Human body

| Human body | |

|---|---|

| |

| Human body features, showing bodies whose body hair and male facial hair has been removed | |

The human body is the entire structure of a human being and comprises a head, neck, trunk (which includes the thorax and abdomen), two arms and hands and two legs and feet. Every part of the body is composed of various types of cell.[1] At maturity, the estimated number of cells in the body is given as 37.2 trillion. This number is stated to be of partial data and to be used as a starting point for further calculations. The number given is arrived at by totalling the cell numbers of all the organs of the body and cell types.[2] The composition of the human body shows it to be composed of a number of certain elements in different proportions.

The study of the human body involves anatomy and physiology. The human body can show anatomical non-pathological anomalies which need to be able to be recognised. Physiology focuses on the systems and their organs of the human body and their functions. Many systems and mechanisms interact in order to maintain homeostasis.

Structure

Skeletal structure frames the overall shape of the body and does not alter much over a lifetime. General body shape (and female body shape) is influenced by the distribution of muscle and fat tissue and also affected by various hormones. The average height of an adult male human (in developed countries) is about 1.7–1.8 m (5'7" to 5'11") and the adult female is about 1.6–1.7 m (5'2" to 5'7") .[3] Height is largely determined by genes and diet. Body type and composition are influenced by factors such as genetics, diet, and exercise.

Composition

The composition of the human body can be referred to in terms of its water content, elements content, tissue types or material types. The adult human body contains approximately 60% water, and so makes up a significant proportion of the body, both in terms of weight and volume. Water content can vary from a high 75% in a newborn infant to a lower 45% in an obese person. (These figures are necessarily statistical averages).

Composition by tissue type can refer to the cells of the human body where the vast majority of cells are not human but bacterial cells and also archaea cells, particularly methanogens such as Methanobrevibacter smithii. The whole population of microbiota include microorganisms of the skin and other body parts and these in total are also termed the human microbiome the largest proportion of these form the the gut flora.

The proportions of the elements of the body can be referred to in terms of the main elements, minor ones and trace elements. Material type may also be referred to as including water, protein, connective tissue, fats, carbohydrates and bone.

Human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body.[4] Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy (histology)[4] Gross anatomy (also called topographical anatomy, regional anatomy, or anthropotomy) is the study of anatomical structures that can be seen by the naked eye.[4] Microscopic anatomy involves the use of microscopes to study minute anatomical structures, and is the field of histology which studies the organization of tissues at all levels, from cell biology (previously called cytology), to organs.[4] Anatomy, human physiology (the study of function), and biochemistry (the study of the chemistry of living structures) are complementary basic medical sciences that are generally taught together (or in tandem) to students studying medical sciences.

In some of its facets human anatomy is closely related to embryology, comparative anatomy and comparative embryology,[4] through common roots in evolution; for example, much of the human body maintains the ancient segmental pattern that is present in all vertebrates with basic units being repeated, which is particularly obvious in the vertebral column and in the ribcage, and which can be traced from the somitogenesis stage in very early embryos.

Generally, physicians, dentists, physiotherapists, nurses, paramedics, radiographers, and students of certain biological sciences, learn gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy from anatomical models, skeletons, textbooks, diagrams, photographs, lectures, and tutorials. The study of microscopic anatomy (or histology) can be aided by practical experience examining histological preparations (or slides) under a microscope; and in addition, medical and dental students generally also learn anatomy with practical experience of dissection and inspection of cadavers (corpses). A thorough working knowledge of anatomy is required for all medical doctors, especially surgeons, and doctors working in some diagnostic specialities, such as histopathology and radiology.

Human anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry are basic medical sciences, which are generally taught to medical students in their first year at medical school. Human anatomy can be taught regionally or systemically;[4] that is, respectively, studying anatomy by bodily regions such as the head and chest, or studying by specific systems, such as the nervous or respiratory systems. The major anatomy textbook, Gray's Anatomy, has recently been reorganized from a systems format to a regional format, in line with modern teaching.[5][6]

Anatomical variations

In human anatomy, the term anatomical variation refers to a non-pathologic anatomic structure that is different from what is observed in most people. The possible anatomic variations in each organ and its arterial and venous supply must be known by physicians, such as surgeons or radiologists, in order to correctly identify those structures. Unlike congenital anomalies, anatomic variations are typically inconsequential and do not constitute a disorder. The accessory soleus muscle is one such variation.[7]

Human physiology

Human physiology is the science of the mechanical, physical, bioelectrical, and biochemical functions of humans in good health, their organs, and the cells of which they are composed. Physiology focuses principally at the level of organs and systems. Most aspects of human physiology are closely homologous to corresponding aspects of animal physiology, and animal experimentation has provided much of the foundation of physiological knowledge. Anatomy and physiology are closely related fields of study: anatomy, the study of form, and physiology, the study of function, are intrinsically related and are studied in tandem as part of a medical curriculum.

