Hui people

Hui Muslims | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10,586,087[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

|

Mandarin, Dungan, other Chinese dialects | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Dungan, Panthay, Dongxiang, Han Chinese, other Sino-Tibetan peoples |

| Hui people | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 回族 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

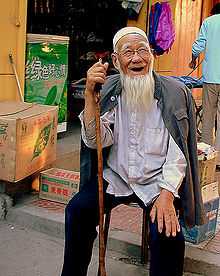

The Hui people (Chinese: 回族; pinyin: Huízú, Xiao'erjing: ﺧُﻮِ ذُﻮْ / حواري, Dungan: Хуэйзў/Huejzw) are a predominantly Muslim ethnic group in China. Hui people are found throughout the country, though they are concentrated mainly in the Northwestern provinces and the Central Plain. According to a 2011 census, China is home to approximately 10.5 million Hui people, the majority of whom are Chinese-speaking practitioners of Islam, though some practice other religions. Although many Hui people are ethnically similar to Han Chinese, the group has retained some Arabic, Persian and Central Asian features, their ethnicity and culture having been shaped profoundly by their position along the Silk Road trading route.

In the People's Republic of China, the Hui people are one of 56 officially recognized ethnic groups. Under this definition, the Hui people are defined to include all historically Muslim communities not included in China's other ethnic groups.[2] Since speakers of various Turkic and Mongolic languages are classified under these other groups (e.g., Uyghurs, Dongxiang), the officially recognized Hui ethnic group consists predominantly of Chinese language speakers.[3] In fact, the Hui nationality is unique among China's officially recognized ethnic minorities in that it does not have any particular non-Sinitic language associated with it.[4]

Most Hui are similar in culture to Han Chinese[5] with the exception that they practice Islam, and have some distinctive cultural characteristics as a result. For example, as Muslims, they follow Islamic dietary laws and reject the consumption of pork, the most common meat consumed in Chinese culture,[6] and have also given rise to their variation of Chinese cuisine, Chinese Islamic cuisine: as well as Muslim Chinese martial arts. Their mode of dress also differs primarily in that men wear white caps and women wear headscarves or (occasionally) veils, as is the case in most Islamic cultures.

Etymology and identification

The name "Hui" is officially given by the People's Republic of China government, who define a Hui as a Chinese speaker with foreign Muslim ancestry.[citation needed] Practicing the Islamic religion is not required. Use of the Hui category to describe foreign Muslims moving into China dates back to the Song dynasty (960–1279).

Pan-Turkic Uyghur activist Masud Sabri viewed the Hui people as Muslim Han Chinese and separate from his own people, noting that with the exception of religion, their customs and language were identical with the Han.[7]

The Hui people are of varied ancestry,[8] and many are direct descendants of Silk Road travelers. Their ancestors include Central Asian, Arabs, and Persian who married Han Chinese. West Eurasian DNA is prevalent among the Hui people, 6.7% Hui people's maternal genetics have an West Eurasian origin.[9] Several medieval dynasties, particularly the Tang Dynasty, Song Dynasty, and Mongol Yuan Dynasty encouraged immigration from predominantly Muslim Persia and Central Asia, with both dynasties welcoming traders from these regions and appointing Central Asian officials. In the subsequent centuries, they gradually mixed with Mongols and Han Chinese, and the Hui people were formed.

Nonetheless, included among the Hui in Chinese census statistics (and not officially recognized as separate ethnic groups) are members of a few small non-Chinese speaking communities. Among them are several thousand Utsuls in southern Hainan province, who speak an Austronesian language (Tsat) related to that of the Cham Muslim minority of Vietnam, and who are said to be descended from Chams who migrated to Hainan.[10] A small Muslim minority among Yunnan's Bai people are classified as Hui as well (even if they are Bai speakers),[11] as are some groups of Tibetan Muslims.[10] The Hui people are more concentrated in Northwestern China (Ningxia, Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang), but communities exist across the country, e.g. Beijing, Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Hainan, Yunnan.

Origins

Faced with the devastating An Lushan Rebellion, Emperor Suzong of Tang wrote a desperate letter to Al-Mansur requesting armed assistance. Al-Mansur responded by sending 7000 cavalry to China in order to aid Emperor Suzong of Tang. It is believed that those Muslim warriors were the originators of the Hui people.[12]

"Huihui" and "Hui"

The words Huihui (回回), which was the usual generic term for China's Muslims during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, is thought to have its origin in the earlier Huihe (回纥) or Huihu (回鶻), which was the name for the Uyghur State of the 8th and 9th century.[13] Although the ancient Uyghurs were neither Muslims nor were very directly related to today's Uyghur people,[13] the name Huihui came to refer to foreigners, regardless of language or origin, by the time of the Yuan (1271–1368)[14] and Ming Dynasties (1368–1644),[13] since during the Yuan Dynasty massive amounts of Muslims came from the west, since the Uyghur land was in the west, this led the Chinese to call all foreigners of all religions, Muslims, Nestorian Christians, and Jews as "HuiHui".

Genghis Khan called both foreign Jews and Muslims in China "Hui Hui" when he forced them to stop Halal and Kosher methods of preparing food:[15]

Among all the [subject] alien peoples only the Hui-hui say “we do not eat Mongol food”. [Cinggis Qa’an replied:] “By the aid of heaven we have pacified you; you are our slaves. Yet you do not eat our food or drink. How can this be right?” He thereupon made them eat. “If you slaughter sheep, you will be considered guilty of a crime.” He issued a regulation to that effect ... [In 1279/1280 under Qubilai] all the Muslims say: “if someone else slaughters [the animal] we do not eat”. Because the poor people are upset by this, from now on, Musuluman [Muslim] Huihui and Zhuhu [Jewish] Huihui, no matter who kills [the animal] will eat [it] and must cease slaughtering sheep themselves, and cease the rite of circumcision.

The Chinese called Muslims, Jews, and Christians in ancient times by the same name, "Hui Hui". Christians were called "Hui who abstain from animals without the cloven foot", Muslims were called "Hui who abstain from pork", Jews were called "Hui who extract the sinews". Hui zi or Hui Hui is presently used almost exclusively for Muslims, but Jews were still called Lan mao Hui zi which means "Blue cap Hui zi". Jews and Muslims in China shared the same name for synagogue and mosque, which were both called Qingzhen si "Temple of Purity and Truth", the name dated to the thirteenth century. The synagogue and mosques were also known as Libai Si (temple of worship). The Kaifeng Jews were nicknamed "Teaou kin jiao" (挑筋教, extract sinew religion). A tablet indicated that Judaism was once known as "Yih-tsze-lo-nee-keaou" (一赐乐业教, Israelitish religion) and synagogues known as Yih-tsze lo née leen (Israelitish Temple), but it faded out of use.[16]

Islam was originally called Dashi Jiao during the Tang Dynasty, when Muslims first appeared in China. "Dashi Fa" literally means "Arab law", in old Chinese (modern calls Alabo).[17] Since almost all Muslims in China were exclusively foreign Arabs or Persians at the time, it was barely mentioned by the Chinese, unlike other religions like Zoroastrism, Mazdaism, and Nestorian Christianity which gained followings in China.[18] As an influx of foreigners, such as Arabs, Persians, Jews, and Christians, most of them, but not all of them were Muslims who came from western regions, they were labelled as Semu people, but were also mistaken by Chinese as Uyghur, due to them coming from the west (uyghur lands).[19] so the name "Hui Hui" was applied to them, and eventually became the name to refer to Muslims.

