Huon Peninsula campaign

| Huon Peninsula campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Pacific War | |||||||

.jpg) A Matilda tank, named "Clincher", moves towards Japanese strong points near Finschhafen, on 9 November 1943. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 9th Division

Attached in support: | 20th Division

85th Garrison Unit |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~13,100 | ~12,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~1,028 killed or wounded | ~5,500 killed | ||||||

| |||||

The Huon Peninsula campaign was a series of battles fought in north-eastern Papua New Guinea in 1943–1944 during the Second World War. The campaign formed the initial part of an offensive that the Allies launched in the Pacific in late 1943 and resulted in the Japanese being pushed north from Lae to Sio on the northern coast of New Guinea over the course of a four-month period. For the Australians, a significant advantage was gained through the technological edge that Allied industry had achieved over the Japanese by this phase of the war, while the Japanese were hampered by a lack of supplies and reinforcements due to Allied interdiction efforts at sea and in the air.

The campaign was preceded by an amphibious landing by troops from the Australian 9th Division east of Lae on 4 September 1943. This was followed by an advance west along the coast towards the town where they were to link up with 7th Division advancing from Nadzab. Meanwhile, Australian and US forces mounted diversionary attacks around Salamaua. Heavy rain and flooding slowed the 9th Division's advance, which had to cross several rivers along the way. The Japanese rear guard also put up a stiff defence and, as a result, Lae did not fall until 16 September, when troops from the 7th Division entered it ahead of the 9th, and the main body of the Japanese force escaped north. Less than a week later, the Huon Peninsula campaign was opened as the Australians undertook another amphibious landing further east, aimed at capturing Finschhafen.

Following the landing at Scarlet Beach, the Allies set about moving south to secure Finschhafen, which saw fighting around Jivevaneng also. In mid-October, the Japanese launched a counterattack against the Australian beachhead around Scarlet Beach, which lasted for about a week and resulted in a small contraction of the Australian lines and a splitting of their force before it was defeated. After this, the Australians regained the initiative and began to pursue the Japanese who withdrew inland towards the high ground around Sattelberg. Amidst heavy fighting and a second failed Japanese counterattack, Sattelberg was secured in late November and the Australians began an area advance to the north to secure a line between Wareo and Gusika. This was completed by early December, and was followed by an advance by Australian forces along the coast through Lakona to Fortification Point, overcoming strong Japanese forces fighting delaying actions.

The final stage of the campaign saw the Japanese resistance finally break. A swift advance by the Australians along the northern coast of the peninsula followed and in January 1944 they captured Sio. At the same time, the Americans landed at Saidor. After this, mopping up operations were undertaken by Allied forces around Sio until March. A lull period then followed in northern New Guinea until July when US forces clashed with the Japanese around the Driniumor River. This was followed by further fighting in November 1944 when the Australians opened a fresh campaign in Aitape–Wewak.

Background

Geography

The Huon Peninsula is situated along the north-east coast of Papua New Guinea, and stretches from Lae in the south on the Huon Gulf to Sio in the north along the Vitiaz Strait. Along the coast, between these two points, numerous rivers and streams cut the terrain.[1] Of these, the most prominent are the Song, Bumi and Mape Rivers.[2] These waterways flow from the mountainous interior which is formed through the conglomeration of the Rawlinson Range in the south, with the Cromwell Mountains in the east. These meet in the centre of the peninsula to form the Saruwaged Range massif, which joins the Finisterre Range further west.[1] Apart from a thin, flat coastal strip, at the time of the campaign, the area was thickly covered with dense jungle, through which very few tracks had been cut. The terrain was rugged and for the most part the tracks, until improved by engineers, were largely unpassable to motor transport and as a result throughout the campaign a large amount of the Allied resupply effort was undertaken on foot.[3]

During planning, the Allies identified three areas as key and decisive terrain in the area: the beach north of Katika, which was later codenamed "Scarlet" by the Allies, the 3,150-foot (960 m) high peak called Sattelberg 5 miles (8 km) to the south-west, which dominated the area due to its height, and Finschhafen, possessing a small airfield and sitting on the coast in a bay which offered protected harbour facilities 5.6 miles (9.0 km) south of Scarlet Beach.[2] The Japanese, too, regarded Sattelberg and Finschhafen as key areas.[4] In addition to these, they identified a ridge that ran between the village of Gusika on the coast, about 3.4 miles (5.5 km) north of Katika, and Wareo 4.66 miles (7.5 km) inland to the west. The importance of this ridge lay in the track that ran along it, over which the Japanese supplied their forces around Sattelberg. It also offered a natural barrier to any advance north from Finschhafen, making it a potential defensive line.[2]

Military situation

By 1943, Japanese expansionary moves in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) had ceased. Their advance in Papua New Guinea had been halted the previous year by the blocking action that Australian forces had fought along the Kokoda Track. Subsequent defeats at Milne Bay, Buna–Gona, Wau and on Guadalcanal had forced the Japanese on to the back foot. As a result of these victories, the Allies were able to seize the initiative in the region in mid-1943 and began making plans to continue to push the Japanese back in New Guinea.[5]

Allied planners began formulating their plans for the future direction of the fighting in the wider Pacific with a focus upon retaking the Philippines and the eventual capture of the Japanese Home Islands. The lynchpin to Japanese strength in the region was their main base at Rabaul. The reduction of this base came to be seen as a key tenet of success in the SWPA for the Allies and was formalised into Operation Cartwheel.[6]

In order to achieve this, the Allies needed access to a number of airbases in the region. Allied high commanders, including General Douglas MacArthur, directed that two airbases be secured: one at Lae and another at Finschhafen.[6] The capture of Lae would provide the Allies with a port to supply Nadzab and would facilitate operations in the Markham Valley. Gaining control of Finschhafen, and the wider Huon Peninsula, was an important precursor to conducting operations in New Britain by providing a natural harbour, and enabling control of the strategically important Vitiaz and Dampier Straits.[7][8]