The study of how physiology is altered in disease is pathophysiology.

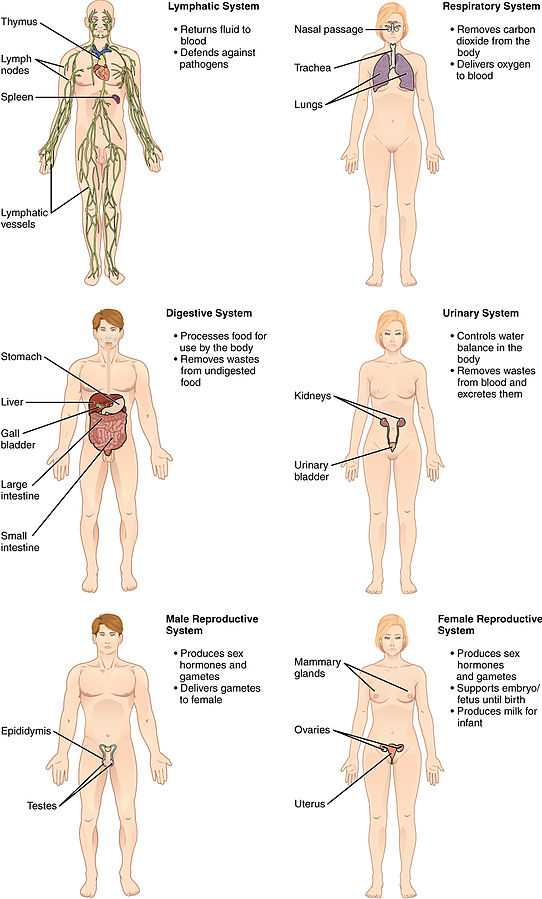

Systems

The human body consists of many interacting systems. Each system contributes to the maintenance of homeostasis, of itself, other systems, and the entire body. A system consists of organs, which are functional collections of tissue. Systems do not work in isolation, and the well-being of the person depends upon the well-being of all the interacting body systems.

| System | Clinical study | Physiology | |

| | The nervous system consists of the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system. The brain is the organ of thought, emotion, memory, and sensory processing, and serves many aspects of communication and controls various systems and functions. The special senses consist of vision, hearing, taste, and smell. The eyes, ears, tongue, and nose gather information about the body's environment. | neuroscience, neurology (disease), psychiatry (behavioral), ophthalmology (vision), otolaryngology (hearing, taste, smell) | neurophysiology |

| The musculoskeletal system consists of the human skeleton (which includes bones, ligaments, tendons, and cartilage) and attached muscles. It gives the body basic structure and the ability for movement. In addition to their structural role, the larger bones in the body contain bone marrow, the site of production of blood cells. Also, all bones are major storage sites for calcium and phosphate. This system can be split up into the muscular system and the skeletal system. | orthopedics (bone and muscle disorders and injuries) | cell physiology, musculoskeletal physiology, osteology (skeleton), arthrology (articular system), myology (muscular system)[8] |

.svg.png) | The circulatory system or cardiovascular system comprises the heart and blood vessels (arteries, veins, and capillaries). The heart propels the circulation of the blood, which serves as a "transportation system" to transfer oxygen, fuel, nutrients, waste products, immune cells, and signalling molecules (i.e., hormones) from one part of the body to another. The blood consists of fluid that carries cells in the circulation, including some that move from tissue to blood vessels and back, as well as the spleen and bone marrow. | cardiology (heart), hematology (blood) | cardiovascular physiology[9][10] The heart itself is divided into three layers called the endocardium, myocardium and epicardium,(liquidation) which vary in thickness and function.[11] |

| | The respiratory system consists of the nose, nasopharynx, trachea, and lungs. It brings oxygen from the air and excretes carbon dioxide and water back into the air. | pulmonology | respiratory physiology |

| The gastrointestinal system consists of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, gut (small and large intestines), and rectum, as well as the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, and salivary glands. It converts food into small, nutritional, non-toxic molecules for distribution by the circulation to all tissues of the body, and excretes the unused residue. Sometimes also called the digestive system.[citation needed] | gastroenterology | gastrointestinal physiology |

| The integumentary system consists of the covering of the body (the skin), including hair and nails as well as other functionally important structures such as the sweat glands and sebaceous glands. The skin provides containment, structure, and protection for other organs, but it also serves as a major sensory interface with the outside world. | dermatology | cell physiology, skin physiology |

| The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. It removes water from the blood to produce urine, which carries a variety of waste molecules and excess ions and water out of the body. | nephrology (function), urology (structural disease) | renal physiology |