Another, probably unrelated, early use of the word Huihui comes from the History of Liao Dyansty, which mentions Yelü Dashi, the 12th-century founder of the Kara-Khitan Khanate, defeating the Huihui Dashibu (回回大食部) people near Samarkand – apparently, referring to his defeat of the Khwarazm ruler Ahmed Sanjar in 1141.[20] Khwarazm is referred to as Huihuiguo in the Secret History of the Mongols as well.[21] The widespread and rather generic application of the name "Huihui" in Ming China was attested by foreign visitors as well. Matteo Ricci, the first Jesuit to reach Beijing (1598), noted that "Saracens are everywhere in evidence . . . their thousands of families are scattered about in nearly every province"[22] Ricci noted that the term Huihui or Hui was applied by Chinese not only to "Saracens" (Muslims) but also to Chinese Jews and supposedly even to Christians.[23] In fact, when the reclusive Wanli Emperor first saw a picture of Ricci and Diego de Pantoja, he supposedly exclaimed, "Hoei, hoei. It is quite evident that they are Saracens", and had to be told by an eunuch that they actually weren't, "because they ate pork".[24] The 1916 Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8 said that Chinese Muslims always called themselves Huihui or Huizi, and that neither themselves nor other people called themselves Han, and they disliked people calling them Dungan.[25] A French army Commandant Viscount D'Ollone wrote a report on what he saw among Hui in 1910, during the Qing Dynasty, he reported that due to religion, Hui were classed as a different nationality from Han as if they were one of the other minority groups like Miao.[26]

While Huihui or Hui remained a generic name for all Muslims in Imperial China, specific terms were sometimes used to refer to particular groups, e.g. Chantou Hui ("turbaned Hui") for Uyghurs, Dongxiang Hui and Sala Hui for Dongxiang and Salar people, and sometimes even Han Hui (漢回) ("Chinese Hui") for the (presumably Chinese-speaking) Muslims more assimilated into the Chinese mainstream society.[27][28] Some scholars also say that some Hui used to call themselves 回漢子 (Hui Hanzi) "Muslim Han" but now the Communist regime has separated them from other Chinese and placed them into a separate minzu, "Huizu".[29]

Under the aegis of the Communist Party in the 1930s the term Hui was defined to indicate only Sinophone Muslims. In 1941, this was clarified by a Communist Party committee comprising ethnic policy researchers in a treatise entitled "On the question of Huihui Ethnicity" (Huihui minzu wenti). This treatise defined the characteristics of the Hui nationality as follows: the Hui or Huihui constitute an ethnic group associated with, but not defined by, the Islamic religion and they are descended primarily from Muslims who migrated to China during the Mongol-founded Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), as distinct from the Uyghur and other Turkic-speaking ethnic groups in Xinjiang. The Nationalist government had recognised all Muslims as one of "the five peoples"—alongside the Manchus, Mongols, Tibetans and Han Chinese—that constituted the Republic of China. The new Communist interpretation of Chinese Muslim ethnicity marked a clear departure from the ethno-religious policies of the Nationalists, and had emerged as a result of the pragmatic application of Stalinist ethnic theory to the conditions of the Chinese revolution.[30]

These days, within the PRC, Huizu and is the standard term for the "Hui nationality" (ethnic group), and Huimin, for "Hui people" or "a Hui person". The traditional expression Huihui, its use now largely restricted to rural areas, would sound quaint, if not outright demeaning, to modern urban Chinese Muslims.[31]

A traditional Chinese term for Islam is 回教 (pinyin: Huíjiào, literally "the religion of the Hui"). However, since the early days of the PRC, thanks to the arguments of such Marxist Hui scholars as Bai Shouyi, the standard term for "Islam" within the PRC has become the transliteration 伊斯蘭教 (pinyin: 'Yīsīlán jiào, literally "Islam religion").[32] The more traditional term Huijiao remains in use in Singapore, Taiwan, and other overseas Chinese communities.[33]

Qīngzhēn (清真, literally "pure and true") has also been a popular term for the things Muslim since the Yuan or Ming Dynasty. Dru Gladney suggests that a good translation for it would be Arabic tahára. i.e. "ritual or moral purity"[34] The usual term for a mosque is qīngzhēn sì (清真寺), i.e. "true and pure temple", and qīngzhēn is commonly used to refer to halal eating establishments and bathhouses.

"Dungan"

Hui people everywhere are referred to by Central Asian Turkic speakers and Tajiks as Dungans. This term has a long pedigree as well. The region's historian Joseph Fletcher cites Turkic and Persian manuscripts related to the preaching of the 17th century Kashgarian Sufi master Muhammad Yūsuf (or, possibly, his son Afaq Khoja) inside the Ming Empire (in today's Gansu and/or Qinghai), where the Kashgarian preacher is told to have converted 'ulamā-yi Tunganiyyāh (i.e., "Dungan ulema") into Sufism.[19]

In English and German, the ethnonym "Dungan", in various spelling forms, was attested as early as 1830s, typically referring to the Hui people of Xinjiang. For example, James Prinsep in 1835 mentions Muslim "Túngánis" in "Chinese Tartary".[35] The word (mostly in the form "Dungani" or "Tungani", sometimes "Dungens" or "Dungans") acquired some currency in English and other western languages when a number of books in the 1860-70s discussed the Dungan revolt in north-western China.

Later authors continued to use the term Dungan (in various transcriptions) for, specifically, the Hui people of Xinjiang. For example, Owen Lattimore, writing ca. 1940, maintains the terminological distinction between these two related groups: the "Tungkan" which is the older Wade-Giles spelling for "Dungan", described by him as the descendants of the Gansu Hui people resettled in Xinjiang in 17-18th centuries, vs. e.g. the "Gansu Moslems" or generic "Chinese Moslems".[36]

The name "Dungan" was used to refer to all Muslims coming from China proper, such as Dongxiang and Salar in addition to Hui. They were called Chinese Muslims by westerners. Reportedly, the Hui disliked the term Dungan and did not want people to refer to them as Dungans, calling themselves either HuiHui or Huizi.[37]

In the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and its successor countries, the term "Dungans" (дунгане) became the standard name for the descendants of Chinese-speaking Muslims who emigrated to the Russian Empire (mostly to today's Kyrgyzstan and south-eastern Kazakhstan) in the 1870s and 1880s.[38]

"Muslim Chinese"

Hui people are often referred to as "Muslim Chinese" or "Chinese Muslims" in Western media. However, this is a misnomer. Neither all Hui are Muslims, nor are all Chinese Muslims Hui. For example, Li Yong is a famous Han Chinese who believes in Islam, and Hui Liangyu is a famous atheist Hui. In addition, most Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kirghiz and Dongxiang in China are Muslims.

Other terms

In Thailand, Chinese Muslims are referred to as Chin Ho, in Burma and Yunnan Province, as Panthay.

During the Qing Dynasty, the term Zhongyuan ren (中原人, people from the Central Plain) was synonymous with being Chinese, especially referring to Han Chinese and Hui in Xinjiang or Central Asia. While Hui do not consider themselves Han and are not Han, the Hui consider themselves Chinese and refer to themselves as Zhongyuan ren.[39] The Dungan people, descendants of Hui who fled to Central Asia, called themselves Zhongyuan ren in addition to the standard labels Lao Huihui and Huizi.[40] Zhongyuan ren was used by Turkic Muslims to refer to ethnic Chinese. When Central Asian invaders from Kokand invaded Kashgar, in a letter the kokandi commander criticizes the Kashgari Turkic Muslim Ishaq for allegedly not behaving like a Muslim and wanting to be a Zhongyuan ren (Chinese).[41][42]

Pusuman was a name used by Chinese during the Yuan Dynasty. It could have been a corruption of Musalman (The Persian word for Muslim), or another name for Persians. It either means Muslim or Persian.[43][44] Pusuman Kuo (Pusuman Guo) referred to the country where they came from.[45][46] The name "Pusuman zi" (pusuman script), was used to refer to the script that the HuiHui (Muslims) were using.[47][48]

During the Tang Dynasty mostly Arabic speaking Muslims visited China, Persian speakers formed the majority of Muslims in China in the Song and Yuan dynasties.[49]

In English, the term "Mohammedan" was originally used to refer to Chinese of Islamic faith during the 19th century.[50] During the first half of the 20th century, writers such as Edgar Snow and Owen Lattimore who visited the Hui homeland also used the term "Mohammedans" in their accounts. The term gradually fell into disuse, and today the term "Hui" is used in English.

