Hwange National Park

| Hwange National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

| |

| Location | Matabeleland North, Zimbabwe |

| Nearest city | Hwange |

| Coordinates | 18°44′06″S 26°57′18″E / 18.735°S 26.955°ECoordinates: 18°44′06″S 26°57′18″E / 18.735°S 26.955°E |

| Area | 14,651 km² [1] |

| Established | 1928 as a Game Reserve[2] (1961 as a National Park)[1] |

| Governing body | Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority |

Hwange National Park (formerly Wankie Game Reserve) is the largest game reserve in Zimbabwe. The park lies in the west, on the main road between Bulawayo and the widely noted Victoria Falls and near to Dete.

History of the park

It was founded in 1928, with the first warden being by the 22-year-old Ted Davison.[2] He befriended the Manchester-born James Jones who was the stationmaster for the then Rhodesian Railways at Dete which is very near Hwange Main Camp. Jones managed incoming supplies for the park.[3]

This park is considered for inclusion in the 5 Nation Kavango - Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area.

Poaching incidents

In October 2013 it was discovered that poachers killed a large number of African elephants with cyanide after poisoning their waterhole. Conservationists have claimed the incident to be the highest massacre of animals in South Africa in 25 years.[4] [5] Two aerial surveys were carried to determine the extent of the deaths, and 19 carcasses were identified in the first survey[6] and a further 84 carcasses in the second survey.[7]

Three of the poachers were caught, arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced. All royal game and elephant poaching offences now have a mandatory 9 year sentence and the supply chain is also targeted - with a man arrested on October 21 trying to smuggle raw ivory out. Strong and serious action has been taken and the new minister has made poaching a major priority, including on prevention, not just prosecution.

In 2011, nine elephants, five lions and two buffalos were also killed by poachers.[8]

Features

Flora

The park is close to the edge of the Kalahari desert, a region with little water and very sparse, xerophile vegetation. The Kalahari woodland is dominated by Zambezi Teak, Sand Camwood (Baphia) and Kalahari bauhinia.[9] Seasonal wetlands form grasslands in this area.

The north and north-west of the park are dominated by mopane woodland.[2]

Although it has been argued that elephant populations cause change in vegetation structure,[10][11] some recent studies suggest that this is not the case, even with the large increases in elephant population recorded in the late 1980s.[12]

Fauna

The Park hosts over 100 mammal and 400 bird species,[13] including 19 large herbivores and eight large carnivores. All Zimbabwe's specially protected animals are to be found in Hwange and it is the only protected area where gemsbok and brown hyena occur in reasonable numbers.

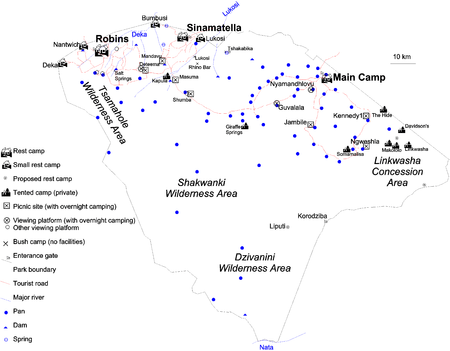

Grazing herbivores are more common in the Main Camp Wild Area and Linkwasha Concession Area, with mixed feeders more common in the Robins and Sinamatella Wild Areas, which are more heavily wooded.[14] Distribution fluctuates seasonally, with large herbivores concentrating in areas where intensive water pumping is maintained during the dry season.[15]

The population of African wild dogs to be found in Hwange is thought to be of one of the larger surviving groups in Africa today, along with that of Kruger National Park and Selous Game Reserve.[16][17] Other major predators include the lion, whose distribution and hunting in Hwange is strongly related to the pans and waterholes,[18] leopard, spotted hyena and cheetah.