Opposing forces

At the time, there were no US ground forces under MacArthur's command in action against the Japanese,[9] and the task of securing Finschhafen was allocated to Australian troops from the 9th Division. A veteran formation of the all-volunteer Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF), the 9th Division was vastly experienced, having fought in the North African campaign, where it had held Tobruk against a German onslaught earlier in the war and had been heavily engaged at the First and Second Battle of El Alamein.[6] In early 1943, the division had been brought back to Australia, and it had subsequently been reorganised to take part in jungle warfare.[10] With an establishment of 13,118 men,[11] the division consisted of three brigades of infantry – the 20th, 24th and 26th – each consisting of three battalions, along with organic battalion-level engineer, pioneer, artillery, and armoured formations attached at divisional level. In support of the 9th Division, Militia infantry units from the 4th Brigade would also take part in the fighting after the initial fighting. American forces would also be involved, mainly providing logistical, naval and engineering support.[6]

.jpg)

Air support was provided by No. 9 Operational Group RAAF, which included several Royal Australian Air Force squadrons such as No. 4 Squadron RAAF, flying CAC Boomerangs and Wirraways,[12] and No. 24 Squadron RAAF equipped with Vultee Vengeance dive bombers; these units undertook numerous close air support and resupply missions throughout the campaign.[13] American Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and Lockheed P-38 Lightnings from the 348th and 475th Fighter Groups were also used to provide fighter cover for Allied shipping,[14][15] while heavy and medium bombers from the Fifth Air Force carried out strategic bombing missions to reduce Japanese airbases around Wewak and New Britain, and raided Japanese lines of communication in concert with PT boats.[16] Due to the impracticalities of using wheeled transport in the jungle, Allied logistics was undertaken primarily by means of water transport such as landing craft and barges which moved supplies along the coast, with overland supply to combat units being completed by New Guinean labourers and,[17] at times, by Australian combat troops themselves, which were re-roled temporarily to undertake portage tasks as required,[18] and augmented where possible with jeeps.[17]

The main Japanese force in the campaign was provided by the XVIII Army under the command of Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi and was headquartered at Madang.[19] This force consisted of three divisions – the 20th, the 41st and the 51st – and a number of smaller forces which included naval infantry and garrison units.[20] Around the Finschhafen area in mid-September 1943, the main forces were drawn from the 20th Division's 80th Infantry and 26th Field Artillery Regiments, the 41st Division's 238th Infantry Regiment, the naval 85th Garrison Unit and a company from the 51st Division's 102nd Infantry Regiment.[21] These forces were under the command of Major General Eizo Yamada, commander of the 1st Shipping Group,[22] although tactical command was devolved at local level due to the geographical spread of the Japanese units. These units were situated across a broad area between the Mongi River, east of Lae to Arndt Point, Sattelberg, Joangeng, Logaweng, Finschhafen, Sisi and on Tami Island.[23] The largest concentrations were around Sattelberg and Finschhafen,[21] where the main forces came under the command of Lieutenant General Shigeru Katagiri, commander of the 20th Division.[24] The strength and efficiency of the Japanese units had been reduced by disease, and their employment in road construction tasks between Madang and Bogadjim.[25]

Like the Allies, the Japanese also relied on water transport to ferry supplies and reinforcements around the New Guinea, using a force of three submarines to avoid interdiction by Allied aircraft which had previously inflicted heavy casualties during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.[26] These submarines were augmented by barges, although they were limited in supply and were subject to attack by Allied aircraft and PT boats.[27] Once the supplies had been landed, resupply parties were used to carry the stores overland on foot along a number of key tracks to their main troop concentrations around Sattelberg and Finschhafen.[2] Air support was provided by the 4th Air Army, consisting primarily of the 7th Air Division and 14th Air Brigade, along with some elements from the 6th Air Division.[14] Based in Wewak,[28] the Japanese aircraft were mainly used to escort Japanese shipping and attack Allied shipping around the main beachhead during the campaign, with a secondary task of undertaking ground attack missions in support of Japanese troops.[14][29] The 11th Naval Air Fleet, based at Rabaul, also undertook anti-shipping missions.[30] Despite having these units available, heavy Allied bombing of Japanese airfields around Wewak in August 1943 greatly reduced the number of aircraft available to the Japanese and limited their ability to apply airpower throughout the campaign.[31]

The Japanese force lacked for transport, engineer and logistical support and was hampered by a lack of cohesion due to its disparate command structure and poor infrastructure.[19] In contrast, the Australian force had fought together in previous campaigns and was backed up by a formidable logistical support base that could deliver them a technological and industrial superiority that the Japanese were unable to match.[32]

Prelude

Following MacArthur's directive to secure the airfields at Lae and Finschhafen, the Commander-in-Chief Allied Forces, South West Pacific Area, General Thomas Blamey, an Australian, ordered the capture of the Huon Peninsula. The 9th Division under Major General George Wootten was tasked with the job.[6] The initial focus was upon securing Lae. The Allies formulated a plan to achieve this that would see the 9th Division conduct an amphibious landing east of Lae, while the 7th Division would move by air to Nadzab in the Markham Valley, which had been secured by parachute troops from the US 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 2/4th Field Regiment. From Nadzab, the 7th Division would advance on Lae from the south to support the 9th Division's drive towards Lae.[33] At the same time, the Australian 3rd Division and the US 162nd Infantry Regiment would fight a diversionary action around Salamaua.[34]

After training in Queensland and at Milne Bay in New Guinea, the 9th Division embarked upon US ships assigned to Rear Admiral Daniel Barbey's naval task force – VII Amphibious Force – as part of what was the "largest amphibious operation...undertaken by Allied forces in the South-West Pacific" to that point in the war.[35] The 20th Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Victor Windeyer, was chosen to spearhead the assault with a landing at a beach 16 miles (26 km) to the east of Lae.[33] In preparation, early on 4 September 1943, five destroyers laid down a heavy bombardment that lasted six minutes.[36] Upon its conclusion, the 2/13th Infantry Battalion led the 20th Brigade ashore, with the brigade's other two battalions, the 2/15th and 2/17th, coming ashore shortly afterwards in the second and third waves. Unopposed on the ground, the Australian infantry quickly began to move inland as further reinforcements arrived.[37] About 35 minutes after the initial landing, as the Australian divisional headquarters and the 2/23rd Infantry Battalion were coming ashore, a small force of Japanese aircraft attacked the landing craft carrying the infantry ashore. As a result, two of these craft were heavily damaged and numerous casualties inflicted, including the 2/23rd's commanding officer, who was killed when a Japanese bomb landed on the bridge of LCI-339.[38]