History

Origins

The Hui Chinese have diverse origins, and many of whom are direct descendants of Silk Road travelers. Some in the southeast coast (Guangdong, Fujian) and in major trade centers elsewhere in China are of mixed local and foreign descent. The foreign element, although greatly diluted, came from Arab (Dashi) and Persian (Bosi) traders, who brought Islam to China. These foreigners settled in China and gradually intermarried into the surrounding population while converting them to Islam, while they in turn assimilated in all aspects of Chinese culture, keeping only their distinctive religion.[51]

Early European explorers speculated that T'ung-kan (Hui, called "Chinese Mohammedan") in Xinjiang originated from Khorezmians who were transported to China by the Mongols, and that they were descended from a mixture of Chinese, Iranians, and Turkic peoples. They also reported that the T'ung-kan were Shafi'ites, which the Khorezmians were also.[52]

A totally different explanation is available for the Hui people of Yunnan and Northwestern China, whose ethnogenesis might be a result of the convergence of large number of Mongol, Turkic, Iranian or other Central Asian settlers in these regions, who were recruited by the Mongol-founded Yuan Dynasty either as officials (the semu, who formed the second-highest stratum in the Yuan Empire's ethnic hierarchy, after the Mongols themselves, but before both northern and southern Chinese) or artisans.[53][54] It was documented that a proportion of the ancestral nomad or military ethnic groups were originally Nestorian Christians many of whom later converted to Islam, while under the Sinicizing pressures of the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Southeastern Muslims also have a much longer tradition of synthesizing Confucian teachings with the Sharia and Qur'anic teachings, and were reported to have been contributing to the Confucian officialdom since the Tang period. Among the Northern Hui, on the other hand, there are strong influences of Central Asian Sufi schools such as Kubrawiyya, Qadiriyya, Naqshbandiyya (Khufiyya and Jahriyya) etc. mostly of the Hanafi Madhhab (whereas among the Southeastern communities the Shafi'i Madhhab is more of the norm). Before the "Yihewani" movement, a Chinese Muslim sect inspired by the reform movement in the Middle East, Northern Hui Sufis were very fond of synthesizing Taoist teachings and martial arts practices with Sufi philosophy.

In early modern times, villages in northern Chinese Hui areas still bore labels like "Blue-cap Huihui," "Black-cap Huihui," and "White-cap Huihui," betraying their possible Christian, Judaic and Muslim origins, even though the religious practices among north China Hui by then were by and large Islamic. Hui is also used as a catch-all grouping for Islamic Chinese who are not classified under another ethnic group. In Henan, Guangdong, and Gansu, Jews converted to Islam and were assimilated into the Hui.[55][56][57] A lot of Chinese Jews converted to Islam by the 17th century. The Jews worked in government service and owned big properties in China.[58]

Converted Han

According to legend, a Muhuyindeni person converted an entire village of Han with the surname Zhang to Islam.[59] Another source for the Hui comes from Hui adopting Han children and raising them as Hui.[60] Hui in Gansu with the surname "Tang" 唐 and "Wang" 汪, are descended from Han Chinese who converted to Islam and married Muslim Hui or Dongxiang people, switching their ethnicity and joining the Hui and Dongxiang ethnic groups, both of which are Muslim.

Tangwangchuan and Hanjiaji were notable for being the lone towns with a multi-ethnic community, with both non-Muslims and Muslims.[61]

The Guomindang official Ma Hetian visited Tangwangchuan and met an "elderly local literatus from the Tang clan" while he was on his inspection tour of Gansu and Qinghai.[62]

In Gansu province in the 1800s, a Muslim Hui woman married into the Han Chinese Kong lineage of Dachuan, which was descended from Confucius. The Han Chinese groom and his family were converted to Islam after the marriage by their Muslim relatives.[63] In 1715 in Yunnan province, a few Han Chinese descendants of Confucius surnamed Kong married Hui women and converted to Islam. Archives on this are stored in Xuanwei city.[64]

Tang dynasty

Islam was brought to China during the Tang dynasty by Arab traders, who were primarily concerned with trading and commerce, and less concerned with spreading Islam. They did not try to convert Chinese and only did commerce. It was because of this low profile that the 845 anti Buddhist edict during the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution said absolutely nothing about Islam.[65] It seems that trade occupied the attention of the early Muslim settlers rather than religious propagandism; that while they observed the tenets and practised the rites of their faith in China, they did not undertake any strenuous campaign against either Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, or the State creed, and that they constituted a floating rather than a fixed element of the population, coming and going between China and the West by the oversea or the overland routes.[66][67]

Song dynasty

During the Song Dynasty, Muslims had come to play a major role in foreign trade.[68][69] The office of Director General of Shipping was consistently held by a Muslim during this period.[70] The Song Dynasty hired Muslim mercenaries form Bukhara to fight against Khitan nomads. 5,300 Muslim men from Bukhara were encouraged and invited to move to China in 1070 by the Song emperor Shenzong to help battle the Liao empire in the northeast and repopulate areas ravaged by fighting. The emperor hired these men as mercenaries in his campaign against the Liao empire. Later on these men were settled between the Sung capital of Kaifeng and Yenching (modern day Beijing). The provinces of the north and north-east were settled in 1080 when 10,000 more Muslims were invited into China.[71] They were led by the Amir of Bukhara, Sayyid "So-fei-er" in Chinese. He is called the "Father" of Chinese Islam. Islam was named by the Tang and Song Chinese as Dashi fa ("law of the Arabs").[72] He gave Islam the new name of Huihui Jiao ("the Religion of the Huihui").[73]

Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan Dynasty, which was ruled by Emperors of Mongol origin, deported thousands of Central Asian Muslims, Jews, and Christians into China where they formed the Semu class. Semu people like Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, who served the Yuan dynasty in administrative positions became progenitors of many Hui people. Despite the high position given to Muslims, some policies of the Yuan Emperors severe discriminated against them, forbidding Halal slaughter and other Islamic practices like circumcision, as well as Kosher butchering for Jews, forcing them to eat food the Mongol way.[15] Toward the end, corruption and the persecution became so severe that Muslim Generals joined Han Chinese in rebelling against the Mongols. The Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang had Muslim Generals like Lan Yu who rebelled against the Mongols and defeated them in combat. Some Muslim communities had the name in Chinese which meant "baracks" and also mean "thanks", many Hui Muslims claim it is because that they played an important role in overthrowing the Mongols and it was named in thanks by the Han Chinese for assisting them.[74] The Muslims in the semu class also revolted against the Yuan dynasty in the Ispah Rebellion but the rebellion was crushed and the Muslims were massacred by the Yuan loyalist commander Chen Youding.

Ming Dynasty

The Ming policy towards the Islamic religion was tolerant, while their racial policy towards ethnic minorities was of integration through forced marriage. Muslims were allowed to practice Islam, but if they were members of other ethnic groups they were required by law to intermarry, so Hui had to marry Han since they were different ethnic groups, with the Han often converting to Islam.

The Ming Dynasty employed many Muslims and the Ming Emperor treated Muslims relatively freely. Some Hui people even claimed that the first Ming Emperor Ming Taizu could possibly be a Muslim, but this is rejected by the majority of scholars.[75] Hui troops were also used by the Ming Dynasty to crush the Miao and other aboriginal rebels during the Miao Rebellions, and were also settled in Changde, Hunan, where their descendants still live.[76] Muslims in Ming Dynasty Beijing were given relative freedom by the Chinese, with no restrictions placed on their religious practices or freedom of worship, and being normal citizens in Beijing. In contrast to the freedom granted to Muslims, followers of Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism suffered from restrictions and censure in Beijing.[77]

Integration was mandated through intermarriage by Ming law, ethnic minorities had to marry people of other ethnic groups. The Chinese during the Ming dynasty also tried to force foreigners like the Hui into marrying Chinese women.[78] Marriage between upper class Han Chinese and Hui Muslims was low, since upper class Han Chinese men would both refuse to marry Muslim women, and forbid their daughters from marrying Muslim men, since they did not want to convert due to their upper class status. Only low and mean status Han Chinese men would convert if they wanted to marry a Hui woman. Ming law allowed Han Chinese men and women to not have to marry Hui, and only marry each other, while Hui men and women were required to marry a spouse not of their race.[79][80][81]

The Ming Emperor Hongwu decreed the building of multiple mosques throughout China in many locations. A Nanjing mosque was built by the Xuanzong Emperor.[82]

When the Qing dynasty invaded the Ming dynasty in 1644, Hui Muslim Ming loyalists led by Muslim leaders Milayin, Ding Guodong, and Ma Shouying led a revolt in 1646 against the Qing during the Milayin rebellion in order to drive the Qing out and restore the Ming Prince of Yanchang Zhu Shichuan to the throne as the emperor. The Muslim Ming loyalists were crushed by the Qing with 100,000 of them, including Milayin and Ding Guodong killed.

Qing Dynasty

Muslim revolts

During the mid-nineteenth century, a series of civil wars broke out throughout China by various groups against the Qing dynasty. These include the Taiping Rebellion in Southern China (whose leaders were Evangelical Christians of ethnic Han Chinese Hakka and Zhuang background), the Muslims Rebellion in Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai and Ningxia in Northwestern China and Yunnan, and the Miao people Revolt in Hunan and Guizhou. These revolts were supported by European Powers at the beginning but eventually put down by the Manchu government. The Dungan people were descendants of the Muslim rebels who fled to the Russian Empire after the rebellion were suppressed by the joint force of Hunan Army led by Zuo Zongtang (左宗棠) with support from local Hui elites.