Elephants have been enormously successful in Hwange and the population has increased to far above that naturally supported by such an area.[19] This population of elephants has put a lot of strain on the resources of the park. There has been a lot of debate on how to deal with this, with parks authorities implementing culling to reduce populations,[20] especially during 1967 to 1986. The elephant population doubled in the five years following the end of culling in 1986.[21]

National Parks Scientific Services co-ordinates two major conservation and research projects in the park:

- National Leopard Project, which is surveying numbers of leopard in order to obtain base-line data for later comparative analysis with status of leopard in consumptive (hunting) areas and Communal Land bordering the National Park.[22] This is carried out at Hwange in conjunction with the Wildlife Conservation and Research Unit of Oxford University and the Dete Animal Rescue Trust, a registered wildlife conservation Trust

- Painted Dog Project: The project aims to protect and increase the range and numbers of African wild dog both in Zimbabwe and elsewhere in Africa, and operates through the Painted Dog Conservation organisation in Dete.[23]

Geography and geology

Most of the park is underlain by Kalahari Sands.[24] In the north-west there are basalt lava flows of the Batoka Formation, stretching from south of Bumbusi to the Botswana border.[25][26][27] In the north-central area, from Sinamatella going eastwards, there are granites and gneisses of the Kamativi-Dete Inlier[28] and smaller inliers of these rocks are found within the basalts in the north-west.[29]

The north and north-west of the park are drained by the Deka and Lukosi rivers and their tributaries, and the far south of the park is drained by the Gwabadzabuya River, a tributary of the Nata River. There are no rivers in the rest of the park, although there are fossil drainage channels in the main camp and Linkwasha areas, which form seasonal wetlands. In these areas without rivers, grassy pan depressions and pans have formed. Some of these pans, such as many of the pans in the Shumba area, fill with rainwater, while others, such as Ngweshla, Shakwanki and Nehimba, are fed by natural groundwater seeps.[30][31] Many of the pans are additionally supplied by water pumped from underground by park authorities.[3]

Archaeological, historical and cultural sites

The Bumbusi National Monument, comprising ruins and rock carvings, is located on the northern edge of the park. There are also ruins at Mtoa and rock carvings at Deteema.[2]

Places of interest

Main Camp area

- Umtshibi camp, the headquarters of the park maintenance unit[3]

- Mtoa Ruins and Pan

- Dopi vlei, a fossil river containing Dopi Pan

- Kennedy vlei, a fossil river also known as Massumamalisa, containing the Kennedy 1, Kennedy 2 (named after Sir John Noble Kennedy, Governor of Southern Rhodesia[3]) and Massumamalisa (Somalisa) Pans

- Manga vlei, a fossil river also known as Amanga, containing the Manga Pans

- Nyamandhlovu Pan (the name refers to elephant meat) and game-viewing platform, one of the most popular game-viewing sites[2]

- Guvalala Pan and game-viewing platform, rehabilutated by scouts from Kent, UK in the 1990s[32]

- Dom Pan, where lion are often seen[2]

- Chivasa Pan

- Longone Pans, named after the chief cook during the first warden's time[3]

- Ngweshla Pan, a waterhole heavily frequented by game since before the park's proclamation[2]

- Shapi Pan, another waterhole heavily frequented by game since before the park's proclamation[2] and former headquarters of the park maintenance unit[3]

- Sibaya Pan

Sinamatella area

- Chawato Springs, a mineral spring north-west of Sinamatella on the Bumbusi road[33]

- Dabashure (Dobashura) Spring, a mineral spring west of Sinamatella[33]

- Salt Springs

- Tshakabika Hot Springs, a thermal spring east of Sinamatella[33]

- Lukosi River

- Mandavu Dam and picnic site

- Masuma Dam, with a thatched shelter overlooking the dam, as well as a camping ground and picnic site[34]

- New Inyantue Dam

- Tshompani Dam

- Dandari (Dandaro) Vlei, Plains and Pan

- Kapula Vlei

- Tiriga (Triga) Vlei, a fossil river

- Shuma Pans, a series of waterholes heavily frequented by game since before the park's proclamation,[2] with a hide and picnic site

- Nehimba Pan

- Tshompani Pan

Robins Camp area

- Deteema Dam, hide and picnic site

- Deteema fossil forest, silcified Dadoxylon trunks[2]

