Human trafficking

| Slavery |

|---|

| Contemporary |

| Types |

| Historic |

| By country or region |

| Religion |

| Opposition and resistance |

| Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against men |

|---|

| Issues |

|

| Other |

Human trafficking is the trade in humans, most commonly for the purpose of sexual slavery, forced labor or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others,[3][4] or for the extraction of organs or tissues,[5][6] including surrogacy and ova removal.[7] Human trafficking can occur within a country or trans-nationally. Human trafficking is a crime against the person because of the violation of the victim's rights of movement through coercion and because of their commercial exploitation. Human trafficking is the trade in people, and does not necessarily involve the movement of the person to another location.

Human trafficking represents an estimated $32 billion of international trade per annum, of the illegal international trade estimated at $650 billion per annum in 2010.[8]

Human trafficking is condemned as a violation of human rights by international conventions. In addition, human trafficking is subject to a directive in the European Union.[9]

Overview

Although it can occur at local levels, human trafficking has transnational implications, as recognized by the United Nations in the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (also referred to as the Trafficking Protocol), an international agreement under the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (CTOC) which entered into force on 25 December 2003. The protocol is one of three which supplement the CTOC.[10] The Trafficking Protocol is the first global, legally binding instrument on trafficking in over half a century, and the only one with an agreed-upon definition of trafficking in persons. One of its purposes is to facilitate international cooperation in investigating and prosecuting such trafficking. Another is to protect and assist human trafficking's victims with full respect for their rights as established in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Trafficking Protocol defines human trafficking as

(a) [...] the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs;

(b) The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) have been used;

(c) The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered “trafficking in persons” even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article;

(d) “Child” shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.[11]

The Trafficking Protocol was adopted by the United Nations in Palermo in 2000 and entered into force on 25 December 2003. As of March 2013 it has been signed by 117 countries and ratified by 154 parties.[12]

In 2004, the total annual revenue for trafficking in persons were estimated to be between USD$5 billion and $9 billion.[13]

In 2005, Patrick Belser of ILO estimated a global annual profit of $31.6 billion.[14] In 2008, the United Nations estimated nearly 2.5 million people from 127 different countries are being trafficked into 137 countries around the world.[15]

As of 2013, the U.S. government estimates that at any given time, approximately 27 million men, women, and children may be victims of human trafficking (Seelke 1) and within that 27 million, 18,000 people from over 50 countries are trafficked into the United States every year and over 300,000 children are trafficked within the U.S. annually.

Definition and usage

Human trafficking differs from people smuggling, which involves a person voluntarily requesting or hiring another individual to covertly transport them across an international border, usually because the smuggled person would be denied entry into a country by legal channels. Though illegal, there may be no deception or coercion involved. After entry into the country and arrival at their ultimate destination, the smuggled person is usually free to find their own way.

According to the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), people smuggling is a crime against the State due to the violation of national immigration laws, and does not require violations of the rights of the smuggled person. Human trafficking, on the other hand, is a crime against a person because of the violation of the victim's rights through coercion and exploitation.[16]

While smuggling requires travel, trafficking does not. Much of the confusion rests with the term itself, as the word "trafficking" evokes the idea of transport or travel. However, unlike most cases of people smuggling, victims of human trafficking are not permitted to leave upon arrival at their destination. They are held against their will through acts of coercion, and forced to work for or provide services to the trafficker or others. The work or services may include anything from bonded or forced labor to commercial sexual exploitation.[3][4] The arrangement may be structured as a work contract, but with no or low payment, or on terms which are highly exploitative. Sometimes the arrangement is structured as debt bondage, with the victim not being permitted or able to pay off the debt.

Bonded labor, or debt bondage, is probably the least known form of labor trafficking today, and yet it is the most widely used method of enslaving people. Victims become "bonded" when their labor is demanded as a means of repayment for a loan or service in which its terms and conditions have not been defined or in which the value of the victims’ services is not applied toward the liquidation of the debt. Generally, the value of their work is greater than the original sum of money "borrowed."[17]

Forced labor is a situation in which victims are forced to work against their own will under the threat of violence or some other form of punishment; their freedom is restricted and a degree of ownership is exerted. Men are at risk of being trafficked for unskilled work, which globally generates 31 billion USD according to the International Labor Organization.[18] Forms of forced labor can include domestic servitude, agricultural labor, sweatshop factory labor, janitorial, food service and other service industry labor, and begging.[17] Some of the products produced by forced labor are: clothing, cocoa, bricks, coffee, cotton, and gold, among others.[19]

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), the single largest global provider of services to victims of trafficking, reports receiving an increasing number of cases in which victims of trafficked were subjected to forced labour. A 2012 study observes that “…2010 was particularly notable as the first year in which IOM assisted more victims of labour trafficking than those who had been trafficked for purposes of sexual exploitation.”[20]

Child labour is a form of work that is likely to be hazardous to the physical, mental, spiritual, moral, or social development of children and can interfere with their education. The International Labor Organization estimates worldwide that there are 246 million exploited children aged between 5 and 17 involved in debt bondage, forced recruitment for armed conflict, prostitution, pornography, the illegal drug trade, the illegal arms trade, and other illicit activities around the world.June 2012

General

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has further assisted many non-governmental organizations in their fight against human trafficking. The 2006 armed conflict in Lebanon, which saw 300,000 domestic workers from Sri Lanka, Ethiopia and the Philippines jobless and targets of traffickers, led to an emergency information campaign with NGO Caritas Migrant to raise human-trafficking awareness. Additionally, an April 2006 report, Trafficking in Persons: Global Patterns, helped to identify 127 countries of origin, 98 transit countries and 137 destination countries for human trafficking. To date, it is the second most frequently downloaded UNODC report. Continuing into 2007, UNODC supported initiatives like the Community Vigilance project along the border between India and Nepal, as well as provided subsidy for NGO trafficking prevention campaigns in Bosnia, Croatia, and Herzegovina.[21] Public service announcements have also proved useful for organizations combating human trafficking. In addition to many other endeavors, UNODC works to broadcast these announcements on local television and radio stations across the world. By providing regular access to information regarding human-trafficking, individuals are educated how to protect themselves and their families from being exploited.

The United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN.GIFT) was conceived to promote the global fight on human trafficking, on the basis of international agreements reached at the UN. UN.GIFT was launched in March 2007 by UNODC with a grant made on behalf of the United Arab Emirates. It is managed in cooperation with the International Labour Organization (ILO); the International Organization for Migration (IOM); the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF); the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR); and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

Within UN.GIFT, UNODC launched a research exercise to gather primary data on national responses to trafficking in persons worldwide. This exercise resulted in the publication of the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons in February 2009. The report gathers official information for 155 countries and territories in the areas of legal and institutional framework, criminal justice response and victim assistance services.[21] UN.GIFT works with all stakeholders — governments, business, academia, civil society and the media — to support each other's work, create new partnerships, and develop effective tools to fight human trafficking.