| | The reproductive system consists of the gonads and the internal and external sex organs. The reproductive system produces gametes in each sex, a mechanism for their combination, and a nurturing environment for the first 9 months of development of the infant. | gynecology (women), andrology (men), sexology (behavioral aspects) embryology (developmental aspects), obstetrics (partition) | reproductive physiology |

| The immune system consists of the white blood cells, the thymus, lymph nodes and lymph channels, which are also part of the lymphatic system. The immune system provides a mechanism for the body to distinguish its own cells and tissues from alien cells and substances and to neutralize or destroy the latter by using specialized proteins such as antibodies, cytokines, and toll-like receptors, among many others. | immunology | immunology |

| The main function of the lymphatic system is to extract, transport and metabolize lymph, the fluid found in between cells. The lymphatic system is very similar to the circulatory system in terms of both its structure and its most basic function (to carry a body fluid). | oncology, immunology | oncology, immunology |

| The endocrine system consists of the principal endocrine glands: the pituitary, thyroid, adrenals, pancreas, parathyroids, and gonads, but nearly all organs and tissues produce specific endocrine hormones as well. The endocrine hormones serve as signals from one body system to another regarding an enormous array of conditions, and resulting in variety of changes of function. There is also the exocrine system. | endocrinology | endocrinology |

Homeostasis

The term homeostasis refers to a system that regulates its internal environment and maintains a stable, relatively constant condition; such as maintaining an equal temperature or pH. This is required for the body to function sufficiently. Without a relatively constant pH, temperature, blood flow, and position, it would be impossible for the human to survive.

Many interacting systems and mechanisms act to maintain the human's internal environment. The nervous system receives information from the body and transmits this to the brain via neurotransmitters. The endocrine system may release hormones to help regular blood pressure and volume. Cell metabolism may help to maintain the blood's pH.

Society and culture

Depiction

Anatomy has become a key part of the visual arts. Basic concepts of how muscles and bones function and change with movement are vital in drawing, painting or animating a human figure. Many books (such as "Human Anatomy for Artists: The Elements of Form") have been written as guides to drawing the human body anatomically correctly.[12] Leonardo da Vinci sought to improve his art through a better understanding of human anatomy. In the process he advanced both human anatomy and its representation in art.

Because the structure of living organisms is complex, anatomy is organized by levels, from the smallest components of cells to the largest organs and their relationship to others.

Appearance

History of anatomy

The history of anatomy has been characterized, over a long period of time, by an ongoing, developing understanding of the functions of organs and structures in the human body. Methods have advanced dramatically, from the simple examination by dissection of animals and cadavers (corpses), to the development and use of the microscope, to the far more technological advances of the electron microscope and other complex techniques developed since the beginning of the 20th century. During the 19th and early 20th centuries it was the most prominent biological field of scientific study. [13]

History of physiology

The study of human physiology dates back to at least 420 B.C. and the time of Hippocrates, the father of western medicine.[14] The critical thinking of Aristotle and his emphasis on the relationship between structure and function marked the beginning of physiology in Ancient Greece, while Claudius Galenus (c. 126-199 A.D.), known as Galen, was the first to use experiments to probe the function of the body. Galen was the founder of experimental physiology.[15] The medical world moved on from Galenism only with the appearance of Andreas Vesalius and William Harvey.[16]

During the Middle Ages, the ancient Greek and Indian medical traditions were further developed in Islamic medicine. Notable work in this period was done by Avicenna (980-1037), author of the The Canon of Medicine, and Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), among others.[citation needed]

Following from the Middle Ages, the Renaissance brought an increase of physiological research in the Western world that triggered the modern study of anatomy and physiology. Andreas Vesalius was an author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica.[17] Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy.[18] Anatomist William Harvey described the circulatory system in the 17th century,[19] demonstrating the fruitful combination of close observations and careful experiments to learn about the functions of the body, which was fundamental to the development of experimental physiology. Herman Boerhaave is sometimes referred to as a father of physiology due to his exemplary teaching in Leiden and textbook Institutiones medicae (1708).[citation needed]

In the 18th century, important works in this field were by Pierre Cabanis, a French doctor and physiologist.[citation needed]

In the 19th century, physiological knowledge began to accumulate at a rapid rate, in particular with the 1838 appearance of the Cell theory of Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann. It radically stated that organisms are made up of units called cells. Claude Bernard's (1813–1878) further discoveries ultimately led to his concept of milieu interieur (internal environment), which would later be taken up and championed as "homeostasis" by American physiologist Walter Cannon (1871–1945).