Further Japanese air attacks came in the afternoon. A force of about 70 Japanese aircraft, coming from bases on New Britain, were beaten off over Finschhafen. Another group, however, achieved success around Morobe, attacking empty transports that were making their egress from Finschhafen, while off Cape Ward Hunt another group attacked an Allied convoy carrying follow-on forces, including the rest of Brigadier David Whitehead's 26th Brigade.[39] Aboard LST-471, 43 were killed and another 30 wounded, while eight were killed and 37 wounded on LST-473.[40] This did not prevent the flow of supplies and the arrival of further reinforcements in the shape of the 24th Brigade, under Brigadier Bernard Evans, the following day.[41] The Australians then began the arduous advance west towards Lae, passing through "thick jungle, swamps, kunai grass and numerous rain-swollen rivers and streams" which, along with heavy rain, slowed their progress.[42] On the night of 5/6 September, the Japanese launched an attack on the lead Australian battalion, but they were unable to prevent its advance. At this point, the 26th Brigade moved inland to strike towards Lae from the north-east while the 24th carried the advance along the coast.[42]

At this point, the 9th Division's advance began to be hampered by a lack of supplies which, along with the rugged terrain, resulted in slow progress.[42] It was not until 9 September that they reached the Busu River. The 2/28th Infantry Battalion was leading the Australian advance at this stage and the soldiers waded across. The current was strong and many of the men – 13 of whom drowned – were swept downstream. Nevertheless, the 2/28th was able to establish a beachhead west of the river. At this point, heavy rain began to fall again, and the river rose once more, preventing any other units from crossing. This effectively isolated the single Australian battalion, which was then subjected to repeated attacks by the Japanese.[43] On 14 September, the 26th Brigade was able to force its way across and the advance continued. Along the coast the 24th Brigade was held up by a determined Japanese defence in front of the Butibum River, which was the final crossing before Lae. The stream was finally forded on 16 September, by which time Lae had fallen to troops from the 7th Division.[44]

In the fighting for Lae over 2,200 Japanese were killed. In contrast, the Australian casualties were considerably lighter, with the 9th Division losing 77 killed and 73 missing.[45] Despite the Allied success in capturing Lae, the Japanese had achieved a "creditable defence", which had not only slowed the Allied advance, but had allowed the bulk of the Japanese forces in the vicinity to get away, withdrawing north into the Huon Peninsula, where they could continue to fight on.[44]

Campaign

Finschhafen

Lae had fallen sooner than the Allies had anticipated and they exploited the advantage quickly. The first phase of the new campaign consisted of an amphibious landing by Allied troops north of Siki Cove near the confluence of the Siki River and south of the Song at a beach codenamed "Scarlet". Positioned further east on the peninsula from Lae, in terms of strategic importance, Finschhafen overshadowed Lae in the minds of the Allied planners,[46] due to its potential to support operations across the Vitiaz Strait into New Britain.[44] As a result of faulty intelligence, which underestimated the size of the Japanese force in the area, the assault force chosen by the Allied commanders consisted of only a single Australian infantry brigade – the 20th.[47] Meanwhile, the 7th Division would move north-west from Lae in a separate campaign, advancing through the Markham and Ramu Valleys towards the Finisterre Range.[48]

After a short period of preparation, the 20th Brigade's landing took place on 22 September 1943. It was the first opposed amphibious landing that Australian forces had made since Gallipoli.[49] Navigational errors resulted in the troops being landed on the wrong beaches, with some of them coming ashore at Siki Cove and taking heavy fire from the strong Japanese defences in pillboxes and behind obstacles. After re-organising on the beach, the Australians pushed inland. The Japanese put up stiff resistance around the high ground at Katika, but were eventually forced back.[47] By the end of the day, having suffered 94 casualties, the Australians had secured a beachhead "several kilometres" deep.[50] Late in the day, a force of around 30 Japanese bombers, escorted by up to 40 fighters,[51] from the Wewak-based 4th Air Army based was sent to attack Allied shipping around Finschhafen.[28] Forewarned by the destroyer USS Reid, which was serving as an air picket and fighter controller in the Vitiaz Strait,[52] the Allies were able to concentrate five squadrons of US fighter aircraft over the convoy and in the aerial battle that followed 39 Japanese aircraft were shot down and the raid turned back.[15][51]

The next day the Australians commenced their advance south towards the village of Finschhafen, about 5.6 miles (9.0 km) south of the landing beach,[53] with the 2/15th Infantry Battalion leading the way to the Bumi River. The Japanese had established strong defences along the river's southern bank, which the Australians attempted to outflank by sending a force to the west, climbing through steep terrain. Once they had located a suitable place to cross the river, they began wading across but were fired upon by a group of Japanese naval infantry who were positioned on a high feature overlooking the river. Despite taking casualties, the Australians were able to establish themselves south of the Bumi and at that point the 2/13th Infantry Battalion began to advance on Finschhafen from the west. Meanwhile, the 2/15th attacked the left flank of the Japanese that had opposed their crossing.[47] After advancing up the steep slope under fire, sometimes on their hands and knees, the 2/15th took the position at the point of the bayonet, killing 52 Japanese in close combat.[47]

The continued advance south by the Australians spread them thin on the ground. Due to concerns that their western flank was exposed, the 2/17th Infantry Battalion was sent along the Sattelberg track to deflect any Japanese thrusts from there.[54] At Jivevaneng, the battalion was stopped and there the Japanese 80th Infantry Regiment launched a series of determined attacks against them, trying to break through to the coast.[24]

At this point, Australian fears of a Japanese counterattack grew and they requested reinforcements from their higher commander, General Douglas MacArthur. However, the request was denied as MacArthur's intelligence staff believed that there were only 350 Japanese in the vicinity.[54] Actually, there were already 5,000 Japanese around Sattelberg and Finschhafen while throughout early October this number grew to 12,000 as they began to prepare for their planned counterattack.[55] The Australians received some reinforcements in the shape of the 2/43rd Infantry Battalion. The arrival of this unit meant that the 2/17th, deadlocked around Jivevaneng, could be freed for the advance on Finschhafen, thus enabling the entire 20th Brigade to concentrate on that objective.[54]