The Global Initiative is based on a simple principle: human trafficking is a crime of such magnitude and atrocity that it cannot be dealt with successfully by any government alone. This global problem requires a global, multi-stakeholder strategy that builds on national efforts throughout the world. To pave the way for this strategy, stakeholders must coordinate efforts already underway, increase knowledge and awareness, provide technical assistance, promote effective rights-based responses, build capacity of state and non-state stakeholders, foster partnerships for joint action, and above all, ensure that everybody takes responsibility for this fight. By encouraging and facilitating cooperation and coordination, UN.GIFT aims to create synergies among the anti-trafficking activities of UN agencies, international organizations and other stakeholders to develop the most efficient and cost-effective tools and good practices.[22]

UN.GIFT aims to mobilize state and non-state actors to eradicate human trafficking by reducing both the vulnerability of potential victims and the demand for exploitation in all its forms, ensuring adequate protection and support to those who fall victim, and supporting the efficient prosecution of the criminals involved, while respecting the fundamental human rights of all persons. In carrying out its mission, UN.GIFT will increase the knowledge and awareness on human trafficking, promote effective rights-based responses, build capacity of state and non-state actors, and foster partnerships for joint action against human trafficking. For more information view the UN.GIFT Progress Report 2009.[22][23]

Further UNODC efforts to motivate action launched the Blue Heart Campaign Against Human Trafficking on March 6, 2009,[24] which Mexico launched its own national version of in April 2010.[25][26] The campaign encourages people to show solidarity with human trafficking victims by wearing the blue heart, similar to how wearing the red ribbon promotes transnational HIV/AIDS awareness.[27] On November 4, 2010, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon launched the United Nations Voluntary Trust Fund for Victims of Trafficking in Persons to provide humanitarian, legal and financial aid to victims of human trafficking with the aim of increasing the number of those rescued and supported, and broadening the extent of assistance they receive.[28]

In December 2012, UNODC published the new edition of the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons.[29] The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2012 has revealed that 27 per cent of all victims of human trafficking officially detected globally between 2007 and 2010 are children, up 7 per cent from the period 2003 to 2006.

The Global Report recorded victims of 136 different nationalities detected in 118 countries between 2007 and 2010, during which period, 460 different flows were identified. Around half of all trafficking took place within the same region with 27 per cent occurring within national borders. One exception is the Middle East, where most detected victims are East and South Asians. Trafficking victims from East Asia have been detected in more than 60 countries, making them the most geographically dispersed group around the world. There are significant regional differences in the detected forms of exploitation. Countries in Africa and in Asia generally intercept more cases of trafficking for forced labour, while sexual exploitation is somewhat more frequently found in Europe and in the Americas. Additionally, trafficking for organ removal was detected in 16 countries around the world.The Report raises concerns about low conviction rates - 16 per cent of reporting countries did not record a single conviction for trafficking in persons between 2007 and 2010. On a positive note, 154 countries have ratified the United Nations Trafficking in Persons Protocol, of which UNODC is the guardian. Significant progress has been made in terms of legislation, as 83 per cent of countries now have a law that criminalizes trafficking in persons in accordance with the Protocol.[30]

Current international treaties (general)

- Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, entered into force in 1957,

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children; and

- Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.

- ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29)

- ILO Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105)

- ILO Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138)

- ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)

United States

In 2002, Derek Ellerman and Katherine Chon founded a non-government organization called Polaris Project to combat human trafficking. In 2007, Polaris instituted the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) where[31] callers can report tips and receive information on human trafficking.[32] Polaris' website and hotline informs the public about where cases of suspected human trafficking have occurred within the United States. The website records calls on a map.[33]

In 2007 the U.S. Senate designated January 11 as a National Day of Human Trafficking Awareness in an effort to raise consciousness about this global, national and local issue. In 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013, President Barack Obama proclaimed January as National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month.[34]

Council of Europe

On 3 May 2005, the Committee of Ministers adopted the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS No. 197).[35] The Convention was opened for signature in Warsaw on 16 May 2005 on the occasion of the 3rd Summit of Heads of State and Government of the Council of Europe. On 24 October 2007, the Convention received its tenth ratification thereby triggering the process whereby it entered into force on 1 February 2008. The Convention now counts 39 ratifications by Council of Europe member states, with an additional four member states having signed but not yet ratified.

While other international instruments already exist in this field, the Council of Europe Convention, the first European treaty in this field, is a comprehensive treaty focusing mainly on the protection of victims of trafficking and the safeguard of their rights. It also aims to prevent trafficking and to prosecute traffickers. In addition, the Convention provides for the setting up of an effective and independent monitoring mechanism capable of controlling the implementation of the obligations contained in the Convention.

The Convention is not restricted to Council of Europe member states; non-member states and the European Union also have the possibility of becoming Party to the Convention.

The Convention established a Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA) which monitors the implementation of the Convention through country reports. As of 1 March 2013, GRETA has published 17 country reports.[36]

In addition, the European Court of Human Rights of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg has passed judgments concerning trafficking in human beings which violated obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights: Siliadin v. France,[37] judgment of 26 July 2005, and Rantsev v. Cyprus and Russia,[38] judgment of 7 January 2010.

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

In 2003 the OSCE established an anti-trafficking mechanism aimed at raising public awareness of the problem and building the political will within participating States to tackle it effectively.

The OSCE actions against human trafficking are coordinated by the Office of the Special Representative for Combating the Traffic of Human Beings.[39] In January 2010, Maria Grazia Giammarinaro became the OSCE Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings. Dr. Giammarinaro (Italy) has been a judge at the Criminal Court of Rome since 1991. She served from 2006 until 2009 in the European Commission's Directorate-General for Justice, Freedom and Security in Brussels, where she was responsible for work to combat human trafficking and sexual exploitation of children, as well as for penal aspects of illegal immigration within the unit dealing with the fight against organized crime. During this time, she co-ordinated the Group of Experts on Trafficking in Human Beings of the European Commission. From 2001 to 2006 she was a judge for preliminary investigation in the Criminal Court of Rome. Prior to that, from 1996 she was Head of the Legislative Office and Adviser to the Minister for Equal Opportunities. From 2006 to December 2009 the office was headed by Eva Biaudet, a former Member of Parliament and Minister of Health and Social Services in her native Finland.

The activities of the Office of the Special Representative range from training law enforcement agencies to tackle human trafficking to promoting policies aimed at rooting out corruption and organised crime. The Special Representative also visits countries and can, on their request, support the formation and implementation of their anti-trafficking policies. In other cases the Special Representative provides advice regarding implementation of the decisions on human trafficking, and assists governments, ministers and officials to achieve their stated goals of tackling human trafficking.

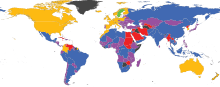

The Anti-trafficking Policy Index

The '3P Anti-trafficking Policy Index' measures the effectiveness of government policies to fight human trafficking based on an evaluation of policy requirements prescribed by the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (2000).[40]

The policy level is evaluated using a five-point scale, where a score of five indicates the best policy practice, while score 1 is the worst. This scale is used to analyze the main three anti-trafficking policy areas: (i) prosecuting (criminalizing) traffickers, (ii) protecting victims, and (iii) preventing the crime of human trafficking. Each sub-index of prosecution, protection and prevention is aggregated to the overall index with an unweighted sum, with the overall index ranging from a score of 3 (worst) to 15 (best). It is available for up to 177 countries over the 2000-2009 period (on an annual basis).

