Huangshan

| Huangshan 黄山 | |

|---|---|

Panoramic view of the Huangshan landscape | |

| Elevation | 1,864 m (6,115 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 1,734 m (5,689 ft)[1] |

| Listing | Ultra |

| Location | |

Huangshan 黄山 | |

| Location | Anhui, China |

| Coordinates | 30°07′30″N 118°10′00″E / 30.12500°N 118.16667°ECoordinates: 30°07′30″N 118°10′00″E / 30.12500°N 118.16667°E[1] |

| Mount Huangshan | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| Type | Cultural & Natural |

| Criteria | ii, vii, x |

| Reference | 547 |

| UNESCO region | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1990 (14th Session) |

Huangshan (simplified Chinese: 黄山; traditional Chinese: 黃山; pinyin: Huángshān; literally "Yellow Mountain"),[2] is a mountain range in southern Anhui province in eastern China. The range is composed of material that was uplifted from an ancient sea during the Mesozoic era, 100 million years ago. The mountains themselves were carved by glaciers during the Quaternary. Vegetation on the range is thickest below 1,100 meters (3,600 ft), with trees growing up to the treeline at 1,800 meters (5,900 ft).

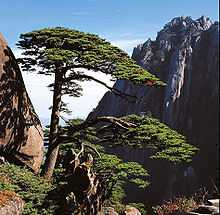

The area is well known for its scenery, sunsets, peculiarly shaped granite peaks, Huangshan Pine trees, and views of the clouds from above. Huangshan is a frequent subject of traditional Chinese paintings and literature, as well as modern photography. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and one of China's major tourist destinations.

Physical description

Huangshan is known for its sunrises,[3] pine trees,[4] "strangely jutting granite peaks",[5] and views of clouds touching the mountainsides for more than 200 days out of the year.[2][4][5][6]

The Huangshan mountain range has many peaks, some more than 1,000 meters (3,250 feet) high.[7] The three tallest and best-known peaks are Lotus Peak (Lian Hua Feng, 1,864 m), Bright Summit Peak (Guang Ming Ding, 1,840 m), and Celestial Peak (Tian Du Feng, literally Capital of Heaven Peak, 1,829 m).[2][5] The World Heritage Site covers a core area of 154 square kilometres and a buffer zone of 142 square kilometres.[8] The mountains were formed in the Mesozoic, about 100 million years ago, when an ancient sea disappeared due to uplift.[9] Later, in the Quaternary Period, the landscape was shaped by the influence of glaciers.[9]

The vegetation of the area varies with elevation. Mesic forests cover the landscape below 1,100 meters. Deciduous forest stretches from 1,100 meters up to the tree line at 1,800 meters. Above that point, the vegetation consists of alpine grasslands. The area has diverse flora, where one-third of China's bryophyte families and more than half of its fern families are represented. The Huangshan pine (Pinus hwangshanensis) is named after Huangshan and is considered an example of vigor because the trees thrive by growing straight out of the rocks.[9] Many of the area's pine trees are more than a hundred years old and have been given their own names (such as the Ying Ke Pine, or Welcoming-Guests Pine, which is thought to be over 1500 years old).[5] The pines vary greatly in shape and size, with the most crooked of the trees being considered the most attractive.[6] Furthermore, Huangshan's moist climate facilitates the growing of tea leaves,[10] and the mountain has been called "one of China's premier green tea-growing mountains.[11] Mao feng cha ("Fur Peak Tea"), a well-known local variety of green tea,[12] takes its name from the downy tips of tea leaves found in the Huangshan area.[13]

The mountaintops often offer views of the clouds from above, known as the Sea of Clouds (Chinese: 云海; pinyin: yúnhǎi)[10] or "Huangshan Sea"[6] because of the cloud's resemblance to an ocean, and many vistas are known by names such as "North Sea" or "South Sea."[6] One writer remarked on the view of the clouds from Huangshan as follows:To enjoy the magnificence of a mountain, you have to look upwards in most cases. To enjoy Mount Huangshan, however, you've got to look downward.[6]

The area is also host to notable light effects, such as the renowned sunrises. Watching the sunrise is considered a "mandatory" part of visiting the area.[3] A phenomenon known as Buddha's Light (Chinese: 佛光; pinyin: fóguāng)[14] is also well-known and, on average, Buddha's Light only appears a couple of times per month.[15] In addition, Huangshan has multiple hot springs, most of them located at the foot of the Purple Cloud Peak. The water stays at 42 °C all year[16] and has a high concentration of carbonates, and is said to help prevent skin, joint, and nerve illness.[9]