The "Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8" stated that the Dungan and Panthay revolts by the Muslims was set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than the mistaken assumption that it was all due to Islam and religion that the rebellions broke out.[83] The Russian government spent thousands of rubles on an expedition trying to determine the cause of the Dungan revolt, and were unable to figure it out.[84]

The Panthay Rebellion was started when a Muslim from a family of Han Chinese origin which converted to Islam, Du Wenxiu, led some Hui to revolt against the Qing dynasty in the name of driving the Manchu out of China and establishing a unified state of Han and Hui. Du Wenxiu established himself as a Sultan in Yunnan during his revolt. A British officer witnessing the Panthay Rebellion testified that the Muslims did not rebel for religious reasons, and that the Chinese were tolerant of different religions and were unlikely to have caused the revolt by interfering with Islam.[85] In addition, loyalist Muslim forces helped Qing crush the rebel Muslims.[86]

The Dungan revolt (1862–1877) broke out due to a pricing dispute over bamboo poles which a Han merchant was selling to a Hui. After the Dungan revolt broke out, Turkic Andijanis from the Kokand Khanate under Yaqub Beg invaded Xinjiang and fought both Hui rebels and Qing forces. Yaqub Beg's Turkic Kokandi Andijani Uzbek forces declared a Jihad against Chinese Muslim rebels (Dungans) under T'o Ming (Tuo Ming a.k.a. Daud Khalifa) during the Dungan revolt. Yaqub Beg enlisted non Muslim Han Chinese militia under Hsu Hsuehkung in order to fight against the Chinese Muslims in the Battle of Ürümqi (1870). T'o Ming's forces were defeated by Yaqub, who planned to conquer Dzungharia. Yaqub intended to seize all Dungan territory.[87][88][89] Poems were written about the victories of Yaqub Beg's forces over the Chinese Muslims (Dungans) and the Chinese.[90] Hui rebels battled against Turkic Muslims in addition to fighting the Qing. Yakub Beg seized Aksu from Hui forces and forced them north of the Tien Shan mountains, committing massacres upon the Hui (tunganis). Reportedly in 1862 the number of Hui in China proper numbered 30,000,000.[91] During the Dungan revolt, loyalist Hui Muslims helped the Qing crush the rebel Muslims and reconquer Xinjiang from Yaqub Beg,

Despite the population loss, the military power of Hui increased, because some Hui who had defected to the Qing side were promoted and granted high positions in the Imperial Army. One of them, Ma Anliang, became a military warlord in northwest China, and other Generals associated with him grew into the Ma Clique of the Republican era.[92]

During the Panthay Rebellion, the Qing Dynasty did not massacre Muslims who surrendered, in fact, Muslim General Ma Rulong, who surrendered and join the Qing campaign to crush the rebel Muslims, was promoted, and became the most powerful military official in the province.[93][94] Also, the Hui Muslim population of Beijing was unaffected by the Muslim rebels during the Dungan revolt.[95]

Elisabeth Allès wrote that the relationship between Hui Muslim and Han peoples continued normally in the Henan area, with no ramifications or consequences from th Muslim rebellions of other areas. Allès wrote in the document "Notes on some joking relationships between Hui and Han villages in Henan" published by French Centre for Research on Contemporary China that "The major Muslim revolts in the middle of the nineteenth century which involved the Hui in Shaanxi, Gansu and Yunnan, as well as the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, do not seem to have had any direct effect on this region of the central plain."[96]

Another revolt erupted in 1895, which was suppressed by loyalist Muslim troops.

Panthays

Panthays form a group of Chinese Muslims in Burma. Some people refer to Panthays as the oldest group of Chinese Muslims in Burma. However, because of intermixing and cultural diffusion the Panthays are not as distinct a group as there once were.

Dungans

Dungan (simplified Chinese: 东干族; traditional Chinese: 東干族; pinyin: Dōnggānzú; Russian: Дунгане) is a term used in territories of the former Soviet Union and in Xinjiang to refer to Chinese-speaking Muslim people. In the censuses of Russia and the former Soviet Central Asia, the Hui are enumerated separately from Chinese, and are labelled as Dungans. In both China and the former Soviet republics where they reside, however, members of this ethnic group call themselves Lao Huihui or Zhongyuanren, not Dungans. Zhongyuan 中原, literally means "The Central Plain," and is the historical name of Shaanxi and Henan provinces. Most Dungans living in the former Soviet Union are descendants of Hui people from Gansu and Shaanxi.

Islamic sects

The Islamic scholar Ma Tong recorded that among 6,781,500 Hui in China, 58.2% were Gedimu, 21% Yihewani, 10.9% Jahriyya, 7.2% Khuffiya, 1.4% Qadariyya, and 0.7% Kubrawiyya.[5]

Relations with other religions

Some Hui believed that Islam was the true religion through which Confucianism could be practiced, accusing Buddhists and Daoists of being heretics, like most other Confucian scholars. They emphasized that Islam was superior to "barbarian" religions.[97]

Muslim general Ma Bufang allowed polytheists to openly worship and Christian missionaries to station themselves in Qinghai. General Ma and other high-ranking Muslim generals even attended the Kokonuur Lake Ceremony where the God of the Lake was worshipped, and during the ritual, the Chinese national Anthem was sung, all participants bowed to a Portrait of Kuomintang party founder Dr. Sun Zhongshan, and the God of the Lake was also bowed to, and offerings were given to him by the participants, which included the Muslims.[98] Ma Bufang invited Kazakh Muslims to attend the Ceremony honoring the God.[99] Ma Bufang received audiences of Christian missionaries, who sometimes gave him the Gospel.[100][101] His son Ma Jiyuan received a silver cup from Christian missionaries.[102]

The Muslim Ma Zhu wrote "Chinese religions are different from Islam, but the ideas are the same"[103]

During the Panthay Rebellion, the Muslim leader Du Wenxiu said to a Catholic priest- "I have read your religious works and I have found nothing inappropriate. Muslims and Christians are brothers."[104]

Culture

Chinese culture

Hui women once employed foot binding, also practiced among Han women. It was particularly prevalent in Gansu,[105] The Dungan people, descendants of Hui from northwestern China who fled to Central Asia, also practised foot binding until 1948.[106] However, in southern China, in Canton, James Legge enocountered a mosque which had a placard denouncing footbinding, saying Islam did not allow it since it constituted violating the creation of God.[107]

Hui marriages resemble typical Chinese marriages except traditional Chinese rituals are not used.[108]

Unique Islamic practices

A French army Commandant Viscount D'Ollone wrote a report on what he saw among Hui in 1910, during the Qing Dynasty, Sichuanese Hui were slacking in the Islamic practice of alcohol restriction and ritual washing; Friday prayers were not followed. Chinese practices like incense burning at ancestral tablets and honoring Confucius were taken up; however, the one practice which was observed most stringently was the banning of pork consumption.[26]

The Sunni Gedimu and the Yihewani burned incense during worship. This was viewed as Daoist or Buddhist influence.[109] The Hui were also known as the "White capped" HuiHui used incense during worship, while the Salar, also known as "black capped" HuiHui considered this to be a heathen ritual and denounced it.[110]

Some Hui burned incense with ancestral tablets like non Muslim Han Chinese, and honored the philosopher Confucius with ceremonies.[26]

In Yunnan province, during the Qing Dynasty, tablets which wished the Emperor a long life were placed in at the Mosque entrance. No minarets were available and no chanting was done when calling for prayer. The mosques were similar to Buddhist Temples, and incense was burned inside the mosques as well.[111]

The Hui followed Chinese customs and Islamic law, refusing to consume alcohol, opium, and tobacco. Large numbers of Hui enlisted in the military and were praised for their martial skills.[91]

Circumcision in Islam is known as khitan. There is some disagreement among Islamic scholars as to whether it is required, recommended, or forbidden, with a plurality of experts taking the second view. Since circumcision in China does not have the weight of pre-existing traditions as it does in the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere in the Muslim world, circumcision rates among Hui are much lower than among other Muslim groups (where the procedure is in many places nearly always carried out).[112][113][114]

Name

On account of this mixing and long residence in China, the Hui have not retained Central Asian, Persian, or Arabic names, using instead names typical of their Han Chinese neighbors; however, certain names common among the Hui can be understood as Chinese renderings of common Muslim, Arabic, and Central Asian names. For instance, surname "Ma" for "Muhammad".