The outcome of the Index shows that anti-trafficking policy has overall improved over the 2000-2009 period. Improvement is most prevalent in the prosecution and prevention areas worldwide. An exception is protection policy, which shows a modest deterioration in recent years.

In 2009 (the most recent year of the evaluation), seven countries demonstrate the highest possible performance in policies for all three dimensions (overall score 15). These countries are Germany, Australia, the Netherlands, Italy, Belgium, Sweden and the US. The second best performing group (overall score 14) consists of France, Norway, South Korea, Croatia, Canada, Austria, Slovenia and Nigeria. The worst performing country in 2009 was North Korea, receiving the lowest score in all dimensions (overall score 3), followed by Somalia. For more information view the Human Trafficking Research and Measurement website.[41]

Trafficking of children

Trafficking of children involves the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of children for the purpose of exploitation. The commercial sexual exploitation of children can take many forms, including forcing a child into prostitution[42][43] or other forms of sexual activity or child pornography. Child exploitation may also involve forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude, the removal of organs, illicit international adoption, trafficking for early marriage, recruitment as child soldiers, for use in begging or as athletes (such as child camel jockeys or football players), or for recruitment for cults.[44]

IOM statistics indicate that a significant minority (35%) of trafficked persons it assisted in 2011 were less than 18 years of age, which is roughly consistent with estimates from previous years. It was reported in 2010 that Thailand and Brazil were considered to have the worst child sex trafficking records.[45]

Traffickers in children may take advantage of the parents' extreme poverty. Parents may sell children to traffickers in order to pay off debts or gain income, or they may be deceived concerning the prospects of training and a better life for their children. They may sell their children into labor, sex trafficking, or illegal adoptions.

The adoption process, legal and illegal, when abused can sometimes result in cases of trafficking of babies and pregnant women from developing countries to the West.[46] In David M. Smolin’s papers on child trafficking and adoption scandals between India and the United States,[47][48] he presents the systemic vulnerabilities in the inter-country adoption system that makes adoption scandals predictable.

Sex trafficking

There is no universally accepted definition of trafficking for sexual exploitation. The term was formerly thought of as the organized movement of people, usually women, between countries and within countries for sex work with the use of physical coercion, deception and bondage through forced debt. However, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (USA),[49] does not require movement for the offence. The issue becomes contentious when the element of coercion is removed from the definition to incorporate facilitating the willing involvement in prostitution. For example, in the United Kingdom, The Sexual Offenses Act 2003 incorporated trafficking for sexual exploitation but did not require those committing the offence to use coercion, deception or force, so that it also includes any person who enters the UK to carry out sex work with consent as having been trafficked.[50] In addition, any minor involved in a commercial sex act in the United States while under the age of 18 qualifies as a trafficking victim, even if no force, fraud or coercion is involved, under the definition of Severe Forms of Trafficking in Persons, in the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000.[49]

Sexual trafficking includes coercing a migrant into a sexual act as a condition of allowing or arranging the migration. Sexual trafficking uses physical or sexual coercion, deception, abuse of power and bondage incurred through forced debt. Trafficked women and children, for instance, are often promised work in the domestic or service industry, but instead are sometimes taken to brothels where they are used in Sex worker, with their passports and other identification papers confiscated. They may be beaten or locked up and promised their freedom only after earning – through prostitution – their purchase price, as well as their travel and visa costs.[51][52]

The Yogyakarta Principles, a document on international human rights law on sexual orientation and gender identity, also affirms that "States shall (c) establish legal, educational and social measures, service and programs to address factors that increase vulnerability to trafficking, sale and all forms of exploitation, including but not limited to sexual exploitation, on the grounds of actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity, including such factors as social exclusion, discrimination, rejection by families or cultural communities, lack of financial independence, homelessness, discriminatory social attitudes leading to low self-esteem, and lack of protection from discrimination in access to housing accommodation, employment and social services.[53]

Sex trafficking victims are generally found in dire circumstances and easily targeted by traffickers. Individuals, circumstances, and situations vulnerable to traffickers include homeless individuals, runaway teens, displaced homemakers, refugees, job seekers, tourists, kidnap victims and drug addicts. While it may seem like trafficked people are the most vulnerable and powerless minorities in a region, victims are consistently exploited from any ethnic and social background.[54]

Traffickers, also known as pimps or madams, exploit vulnerabilities and lack of opportunities, while offering promises of marriage, employment, education, and/or an overall better life. However, in the end, traffickers force the victims to become prostitutes or work in the sex industry[54] Various work in the sex industry includes prostitution, dancing in strip clubs, performing in pornographic films and pornography, and forms of involuntary servitude. Underage sex trafficking victims in the U.S. are often runaways, troubled, and homeless youth.[55]

Human trafficking does not require travel or transport from one location to another, but one form of sex trafficking involves international agents and brokers who arrange travel and job placements for women from one country. Women are lured to accompany traffickers based on promises of lucrative opportunities unachievable in their native country. However, once they reach their destination, the women discover that they have been deceived and learn the true nature of the work that they will be expected to do. Most have been told false information regarding the financial arrangements and conditions of their employment and find themselves in coercive or abusive situations from which escape is both difficult and dangerous.[56] According to a 2009 U.S. Department of Justice report, there were 1,229 suspected human trafficking incidents in the United States from January 2007- September 2008. Of these, 83 percent were sex trafficking cases, though only 9% of all cases could be confirmed as examples of human trafficking.[57]

Profile and modus operandi of traffickers

Traffickers of young girls into prostitution in India are often women who have been trafficked themselves. As adults they use personal relationships and trust in their villages of origin to recruit additional girls.[58]

In some cases, traffickers approach very vulnerable women (including underage girls) to offer them "legitimate" work or the promise of an opportunity for education. The main types of work offered are in the catering and hotel industry, in bars and clubs, modeling contracts, or au pair work. Traffickers sometimes use offers of marriage, threats, intimidation, and kidnapping as means of obtaining victims. In many cases, the women end up trafficked into the sex industry. Also, some (migrating) prostitutes (See: migrant sex work) can become victims of human trafficking because the women know they will be working as prostitutes, but they are led to have an inaccurate view of the circumstances and the conditions of the work in their country of destination, and consequently get exploited.[59][60]

In order to obtain control over their victims, traffickers will use force, drugs, emotional tactics and financial methods. On occasion, they will even resort to various forms of violence, such as gang rape and mental and physical abuse. Sometimes, the victims will succumb to Stockholm Syndrome because their captors will pretend to "love" and "need" them, even going so far as promise marriage and future stability. This is particularly effective with younger victims, because they are more inexperienced and therefore easily manipulated.[61]

Profile of victims

The main motive of a woman (in some cases, an underage girl) to accept an offer from a trafficker is better financial opportunities for herself or her family. A study on the origin countries of trafficking confirms that most trafficking victims are not the poorest in their countries of origin, and sex trafficking victims are likely to be women from countries with some freedom to travel alone and some economic freedom.[62]