In the 20th century, biologists also became interested in how organisms other than human beings function, eventually spawning the fields of comparative physiology and ecophysiology.[20] Major figures in these fields include Knut Schmidt-Nielsen and George Bartholomew. Most recently, evolutionary physiology has become a distinct subdiscipline.[21]

The biological basis of the study of physiology, integration refers to the overlap of many functions of the systems of the human body, as well as its accompanied form. It is achieved through communication that occurs in a variety of ways, both electrical and chemical.

In terms of the human body, the endocrine and nervous systems play major roles in the reception and transmission of signals that integrate function. Homeostasis is a major aspect with regard to the interactions in the body.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human body. |

Further reading

- Raincoast Books (2004). Encyclopedic Atlas Human Body. Raincoast Books. ISBN 978-1-55192-747-3.

- Daniel D. Chiras (1 June 2012). Human Body Systems: Structure, Function, and Environment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4496-4793-3.

- Adolf Faller; Michael Schünke; Gabriele Schünke; Ethan Taub, M.D. (2004). The Human Body: An Introduction to Structure and Function. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-58890-122-4.

- Richard Walker (30 March 2009). Human Body. Dk Pub. ISBN 978-0-7566-4545-8.

- DK Publishing (18 June 2012). Human Body: A Visual Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-4654-0143-4.

- DK Publishing (30 August 2010). The Complete Human Body: The Definitive Visual Guide. ISBN 978-0-7566-7509-7.

- Saddleback (1 January 2008). Human Body. Saddleback Educational Publ. ISBN 978-1-59905-234-2.

- Babsky, Evgeni; Boris Khodorov, Grigory Kositsky, Anatoly Zubkov (1989). Evgeni Babsky, ed. Human Physiology, in 2 vols. Translated by Ludmila Aksenova; translation edited by H. C. Creighton (M.A., Oxon). Moscow: Mir Publishers. ISBN 5-03-000776-8.

- Sherwood, Lauralee (2010). Human Physiology from cells to systems (Hardcover) (7 ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/cole. ISBN 978-0-495-39184-5.

References

- ↑ Cell Movements and the Shaping of the Vertebrate Body in Chapter 21 of Molecular Biology of the Cell fourth edition, edited by Bruce Alberts (2002) published by Garland Science.

The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing embryos. It is also common to describe small molecules such as amino acids as "molecular building blocks". - ↑ Bianconi, E. Piovesin, A. et al. Annals of Human Biology 2013 Nov-Dec;40(6) 463-71 PMID 23829164

- ↑ http://www.human-body.org/ (dead link)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Introduction page, "Anatomy of the Human Body". Henry Gray. 20th edition. 1918". Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ↑ "Publisher's page for Gray's Anatomy. 39th edition (UK). 2004. ISBN 0-443-07168-3". Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ↑ "Publisher's page for Gray's Anatomy. 39th edition (US). 2004. ISBN 0-443-07168-3". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ↑ Anatomy of and Abnormalities Associated with Kager's Fat Pad, American Journal of Roentgenology

- ↑ Moore, Keith L., Dalley, Arthur F., Agur Anne M. R. (2010). Moore's Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Phildadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-60547-652-0.

- ↑ "Cardiovascular System". U.S. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Human Biology and Health. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. 1993. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ "The Cardiovascular System". SUNY Downstate Medical Center. 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Goldfinger, Eliot (1991). Human Anatomy for Artists: The Elements of Form. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505206-4.

- ↑ Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman. Tarikh llm Tashrih [An extensive Book in Urdu on History of anatomy] (1967), Tibbi Academy, Delhi, Second revised edition 2009 (ISBN 978-81-906070-), Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences, Aligarh

- ↑ "Physiology - History of physiology, Branches of physiology". www.Scienceclarified.com. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Fell, C.; Griffith Pearson, F. (November 2007). "Thoracic Surgery Clinics: Historical Perspectives of Thoracic Anatomy". Thorac Surg Clin 17 (4): 443–8, v. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.001.

- ↑ "Galen". Discoveriesinmedicine.com. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ "Page through a virtual copy of Vesalius's De Humanis Corporis Fabrica". Archive.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ "Andreas Vesalius (1514-1567)". Ingentaconnect.com. 1999-05-01. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (2004). "Soul Made Flesh: The Discovery of the Brain - and How It Changed the World". J Clin Invest 114 (5): 604–604. doi:10.1172/JCI22882.

- ↑ Feder, Martin E. (1987). New directions in ecological physiology. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34938-3.

- ↑ Garland, Jr, Theodore; Carter, P. A. (1994). "Evolutionary physiology". Annual Review of Physiology 56 (56): 579–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.003051. PMID 8010752.

External links

| Look up body in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Human Physiology |

- Human Physiology textbook at Wikibooks

- (English) (Arabic) The Book of Humans from the early 18th century

- Referencing site and detailed pictures showing information on the human body anatomy and structure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||