After an attack across the Ilebbe Creek by the 2/13th Infantry Battalion, which cost the Australians 80 casualties on 1 October,[47] the Japanese naval troops which were holding Finschhafen began to withdraw.[56] On 2 October, the town fell to the Australians and the Japanese abandoned the Kakakog Ridge amidst heavy Australian air and artillery attacks.[57] Once the 20th Brigade was established in Finschhafen, it linked up with the 22nd Infantry Battalion, a Militia infantry battalion. This unit had cleared the coastal area in the south of the peninsula, advancing from Lae over the mountains. Meanwhile, the Japanese that had been around Finschhafen withdrew back into the mountains around Sattelberg.[47][57] Allied air operations from the airfield at Finschhafen commenced on 4 October.[56] The following day, the 2/17th Infantry Battalion was sent to Kumawa to follow up the retreating Japanese forces, and for the next couple of days minor clashes resulted before it established itself at Jivevaneng again on 7 October.[47]

Japanese counterattack

The Japanese had begun planning a counterattack during the Australian advance on Finschhafen. The main part of the 20th Division was moved down from Madang as the Japanese began concentrating their forces around Sattelberg,[47] with the main force arriving there on 11 October.[56] The Japanese plans became known to the Australians through captured documents and by mid-October 1943 the Australian 24th Infantry Brigade had been brought up to reinforce the 20th.[55] When the Japanese counterattack came, the first wave fell upon the 24th Brigade around Jivevaneng on 16 October but the attack, having been put in a piecemeal fashion,[58] was pushed back.[12] The next day Japanese aircraft attacked Allied forces around Scarlet Beach and this was followed shortly an amphibious landing which was all but destroyed at sea by fire from American and Australian anti-aircraft and machine-guns.[12] It was during this assault that an American soldier, Private Nathan Van Noy, from the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, performed the actions for which he was later posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.[59] Only a small number of Japanese managed to make it ashore amidst the devastating fire and, by the following day, these all had been killed or wounded by Australian infantry conducting mopping up operations.[60]

The main elements of the Japanese counterattack had penetrated the forward and thinly stretched Australian lines throughout the previous night. The Japanese exploited the gaps in the line between the 2/28th Infantry and the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalions,[60] and launched an attack towards the coast with the objective of capturing the high ground 1.7 miles (2.7 km) west of Scarlet Beach,[12] and splitting the Australian forces at Katika.[56]

The 24th Brigade withdrew from Katika and the high ground to the north of Scarlet Beach to strengthen the defences around the beachhead in response to the Japanese penetration,[61] while the 20th Brigade was moved into position along the Siki Creek to block the Japanese advancing towards Finschhafen.[60] Australian resistance was strong despite giving up the advantage of the high ground, with field and anti-aircraft artillery engaging at ranges as short as 220 yards (200 m) "over open sights". As result, the Japanese attack was turned away from Scarlet Beach and channelled down Siki Creek. Nevertheless, they succeeded in breaking through to Siki Cove by 18 October and effectively drove a wedge between the 24th Brigade in the north and the 20th Brigade in the south.[12] In doing so, they captured a considerable amount of Allied supplies, including ammunition, weapons and rations, helping to replenish their own dwindling supplies.[62]

During the night of 18/19 October, the Japanese cut the route that the Australians were using to supply the 2/17th defending Jivevaneng and established a road block astride the Jivevaneng–Sattelberg road.[12] The 2/17th and a number of other Australian units, such as most of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion, as well as part of the 2/28th, became isolated behind Japanese lines.[60] In order to keep them supplied, emergency air drops of ammunition were flown in by pilots of No. 4 Squadron RAAF.[63]

At this point, the Japanese attack began to slow. The strength of the Australian resistance had resulted in heavy casualties and as a result the Japanese were unable to take advantage of the gains they had made. This allowed the Australians to begin their own counter-thrust on 19 October. Following a heavy artillery preparation, the 2/28th Infantry Battalion retook Katika.[60] The Australians received reinforcements the next day with a squadron of Matilda tanks from the 1st Tank Battalion arriving by landing craft at Langemak Bay amidst tight security that was aimed at keeping their arrival secret from the Japanese. Accompanying the tanks was the 26th Brigade; its arrival meant that the 9th Division had now been committed in its entirety.[60] Although on 21 October the Japanese withdrew from Siki Cove, the fighting around Katika continued for four more days as the Japanese attempted to retake it against fierce resistance from the 2/28th.[64] Katagiri gave the order for his forces to withdraw back to Sattelberg by 25 October, when it became apparent that the counterattack had been defeated.[65] The Japanese had suffered 1,500 casualties, including 679 killed. In comparison, the Australians had lost 49 killed and 179 wounded.[66]

Sattelberg

An old German mission, Sattelberg lay roughly 5 miles (8.0 km) inland and due to its size and height – 3,150 feet (960 m) – its possession by a large force of Japanese posed a significant threat in the minds of the Australian commanders. It offered good observation of the coastal area and could serve as a base for the Japanese to disrupt Australian lines of communication. As a result, Wootten decided to capture it.[67] The main approach to the mission lay along the road that ran through Jivevaneng. Although the main thrust of the Japanese counterattack had been turned back by 25 October, Jivevaneng was still in doubt and the 2/17th Infantry Battalion was still fending off Japanese attacks. Consequently, the 2/13th Infantry Battalion was brought up, and together with the 2/17th they began clearing operations. These were completed by the night of 2/3 November when the Japanese ceased their assault and withdrew from around the village.[60] Follow up actions on 6 November resulted in the destruction of the road-block that the Japanese had established on the Sattelberg road east of Jivevaneng in October.[66]

With Jivevaneng decided, the Australians turned advancing west towards Sattelberg. The force that was chosen for this was the recently arrived 26th Brigade, which would be supported by nine Matildas of the 1st Tank Battalion. At the same time, the 4th Brigade, a Militia formation detached from the 5th Division, was brought up to relieve the 26th Brigade of garrison duties around Finschhafen.[66] The tanks moved up to Jivevaneng under the cover of an artillery barrage to drown out their noise in an effort to keep their presence secret until the start of the advance.[66] On 16 November, the 2/48th Infantry Battalion, supported by the artillery of the 2/12th Field Regiment and the machine guns of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion, captured Green Ridge overlooking the track, which was the designated forming-up point for the advance on Sattelberg, which began the following day.[68]