Combating sex trafficking

International institutions and legislation

History of international legislation

International pressure to address trafficking in women and children became a growing part of the social Reform movement in the United States and Europe during the late 19th century. International legislation against the trafficking of women and children began with the conclusion of an international convention in 1901, followed by conclusion of the International Agreement for the suppression of the White Slave Traffic in 1904. (The latter was revised in 1910.) These conventions were ratified by 34 countries. The first formal international research into the scope of the problem was funded by American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, through the American Bureau of Social Hygiene. In 1923, a committee from the bureau was tasked with investigating trafficking in 28 countries, interviewing approximately 5,000 informants and analyzing information over two years before issuing its final report. This was the first formal report on trafficking in women and children to be issued by an official body.[63]

The League of Nations, formed in 1919, took over as the international coordinator of legislation intended to end the trafficking of women and children. An international Conference on White Slave Traffic was held in 1921, attended by the 34 countries that ratified the 1901 and 1904 conventions.[64] Another convention against trafficking was ratified by League members in 1922, and like the 1904 international convention, this one required ratifying countries to submit annual reports on their progress in tackling the problem. Compliance with this requirement was not complete, although it gradually improved: in 1924, approximately 34% of the member countries submitted reports as required, which rose to 46% in 1929, 52% in 1933, and 61% in 1934.[65] The 1921 International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children was sponsored by the League of Nations.

United Nations

In 1949, the first international protocol dealing with sex slavery was the 1949 UN Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and Exploitation of Prostitution of Others.[66] This convention followed the abolitionist idea of sex trafficking as incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person. Serving as a model for future legislation, the 1949 UN Convention was not ratified by every country, but came into force in 1951. These early efforts led to the 2000 Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, mentioned above. These instruments contain the elements of the current international law on trafficking in humans.

In 2011, the United Nations reported that girl victims made up two thirds of all trafficked children. Girls constituted 15 to 20 per cent of the total number of all detected victims, including adults, whereas boys comprised about 10 per cent, said the Report, which was based on official data supplied by 132 countries.[67]

Current international treaties include the Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriages, entered into force in 1964.

In the United States

Up until the early 1960s, when racism was a major issue in the US, Congress was concerned about White slavery. The result of this fear was the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910 (better known as the Mann Act), which criminalized interracial marriage and banned single women from crossing state borders for morally wrong acts. In 1914, of the women arrested for crossing state borders under this act, 70% were charged with voluntary prostitution. Once the idea of a sex slave shifted from a White woman to an enslaved woman from countries in poverty, the US began passing immigration acts to curtail aliens from entering the country among other reasons. Several acts such as the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924 were passed to prevent emigrants from Europe and Asia from entering the United States. Following the banning of immigrants during the 1920s, human trafficking was not seen as a major issue until the 1990s.[68][69]

At 18 U.S.C. § 1591, or the Commercial Sex Act, the US makes it illegal to recruit, entice, obtain, provide, move or harbor a person or to benefit from such activities knowing that the person will be caused to engage in commercial sex acts where the person is under 18 or where force, fraud or coercion exists.[70][71]

Under the Bush Administration, fighting sex slavery worldwide and domestically became a priority with an average of $100 million spent per year, which substantially outnumbers the amount spent by other countries. Before President Bush took office, Congress had passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA). The TVPA strengthened services to victims of violence, law enforcements ability to reduce violence against women and children, and education against human trafficking. Also specified in the TVPA was a mandate to collect funds for the treatment of sex trafficking victims that provided shelter, food, education, and financial grants. Internationally, the TVPA set standards that governments of other countries must follow in order to receive aid from the U.S. to fight human trafficking. Once George W. Bush took office in 2001, restricting sex trafficking became one of his primary humanitarian efforts. The Attorney General under President Bush, John Ashcroft, strongly enforced the TVPA. The Act was subsequently renewed in 2004, 2006, and 2008. It established two stipulations an applicant has to meet in order to receive the benefits of a T-Visa. First, a trafficked victim must prove/admit to being trafficked and second must submit to prosecution of his or her trafficker. In 2011, Congress failed to re-authorize the Act. The State Department publishes an annual Trafficking in Persons Report, which examines the progress that the U.S. and other countries have made in destroying human trafficking businesses, arresting the kingpins, and rescuing the victims.[72][73]

Council of Europe

Complementary protection is ensured through the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (Lanzarote, 25 October 2007).

Other government actions

Actions taken to combat human trafficking vary from government to government.[74] Some government actions include

- introducing legislation specifically aimed at criminalizing human trafficking

- developing co-operation between law enforcement agencies and non-government organizations (NGOs) of numerous nations

- raising awareness of the issue

Raising awareness can take three forms. First, governments can raise awareness amongst potential victims, particularly in countries where human traffickers are active. Second, they can raise awareness amongst the police, social welfare workers and immigration officers to equip them to deal appropriately with the problem. And finally, in countries where prostitution is legal or semi-legal, they can raise awareness amongst the clients of prostitution so that they can watch for signs of human trafficking victims. Methods to raise general awareness often include television programs, documentary films, internet communications, and posters.[75] and posters.[76]

Many countries have come under criticism for inaction, or ineffective action. Criticisms include the failure of governments to properly identify and protect trafficking victims, enactment of immigration policies which potentially re-victimize trafficking victims, and insufficient action in helping prevent vulnerable populations from becoming trafficking victims. A particular criticism has been the reluctance of some countries to tackle trafficking for purposes other than sex.

Non Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

Many NGOs work on the issue of sex trafficking. One major NGO is the International Justice Mission (IJM). IJM is a U.S.-based non-profit human rights organization that combats human trafficking in developing countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. IJM states that it is a “human rights agency that brings rescue to victims of slavery, sexual exploitation, and other forms of violent oppression.” It is a faith-based organization since its purported goal is to “restore to victims of oppression the things that God intends for them: their lives, their liberty, their dignity, the fruits of their labor.”[77] The IJM receives over $900,000 from the U.S. government.[78] The organization has two methods for rescuing victims: brothel raids in cooperation with local police, and "buy bust" operations in which undercover agencies pretend to purchase sex services of an underage girl. After the raid and rescue, the women are sent to rehabilitation programs run by NGOs (such as churches) or the government. Extensive evidence suggest that rehabilitation programs may be ineffective, very harmful, and jail-like. NGOs find that the women experience high rates of violence in rehabilitation and afterwards they are likely to return to sex work with no alternative employment opportunities available.[77]

Campaigns and initiatives

The Demi and Ashton (DNA) Foundation was created by celebrity humanitarians Demi Moore and Ashton Kutcher in 2009 in their efforts to fight human trafficking (specifically focusing on sex trafficking of children) in the U.S. In September 2010, the pair announced the launch of their “Real Men Don't Buy Girls” campaign to combat child sex trafficking alongside other Hollywood stars and technology companies like Microsoft, Twitter, and Facebook. "Real Men Don't Buy Girls" is based on the idea that high-profile men speaking out against child sex trafficking can help reduce the demand for young girls in the commercial sex trade. A press conference was held on September 23 at the Clinton Global Initiative.[79] In 1994 Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women was established to combat trafficking in women in any grounds. In addition to campaigns led by high profile celebrities, the popular TV channel MTV started a campaign of their own to combat sex trafficking.[citation needed] The initiative called “MTV Exit” joined forces with Facebook to raise awareness in South Asia. MTV had hopes of educating young girls about sex trafficking via social media. The purpose of the campaign was to not only raise awareness but also to educate young women on human trafficking.[citation needed] Young children, and often women who come from countries that are not as advanced and developed as the United States, are in most cases more susceptible to be victims of this particular crime.[citation needed] The Internet may provide a line of communication when no other means of communication are available between countries.