Hui people usually have a Chinese name and a Muslim name in Arabic, the Chinese name is used primarily. Sometimes Hui do not remember their Muslim names.[115]

When some Hui people adopt foreign names, they do not use their Muslim names. Instead, they, like Han Chinese, prefer to adopt Western names.[116] An example of this is Pai Hsien-yung, a Hui author in America, who adopted the name Kenneth. His father was the Muslim General Bai Chongxi, who had his children adopt western names such as Patsy, Diana, Daniel, Richard, Alfred, Amy, David, Kenneth, Robert and Charlie.

Literature

The Han Kitab was a collection of Islamic and Confucian texts written by various Hui Authors in the 18th century, including Liu Zhi (scholar).

New works were written by Hui intellectuals following education reform by Ma Clique Warlords and Bai Chongxi. Texts were also translated from Arabic.[117]

A new edition of a book by Ma Te-hsin, called Ho-yin Ma Fu-ch'u hsien-sheng i-shu Ta hua tsung kuei Ssu tien yaohui, which was printed in 1865 was reprinted in 1927 by Ma Fuxiang.[118]

The General Ma Fuxiang invested in new editions of Confucian and Islamic texts.[119] He edited Shuofang Daozhi.[120][121][122][123] a gazette, and books such as Meng Cang ZhuangKuang: Hui Bu Xinjiang fu.[124][125]

Language

Hui speak Chinese dialects as their native languages.[citation needed] The Hui of Yunnan (Burmese called them Panthays) were reported to be fluent in Arabic.[126] During the Panthay Rebellion, Arabic replaced Chinese as official language of the rebel kingdom.[127] In Tianmu (天穆村), Tianjin, Hui could speak an old, archaic form of Arabic, when they met Arab Muslims in recent times, it was found out that Old Arabic and Modern Arabic were very different, so Modern Arabic is now being taught to Hui.[128][129]

In 1844 "The Chinese repository, Volume 13" was published, including an account of an Englishman who stayed in the Chinese city of Ningbo. There he visited the local mosque, the Hui running the mosque was from Shandong, and he was a descendant of Muslims from the Arabian city of Medina. He was able to read and speak Arabic with ease, but was totally illiterate in Chinese. He was born in China and spoke Chinese as well.[130]

Marriage

Endogamy is practiced by Hui who are members of different sects, mainly marrying among themselves than with Muslims from other sects.[131]

The Hui Na family in Ningxia is known to practice both parallel and cross cousin marriage.[132] The Najiahu village in Ningxia is named after this family, descended from Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar.[133]

Intermarriage outside ethnic group

Intermarriage involves a Han Chinese woman or a Han Chinese man converting to Islam to marry a Hui. In extremely rare cases, marriage takes place without conversion. In specifically northwest China, intermarriages involve Han women moving in but in some cases it is Han men.[132]

There is a distinction between women marrying out, and men moving into the women's household. Zhao nuxu is a practice where the son in law moves in with the wife's family. Some marriages between Han and Hui are conducted this way, with some Han men moving in with their Hui wife and her family. The husband does not need to convert, but the wife's family follows Islamic customs. No census data collects this type of marriage, the census only reports data where the wife moves in with the groom's family.[134]

In Beijing Oxen street there were 37 Han–Hui couples, two of which were Han with Hui wives, the other 35 were Hui men with Han.[135] Data was collected in different Beijing districts. In Ma Dian 20% of intermarriage were Hui women marrying into Han families, in Tang Fang 11% of intermarriage were Hui women marrying into Han families. 67.3% of intermarriage in Tang Fang were Han women marrying into a Hui family and in Ma Dian 80% of intermarriag were Han women marrying into Hui families.[136]

Li Nu, the son of Li Lu, from a Han Chinese Li family in Quanzhou visited Hormuz in Persia in 1376. He married a Persian or an Arab girl, and brought her back to Quanzhou. He then converted to Islam. Li Nu was the ancestor of the Ming Dynasty reformer Li Chih.[137][138][139]

In Hui discourse, marriage between a Hui woman and a Han man is not allowed unless the Han converts Islam, despite this it occurred several times in the towns of Eastern China.[96] Generally Han of both sexes have to convert to Islam before marrying. This practice helps increase the population of Hui.[140] In 1982 a case occurred where a Han married a Hui woman and moved into her family.[134] A case of switching nationality occurred in 1972 when a Han man married a Hui woman, and is currently considered a Hui after converting to Islam.[132]

In Henan province, a marriage was recorded between Han boy and Hui girl without the Han converting to Islam, during the Ming Dynasty. They had two children who became Muslim. Steles in Han and Hui villages record this story and Hui and Han members of the Lineage celebrate at the ancestral temple together.[141]

In Gansu province in the 1800s, a Muslim Hui woman married into the Han Chinese Kong lineage of Dachuan, which was descended from Confucius. The Han Chinese groom and his family were only converted to Islam after the marriage by their Muslim relatives.[63] In 1715 in Yunnan province, few Han Chinese descendants of Confucius married Hui women and converted to Islam. Archives on this are stored in Xuanwei city.[64]

Research has shown that Hui men marrying Han women display education above average, and Han men who also marry Hui women display education that is above average.[142]

Education

Hui have been interested in modern education and reform. Several Hui, such as Hu Songshan, and the Ma Clique warlords promoted western, modern secular education and reform.

Elite Hui received both Muslim and Confucian education. They studied the Koran and Confucian texts like the Spring and Autumn Annals.[143]

Hui people refused to follow the May Fourth Movement. Instead, they taught both modern, western education such as science, along with traditional Confucian literature and Classical Chinese languages with Islamic education and Arabic in their schools. They merely incorporated the new instead of destroying the old and replacing it.[144]

The Hui Muslim Warlord Ma Bufang built a girl's school for Muslim girls in Linxia which taught modern secular education.[145]

Hui also have female Imams, called Nu Ahong, which they had for centuries. They are the only female Imams in the world, they guide female Muslims in worship and prayer.[146]

History of military service in the Chinese army

Muslims "have often filled the more distinguished military positions.", many Muslims joined the Chinese army.[147] During the Tang Dynasty, 3,000 Chinese soldiers, and 3,000 Muslim soldiers were traded to each other in an agreement.[148]

Muslims served extensively in the Chinese military, as both officials and soldiers. It was said that the Muslim Dongxiang and Salar were given to "eating rations", a reference to military service.[149]

The Hui descend from foreign Muslim mercenaries serving the Tang Dynasty.[150] In 756, over 4,000 Arab mercenaries joined the Chinese against An Lushan. They remained in China, and some of them were ancestors of the Hui people.[60][151][152][153][154]

Hui people have extensively served in the Chinese military. During the Ming Dynasty, Hui Generals and troops loyal to Ming fought against Mongols and Hui loyal to the Yuan Dynasty in the Ming conquest of Yunnan.[155][156] Hui also fought for Ming against aboriginal tribes in southern China during the Miao Rebellions (Ming Dynasty). This resuled in many Hui soldiers of the Ming Dynasty being settled in Yunnan and Hunan provinces in southern China.[76]

During the Qing Dynasty, Hui troops in the Imperial army helped crush Hui rebels during the Dungan revolt, Panthay Rebellion, and Dungan Revolt (1895).

The Qing Dynasty also preferred to use Hui in Xinjiang as police.[157]

Yang Zengxin, the Han Chinese governor of Xinjiang, extensively relied on Hui Generals like Ma Shaowu and Ma Fuxing.

Qing Muslim General Zuo Baogui (左寶貴) (1837–1894), from Shandong province, was martyred in Pingyang in Korea by Japanese cannon fire in 1894 while defending the city. A memorial to him was built.[158]

Hui troops fought against western armies for the first time in the Boxer Rebellion, winning several battles including the Battle of Langfang and Battle of Beicang. These troops were the Kansu Braves led by General Dong Fuxiang.

Military service continued into the Republic of China. The Chinese government appointed Hui General Ma Fuxiang as military governor of Suiyuan. After the Kuomintang party took power, Hui participation in the military reached new levels. Qinghai and Ningxia were created out of Gansu province, and the Kuomintang appointed Hui Generals as military Governors of all three provinces. They became known as the Ma Clique.

Hui Generals and soldiers fought for the Republic of China against Tibet in the Sino-Tibetan War, against Uyghur rebels in the Kumul Rebellion, the Soviet Union in the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang, and against Japan in the Second Sino Japanese War.

Hui forces fought for the Kuomintang (aka the Chinese nationalists) against the Communists in the Chinese Civil War, and against rebels during the Ili Rebellion.