The advance got off to a bad start initially as it was hampered in the inland area by the prevalent rugged terrain which consisted largely of thick jungle and steep "razor-back" ridges.[60] The ability of forces to manoeuvre in this environment was limited and Whitehead, the Australian brigade commander, determined to utilise infiltration tactics as a result. He sent columns of infantry, no more than company-size, to advance along "narrow fronts" ahead of one or two tanks, with engineers in support to improve the track or deal with "booby traps" or mines as they were found.[69] The brigade's scheme of manoeuvre saw the 2/48th advance up the main track as the 2/23rd and 2/24th Infantry Battalions protected its flanks to the south and north respectively.[60] None of the Australians' first day objectives were met. The 2/48th was held up in front of Coconut Ridge by stubborn resistance after one of the tanks was disabled and two others were damaged. On the flanks, both the 2/23rd and 2/24th also came up against strong defences in the shape of pillboxes and machine-gun nests, suffering many casualties and Coconut Ridge did not fall until the following day.[70]

The advance then continued, and by 20 November Steeple Tree Hill had been secured by the 2/48th, with the 2/23rd advancing towards its southern portion from Kumawa,[71] while the 2/24th continued to strike north towards the "2200" feature.[72] Initially, this had just been conceived as a holding action to protect the 2/48th's flank, but due to the slow progress on the main track, at this point, the Whitehead decided to change his strategy, determining to use a "double-pronged" attack, with the 2/24th also attempting to break through to Sattelberg from the north.[72]

Elsewhere, in the north-east, closer to the coast, the establishment of observation posts on key terrain overlooking Japanese main supply routes by Australian forces began affecting the supply situation of the Japanese forces around Sattelberg, as supply parties were ambushed as they attempted to bring up food and ammunition.[73] The Australians were also short of supplies and, as a result, they paused on 21 November while supplies were brought up to them, before the advance resumed the following day. The main thrust aimed for a jink where the track turned north. Here the 2/48th turned to the north-east, while the 2/23rd left the track and began advancing north-west towards the "3200" feature, which lay west of Sattelberg;[74] the 2/24th, coming up against increasingly steep terrain and very strong Japanese defences around the 2200 feature, unsuccessfully attempted to bypass the position and strike towards Sattelberg.[75] The same day, in the north, the Japanese attempted another counterattack on 22 November, aiming to relieve the supply situation around Sattelberg and to recapture Finschhafen. The counterattack failed, as it was blunted by the Australian depth position around Pabu and, lacking the tempo of the earlier counterattack in October, it was ultimately beaten back, with little affect on Australian operations around Sattelberg.[76]

The fortress around Sattelberg was methodically reduced by intensive Allied bombing which lasted five days, coming to an end on 23 November.[77] The same day, Japanese aircraft also undertook ground support operations with a force of 44 Japanese aircraft attacking Australian positions round Jivevaneng.[78] This did not change the situation around Sattelberg as by then the Australians had reached its southern slopes and the following day they began probing forward towards its summit. Throughout the day they launched a number of attacks, but heavy defensive fire pushed these back until a platoon under the command of Sergeant Tom Derrick fought its way almost to the top, with Derrick leading the way, destroying 10 Japanese positions with grenades as he went.[79] With the Australians having secured a toehold just below the summit for the night, the Japanese withdrew under the cover of darkness and the following morning the advance to the mission was completed. For his feat, Derrick later received the Victoria Cross, his nation's highest military decoration.[80]

Pabu

Although the main effort of the Australian forces shortly after the landing at Scarlet Beach in late September was upon the drive towards Finschhafen, some effort was made by troops from the Papuan Infantry Battalion to carry out reconnaissance north of the main engagement area towards Bonga and Gusika and throughout early October the 2/43rd Battalion conducted a number of patrols in the area.[80] Intelligence gathered from these patrols and through aerial reconnaissance evidence revealed that the Japanese were using tracks in the area to supply the forces in the west atop Sattelberg.[61] In response, the Australians established observation posts and after further reconnaissance it became apparent to the Australians that one hill, which they named "Pabu" and which was part of a larger feature dubbed "Horace the Horse",[81] was the key to holding the area.[61] Its location placed it directly astride the main Japanese supply route, and its proximity to the Australian forward positions at North Hill meant that it was in range of Australian artillery and could therefore be occupied by a small force that could be defended by indirect fire.[61] In mid-October, however, amidst the Japanese counterattack, Brigadier Bernard Evans, commander of the 24th Brigade, had ordered the withdrawal of Australian forces on Pabu as he had sought to reduce Australian lines in order to defend the beachhead.[61]

After the October counterattack was turned back, the Australians sought to regain the initiative. Evans was replaced by Brigadier Selwyn Porter and Wootten decided to establish a position in depth behind the Japanese forward line, deciding to once again establish a force at Pabu.[82] On 19/20 November, three companies from the 2/32nd Infantry Battalion, under the command of Major Bill Mollard, occupied the position, and began to attack the Japanese resupply parties that were moving through the area, inflicting heavy casualties.[83]

Meanwhile, the commander of the Japanese XVIII Army, Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi, ordered Katagiri to launch another counterattack. The supply situation was acute by this stage, with ammunition running low and troops being limited to one-third of their daily rations, nevertheless the counterattack was scheduled for 23/24 November.[84] However, the Australian occupation of Pabu and the threat it posed to the Japanese supply route, forced the Japanese commander to bring his schedule forward,[65] and to divert some of the effort away from the recapture of Finschhafen and upon the Australian forces advancing towards Sattelberg in the south.[85]

In an effort to retake Pabu and the ground north of the Song River, a force consisting of two Japanese battalions, from the 79th and 238th Infantry Regiments, advanced south along the coastal track from Bonga.[86] From 22 November, the Japanese attacked the Australians around North Hill, which were defended by the 2/43.[87] This effectively cut off the Australian forces on Pabu, which now only consisted of two companies from the 2/32nd and over the course over the next three days they were subjected to almost continual attack. On 25 November, the Japanese assaults had been blunted that the Australians began to push reinforcements forward. The two remaining companies of the 2/32nd were sent forward on 26 November, supported by four Matilda tanks and artillery, struck forward towards Pabu to reinforce its garrison which was under its heaviest attack since it had been occupied.[88] They arrived on Pabu and in the process secured "Pino Hill" to the south.[89]