While globalization fostered new technologies that may exacerbate sex trafficking, technology can also be used to assist law enforcement and anti-trafficking efforts. A study was done on online classified ads surrounding the Super Bowl. A number of reports have noticed increase in sex trafficking during previous years of the Super Bowl.[80] For the 2011 Super Bowl held in Dallas, Texas, the Back page for Dallas area experienced a 136% increase on the number of posts in the Adult section on Super Bowl Sunday, where as Sundays typically have the lowest amount of posts. Researchers analyzed the most salient terms in these online ads, which suggested that many escorts were traveling across state lines to Dallas specifically for the Super Bowl, and found that the self-reported ages were higher than usual. Twitter was another social networking platform studied for detecting sex trafficking. Digital tools can be used to narrow the pool of sex trafficking cases, albeit imperfectly and with uncertainty.[81]

'End Demand'

End Demand refers to the strategy and efforts of different institutions that seek to end sex trafficking by eliminating and criminalizing the demand for commercial sex. End Demand is very popular in some countries including the United States and Canada.[82] Proponents of the end demand strategy support initiatives such as "John's schools" that rehabilitate johns, increased arrests of johns, and public shaming (e.g. billboards and websites that publicly name johns who were caught).[82][83] John's Schools were pioneered in San Francisco in 1995 and now used in many cities across the U.S. as well as other countries such as the UK and Canada. Some compare John's Schools programs to driver's safety courses, because first offenders can pay a fee to attend class(es) on the harms of prostitution, and upon completion, the charges against the john will be dropped. Another initiative that seeks to end demand is the cross-country tour "Ignite the Road to Justice," launched by the 2011 Miss Canada, Tara Teng. Teng's initiative circulates a petition to end the demand for commercial sex that drives prostitution and sex trafficking. End Demand efforts also include large-scale public awareness campaigns. Campaigns have started in Sweden, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Atlanta, Georgia. The Atlanta campaign in 2006 was titled "Dear John," and ran ads in local media reaching out to potential johns to discourage them from buying sex. Massachusetts and Rhode Island also had legislative efforts that criminalized prostitution and increased end demand efforts by targeting johns.[82]

Sweden criminalized the buying of sex in 1999, and Norway and Iceland have later introduced similar laws. The laws were aimed at combating trafficking.[84] Iceland also banned strip clubs in 2010.

Measures of human trafficking and efforts

There are many different estimates of how large the human trafficking and sex trafficking industries are. According to scholar Kevin Bales, author of Disposable People (2004), estimates that as many as 27 million people are in "modern-day slavery" across the globe.[85][86] In 2008, the U.S. Department of State estimates that 2 million children are exploited by the global commercial sex trade.[87] In the same year, a study classified 12.3 million individuals worldwide as “forced laborers, bonded laborers or sex-trafficking victims.” Approximately 1.39 million of these individuals worked as commercial sex slaves, with women and girls comprising 98%, or 1.36 million, of this population.[88]

The enactment of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000 by the United States Congress and its subsequent re-authorizations established the Department of State's Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, which engages with foreign governments to fight human trafficking and publishes a Trafficking in Persons Report annually. The Trafficking in Persons Report evaluates each country's progress in anti-trafficking and places each country onto one of three tiers based on their governments' efforts to comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking as prescribed by the TVPA.[89]

In particular, there were three main components of the TVPA, commonly called the three P’s: PROTECTION: The TVPA increased the U.S. Government’s efforts to protect trafficked foreign national victims including, but not limited to: Victims of trafficking, many of whom were previously ineligible for government assistance, were provided assistance; and a non-immigrant status for victims of trafficking if they cooperated in the investigation and prosecution of traffickers (T-Visas, as well as providing other mechanisms to ensure the continued presence of victims to assist in such investigations and prosecutions). PROSECUTION: The TVPA authorized the U.S. Government to strengthen efforts to prosecute traffickers including, but not limited to: Creating a series of new crimes on trafficking, forced labor, and document servitude that supplemented existing limited crimes related to slavery and involuntary servitude; and recognizing that modern-day slavery takes place in the context of fraud and coercion, as well as force, and is based on new clear definitions for both trafficking into sexual exploitation and labor exploitation: Sex trafficking was defined as, “a commercial sex act that is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age. Labor trafficking was defined as, “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery. PREVENTION: The TVPA allowed for increased prevention measures including, but not limited to: Authorizing the U.S. Government to assist foreign countries with their efforts to combat trafficking, as well as address trafficking within the United States, including through research and awareness-raising; and providing foreign countries with assistance in drafting laws to prosecute trafficking, creating programs for trafficking victims, and assistance with implementing effective means of investigation.[90]

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton later identified a fourth P, “partnership,” in 2009 to serve as a, “pathway to progress in the effort against modern-day slavery.”6

Structural factors

A complex set of factors fuel sex trafficking, including poverty, unemployment, social norms that discriminate against women, demand for commercial sex, institutional challenges, and globalization.

Poverty and globalization

Poverty and lack of educational and economic opportunities in one's hometown may lead women to voluntarily migrate and then be involuntarily trafficked into sex work.[82][91] As globalization opened up national borders to greater exchange of goods and capital, labor migration also increased. Less wealthy countries have fewer options for livable wages. The economic impact of globalization pushes people to make conscious decisions to migrate and be vulnerable to trafficking. Gender inequalities that hinder women from participating in the formal sector also push women into informal sectors.[92]

Long waiting lists for organs in the United States and Europe created a thriving international black market. Traffickers harvest organs, particularly kidneys, to sell for large profit and often without properly caring for or compensating the victims. Victims often come from poor, rural communities and see few other options than to sell organs illegally.[93] Wealthy countries' inability to meet organ demand within their own borders perpetuates trafficking. By reforming their internal donation system, Iran achieved a surplus of legal donors and provides an instructive model for eliminating both organ trafficking and -shortage.[94]

Globalization and the rise of internet technology has also facilitated sex trafficking. Online classified sites and social networks such as Craigslist have been under intense scrutiny for being used by johns and traffickers in facilitating sex trafficking and sex work in general. Traffickers use explicit sites and underground sites (e.g. Craigslist, Backpage, MySpace) to market, recruit, sell, and exploit females. Facebook, Twitter, and other social networking sites are suspected for similar uses. For example, Randal G. Jennings was convicted of sex trafficking five underage girls by forcing them to advertise on Craigslist and driving them to meet the johns. According to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, online classified ads reduce the risks of finding prospective customers.[95] Studies have identified the internet as the single biggest facilitator of commercial sex trade, although it is difficult to ascertain which women advertised are sex trafficking victims.[96] Traffickers and pimps use the internet to recruit minors, since internet and social networking sites usage have significantly increased especially among children.[97]

Organized criminals can generate up to several thousand dollars per day from one trafficked girl, and the internet has further increased profitability of sex trafficking and child trafficking. With faster access to a wider clientele, more sexual encounters can be scheduled.[98] Victims and clients, according a New York City report on sex trafficking in minors, increasingly use the internet to meet customers. Due to protests, Craigslist has since closed its adult services section. According to authorities, Backpage is now the main source for advertising trafficking victims.[99] Investigators also frequently browse online classified ads to identify potential underage girls who are trafficked.