Bai Chongxi, a Hui General, was appointed to the post of Minister of National Defence, the highest Military position in the Republic of China. After the Communist victory, and evacuation of the Kuomintang to Taiwan, Hui people continued to serve in the military.

Ma Bufang, the Muslim General who fought a bloody war against the Tibetans, was made the ambassador of the Republic of China (Taiwan) to Saudi Arabia. His brother, Ma Buqing remained a military General on Taiwan.

Bai Chongxi and Ma Ching-chiang were other Hui who continue to serve in Taiwan as military Generals.

Ma Zhanshan was a Hui guerilla fighter against the Japanese.

A Hui General, Ma Fuxiang, commented on the willingness for Hui people to become martyrs in Battle (see Martyrdom in Islam), saying:

"They have not enjoyed the educational and political privileges of the Han Chinese, and they are in many respects primitive. But they know the meaning of fidelity, and if I say 'do this, although it means death,' they cheerfully obey".[159]

The Chinese Islamic Association issued "A message to all Muslims in China from the Chinese Islamic Association for National Salvation" in Ramadan of 1940 during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

"We have to implement the teaching "the love of the fatherland is an article of faith" by the Prophet Muhammad and to inherit the Hui's glorious history in China. In addition, let us reinforce our unity and participate in the twice more difficult task of supporting a defensive war and promoting religion.... We hope that ahongs and the elite will initiate a movement of prayer during Ramadan and implement group prayer to support our intimate feeling toward Islam. A sincere unity of Muslims should be developed to contribute power towards the expulsion of Japan."

Ahong is the Chinese word for Imam. During the war against Japan, the Imams supported Muslim reisistance in battle, calling for Muslims to participate in the Jihad against Japan, and becoming a shaheed (Islamic term for martyr).[160]

The Japanese planned to invade Ningxia from Suiyuan in 1939 and create a Hui puppet state. The next year in 1940, the Japanese were defeated militarily by the Kuomintang Muslim General Ma Hongbin, who caused the plan to collapse. Ma Hongbin's Hui Muslim troops launched further attacks against Japan in the Battle of West Suiyuan.[161]

The PLA used Hui soldiers, who formally had served under Ma Bufang to crush the Tibetan revolt in Amdo during the 1959 Tibetan uprising.[162]

Politics

The Majority of the Hui Muslim Ma Clique Generals were Kuomintang party members, and encouraged Chinese nationalism in their provinces. Ma Qi, Ma Lin (warlord), and Ma Bufang were Hui Generals who served as Military Governors of Qinghai, Ma Hongbin served as military Governor of Gansu, and Ma Hongkui served as military governor of Ningxia. All of them were Kuomintang party members. General Ma Fuxiang, a Hui Kuomintang member, was promoted to Governor of Anhui and became chairman of Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs. Ma Bufang, Ma Fuxiang, and Bai Chongxi were all members of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, which ruled China in a Single-party state. Bai Chongxi, as a Kuomintang member, helped build the Taipei Grand Mosque on Taiwan. Many members of the Hui Ma Clique were also Kuomintang members.

Hui put Kuomintang Blue Sky with a White Sun party symbols on their Halal restaurants and shops. A Christian missionary in 1935 took a picture of a Muslim meat restaurant in Hankow which had Arabic and Chinese lettering indicating that it was Halal (fit for Muslim consumption), and it had two Kuomintang party symbols on it.[163][164]

Hui in Taiwan

A community of Hui people exists in Taiwan, see Islam in Taiwan.

Chinese identity

Some prominent Hui, such as Imam Ma Chao-yen of the Taipei Grand Mosque, refer to themselves and other Hui people as Chinese in English, and consider themselves to practice Chinese, Confucian Culture.[165]

The term Chinese Muslim is sometimes used to refer to Hui people. This is based mainly in the fact that their native language is a Chinese dialect, in contrast to Turkic speaking Salars and other Muslims. During the Qing Dynasty, "Chinese Muslim" (Han Hui) was the term sometimes used to refer to Hui people, which differentiated them from non-Chinese speaking Muslims. In contrast, the Uyghurs were called "Chan Tou Hui" ("Turban Headed Muslim"), and the Turkic Salars called "Sala Hui" (Salar Muslim). While the Turkic speakers often referred the Hui as "Dungan".[28][166] John Stuart Thomson, who traveled in China called them "Mohammedan Chinese".[167] Because the Qing Dynasty grouped Muslims by language, the Chinese-speaking Hui had to wear the queue, while most Turkic Hui do not, except for their leaders.[168] They have also been called "Chinese Mussulmans", when Europeans wanted to distinguish them from Han Chinese.[169]

The Qing authorities considered both Han and Hui to be Chinese, and in Xinjiang Both Hui and Han were classified as merchants regardless of profession.[170] Laws were passed segregating the different races, in theory, keeping Turkic Muslims apart from Hui and Han, however, the law was not followed.[171] Hui and Han households were built closer together in the same area while Turkic Muslims would live farther away from the town.[172]

Before the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, when the revolutionaries faced the ideological dilemma on how to unify the country while at the same time acknowledging ethnic minorities, Hui people were noted as Chinese Muslims, separate from Uyghurs.[173] The Jahriyya Sufi leader Ma Yuanzhang said in response to accusations that Muslims were disloyal to China: "Our lives, livelihoods, and graves are in China. . . . We have been good citizens among the Five Nationalities!".[174] The Muslim General Ma Fuxiang encouraged Confucian style assimilation for all Muslims into Chinese culture, and even set up an assimilationist group for this purpose.[175] Imams such as Hu Songshan encouraged Chinese nationalism in their mosques, and the Yihewani was led by many nationalist Imams.[176][177]

For some Uyghurs, there is barely any difference between Hui and Han. A Uyghur social scientist, Dilshat, regarded Hui as the same people as Han, deliberately calling Hui people Han and dismissing the Hui as having only a few hundred years of history.[178]

The Kuomintang party and, Chiang Kai-shek, the Kuomintang party leader, considered all the minority peoples of China, including the Hui, as descendants of Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor and semi mythical founder of the Chinese nation, and belonging to the Chinese Nation Zhonghua Minzu and he introduced this into Kuomintang ideology, which was propagated into the educational system of the Republic of China.[179][180][181]

Hui as nationality or as religion

Some Hui clans who identify as Hui and are recognized as such by the Chinese government are Hui because of their ancestry only, and do not practice Islam as their religion. They had Muslim ancestors but they do not practice Islam anymore.[182] Throughout history, when their ancestors first abandoned Islam as a religion, their identity has been fluid, claiming their "identity" based on what was convenient for the time.[183] The modern definition of Hui by the Chinese government is as a nationality, and not a religion.[184] These Hui are led to identify as Hui out of interest in their ancestry or because of affirmative action benefits which they will get from the Chinese government. These Hui are concentrated on the southeast coast of China, especially Fujian province.[185] In 1913, a westerner noted that many people in Fujian province had Arab ancestry, but were no longer Muslim.[186]

Some well known Hui clans around Quanzhou in Fujian, such as the Ding and the Guo families, are examples of these Hui who identify as Muslim by nationality but do not practice Islam. Due to more people of these clans identifying as Hui the population of Hui has grown.[187][188][189] All these clans needed were only evidence of ancestry from Arab, or Persian, or other Muslim ancestors to be recognized as Hui, and they do not need to practice Islam.[190] It was the Communist party and its policies which encouraged the definition of Hui as a nationality or ethnicity.[191] It is taboo to offer pork to ancestors in the Ding clan family. However, the living Ding family members themselves consume pork.[192][193] The Chinese Government's Historic Artifacts Bureau preserved tombs of Arabs and Persians whom Hui are descended from around Quanzhou.[194] Many of these Hui worship village gods and do not have Islam as their religion, some are Buddhists, Daoists, followers of Chinese Folk Religions, secularlists, and Christians.[195] Many clans with thousands of members in numerous villages across Fujian recorded their genealogies and had Muslim ancestry.[196] These Hui clans originating in Fujian have strong sense of unity among their members, despite being scattered across a wide area in Asia, such as Fujian, Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, and Philippines.[197][198]

On Taiwan, there are also descendants of Hui who came with Koxinga who no longer observe Islam, the Taiwan branch of the Guo (romanized as Kuo in Taiwan) family is not Muslim, but still does not offer pork at ancestral shrines. The Chinese Muslim Association counts these people as Muslims.[199] Also on Taiwan, one branch of this Ding (Ting) family descended from Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar resides in Taisi Township in Yunlin County. They trace their descent through him via the Quanzhou Ding family of Fujian. Even as they were pretending to be Han Chinese in Fujian, they still practiced Islam when they originally came to Taiwan 200 years ago, building a mosque, but eventually became Buddhist or Daoist. The Mosque is now the Ding families Daoist temple.[200]