The following day, the Japanese called a halt to their attack on the Australian right,[65] and subsequently troops from the 2/28th Infantry Battalion were then sent to the east to secure the position's flanks. On 29 November, the 2/32nd was relieved by the 2/43rd. In doing so, it was struck by a heavy Japanese artillery bombardment which killed or wounded 25.[89] Over the 10 days that the 2/32nd had held Pabu, Mollard's force had endured repeated mortar and artillery fire,[80][90] and repeated attacks, but with the assistance of strong artillery support,[87] it had held its ground and in doing so had helped blunt the force of the Japanese counterattack at a time when Australian forces were making heavy progress towards the Japanese fortress at Sattelberg.[91] Later, the Japanese commanding general, Adachi, pinpointed the Australian capture of Pabu as one of the main reasons for the defeat of his force during the Huon Peninsula campaign.[92] Losses during the fighting around Pabu were 195 Japanese and 25 Australians killed, and 51 Australians wounded.[93]

Wareo–Gusika

With a second counter-thrust having been beaten back again and the loss of Sattelberg, Katagiri decided to fall back to the north, to form a defensive line around Wareo to wait for the Australians to follow up their victories with a further advance.[65] By this time, Katagiri's forces were suffering from a manpower shortage due to a lack of reinforcements and the supply situation had still not been rectified.[78] The Australian commander, Wootten, was keen to regain the initiative and he decided to resume the advance in the north with a view to securing the remainder of the Huon Peninsula.[94] The first stage of Wootten's plan involved advancing north and securing a line along a ridge that ran between Gusika, on the coast, and Wareo, which was 4.35 miles (7.0 km) inland.[18] It was to take place in two main drives: the 26th Brigade, having secured Sattelberg, would advance to Wareo on the left, and the 24th Brigade would advance on the right, up the coast to secure Gusika and two large water features about 2 miles (3.2 km) inland near the head of the Kalueng River, known collectively to the Australians as "the Lakes". A third, minor advance would take place in the centre to Nongora and the Christmas Hills, responsibility for which was given to the 20th Brigade.[95]

The advance on the right saw the 2/28th Infantry Battalion advance towards Bonga and with armoured support, captured Gusika on 29 November.[96] Later they crossed the Kalueng River and advanced towards the Lagoon further north along the coast.[97] The 2/43rd Battalion then advanced from Pabu towards "Horace's Ears", where the Japanese made a stand which held the Australians up briefly.[98] They then continued east towards the Lakes, where they were to take over responsibility for the central drive from the battalions of the 20th Brigade, who were then to be rested for the next stage of the campaign.[99]

In the centre, the 2/15th Infantry Battalion set out from Katika to capture Nongora on 30 November.[89] They advanced over broken countryside and after the lead company had crossed the Song River, they were engaged by machine-gun fire from a strong defensive position. This held them up briefly, until the other companies came up.[97] Skirting the position, they continued on towards Nongora where they stopped short of the high ground and established a defensive position for the night. The following morning, the Australians launched a costly and unsuccessful company-level attack against the ridge, but after darkness the Japanese abandoned the position, allowing the 2/15th to occupy it and then clear Nongora on 2 December.[97] Following this, they began sending fighting patrols out towards the Christmas Hills area in the west, and to the east towards the Lakes to make contact with the 24th Brigade.[100]

The link up occurred on 3 December and the following day a composite force from the 2/32nd and 2/43rd Infantry Battalions took over the advance to the Christmas Hills, which were secured on 7 December after the Japanese abandoned the position in the wake of a series of flanking moves by the Australians, an intense artillery and mortar bombardment and a frontal assault.[101]

Meanwhile, on the left, the advance began on 28 November. On the map, Wareo was roughly 3.4 miles (5.5 km) away from Sattelberg, however, due to the nature of the terrain, the actual distance to be travelled was estimated at being four times that. For the advancing Australian infantrymen, the burden was made even greater by heavy rain which turned the tracks over which they were advancing into a muddy morass that could not be traversed by motor transport. This, coupled with the unavailability of New Guineans to serve as bearers, meant that the Australians had to carry almost all of their own supplies on their backs. In an effort to keep the advance moving, the entire 2/24th Infantry Battalion was tasked with carrying supplies for the 2/23rd, which led the advance from Sattelberg.[18]

On 30 November, the 2/23rd reached the Song, fighting its way across and the next day, after sharp fighting amidst a renewed local counterattack by Japanese forces,[78] Kuanko was taken. To the north of the abandoned village, the Japanese were positioned in strength and they launched a strong counterattack, which retook the vital high ground for them but was checked from progressing further by a heavy Australian artillery bombardment.[102] At this stage, the 2/24th Infantry Battalion was released from its portage task and it was sent west to conduct a flanking movement around the Japanese position, cutting the Kuanko–Wareo track and capturing Kwatingkoo and Peak Hill early on 7 December, following a Japanese withdrawal. From there, it was a short march on to Wareo, which the Australians secured early the next day.[102]

The main Japanese force then began to withdraw north towards Sio, however, sporadic fighting continued around Wareo over the following week as isolated pockets of Japanese resistance conducted rearguard operations to allow their comrades to get away. The most significant action during this time took place on 11 December when the 2/24th Infantry Battalion attacked the 2200 feature north-east of Wareo, near the Christmas Hills, which resulted in 27 Japanese killed.[102]

Sio

The next phase of the campaign involved the advance of Australian forces along the coast towards Sio, about 50 miles (80 km) from Finschhafen.[103] Following the capture of Gusika, the responsibility for the first part of the advance to Sio was taken over by the infantry of the 4th Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Cedric Edgar.[104] They were brought forward from Finschhafen early in December where they had been undertaking garrison duties and on 5 December,[105] the 22nd Infantry Battalion began the advance, crossing the Kalueng River.[102] Lacking the experience that the 2nd AIF units had, the Militia battalions advanced more cautiously than they might otherwise have done so.[104] They were supported by American landing craft equipped with rockets, which bombarded Japanese positions along the coast,[106] while the expansion of the airfield around Finschhafen and the establishment of a naval facility there enabled the Allies to use Consolidated PBY Catalina aircraft and PT boats to further attack Japanese resupply efforts.[106]