While globalization fostered new technologies that may exacerbate sex trafficking, technology can also be used to assist law enforcement and anti-trafficking efforts. A study was done on online classified ads surrounding the Super Bowl. A number of reports have noticed increase in sex trafficking during previous years of the Super Bowl.[80] For the 2011 Super Bowl held in Dallas, Texas, the Backpage for Dallas area experienced a 136% increase on the number of posts in the Adult section on Super Bowl Sunday, where as Sundays typically have the lowest amount of posts. Researchers analyzed the most salient terms in these online ads, which suggested that many escorts were traveling across state lines to Dallas specifically for the Super Bowl, and found that the self-reported ages were higher than usual. Twitter was another social networking platform studied for detecting sex trafficking. Digital tools can be used to narrow the pool of sex trafficking cases, albeit imperfectly and with uncertainty.[81]

However, there has been no evidence found actually linking the Super Bowl - or any other sporting event - to increased trafficking or prostitution.[100][101]

Political and institutional challenges

Corrupt and inadequately trained police officers can be complicit in sex trafficking and/or commit violence against sex workers, including sex trafficked victims.[102]

Anti-trafficking agendas from different groups can also be in conflict. In the movement for sex workers rights, sex workers establish unions and organizations, which seek to eliminate trafficking themselves. However, law enforcement also seek to eliminate trafficking and to prosecute trafficking, and their work may infringe on sex workers' rights and agency. For example, the sex workers union DMSC (Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee) in Kolkata, India, has "self-regulatory boards" (SRBs) that patrol the red light districts and assist girls who are underage or trafficked. The union opposes police intervention and interferes with police efforts to bring minor girls out of brothels, on the grounds that police action might have an adverse impact on non-trafficked sex workers, especially because police officers in many places are corrupt and violent in their operations.[102] Critics argue that since sex trafficking is an economic and violent crime, it calls for law enforcement to intervene and prevent violence against victims.

Criminalization of sex work also may foster the underground market for sex work and enable sex trafficking.[82]

Difficult political situations such as civil war and social conflict are push factors for migration and trafficking. A study reported that larger countries, the richest and the poorest countries, and countries with restricted press freedom are likely to engage in more sex trafficking. Specifically, being in a transitional economy made a country nineteen times more likely to be ranked in the highest trafficking category, and gender inequalities in a country's labor market also correlated with higher trafficking rates.[62]

An annual US State Department report in June 2013 cited Russia and China as among the worst offenders in combatting forced labour and sex trafficking, raising the possibility of US sanctions being leveraged against these countries.[103]

In 2013, the Supreme Court of Canada declared the laws which effectively prohibited prostitution illegal. It delayed the implementation of this ruling for one year to give the parliament time to enact replacement laws, if it so desired.[104]

Social norms

Women and girls are more prone to trafficking also because of social norms that marginalize their value and status in society. Females face considerable gender discrimination both at home and in school. Stereotypes that women belong at home in the private sphere and that women are less valuable because they do not and are not allowed to contribute to formal employment and monetary gains the same way men do further marginalize women's status relative to men. Some religious beliefs also lead people to believe that the birth of girls are a result of bad karma, further cementing the belief that girls are not as valuable as boys. Various social norms contribute to women's inferior position and lack of agency and knowledge, thus making them vulnerable to exploitation such as sex trafficking.[105]

Demand for commercial sex

Abolitionists who seek an end to sex trafficking explain the nature of sex trafficking as an economic supply and demand model. In this model, male demand for prostitutes leads to a market of sex work, which, in turn, fosters sex trafficking, the illegal trade and coercion of people into sex work, and pimps and traffickers become 'distributors' who supply people to be sexually exploited. The demand for sex trafficking can also be facilitated by some pimps' and traffickers' desire for women whom they can exploit as workers because they do not require wages, safe working circumstances, and agency in choosing customers.[82]

Consequences

Consequences for victims

Sex trafficking victims face threats of violence from many sources, including customers, pimps, brothel owners, madams, traffickers, and corrupt local law enforcement officials. Raids as an anti-sex trafficking measure severely impact sex trafficked victims. Due to their complicated legal status and their language barriers, the arrest or fear of arrest creates stress and other emotional trauma for trafficking victims. Victims may also experience physical violence from law enforcement during raids.[106][107]

Trafficking victims are also exposed to different psychological stressors. They suffer social alienation in the host and home countries. Stigmatization, social exclusion, and intolerance make reintegration into local communities difficult. The governments offer little assistance and social services to trafficked victims upon their return. As the victims are also pushed into drug trafficking, many of them face criminal sanctionoso.[108]

Economic impacts

According to estimates from the International Labour Organization (ILO), every year the human trafficking industry generates 32 billion USD, half of which ($15.5 billion) is made in industrialized countries, and a third of which ($9.7 billion) is made in Asia.[109] A 2011 paper published in Human Rights Review, “Sex Trafficking: Trends, Challenges and Limitations of International Law,” notes that, since 2000, the number of sex-trafficking victims has risen while costs associated with trafficking have declined: “Coupled with the fact that trafficked sex slaves are the single most profitable type of slave, costing on average $1,895 each but generating $29,210 annually, [there are] stark predictions about the likely growth in commercial sex slavery in the future.”[88] Sex trafficking victims rarely get a share of the money that they make through coerced sex work, which further keeps them oppressed.[110]

Popular culture

Criticism

Both the human trafficking discourse and the actions undertaken by the anti-human traffickers have been criticized by some scholars.[111][112] and journalists[113] The criticism touches upon three main themes: 1) statistics and data on human trafficking; 2) the concept itself; 3) the anti-trafficking measures.

Problems with statistics and data

Numerous NGOs and governmental agencies produce estimates and specific statistics on the numbers of potential and actual victims of trafficking.[114] According to the critics, these figures rarely have identifiable sources or transparent methodologies behind them and in most (if not all) instances, they are mere guesses.[115][116] Scholars argue that this is a result of the fact that it is impossible to produce any meaningful statistics on a reportedly illegal and covert phenomenon happening in the shadow economy.[111][117][118] Others argue that many of these statistics are inflated to aid advocacy of anti-trafficking NGOs and the anti-trafficking policies of governments. Due to the definition of trafficking as a process (not a singly defined act) and the fact that it is a dynamic phenomenon with constantly shifting patterns relating to economic circumstances, much of the statistical evaluation is flawed.[119]

Problems with the concept

According to some scholars, the very concept of human trafficking is murky and misleading.[111] It has been argued that while human trafficking is commonly seen as a monolithic crime, in reality it is an act of illegal migration that involves various different actions: some of them may be criminal or abusive, but others often involve consent and are legal.[111] Laura Agustin argues that not everything that might seem abusive or coercive is considered as such by the migrant. For instance, she states that: ‘would-be travellers commonly seek help from intermediaries who sell information, services and documents. When travellers cannot afford to buy these outright, they go into debt’.[117] One scholar says that while these debts might indeed be on very harsh conditions, they are usually incurred on a voluntary basis.[111]