An attempt was made by the Chinese Islamic Society to reconvert the Hui of Fujian back to Islam in 1983, sending 4 Ningxia Imams to Fujian.[201] This futile endeavour ended in 1986, when the final Ningxia Imam remaining decided to go back and leave Fujian. A similar endeavour in Taiwan also failed to meet its goals.[202]

Before 1982, it was possible for a Han to change ethnicity to the Hui nationality just by converting, after 1982 converted Han were no longer counted as Hui, instead, they are now known as "Muslim Han". Hui people consider other Hui who do not observe Islamic practices to still be Hui, they consider it impossible to ever lose their Hui nationality, even if a Hui becomes atheist the other Muslim Hui still consider them to be Muslim, albeit a bad one.[203]

Ethnic tensions

Promotion and wealth were few of the motives among Chinese Muslim military officers for anti-foreignism.[204]

The Dungan Revolt and Panthay revolts by the Hui were also set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than the mistaken assumption that it was all due to Islam that the rebellions broke out.[83] During the Dungan revolt fighting broke out between Uyghurs and Hui.[90]

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 20,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, the Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslims, the Kazakhs, until there were 135 of them left.[205][206]

The Hui people have had a long presence in Qinghai and Gansu, or what Tibetans call Amdo, although Tibetans have historically dominated the local politics. The situation was reversed in 1931 when the Hui general Ma Bufang inherited the governorship of Qinghai, stacking his government with Hui and Salar and excluding Tibetans. In his power base in Qinghai's northeastern Haidong Prefecture, Ma compelled many Tibetans to convert to Islam and acculturate into the Hui community. When Hui started migrating into Lhasa in the 1990s, racist rumors circulated among Tibetans in Lhasa about the Hui, such as that they were cannibals or ate children.[207] On February 2003, Tibetans rioted against Hui, destroying Hui-owned shops and restaurants.[208] Local Tibetan Buddhist religious leaders lead a regional boycott movement that encouraged Tibetans to boycott Hui-owned shops, spreading the racist myth that Hui put the ashes of cremated imams in the cooking water they use to serve Tibetans food, in order to convert Tibetans to Islam.[207]

Occasionally tensions result in scuffles between Hui communities and the native Tibetans and some Muslims have stopped wearing the traditional white caps that identify their religion, and many women now wear a hairnet instead of a scarf in order to better assimilate into the community. The Hui community usually support the Chinese government in anti Tibetan separatism.[209] In addition, Chinese speaking Hui have problems with Tibetan Hui (the Tibetan speaking Kache minority of Muslims).[210]

Tensions with Uyghurs arose because Qing and Republican Chinese authorities used Hui troops and officials to dominate the Uyghurs and crush Uyghur revolts.[211] Xinjiang's Hui population increased by over 520 percent between 1940 and 1982, an average annual growth of 4.4 percent, while the Uyghur population only grew at 1.7 percent. This dramatic increase in Hui population led inevitably to significant tensions between the Hui and Uyghur Muslim populations. Some old Uyghurs in Kashgar remember that the Hui army at the Battle of Kashgar (1934) massacred 2,000 to 8,000 Uyghurs, which causes tension as more Hui moved into Kashgar from other parts of China.[212] Some Hui criticize Uyghur separatism, and generally do not want to get involved in conflict in other countries over Islam for fear of being perceived as radical.[213] Hui and Uyghur separate from each other, praying and attending different mosques.[214]

Surnames

Hui people commonly believe that their surnames originated as "Sinified" forms of their foreign Muslim ancestors some time during the Yuan or Ming eras.[215] These are some common surnames used by the Hui ethnic group:[132][216][217][218]

- Ma for Muhammad

- Mu for Muhammad[219]

- Han for Muhammad

- Ha for Hasan

- Hu for Hussein

- Sai for Said

- Sha for Shah

- Zheng for Shams

- Guo (Koay) for Kamaruddin

- Cai (Chuah) for Osman

A legend in Ningxia states that four Hui surnames common in the region - Na, Su, La, and Ding - originate with the descendants of one Nasruddin, a son of Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, who "divided" the ancestor's name (Nasulading, in Chinese) among themselves.[220]

Prominent Hui people

- Bai Chongxi (白崇禧), Minister of Defense of the Republic of China

- Bai Shouyi (白壽彝), prominent Chinese historian and ethnologist

- Pai Tzu-li, general of the 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army)

- Dong Fuxiang (董福祥), Qing Dynasty General

- Hui Liangyu (回良玉), a Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China

- Hu Songshan (虎嵩山), Imam and Chinese nationalist

- Jia Xiaochen (賈曉晨), Hong Kong singer

- Lan Yu, Ming Dynasty general who ended the Mongol dream to reconquer China.

- Li Zhi (李贄), famous Confucian philosopher in Ming Dynasty, would perhaps be considered a Hui if he lived today because of some his ancestors being Persian Muslims.

- Liu Bin Di was a Hui KMT officer who died while fighting against Uyghur rebels in the Ili Rebellion.[221] Liu was killed by Uyghur rebels backed by the Soviet Union.

- Cecilia Liu (劉詩詩), actress

- Liu Hui, Chairwoman of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region.

- Ma Dexin (马德新), Islamic scholar in Yunnan

- Ma Anliang (馬安良) Qing Dynasty General

- Ma Zhanshan (馬占山), guerilla warrior against the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War

- Ma Chengxiang, (馬呈祥), warlord in China during the Republic of China era, son of Ma Buqing

- Ma Ching-chiang, Republic of China Army Lt. General

- Ma Dunjing (1906-1972), (馬惇靖) Republic of China Lieutenant-General

- Ma Dunjing (1910-2003), (馬敦靜) Republic of China Lieutenant-General

- Ma Fulu (馬福綠) Qing Dynasty Army Officer

- Ma Fushou (馬福壽) Qing Dynasty Army Officer

- Ma Fuxiang (馬福祥) Qing Dynasty General and a warlord in China during the Republic of China era

- Ma Fuyuan (馬福元) Republic of China general

- Ma Guoliang Qing Dynasty Army Officer

- Ma Haiyan (馬海晏) Qing Dynasty General

- Ma Hongbin (馬鴻賓) Republic of China general

- Ma Hongkui (馬鴻逵) Republic of China general

- Ma Hushan (馬虎山) Republic of China general

- Ma Jiyuan (馬繼援) Republic of China general

- Ma Ju-lung Republic of China general

- Ma Julung, Qing Dynasty general

- Ma Zhancang (馬占倉) Republic of China general

- Ma Lin (warlord) (馬麟) Qing Dynasty and Republic of China general

- Ma Linyi Gansu Minister of Education

- Ma Qi (馬麒), Qing Dynasty and Republic of China general

- Ma Qixi, founder of the Xidaotang

- Ma Qianling (馬千齡) Qing Dynasty General

- Ma Zhanao (馬占鰲) Qing Dynasty General

- Ma Zhanhai, Republic of China general

- Ma Hualong (马化龙), one of the leaders of the Muslim Rebellion of 1862-77.

- Ma Sanli, one of the most respected Chinese stand-up comedians.

- Ma Shaowu (馬紹武), Daotai of Kashgar

- Ma Shenglin (馬聖鱗), Panthay Rebellion rebel and great uncle of Ma Shaowu

- Ma Sheng-kuei, a General of the 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army)

- Ma Yuanzhang, (馬元章) a Jahriyya Sufi leader, uncle of Ma Shaowu

- Ma Xiao, Republic of China general in Liu Wenhui's army

- Ma Xinyi, (馬新貽), official and a military general of the late Qing Dynasty in China.

- Tang Kesan, representative of the Kuomintang in Xikang

- Kasim Tuet, entrepreneur and Islamic educationalist in Hong Kong

- Su Chin-shou, a General of the 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army)

- Wang Zi-Ping, martial artist who participated in the Boxer Rebellion

- Zuo Baogui (左寶貴) (1837–1894), Qing Muslim General from Shandong province, was martyred in Pingyang in Korea by Japanese cannon fire in 1894 while defending the city. A memorial to him was built.[158]

- Zhang Chengzhi (張承志), contemporary author and alleged creator of the term "Red Guards"

- Zhang Linpeng (张琳芃), Chinese international footballer

- Zheng He (鄭和), a fleet admiral and probably the most famous Muslim in Ming Dynasty.