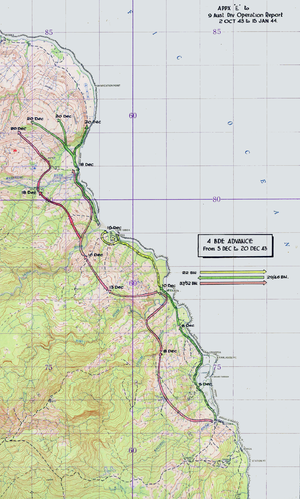

As they advanced, the Australians came up against stiff resistance, as Japanese forces in the area fought hard to buy time for the forces falling back from Wareo by delaying the Australian advance.[78] Initially, the 22nd's attack was turned back; however, fire support from artillery and armour helped overcome this opposition, and the advance continued with the 22nd and 29th/46th Infantry Battalions advancing in turns up the coast with the 37th/52nd moving on their left further inland.[102] Lakona was reached on 14 December and, after finding the Japanese forces there to be positioned in strength, the 22nd Battalion worked its way around the town, enveloping the Japanese defenders and pushing them back to the cliffs, where on 16 December tanks were used to launch the final attack.[107] After this, the 29th/46th took over the coastal advance to Fortification Point, which it reached alongside the 37th/52nd on 20 December, crossing the Masaweng River and gaining the high ground to its north.[102]

The 4th Brigade suffered 65 killed and 136 wounded on top of rising casualties from disease and was replaced by the 20th Brigade at this point.[107] The 26th Brigade took over flank protection duties inland.[108] The advance then rolled quickly as Japanese morale broke and organised resistance diminished. Large gains were made against only limited resistance, which often amounted to minor skirmishes against small groups of Japanese. Hubika fell on 22 December with no opposition,[109] and Wandokai two days later. Blucher Point was reached on 28 December, where the 2/13th Infantry Battalion regained contact with the retreating Japanese and fought a sharp contact. Elsewhere, that same day, US forces landed further west at Saidor.[110]

This sealed the Japanese decision to quit the Sio area, and over the course of two weeks the Australians advanced swiftly up the coast, overcoming only "sporadic opposition"[96] as the Japanese continued to withdraw to the west towards Madang, seeking to avoid being cut off by the forces at Saidor.[111] The 2/15th took over the advance on 31 December, reaching Nunzen on New Years Day. The Sanga River was crossed on 2 January 1944 and the following day the 2/17th reached Cape King William. Further river crossings followed at the Sazomu and Mangu Rivers as Kelanoa fell on 6 January; next, the Dallman and Buri Rivers were forded as Scharnhorst Point was rounded on 9 January.[96] After a final action was fought at Nambariwa, the 2/17th finally reached Sio on 15 January.[112]

Aftermath

The operations undertaken by the 9th Division during the Huon Peninsula campaign were the largest by the Australian Army to that point of the war.[9] Backed up by significant industrial resources which provided them with a significant technological edge over the Japanese,[32] the Australian campaign destroyed what offensive capabilities the Japanese had in the region,[113] and enabled them to gain control of vital sea lanes of communication and airfields that furthered their ability to conduct offensive operations in north-western New Guinea and New Britain.[106] After the capture of Sio, on 21 January 1944 the 9th Division handed over to the 5th Division.[114] The 5th Division was a Militia formation and its take over was part of the wider Australian plan to re-allocate the veteran divisions of the 2nd AIF to more intense operations elsewhere, namely the Philippines,[115] while using the less experienced Militia formations to undertake the lower intensity work required to mop-up isolated pockets of Japanese resistance. In the event, the 9th Division was precluded from taking part in the fighting in the Philippines due to inter-Allied politics,[116] and it was subsequently employed in Borneo in 1945.[117] Meanwhile, one of the 5th Division's component formations, the 8th Brigade, conducted mopping up operations around Sio throughout January into February and March 1944.[114] They also effected a link up with US forces around Saidor.[118]

The 9th Division suffered 1,082 battle casualties during its involvement in the fighting on the Huon Peninsula. This included 283 men who were killed in action and one who was listed as "missing". These casualties were relatively light in the wider context of the division's involvement in the war as they had suffered more than twice that number during the fighting around El Alamein earlier in the war. Regardless, a number of factors combined to make the fighting on the Huon Peninsula, in the words of one participant, "harder and more nerve-racking" than that which the 9th had taken part in before.[113] These included the harsh terrain, the closeness of the combat, and the lack of hot food, water and motor transport.[113] Disease also proved significant and during the campaign up to 85 per cent of the division's personnel were ineffective due to illness at some stage.[113]

Nevertheless, the most significant factor was the fighting qualities of the Japanese soldier. One Australian veteran, Sergeant Charles Lemaire, who had previously fought against the Germans at El Alamein with the 2/17th Infantry Battalion, described the Japanese as "tenacious, brave, self-sacrificing". In the minds of the Australian soldiers, the Japanese had a reputation for being tough opponents and for not taking prisoners.[113] Despite this perception amongst the Australians, there was a sense of confidence in their technological superiority.[119] For the Japanese soldiers, the technological edge that the Australians possessed and their relatively abundant supply of ammunition and artillery and air support was the main psychological factor that governed their perceptions of the Australians as enemy.[120] In order to counter this, Japanese commanders exhorted their troops to draw upon "spiritual strength" to achieve victory. In the end, although many of the significant actions of the campaign were infantry engagements which occurred a long way from the Australian base areas where their technological superiority was limited,[6] the Australians' use of combined arms tactics ultimately proved decisive.[113] Although preliminary aerial bombardment, particularly that which was employed around Sattelberg, proved largely ineffective in terms of its physical effects, it did serve to reduce Japanese morale. Used in combination with artillery preparation, which caused significant casualties, considerable disruption was caused to Japanese lines of communications that were already stretched.[121] Suffering from ammunition shortages that limited their fire support, the Japanese defenders were overwhelmed by Australian infantry that had a level of artillery support that was unprecedented for an Australian division in the Pacific,[122] and who advanced in concert with tanks that they employed in a manner that exploited the element of surprise.[121]

Japanese losses during the campaign amounted to a significantly higher total than those of the Allies, although exact numbers have not been established. About 12,500 Japanese soldiers participated in the campaign and about 5,500 are believed to have been killed.[123] Some sources indicate a possibly higher toll. With only 4,300 Japanese reaching Sio at the end of the campaign, it is possible that the figure is closer to 7-8,000.[112][113] A significant amount of war materiel was also lost during the campaign. Of the 26 field artillery pieces that the Japanese possessed in the region, 18 were captured by the Australians during the campaign, while 28 out of their 36 heavy machine-guns were also lost.[113]