- Deka River, with Crocodile Pools hide

- Chingahobe River, a tributary of the Deka River and Chingahobe (Chingahobi) Dam

- Mahohoma River, a tributary of the Deka River

- Toms vlei and river, a tributary of the Deka River, named after the hunter Tom Saddler. Big Toms and Little Toms pans and hides are on the river.[2]

- Mbejane (Bejana) Pan, near the head of the Dandari vlei

Linkwasha concession area

- Inkwazi Vlei, a fossil river

- Makololo Pans and Plains

- Somavundhla Pan

Dzivanini wilderness area

- Liputi (Libuti) Camp and well. The name means a meeting place[2]

- Kordoziba Gate

- Nata River

- Gwabazabuya (Gwabadzabuya ) River

- Limpandi Dam

- Dzivanini (Sibanini) Pan and mudflats

Shakwanki wilderness area

- Shakwanki Pan; the name means ear and is a reference to its shape[3]

- Tamasanka Pan, on the Hunters Road from Tati to Mpandamatenga

- Xixi Amabandi Pan

Tsamhole wilderness area

- Tsamhole (Tsamahole) Pan and firetower, on the edge of extensive mudflats. The name refers to a waterhole owned by two people[2]

- Bumbumtsa Pan; the name meabs bumble bee[2]

- Reedbuck vlei, in the headwaters of the Deka River

Accommodation and camping

The park has three large rest camps and four smaller permanent camps.

Main Camp

This is the park headquarters, in the north-east, easily accessible by tarred road from the main Bulawayo–Victoria Falls road. There are a variety of self-catering accommodation, camping and caravan sites, a bar and restaurant and a supermarket.[13]

Sinamatella Camp

Sinamatella is in the north, several hours' drive through the park from Main Camp, or a shorter journey on a dirt road from the main Bulawayo–Victoria Falls road. Set on an escarpment above a waterhole, overlooking miles of bush. The camps has similar accommodation and camping facilities to Main Camp and a kiosk.[13]

Robins Camp

Robins is in the north-west, and has self-catering accommodation and camping sites but no other facilities. The camp is based around the old clock tower of the farm of Harold Robins, donated to the park in 1939.[13]

Nantwich Camp

Nantwich is located near Robins Camp, and has three self-catering lodges, built on a bluff overlooking a pan.[13] The lodges were not functional, and in a serious state of decay, in August 2013.

Bumbusi Exclusive Camp

Bumbusi is an exclusive camp for one party at a time, comprising self-catering accommodation for up to twelve persons. It is located twelve kilometres north-west of Sinamatella, near the Deka River and the Bumbusi National Monument.[13]

Lukosi Exclusive Camp

This is an exclusive camp for one party at a time, comprising self-catering accommodation for up to ten persons. It is located ten kilometres east of Sinamatella, near the Lukosi River and is only open in the rainy season.[13]

Deka Exclusive Camp

This is an exclusive camp for one party at a time, comprising self-catering accommodation for up to twelve persons. It is located twenty-five kilometres west of Robins, in headwaters of the Deka River and requires four-wheel drive for access.[13]

Bush Camps

These are remote camping sites with no facilities, for one party at a time. The bush camps are:

- Lukosi, on the Lukosi River east of Sinamatella

- Vhikani

- Rhino Bar, east of Sinamatella and north of Shumba

- Salt Springs, near a dam south-east of Robins

- Tshakabika, near hot springs east of Sinamatella, four wheel drive required.[13]

Camping and picnic sites

In addition, overnight camping is permitted at picnic sites and some of the platforms overlooking waterholes; bookings must be made in advance with the National Parks board. Camping is restricted to one party at a time and during the day, the facilities are open to all visitors. The sites are:

- Nyamandhlovu Platform

- Guvalala Platform

- Kennedy 1 Picnic Site

- Jambile Picnic Site

- Ngweshla Camp

- Shumba Camp

- Masuma Camp, a fully fenced site with two flush toilets, a shower and hide overlooking the dam[34]

- Mandavu Dam

- Deteema Dam hide[13]

Privately operated camps and sites

There are a number of privately operated tented camps within the park:

