Humboldt squid

| Humboldt squid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Humboldt squid swarm around ROV Tiburon, possibly attracted to its lights | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Teuthida |

| Family: | Ommastrephidae |

| Subfamily: | Ommastrephinae |

| Genus: | Dosidicus Steenstrup, 1857 |

| Species: | D. gigas |

| Binomial name | |

| Dosidicus gigas (d'Orbigny, 1835) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas), also known as jumbo squid, jumbo flying squid, pota or diablo rojo, is a large, predatory squid living in the waters of the Humboldt Current in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Dosidicus gigas is the only species of the genus Dosidicus of the subfamily Ommastrephinae, family Ommastrephidae.

Humboldt squid are among the largest of squids, reaching a mantle length of 1.5 m (4.9 ft). They have a reputation for aggression towards humans, though this behavior may possibly only manifest during feeding times. Like other members of the subfamily Ommastrephinae, they possess bioluminescent photophores and are capable of quickly changing body coloration (metachrosis). They notably rapidly flash red and white while hunting, earning them the name diablo rojo (Spanish for 'red devil') among fishermen. They can live for up to two years.

They are most commonly found at depths of 200 to 700 m (660 to 2,300 ft), from Tierra del Fuego to California. Recent findings suggest the range of this species is spreading north into the waters of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska.[1][2] They are fished commercially, predominantly in Mexico and Peru.

Behavior and general characteristics

Humboldt squid are carnivorous marine invertebrates that move in shoals of up to 1,200 individuals. They swim at speeds of up to 24 km/h (15 mph; 13 kn) propelled by water ejected through a hyponome (siphon) and by two triangular fins. Their tentacles bear suckers lined with sharp teeth with which they grasp prey and drag it towards a large, sharp beak.

Although Humboldt squid have a reputation of being aggressive, there is some disagreement on this subject. Recent research suggests they are only aggressive while feeding; at other times, they are quite passive. Their behavior while feeding often extends to cannibalism and they have been seen to readily attack injured or vulnerable squid of their own shoal. This behavior may account for a large proportion of their rapid growth.[3][4] Some scientists claim the only reports of aggression towards humans have occurred when reflective diving gear or flashing lights have been present as a provocation. Roger Uzun, a veteran scuba diver and amateur underwater videographer who swam with a swarm of the animals for about 20 minutes, said they seemed to be more curious than aggressive.[5] In circumstances where these animals are not feeding or being hunted, they exhibit curious and intelligent behavior.[6]

Electronic tagging has shown Humboldt squid undergo diel vertical migrations, which bring them closer to the surface from dusk to dawn.[7] Humboldt squid are thought to have a lifespan of only about one year, although larger individuals may survive up to two years.[8] They may grow to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in mantle length (ML)[9][10] and weigh up to 50 kg (100 lb).[8] Generally, the mantle (or body) constitutes about 40% of the animal's mass, the fins (or wings) about 12%, the arms and tentacles about 14%, the outer skin about 3%, the head (including eyes and beak) about 5%, with the balance (26%) made up of the inner organs.[citation needed]

Distribution

The Humboldt squid lives at depths of 200 to 700 m (660 to 2,300 ft) in the eastern Pacific (Chile, Peru), ranging from Tierra del Fuego north to California. It gets its name from the Humboldt Current, in which it lives, off the coast of South America. Recently, the squid have been appearing farther north, as far as British Columbia.[11] They have also ventured into Puget Sound.[12]

Though they usually prefer deep water, between 1,000 and 1,500 squid washed up on the Long Beach Peninsula in southwest Washington in the fall of 2004[13] and red algae was a speculated cause for the fall 2012 beaching of an unspecified number of juvenile squid (average length 1.5 feet) at Monterey Bay over a two-month period.[14]

Behavior

They often approach prey quickly with all ten appendages extended forward in a cone-like shape. Upon reaching striking distance, they will open their eight swimming and grasping arms, and extend two long tentacles covered in sharp 'teeth', grabbing their prey and pulling it back towards a parrot-like beak, which can easily cause serious lacerations to human flesh. The whole process takes place in seconds.