The critics of the current approaches to trafficking say that a lot of the violence and exploitation faced by illegal migrants derives precisely from the fact that their migration and their work are illegal and not primarily because of some evil trafficking networks.[120] Tara McCormack believes that the whole trafficking discourse can actually be detrimental to the interests of migrants as it denies them agency and as it depoliticizes debates on migration.[121]

The international Save the Children organization also stated: "... The issue, however, gets mired in controversy and confusion when prostitution too is considered as a violation of the basic human rights of both adult women and minors, and equal to sexual exploitation per se. ... trafficking and prostitution become conflated with each other. .... On account of the historical conflation of trafficking and prostitution both legally and in popular understanding, an overwhelming degree of effort and interventions of anti-trafficking groups are concentrated on trafficking into prostitution."[122]

Some critics claim that NGOs involved in anti-sex trafficking often employ the 'politics of pity,' which promotes that all trafficked victims are completely guiltless, fully coerced into sex work, and experience the same degrees of physical suffering. One critic identifies two strategies that gain pity: denunciation - attributing all violence and suffering to the perpetrator - and sentiment - exclusively depicting the suffering of the women. NGOs' use of images of unidentifiable females suffering physically help display sex trafficking scenarios as all the same. However, critics point out that not all trafficking victims have been abducted, abused physically, and repeatedly raped, unlike popular portrayals.[123]

Problems with anti-trafficking measures

Groups like Amnesty International have been critical of insufficient or ineffective government measures to tackle human trafficking. Criticism includes a lack of understanding of human trafficking issues, poor identification of victims and a lack of resources for the key pillars of anti-trafficking - identification, protection, prosecution and prevention. For example, Amnesty International has called the UK government’s new anti-trafficking measures as 'not fit for purpose'.[124]

Victim identification and protection in the UK

In the UK, human trafficking cases are processed by the same officials to simultaneously determine the refugee and trafficking victim statuses of a person. However, criteria for qualifying as a refugee and a trafficking victim differ and they have different needs for staying in a country. A person may need assistance as a trafficking victim but his/her circumstances may not necessarily meet the threshold for asylum. In which case, not being granted refugee status affects their status as a trafficked victim and thus their ability to receive help. Reviews of the statistics from the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), a tool created by the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CoE Convention) to help states effectively identify and care for trafficking victims, found that positive decisions for non-European Union citizens were much lower than that of EU and UK citizens. According to data on the NRM decisions from April 2009 to April 2011, an average of 82.8% of UK and EU citizens were conclusively accepted as victims while an average of only 45.9% of non-EU citizens were granted the same status.[125] High refusal rates of non-EU people point to possible stereotypes and biases about regions and countries of origin which may hinder anti-trafficking efforts, since the asylum system is linked to the trafficking victim protection system.

Laura Agustin has suggested that in some cases 'anti-traffickers' ascribe victim status to immigrants who have made conscious and rational decisions to cross the borders knowing they will be selling sex and who do not consider themselves to be victims.[126] There have been instances in which the alleged victims of trafficking have actually refused to be rescued[127] or run away from the anti-trafficking shelters.[128]

In a 2013,[129] the Court of Appeal gave guidance to prosecuting authorities on the prosecution of victims of human trafficking, and held that the convictions of 3 Vietnamese children and one Ugandan woman ought to be quashed as the proceedings amounted to an abuse of the court's process.[130] The case was reported by the BBC[131] and one of the victims was interviewed by Channel 4.[132]

Law enforcement and the use of raids

In the U.S., services and protections for trafficked victims are related to cooperation with law enforcement. Legal procedures that involve prosecution and specifically, raids, are thus the most common anti-trafficking measures. Raids are conducted by law enforcement and by private actors and many organizations (sometimes in cooperation with law enforcement). Law enforcement perceive some benefits from raids, including the ability to locate and identify witnesses for legal processes, to dismantle "criminal networks," and to rescue victims from abuse.[106]

Critics, however, argue that anti-trafficking raids in the U.S. are misguided and do more harm than good to the victims, as well as being ineffective in holding traffickers accountable. Private actors who conduct raids are criticized because of their lack of experience and expertise in identifying actual victims and their lack of capacity to provide legal and social services for people rescued from raids.

The problems against anti-trafficking raids are related to the problem of the trafficking concept itself, as raids' purpose of fighting sex trafficking may be conflated with fighting prostitution. The Trafficking Victims Protection Re-authorization Act of 2005 (TVPRA) gives state and local law enforcement funding to prosecute customers of commercial sex, therefore some law enforcement agencies make no distinction between prostitution and sex trafficking. One study interviewed women who have experienced law enforcement operations as sex workers and found that during these raids meant to combat human trafficking, none of the women were ever identified as trafficking victims, and only one woman was asked whether she was coerced into sex work. The conflation of trafficking with prostitution, then, does not serve to adequately identify trafficking and help the victims. Raids are also problematic in that the women involved were most likely unclear about who was conducting the raid, what the purpose of the raid was, and what the outcomes of the raid would be.[106]

Law enforcement personnel agree that raids can intimidate trafficked persons and render subsequent law enforcement actions unsuccessful. Social workers and attorneys involved in anti-sex trafficking have negative opinions about raids. Service providers report a lack of uniform procedure for identifying trafficking victims after raids. The 26 interviewed service providers stated that local police never referred trafficked persons to them after raids. Law enforcement also often use interrogation methods that intimidate rather than assist potential trafficking victims. Additionally, sex workers sometimes face violence from the police during raids and arrests and in rehabilitation centers.[106]

As raids occur to brothels that may house sex workers as well as sex trafficked victims, raids affect sex workers in general. As clients avoid brothel areas that are raided but do not stop paying for sex, voluntary sex workers will have to interact with customers underground. Underground interactions means that sex workers take greater risks, where as otherwise they would be cooperating with other sex workers and with sex worker organizations to report violence and protect each other. One example of this is with HIV prevention. Sex workers collectives monitor condom use, promote HIV testing, and cares for and monitor the health of HIV positive sex workers. Raids disrupt communal HIV care and prevention efforts, and if HIV positive sex workers are rescued and removed from their community, their treatments are disrupted, furthering the spread of AIDS.[77]

Critics suggest reforms in law enforcement procedures so that raids are last resort, not violent, and are transparent in its purposes and processes. Furthermore, critics suggest that since any trafficking victims will probably be in contact with other sex workers first, working with sex workers may be an alternative to the raid and rescue model.[77]

End Demand programs

Critics argue that End Demand programs are ineffective in that prostitution is not reduced, "John's Schools" have little effect on deterrence and portray prostitutes negatively, and conflicts in interest arise between law enforcement and NGO service providers. A study found that Sweden's legal experiment (criminalizing clients of prostitution and providing services to prostitutes who want to exit the industry in order to combat trafficking) did not reduce the number of prostitutes, but instead increased exploitation of sex workers due to the higher risk nature of their work. The same study reported that johns' inclination to buy sex did not change as a result of John's Schools, and the programs targeted johns who are poor and colored immigrants. Some John's Schools also intimidate johns into not purchasing sex again by depicting prostitutes as drug addicts, HIV positive, violent, and dangerous, which further marginalizes sex workers. John's Schools require program fees, and police's involvement in NGOs who provide these programs create conflicts of interest especially with money involved.[83][133]