- Davison's Camp, in the far south-eastern corner of the park, comprises nine tents overlooking a waterhole.[35]

- Giraffe Springs, south of Shapi Pan in the central part of the park, is a tented camp overlooking Giraffe Pan. There are ten luxury tents, each with a viewing platform.[36]

- The Hide, between Kennedy 1 Pan and the railway line, is a tented camp opened in 1992. The camp is set in acacia woddland with views over a waterhole, and consists of ten luxury tents.[37]

- Kapula Lodge, on the Kapula vlei near Masuma Dam, consists of four luxury tents. The camp is self-catering.[38]

- Makololo Plains Camp, east of Ngweshla Pan, consists of two camps, one with nine rooms and one with five. Each camp is on raised platforms with elevated boardwalks, overlooking a waterhole.[39]

- Linkwasha Camp is east of Makololo, on a wide grassy plain[40]

- Somalisa Camp is west of Ngweshla, in the Kennedy vlei and consists of two camps, one with six tents and one with four tents, each overlooking a pan.[41][42]

Proposed camps

Long-term planning provides for the establishment of four further rest camps:

- Tshakabika, currently a bush camp, east of Sinamatella

- Two sites in the Linkwasha area, in the east of the park, currently a concession area

- Liputi in the far south[2]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hwange National Park. |

Gallery

-

Hwange elephant seeking relief from the afternoon heat

-

Sunset in Hwange

-

Masuma Dam

-

Elephants at a small pan

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 National Parks and Nature Reserves of Zimbabwe, World Institute for Conservation and Environment.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 G. Child and B. Reese (1977). Wankie National Park. National Parks and Wildlife Management of Rhodesia.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 T. Davison (1967). Wankie: The Story Of A Great Game Reserve. Books Of Africa. p. 211.

- ↑ "Poachers kill 300 Zimbabwe elephants with cyanide". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Zimbabwe elephants poisoned by cyanide". BBC News Online. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Colin Gillies (November 2013). Report on Hwange Elephant Poisoning (Report). Matabeleland Branch, Wildlife and Environment Zimbabwe.

- ↑ Colin Gillies (November 2013). 2nd Report Hwange Elephant Poisoning (Report). Matabeleland Branch, Wildlife and Environment Zimbabwe.

- ↑ "Zimbabwe elephants poisoned by poachers in Hwange". BBC News Online. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ M.A. Hyde, B.T. Wursten and P. Ballings (2010). "Flora of Zimbabwe: Outing no. 6: Visit to Hwange National Park and Bulawayo". Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Holdo, Ricardo M. (2007). "Elephants, Fire, and Frost Can Determine Community Structure and Composition in Kalahari Woodlands". Ecological Applications 17 (2): 558–68. doi:10.1890/05-1990. PMID 17489259.

- ↑ Cumming, D.H.M., Fenton, M.B., Rautenbach, I.L., Taylor, R.D., Cumming, G.S., Cumming, M.S., Dunlop, J.M., Ford, G.S., Hovorka, M.D., Johnston, D.S., Kalcounis, M.C., Mahlanga, Z., and C.V. Portfors (1997). "Elephants, woodlands and biodiversity in southern Africa". South African Journal of Science 93: 231–236.

- ↑ Valeix, Marion; Fritz, Hervé; Dubois, Ségolène; Kanengoni, Kwanele; Alleaume, Samuel; Saïd, Sonia (2007). "Vegetation structure and ungulate abundance over a period of increasing elephant abundance in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe". Journal of Tropical Ecology 23: 87. doi:10.1017/S0266467406003609.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 "Hwange National Park". Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ↑ Chamaillé-Jammes, Simon; Valeix, Marion; Bourgarel, Mathieu; Murindagomo, Felix; Fritz, Hervé (2009). "Seasonal density estimates of common large herbivores in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe". African Journal of Ecology 47 (4): 804–808. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2009.01077.x.

- ↑ Valeix, Marion (2011). "Temporal dynamics of dry-season water-hole use by large African herbivores in two years of contrasting rainfall in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe". Journal of Tropical Ecology 27 (2): 163. doi:10.1017/S0266467410000647.