History

Huangshan was formed approximately 100 million years ago and gained its unique rock formations in the Quaternary Glaciation.[9]

During the Qin Dynasty, Huangshan was known as Yishan (Mount Yi). In 747 AD, its name was changed to Huangshan (Mount Huang) by imperial decree;[17] the name is commonly thought to have been coined in honor of Huang Di (the Yellow Emperor), a legendary Chinese emperor and the mythological ancestor of the Han Chinese.[18] One legend states that Huangshan was the location from which the Yellow Emperor ascended to Heaven.[5] Another legend states that the Yellow Emperor "cultivated moral character and refined Pills of Immortality in the mountains, and in so doing gave the mountains his name.[9] The first use of this name "Huangshan" is often attributed to Chinese poet Li Bai.[18] Huangshan was fairly inaccessible and little-known in ancient times, but its change of name in 747 AD seems to have brought the area more attention; from then on, the area was visited frequently and many temples were built there.[17]

Huangshan is known for its stone steps,[5] carved into the side of the mountain, of which there may be more than 60,000 throughout the area.[3][19][20] The date at which work on the steps began is unknown, but they have been said to be over 1,500 years old.[19]

Over the years, many scenic spots and physical features on the mountain have been named;[6] many of the names have narratives behind them. For example, one legend tells of a man who did not believe the tales of Huangshan's beauty and went to the mountains to see for himself; he was almost immediately convinced. One of the peaks he supposedly visited was named Shixin (始信), roughly meaning "start to believe."[6]

In 1982, Huangshan was declared a "site of scenic beauty and historic interest" by the State Council of the People's Republic of China.[17] It was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1990 for its scenery and for its role as a habitat for rare and threatened species.[4]

In 2002, Huangshan was named the "sister mountain" of Jungfrau in the Swiss Alps.[5]

Artistic and scientific inspirations

Much of Huangshan's reputation derives from its significance in Chinese art and literature.[21] In addition to inspiring poets such as Li Bai,[3][8] Huangshan and the scenery therein has been the frequent subject of poetry and artwork, especially Chinese ink painting[17] and, more recently, photography.[2] Overall, from the Tang Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty, over 20,000 poems were written about Huangshan, and a school of painting named after it.[5][6] The mountains have also appeared in modern works. James Cameron, director of the 2009 film Avatar, cited Huangshan as one of his influences in designing the fictional world of that film.[22]

The area has also been a location for scientific research because of its diversity of flora and wildlife. In the early part of the 20th century, the geology and vegetation of Huangshan were the subject of multiple studies by both Chinese and foreign scientists.[17] The mountain is still a subject of research. For example, in the late 20th century a team of researchers used the area for a field study of Tibetan Macaques, a local species of monkey.[23]

Tourism

Having at least 140 sections open to visitors,[4] Huangshan is a major tourist destination in China.[2][3] In 2007, for instance, over 15 million tourists visited the mountain.[24] The foot of the mountains is linked by rail and by air to Shanghai,[2] and is also accessible from cities such as Hangzhou and Wuhu.[25] As of 1990, there were over 50 kilometers of footpaths providing access to scenic areas for visitors and staffers of the facilities.[17] Today there are also cable cars that tourists can use to ride directly from the base to one of the summits.[2] Throughout the area there are hotels and guest houses that accommodate overnight visitors,[2][17] many of whom hike up the mountains, spend the night at one of the peaks to view the sunrise, and then descend by a different route the next day.[3] The area is classified as a AAAAA scenic area by the China National Tourism Administration.[26]

The hotels, restaurants, and other facilities at the top of the mountain are serviced and kept stocked by porters who carry resources up the mountain on foot, hanging their cargo from long poles balanced over their shoulders or backs.[27]

Climate

Huangshan's elevation moderates summer temperatures, creating an oceanic (Cfb) climate. Winters can be cold and snowy at times, while summers are cool.

| Climate data for Huangshan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1 (34) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