Recent footage of shoals of these animals demonstrates a tendency to meet unfamiliar objects aggressively. Having risen to depths of 130–200 m (430–660 ft) below the surface to feed (up from their typical 700-metre (2,300-ft) diving depth, beyond the range of human diving), they have attacked deep-sea cameras and rendered them inoperable. Reports of recreational scuba divers being attacked by Humboldt squid have been confirmed.[15][16] One particular diver, Scott Cassell,[17] who has spent much of his career videotaping this species, has developed body armor to protect against attacks.[18] Each of the squid's suckers is ringed with sharp teeth, and the beak can tear flesh, although they are believed to lack the jaw strength to crack heavy bone.[3]

Ecology

The Humboldt squid feeds primarily on small fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, and copepods. The squid uses its barbed tentacle suckers to grab its prey and slices and tears the victim's flesh with its beak and radula. Another method of hunting, is pulling the prey to great depths until it faints. The Humboldt squid is also known to quickly devour larger prey when hunting in groups. Until recently, claims of cooperative or coordinated hunting in Dosidicus gigas were considered unconfirmed and without scientific merit.[19] However, research conducted between 2007 and 2011, published in June 2012, indicates this species does engage in cooperative hunting.[20]

Scientists suspect the recent expansion of the squid's range north along the west coast of the US is the result of some combination of overfishing of longer-lived apex predators and higher temperatures.[11][21]

Fishing

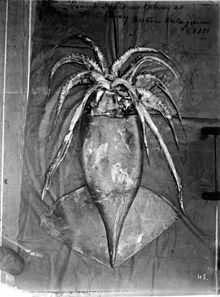

Humboldt squid as taken at Port Otway, western Patagonia, 1888 |

A 52 lb (24 kg) specimen caught off the southern Californian coast displays deep red chromatophoric coloring |

Commercially, this species has been caught to serve the European community market (mainly Spain, Italy, France and Ireland), Russia, China, Japan, Southeast Asian and increasingly North and South American markets.

Fisherman catch squid at night. Lights from the fishing boats reflect brightly on the plankton, which lure the squid to the surface to feed. Since the 1990s, the most important areas for landings of Humboldt squid are Chile, Mexico, and Peru (122–297, 53–66 and 291–435 thousand tonnes, respectively, in the period 2005–2007).[22]

Humboldt squid are known for their speed in feasting on hooked fish, sharks, and squid, even from their own species and shoal.[23] Numerous accounts have the squid attacking fishermen and divers in the area.[24] Their colouring and aggressive reputation have earned them the nickname diablos rojos (red devils) from fishermen off the coast of Mexico, as they flash red and white when struggling with the fishermen.[25]

Humboldt squid and El Niño

Although Humboldt squid are generally found in the warm Pacific waters off the Mexican coast, recent years have shown an increase in northern migration. The large 1997-98 El Niño event triggered the first sightings of Humboldt squid in Monterey Bay.[2] Then, during the minor El Niño event of 2002, they returned to Monterey Bay in higher numbers and have been seen there year-round since then. Similar trends have been shown off the coasts of Washington, Oregon, and even Alaska, although there are no year-round Humboldt squid populations in these locations. This change in migration is suggested to be due to warming waters during El Niño events, but other factors, such as a decrease in upper trophic level predators that would compete with the squid for food, could be impacting the migration shift, as well.[2]

Humboldt squid and ocean acidification

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that by the end of this century, ocean acidification will lower the Humboldt squid's metabolic rate by 31% and activity levels by 45%. This will lead the squid to have to retreat to shallower waters, where they can take up oxygen at higher levels.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ "Humboldt squid Found in Pebble Beach (2003)". Sanctuary Integrated Monitoring Network. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Zeidberg, L. & B.H. Robinson 2007. Invasive range expansion by the Humboldt squid, Dosidicus gigas, in the eastern North Pacific. PNAS 104(31): 12948–12950.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Curious Case of the Cannibal squid, Michael Tennesen, National Wildlife Magazine, Dec/Jan 2005, vol. 43 no. 1.