- ↑ Woodroffe, Rosie; Ginsberg, Joshua R. (1999). "Conserving the African wild dog Lycaon pictus. I. Diagnosing and treating causes of decline". Oryx 33 (2): 132. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.1999.00052.x.

- ↑ Girman, D. J.; Vilà, C.; Geffen, E.; Creel, S.; Mills, M. G. L.; McNutt, J. W.; Ginsberg, J.; Kat, P. W. et al. (2001). "Patterns of population subdivision, gene flow and genetic variability in the African wild dog (Lycaon pictus)". Molecular Ecology 10 (7): 1703–23. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01302.x. PMID 11472538.

- ↑ Valeix, Marion; Loveridge, Andrew J.; Davidson, Zeke; Madzikanda, Hillary; Fritz, Hervé; MacDonald, David W. (2009). "How key habitat features influence large terrestrial carnivore movements: Waterholes and African lions in a semi-arid savanna of north-western Zimbabwe". Landscape Ecology 25 (3): 337. doi:10.1007/s10980-009-9425-x.

- ↑ B. Williamson (1975). "Seasonal distribution of elephant in Wankie National Park". Arnoldia.

- ↑ G. Child (2004). "Elephant Culling In Zimbabwe". Zimconservation Opinion 1: 1–6.

- ↑ Chamaillé-Jammes, Simon; Fritz, Hervé; Holdo, Ricardo M. (2007). "Spatial relationship between elephant and sodium concentration of water disappears as density increases in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe". Journal of Tropical Ecology 23 (6). doi:10.1017/S0266467407004531.

- ↑ "Zimbabwe National Leopard Survey". Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ↑ "Painted Dog Conservation Organisation: - End of Year Report 2011". Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ↑ J.C.Ferguson (1938). Geological reconnaissance in the Wankie Game Reserve (Report). Zimbabwe Geological Survey Technical Files.

- ↑ B.Lightfoot (1912). "The Geology of the North-Western Part of the Wankie Coalfield, Southern Rhodesia". Southern Rhodesia Geological Survey Bulletin 4 (1).

- ↑ R.L.A. Watson (1960). "The Geology and Coal Resources of the Country around Wankie, Southern Rhodesia". Southern Rhodesia Geological Survey Bulletin 48.

- ↑ B. Lightfoot (1914). "The Geology of the North-western part of the Wankie Coalfield". Southern Rhodesia Geological Survey Bulletin 4.

- ↑ N.H. Lockett (1979). "The Geology of the Country Around Dett". Rhodesia Geological Survey Bulletin 85.

- ↑ D. Love (1999). "Crystalline inliers to the south of Hwange". Geological Society of Zimbabwe Newsletter (July 1999): 5.

- ↑ Loveridge, A. J.; Hunt, J.E.; Murindagomo, F. (2006). "Influence of drought on predation of elephant (Loxodonta africana) calves by lions (Panthera leo) in an African wooded savannah". Journal of Zoology 270 (3): 523–530. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00181.x.

- ↑ Dudley, J. P.; Criag, G. C.; Gibson, D. ST. C.; Haynes, G.; Klimowicz, J. (2003). "Drought mortality of bush elephants in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe". African Journal of Ecology 39 (2): 187–194. doi:10.1046/j.0141-6707.2000.00297.x.

- ↑ "Zimbex expedition". Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 HB Maufe (1933). "A preliminary report on the mineral springs of Southern Rhodesia". Southern Rhodesia Geological Survey Bulletin 23.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 M Mitchell. "Walkabout in Hwange". African Expedition. Retrieved 2013-05-10.

- ↑ "Davison's Camp". Wilderness Safaris. 2011. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Giraffe Springs Camp". Safarimappers. 2007. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "The Hide Safari Camp". Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Kapula Self Catering Lodge". Afrizim. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Makololo Plains Camp". Safarimappers. 2007. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Linkwasha Camp". Safarimappers. 2007. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Somalisa Camp". African Bush Camps. 2010. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Somalisa Acacica Camp". African Bush Camps. 2010. Retrieved 2012-01-27.