At the start of the campaign, the Australian Army had been the only ground force engaging in combat with the Japanese in the region. By the end, though, the involvement of US forces in the region had increased as the US Army took over responsibility for the main Allied effort from the Australians.[9] Elsewhere, the 7th Division's advance towards the Finisterre Range saw the capture of Shaggy Ridge and a subsequent advance towards Bogadjim and then Madang, which fell in April.[124] In July and August, US forces subsequently clashed with Japanese forces, including some of those that had escaped from the Huon Peninsula, around the Driniumor River.[125] Meanwhile, the Australian Army's efforts in the Pacific were scaled back,[9] and it was not be until late 1944 and early 1945, when several campaigns were launched in Bougainville, New Britain, Aitape–Wewak and Borneo, that it undertook major campaigns against the Japanese again.[126]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Johnston 2005, p. iv.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Coates 1999, p. 99.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 213.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 287.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Johnston 2005, p. 1

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 298.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 189.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Johnston 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ Palazzo 2004, p. 91.

- ↑ Palazzo 2001, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Johnston 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Odgers 1968, p. 68.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Miller 1959, p. 195.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Odgers 1968, p. 82.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 218.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Mallett 2004, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Johnston 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Coates 1999, p. 93.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Coates 1999, p. 92.

- ↑ Tanaka 1980, p. 177.

- ↑ Tanaka 1980, p. 178.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Tanaka 1980, p. 180.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 41 & 194.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, p. 228.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Tanaka 1980, p. 179.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, pp. 230–233.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 219.

- ↑ Miller 1959.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Johnston 2005, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Johnston 2002, p. 147.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 200.

- ↑ Johnston 2002, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 330.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 331.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, pp. 331–332.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 334.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, pp. 334–335.

- ↑ Johnston 2002, pp. 147–150.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Johnston 2005, p. 3.

- ↑ Maitland 1999, p. 78.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Johnston 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, p. 153.

- ↑ Masel 1995, p. 178.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 47.6 47.7 Maitland 1999, p. 80.

- ↑ Johnston 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 70.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Dexter 1961, p. 466.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 193.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 98.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Johnston 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Johnston 2005, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 Tanaka 1980, p. 68.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Johnston 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Miller 1959, p. 220.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 164–165

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 60.6 60.7 60.8 Maitland 1999, p. 81.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 Coates 1999, p. 195.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, p. 232.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, pp. 7 & 36.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 Tanaka 1980, p. 69.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 Johnston 2005, p. 8.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 242.

- ↑ Johnston 2002, p. 167

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 330.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Coates 1999, p. 217.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 218.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 222.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 245.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 225.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 Willoughby 1966, p. 233.

- ↑ Johnston 2002, p. 180.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Maitland 1999, p. 82.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 199.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 194–197.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 634.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Maitland 1999, p. 83.

- ↑ Coates 1999, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Maitland 1999, p. 87.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 203.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 204.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, p. 9.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 206.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 658.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 332.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Maitland 1999, p. 88.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Dexter 1961, p. 664.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 663.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 671.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, pp. 665 & 670.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 673.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 102.3 102.4 102.5 Maitland 1999, p. 89.

- ↑ Miller 1959, pp. 220–221.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Coates 1999, p. 241.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 243.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 Miller 1959, p. 221.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Johnston 2005, p. 12.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 245.

- ↑ Coates 1999, p. 246.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, p. 240.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Maitland 1999, p. 90.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 113.3 113.4 113.5 113.6 113.7 Johnston 2005, p. 13.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Keogh 1965, p. 395.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 396.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, pp. 429–431.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 432.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 769.

- ↑ Johnston 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Williams & Nakagawa 2006, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Coates 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Palazzo 2004, p. 89.

- ↑ Tanaka 1980, p. 70.

- ↑ Johnston 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ Drea 1984, pp. 14–18.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, pp. 345–429.

References

- Coates, John (1999). Bravery Above Blunder: The 9th Australian Division at Finschhafen, Sattelberg, and Sio. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-550837-8.

- Coates, John (2004). "The War in New Guinea 1943–44: Operations and Tactics". In Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey. The Foundations of Victory: The Pacific War 1943–1944. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. ISBN 0-646-43590-6.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Dexter, David (1961). The New Guinea Offensives. Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1—Army. Volume VII (1st ed.). Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2028994.

- Drea, Edward J. (1984). Defending the Driniumor: Covering Force Operations in New Guinea, 1944 (PDF). Leavenworth Papers, No. 9. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- Johnston, Mark (2002). That Magnificent 9th: An Illustrated History of the 9th Australian Division 1940–46. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-643-7.

- Johnston, Mark (2005). The Huon Peninsula 1943–1944. Australians in the Pacific War. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of Veterans' Affairs. ISBN 1-920720-55-3.

- Johnston, Mark (2007). The Australian Army in World War II. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-123-6.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). The South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Productions. OCLC 7185705.

- Maitland, Gordon (1999). The Second World War and its Australian Army Battle Honours. East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-975-8.

- Mallett, Ross (2004). "Logistics in the South-West Pacific 1943–1944". In Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey. The Foundations of Victory: The Pacific War 1943–1944. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. ISBN 0-646-43590-6.

- Masel, Philip (1995) [1961]. The Second 28th: The Story of a Famous Battalion of the Ninth Australian Division (2nd ed.). Swanbourne, Western Australia: John Burridge Military Antiques. ISBN 0-646-25618-1.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 1355535.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) – Volume II. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 246580191.

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army. A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551507-2.

- Palazzo, Albert (2004). "Organising for Jungle Warfare". In Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey. The Foundations of Victory: The Pacific War 1943–1944. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. ISBN 0-646-43590-6.

- Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theater During World War II. Tokyo: Japan Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society. OCLC 9206229.

- Williams, Peter; Nakagawa, Naoko (October 2006). "The Japanese 18th Army in New Guinea". Wartime (Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial) (36): 58–63. ISSN 1328-2727.

- Willoughby, Charles (1966). Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – Part I. Reports of General MacArthur. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 187072014.