11 (52) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

8 (46) |

4 (39) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−1 (30) |

3 (37) |

8 (46) |

12 (54) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

17 (63) |

14 (57) |

9 (48) |

4 (39) |

0 (32) |

8.1 (46.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6 (21) |

−4 (25) |

−1 (30) |

5 (41) |

9 (48) |

13 (55) |

16 (61) |

15 (59) |

11 (52) |

7 (45) |

1 (34) |

−3 (27) |

5.3 (41.5) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 79 (3.11) |

112 (4.41) |

183 (7.2) |

233 (9.17) |

273 (10.75) |

459 (18.07) |

335 (13.19) |

305 (12.01) |

180 (7.09) |

112 (4.41) |

83 (3.27) |

51 (2.01) |

2,405 (94.69) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 181 |

| Source: CMA | |||||||||||||

Image gallery

-

Carved steps at Huangshan

-

Pine trees on Huangshan mountain peak

-

Clouds in Huangshan

-

Scenery in Huangshan

-

A rock formation in Huangshan

-

Carved steps to Celestial Peak (天都顶)

-

Huangshan rock face

-

A Chinese ink painting depicting Huangshan

-

Huangshan pines

-

Huangshan at dusk, near Guangming Peak (光明顶)

-

Hotels for tourists atop peaks of Huangshan

-

A sunrise at Guangming Peak

-

Sunrise at the North Sea

-

Huangshan with trees and clouds

-

Mount Huangshan

-

Tourist steps built on the cliffs of Huangshan

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Lianhua Feng - Lotus Peak, HP Huang Shan" on Peaklist.org - Central and Eastern China, Taiwan and Korea. This data is specific to the high point of the range only. Retrieved 2011-10-5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Bernstein, pp. 125–127.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Butterfield, Fox (1981-02-08). "China's Majestic Huang Shan". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Mount Huangshan". China.org.cn. 1990. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Cao, pp. 114–127.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Guo, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ "Huangshan Mountain". Huangshan Tour. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Mount Huangshan - UNESCO World Heritage Center". UNESCO. 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Huangshan Mountains, p. 12.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Heiss, p. 124

- ↑ Heiss, p. 113

- ↑ Heiss, p. 52

- ↑ "Yellow Mountain Maofeng Tea". Cultural China. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ China News Service (21 December 2007). ""Buddha's Light" in Huangshan Mountain". China.org.cn. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ↑ Raitisoja, Geni (4 October 2006). "Huangshan: "No. 1 Mountain Under Heaven"". radio86. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ↑ "Welcome to Huang Shan, Mount Huang". Famous Taoism and Buddhism Sanctuaries in China. Wudang Taoist Internal Alchemy. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 "Mount Huangshan Scenic Beauty and Historic Interest Site". Protected Areas and World Heritage. United Nations Environment Programme. October 1990. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Huang Shan". ChinaTravel.net. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "The Mystic World of Shanshui: Huangshan" (.wmv). UNESCO Culture Center. UNESCO. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ McGraw, David (2003). "Magic Precincts". University of Hawaii. Retrieved 6 December 2008. p. 52.

- ↑ McGraw, p. 109

- ↑ Renjie, Mao (24 December 2009). "Stunning Avatar". Global Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ Ogawa, p.9.

- ↑ "China's Huangshan to restrict vehicles during Olympics". Xinhua. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ "Hefei, Anhui Province". Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ↑ "AAAAA Scenic Areas". China National Tourism Administration. 16 November 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Heiss, p. 132

References

- Bernstein, Ken (1999). China pocket guide. Revised by JD Brown; edited by Richard Wallis. Berlitz Publishing Company. ISBN 2-8315-7049-2.

- Cao Nanyan (2003). China: World Heritage Sites. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press. ISBN 0-7607-8685-2.

- Guo Changjian; Song Jianzhi (2003). World Heritage Sites in China. 五洲传播出版社 (Wuzhou Publishing House). ISBN 7-5085-0226-4.

- Heiss, Mary Lou; Robert J. Heiss (2007). The Story of Tea. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 1-58008-745-0.

- Huangshan Mountains. China Travel and Tourism Press. 1998. ISBN 7-5032-1520-8.

- Ogawa, Hideshi; Akie Yanagi (2006). Wily Monkeys: Social Intelligence of Tibetan Macaques. Trans Pacific Press. ISBN 1-920901-97-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Huangshan overview by the Huangshan Management Committee

- Huangshan Mountain Travel Guide by Huangshan China International Travel Service

- 始信峰 - 百度百科

| |||||||||||