- ↑ Squid Sensitivity Discover Magazine April, 2003

- ↑ Jumbo squid invade San Diego shores, spook divers, Associated Press, July 17, 2009

- ↑ Zimmerman, Tim (December 2, 2010). "It's Hard Out Here for a Shrimp". Outside Online. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ Gilly, W.F., U. Markaida, C.H. Baxter, B.A. Block, A. Boustany, L. Zeidberg, K. Reisenbichler, B. Robison, G. Bazzino & C. Salinas 2006. Vertical and horizontal migrations by the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas revealed by electronic tagging. PDF Marine Ecology Progress Series 324: 1–17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nigmatullin, C.M., K.N. Nesis & A.I. Arkhipkin 2001. A review of the biology of the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae). Fisheries Research 54(1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00371-X

- ↑ Glaubrecht, M. & M.A. Salcedo-Vargas 2004. The Humboldt squid Dosidicus gigas (Orbigny, 1835): history of the Berlin specimen, with a reappraisal of other (bathy-)pelagic gigantic cephalopods (Mollusca, Ommastrephidae, Architeuthidae). Zoosystematics and Evolution 80(1): 53–69. doi:10.1002/mmnz.20040800105

- ↑ Norman, M.D. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Teuthis, Archie (June 1, 2011). "KRAKEN Day: Humboldts, They’re Here to Stay and They’re NOT Giant Squid". Deep Sea News. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ↑ "Giant squid caught in West Seattle", KING-TV, August 15, 2009

- ↑ Blumenthal, Les (April 27, 2008). "Aggressive eating machines spotted on our coast (2008)". The News Tribune. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ↑ "Jumbo Flying Squid Pile Up On Calif. Beach". 2012-12-11. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ "Video: Giant squid attacks diver". .nbc13.com. July 17, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Humboldt or Jumbo Squid Fact Sheet". Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Author Bio: Scott Cassell". deeperblue.net. ISSN 1469-865X. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ↑ Cassell, Scott (December 15, 2005). "Dancing with Demons". deeperblue.net. ISSN 1469-865X. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ↑ Roger T Hanlon, John B Messinger, Cephalopod Behavior, p. 56, Cambridge University Press, 1996

- ↑ Helena Smith (June 5, 2012). "Coordinated Hunting in Red Devils". Deep Sea News. Archived from the original on 2012-06-06. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ Posted July 31, 2007 (July 31, 2007). "The new squids in town | Kate Wing's Blog | Switchboard". National Resources Defense Council. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ Liu, B., X. Chen, H. Lu, Y. Chen & W. Qian 2010. Fishery biology of the jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas off the Exclusive Economic Zone of Chilean waters. Scientia Marina 74(4): 687–695. doi:10.3989/scimar.2010.74n4687

- ↑ Tennesen, Michael (December 1, 2004). "The Curious Case of the Cannibal Squid". National Wildlife Federation. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Pete (March 26, 2007). "Warning lights of the sea". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ Floyd, Mark (June 13, 2008). "Scientists See Squid Attack Squid". LiveScience. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ Rosa, Rui, and Brad A. Seibel. (2008) Synergistic effects of climate-related variables suggest future physiological impairment in a top oceanic predator. PNAS 105: 20776-0780

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Humboldt squid. |

- "CephBase: Humboldt squid". Archived from the original on 2005.

- Sea Wolves' presentation on Humboldt squid's physiology and behavior

- National Geographic: Humboldt squid

- LA Times: Jumbo squid

- KQED Humboldt squid broadcast

- Aggressive Eating Machines, The NewsTribune.com, Tacoma, WA

- Google Techtalk by Scott Cassell on Humboldt squid

- BELOW:2013 Humboldt squid fiction novel