Alternative perspectives

Third-Way Feminism

The third-way feminist perspective of sex trafficking seeks to harmonize the dominant and liberal feminist views of sex trafficking. The dominant feminist view focuses on "sexualized domination," which includes issues of pornography, female sex labor in a patriarchal world, rape, and sexual harassment. Dominant feminism emphasizes sex trafficking as forced prostitution and considers the act exploitative. Liberal feminism sees all agents as capable of reason and choice. Liberal feminists support sex workers rights, and argue that women who voluntarily chose sex work are autonomous. The liberal feminist perspective finds sex trafficking problematic in that it overrides consent of individuals.[134]

Third-way feminism harmonizes the thoughts that while individuals have rights, overarching inequalities hinder women's capabilities. Third-way feminism also considers that women who are trafficked and face oppression do not all face the same kinds of oppression. For example, third-way feminist proponent Shelley Cavalieri identifies oppression and privilege in the intersections of race, class, and gender. Women from low socioeconomic class, generally from the Global South, face inequalities that differ from those of other sex trafficking victims. Therefore, it advocates for catering to individual trafficking victim because sex trafficking is not monolithic, and therefore there is not a one-size-fits-all intervention. This also means allowing individual victims to tell their unique experiences rather than essentializing all trafficking experiences. Lastly, third-way feminism promotes increasing women's agency both generally and individually, so that they have the opportunity to act on their own behalf.[134]

Third-way feminist perspective of sex trafficking is loosely related to Amartya Sen's and Martha Nussbaum's visions of the human capabilities approach to development. It advocates for creating viable alternatives for sex trafficking victims. Nussbaum articulated four concepts to increase trafficking victims' capabilities: education for victims and their children, microcredit and increased employment options, labor unions for low-income women in general, and social groups that connect women to one another.[134]

See also

- Bride-buying

- Called to Rescue

- Child camel jockey

- Child labour

- Child laundering

- Comfort woman

- Commercial sexual exploitation of children

- Human trafficking by country

- Debt bondage

- Exploitation

- Forced labour

- Forced prostitution

- Globalization

- Illegal immigration

- International Labor Organization

- List of organizations opposing human trafficking

- Kidnapping

- Military use of children

- People smuggling

- Serious and Organised Crime Group

- Sexual exploitation

- Sexual trafficking in Kosovo

- Sharecropping

- She Has a Name

- South East Asia Court of Women on HIV and Human Trafficking

- Trafficking of children

- Wife selling

- Migrant sex work

- Western princess

- Transnational efforts to prevent human trafficking

References

- ↑ WomanStats Maps, Woman Stats Project.

- ↑ "Trafficking in Persons Report 2011". U.S. Department of State. 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "UNODC on human trafficking and migrant smuggling". Unodc.org. 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Amnesty International - People smuggling". Amnesty.org.au. 2009-03-23. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ "Trafficking in organs, tissues and cells and trafficking in human beings for the purpose of the removal of organs" (PDF). United Nations. 2009. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ "Human trafficking for organs/tissue removal". Fightslaverynow.org. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ "Human trafficking for ova removal or surrogacy". Councilforresponsiblegenetics.org. 2004-03-31. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ Haken, Jeremy. "Transnational Crime In The Developing World". Global Financial Integrity. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ↑ DIRECTIVE 2011/36/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JH http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:101:0001:0011:EN:PDF

- ↑ "Convention on Transnational Organized Crime". Unodc.org. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ "United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime And The Protocols Thereto" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "UNODC - Signatories to the CTOC Trafficking Protocol". Treaties.un.org. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ "Economic Roots of Trafficking in the UNECE Region - Regional Prep. Meeting for Beijing". Unece.org. 15 December 2004. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ "Forced Labor and Human Trafficking: Estimating the Profits". Cornell University ILR School. 2005-03-01. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "UN-backed container exhibit spotlights plight of sex trafficking victims". Un.org. 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ↑ "Difference between Smuggling and Trafficking". Anti-trafficking.net. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Labor trafficking fact sheet, National Human Trafficking Resource Center.

- ↑ "A global alliance against forced labour", ILO, 11 May 2005.

- ↑ McCarthy, Ryan. "13 Products Most Likely to Be Made By Child or Forced Labor". Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Counter-Trafficking and Assistance to Vulnerable Migrants, Annual Report of activities 2011 Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Preventing Human Trafficking". Unodc.org. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Un.Gift.Hub". Ungift.org. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "UN.GIFT_Kern_gesamt.pdf" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "What is human-trafficking". Unodc.org. 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "Blue Heart Campaign Against Human Trafficking - Mexico Campaign". Unodc.org. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "Kanaal van UNODCHQ". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ Blue Heart Campaign Against Human Trafficking

- ↑ "Demi Moore and Ashton Kutcher join Secretary-General to launch Trust Fund for victims of human trafficking". Unodc.org. 2010-11-04. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "Global report on trafficking in persons". Unodc.org. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ "Global report on trafficking in persons". Unodc.org. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ "Combating Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery". Polaris Project. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ "National Human Trafficking Resource Center | Polaris Project | Combating Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery". Polaris Project. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ "State Map | Polaris Project | Combating Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery". Polaris Project. 2007-12-07. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ Presidential Proclamation - National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month, The White House.

- ↑ "Council of Europe - Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS No. 197)". Conventions.coe.int. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "Council of Europe - Action against Trafficking in Human Beings: Publications". Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ "Council of Europe - European Court of Human Rights". Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ "Council of Europe - European Court of Human Rights". Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ "Combating Trafficking in Human Beings - Secretariat - Office of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings". Osce.org. 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ Cho, Seo-Young, Axel Dreher, and Eric Neumayer. "The Spread of Anti-trafficking Policies-Evidence from a New Index." Available at SSRN 1776842 (2011).

- ↑ "Human-trafficking-research.org". Human-trafficking-research.org. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ Williams, Rachel (2008-07-03). "British-born teenagers being trafficked for sexual exploitation within UK, police say". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Mother sold girl for sex, May 7, 2010, The Age.

- ↑ Agents in the UEFA spotlight at the Wayback Machine (archived April 30, 2009), UEFA, 29 September 2006. (archived from the original on 2009-04-30)

- ↑ "LatAm - Brazil - Child Prostitution Crisis". Libertadlatina.org. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ "The Age: China sets up website to recover trafficked children: report". Melbourne: News.theage.com.au. 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ "The Two Faces of Inter-country Adoption: The Significance of the Indian Adoption Scandals" at the Wayback Machine (archived March 26, 2009) by David M. Smolin, Seton Hall Law Review, 35:403–493, 2005. (archived from the original on 2009-03-26)

- ↑ "Child Laundering: How the Inter-country Adoption System Legitimizes and Incentivizes the Practices of Buying, Trafficking, Kidnapping, and Stealing Children" by David M. Smolin, bepress Legal Series, Working Paper 749, August 29, 2005.