into two connected components, and hyperbolic motions must not permute these components.

One of the most prevalent contexts for inversive geometry and hyperbolic motions is in the study of mappings of the complex plane by Möbius transformations. Textbooks on complex functions often mention two common models of hyperbolic geometry: the Poincaré half-plane model where the absolute is the real line on the complex plane, and the Poincaré disk model where the absolute is the unit circle in the complex plane. Hyperbolic motions can also be described on the hyperboloid model of hyperbolic geometry.[1]

This article exhibits these examples of the use of hyperbolic motions: the extension of the metric  to the half-plane, and in the location of a quasi-sphere of a hypercomplex number system.

to the half-plane, and in the location of a quasi-sphere of a hypercomplex number system.

Introduction of metric in upper half-plane

The points of the upper half-plane model HP are given in Cartesian coordinates as {(x,y): y > 0} or in polar coordinates as {(r cos a, r sin a): 0 < a < π, r > 0 }.The hyperbolic motions will be taken to be a composition of three fundamental hyperbolic motions. Let p = (x,y) or p = (r cos a, r sin a), p ∈ HP. The fundamental motions are:

- p → q = (x + c, y ), c ∈ R (left or right shift)

- p → q = (sx, sy ), s > 0 (dilation)

- p → q = ( r −1 cos a, r −1 sin a ) (inversion in unit semicircle).

Note: the shift and dilation are mappings from inversive geometry composed of a pair of reflections in vertical lines or concentric circles respectively.

Use of semi-circle Z

Consider the triangle {(0,0),(1,0),(1,tan a)}. Since 1 + tan2a = sec2a, the length of the triangle hypotenuse is sec a, where sec denotes the secant function. Set r = sec a and apply the third fundamental hyperbolic motion to obtain q = (r cos a, r sin a) where r = sec−1a = cos a. Now

- q – (½, 0)|2 = (cos2a – ½)2 +cos2a sin2a = ¼

so that q lies on the semicircle Z of radius ½ and center (½, 0). Thus the tangent ray at (1, 0) gets mapped to Z by the third fundamental hyperbolic motion. Any semicircle can be re-sized by a dilation to radius ½ and shifted to Z, then the inversion carries it to the tangent ray. So the collection of hyperbolic motions permutes the semicircles with diameters on y = 0 sometimes with vertical rays, and vice versa. Suppose one agrees to measure length on vertical rays by using the logarithm function:

- d((x,y),(x,z)) = |log(z/y)|.

Then by means of hyperbolic motions one can measure distances between points on semicircles too: first move the points to Z with appropriate shift and dilation, then place them by inversion on the tangent ray where the logarithmic distance is known.

For m and n in HP, let b be the perpendicular bisector of the line segment connecting m and n. If b is parallel to the abscissa, then m and n are connected by a vertical ray, otherwise b intersects the abscissa so there is a semicircle centered at this intersection that passes through m and n. The set HP becomes a metric space when equipped with the distance d(m,n) for m,n ∈ HP as found on the vertical ray or semicircle. One calls the vertical rays and semicircles the hyperbolic lines in HP. The geometry of points and hyperbolic lines in HP is an example of a non-Euclidean geometry; nevertheless, the construction of the line and distance concepts for HP relies heavily on the original geometry of Euclid.

Disk model motions

Consider the disk D = {z ∈ C : z z* < 1 } in the complex plane C. The geometric plane of Lobachevsky can be displayed in D with circular arcs perpendicular to the boundary of D signifying hyperbolic lines. Using the arithmetic and geometry of complex numbers, and Möbius transformations, there is the Poincaré disc model of the hyperbolic plane:

Suppose a and b are complex numbers with a a* − b b* = 1. Note that

- bz + a*|2 − |az + b*|2 = (aa* − bb*)(1 − |z|2),

so that |z| < 1 implies |(az + b*)/(bz + a*)| < 1 . Hence the disk D is an invariant set of the Möbius transformation

- f(z) = (az + b*)/(bz + a*).

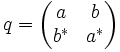

Since it also permutes the hyperbolic lines, we see that these transformations are motions of the D model of hyperbolic geometry. A complex matrix

with aa* − bb* = 1, which represents the Möbius transformation from the projective viewpoint, can be considered to be on the unit quasi-sphere in the ring of coquaternions.

References

- ↑ Miles Reid & Balázs Szendröi (2005) Geometry and Topology, §3.11 Hyperbolic motions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61325-6, MR 2194744

- Lars Ahlfors (1967) "Hyperbolic motions", Nagoya Mathematical Journal 29:163–5.

- Francis Bonahon (2009) Low-dimensional geometry : from euclidean surfaces to hyperbolic knots, Chapter 2 "The Hyperbolic Plane", pages 11–39, American Mathematical Society: Student Mathematical Library, volume 49 ISBN 978-0-8218-4816-6 .

- Victor V. Prasolov & VM Tikhomirov (1997,2001) Geometry, American Mathematical Society: Translations of Mathematical Monographs, volume 200, ISBN 0-8218-2038-9 .

- A.S. Smogorzhevsky (1982) Lobachevskian Geometry, Mir Publishers, Moscow.