- Zhang Hongtu (张宏图) an artist known for his paintings and sculptures.

Related group names

- Dungan (in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan)

- Panthay (in Burma)

- Utsul (in Hainan Island; speakers of a Malayo-Polynesian language, but officially classified by the Chinese government as Hui)

See also

| Islam in China |

|---|

|

|

History History Tang Dynasty • Song Dynasty |

|

Major figures |

|

Culture |

- Chin Haw - Chinese Thai, one-third of whom are Hui

- Hui pan-nationalism

- Hui people in Beijing

- Islam in China

- Hui Minorities' War

- Panthay Rebellion

Further reading

- Chuah, Osman (April 2004). "Muslims in China: the social and economic situation of the Hui Chinese". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 24 (1): 155–162. doi:10.1080/1360200042000212133.

- Hillman, Ben (2004). "The Rise of the Community in Rural China: Village Politics, Cultural Identity and Religious Revival in a Hui Hamlet". The China Journal 51 (51): 53–73. doi:10.2307/3182146.

- Islam in China, Hui and Uyghurs: between modernization and sinicization, the study of the Hui and Uyghurs of China, Jean A. Berlie, White Lotus Press editor, Bangkok, Thailand, published in 2004. ISBN 974-480-062-3, ISBN 978-974-480-062-6.

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). Traders of the Golden Triangle. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B006GMID5K

Footnotes

-

This article incorporates text from Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1, a publication from 1863 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1, a publication from 1863 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The Moslem World, Volume 10, by Christian Literature Society for India, Hartford Seminary Foundation, a publication from 1920 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Moslem World, Volume 10, by Christian Literature Society for India, Hartford Seminary Foundation, a publication from 1920 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55: as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine, by Willem van Ruysbroeck, Giovanni (da Pian del Carpine, Archbishop of Antivari), a publication from 1900 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55: as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine, by Willem van Ruysbroeck, Giovanni (da Pian del Carpine, Archbishop of Antivari), a publication from 1900 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from China revolutionized, by John Stuart Thomson, a publication from 1913 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from China revolutionized, by John Stuart Thomson, a publication from 1913 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from Accounts and papers of the House of Commons, by Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons, a publication from 1871 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Accounts and papers of the House of Commons, by Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons, a publication from 1871 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The River of golden sand, condensed by E.C. Baber, ed. by H. Yule, by William John Gill, a publication from 1883 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The River of golden sand, condensed by E.C. Baber, ed. by H. Yule, by William John Gill, a publication from 1883 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from Burma past and present, by Albert Fytche, a publication from 1878 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Burma past and present, by Albert Fytche, a publication from 1878 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The religions of China: Confucianism and Tâoism described and compared with Christianity, by James Legge, a publication from 1880 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The religions of China: Confucianism and Tâoism described and compared with Christianity, by James Legge, a publication from 1880 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The history of China, Volume 2, by Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh Boulger, a publication from 1898 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The history of China, Volume 2, by Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh Boulger, a publication from 1898 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The River of golden sand, condensed by E.C. Baber, ed. by H. Yule, by William John Gill, a publication from 1883 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The River of golden sand, condensed by E.C. Baber, ed. by H. Yule, by William John Gill, a publication from 1883 now in the public domain in the United States. -

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ↑ [2011 census]

- ↑ Lipman (1997), p. xxiii, or Gladney (1996), pp. 18-20. Besides the Hui people, nine other officially recognized ethnic groups of PRC are considered predominantly Muslim. Those nine groups are defined mainly on linguistic grounds: namely, six groups speaking Turkic languages ( Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Salars, Uzbeks, and Tatars), two Mongolic-speaking groups (Dongxiang and Bonan), and one Iranian-speaking group (Tajiks).

- ↑ Gladney (1996), p. 20.

- ↑ Of course, many members of some other Chinese ethnic minorities don't speak their ethnic group's traditional language anymore, and practically no Manchu people speak the Manchu language natively anymore; but even the Manchu language is well attested historically. Meanwhile the ancestors of today's Hui people are thought to have been predominantly native Chinese speakers of foreign Arab and Persian ancestry since no later than the mid- or early Ming Dynasty (Lipman (1997), p. 50.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Esposito, John (2000-04-06). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 443–444, 462. ISBN 0-19-510799-3.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), p. 13. Quote: "In China, pork has been the basic meat protein for centuries and regarded by Chairman Mao as 'a national treasure'"

- ↑ Wei 2002, p. 181

- ↑ Different matrilineal contributions to genetic... [Mol Biol Evol. 2004] - PubMed - NCBI

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15317881?dopt=Abstract

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gladney (1996), pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), pp. 33-34. The Bai-speaking Hui typically claim descent of Hui refugees who fled to Bai areas after the defeat of the Panthay Rebellion, and have assimilated to the Bai culture since

- ↑ http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/China%201.pdf

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Dru C. Gladney (1996), p.18; or Lipman (1997), pp. xxiii-xxiv.

- ↑ Gladney (2004), p. 161; he refers to Leslie (1986), pp. 195-196.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims". The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. p. 12. Retrieved 30 November 2010..

- ↑ Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1. s.n. 1863. p. 18. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ↑ Israeli, Raphael (2002). Islam in China. United States of America: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0375-X.

- ↑ Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims". The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. Retrieved 30 November 2010..

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Hong Kong University Press. p. 33. ISBN 962-209-468-6.

- ↑ Dillon (1999), p. 13.

- ↑ Dillon (1999), p. 15.

- ↑ Trigault, Nicolas S. J. "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583-1610". English translation by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (New York: Random House, Inc. 1953). This is an English translation of the Latin work, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas based on Matteo Ricci's journals completed by Nicolas Trigault. Pp. 106-107. There is also full Latin text available on Google Books.

- ↑ Trigault (trans.) (1953), p. 112. In Samuel Purchas's translation (1625) (Vol. XII, p. 466): "All these Sects the Chinois call, Hoei, the Jewes distinguished by their refusing to eate the sinew or leg; the Saracens, Swines flesh; the Christians, by refusing to feed on round-hoofed beasts, Asses, Horses, Mules, which all both Chinois, Saracens and Jewes doe there feed on." It's not entirely clear what Ricci means by saying that Hui also applied to Christians, as he does not report finding any actual local Christians.

- ↑ Trigault (trans.) (1953), p. 375.

- ↑ James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. T. & T. Clark. p. 892. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), p. 18; Lipman (1997), p. xxiii

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Garnaut, Anthony. "From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals". Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University). p. 95. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ Stéphane A. Dudoignon, Hisao Komatsu, Yasushi Kosugi; Hisao Komatsu, Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ China Heritage Newsletter.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), pp. 18-19, or Gladney (2004), pp. 161-162.

- ↑ On the continuing use of Huijiao in Taiwan, see Gladney (1996), pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), pp. 12-13.

- ↑ James Prinsep, "Memoir on Chinese Tartary and Khoten". The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, No. 48, December 1835. P. 655.On Google Books. Prinsep's article is also available in "The Chinese Repository", 1843, p. 234 On Google Books. A modern (2003) reprint is available, ISBN 1-4021-5631-6.

- ↑ Owen Lattimore, Inner Asian Frontiers of China. Page 183 in the 1951 edition.

- ↑ James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. T. & T. Clark. p. 892. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Gladney (1996), pp. 33, 399.

- ↑ Richard V. Weekes (1984). Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey, Volume 1. Greenwood Press. p. 334. ISBN 0-313-23392-6. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ James Stuart Olson, Nicholas Charles Pappas (1994). An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 202. ISBN 0-313-27497-5. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ James A. Millward (1998). Beyond the pass: economy, ethnicity, and empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864. Stanford University Press. p. 215. ISBN 0-8047-2933-6. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Laura Newby (2005). The Empire and the Khanate: a political history of Qing relations with Khoqand c. 1760-1860. BRILL. p. 148. ISBN 90-04-14550-8. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Ralph Kauz (2010-05-20). Ralph Kauz, ed. Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 3-447-06103-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Australian National University. Dept. of Far Eastern History (1986). Papers on Far Eastern history, Issues 33-36. Australian National University, Dept. of Far Eastern History. p. 90. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Gabriel Ronay (1978-01-01). The Tartar Khan's Englishman (illustrated ed.). Cassell. p. 111. ISBN 0-304-30054-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Willem van Ruysbroeck, Giovanni (da Pian del Carpine, Archbishop of Antivari) (1900). William Woodville Rockhill, ed. The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55: as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Printed for the Hakluyt Society. p. 13. Retrieved 2010-06-28.