Hoverfly

| Syrphidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sixteen different species of hoverfly | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Suborder: | Brachycera |

| Section: | Aschiza |

| Superfamily: | Syrphoidea |

| Family: | Syrphidae Latreille, 1802 |

| Subfamilies | |

Hoverflies, sometimes called flower flies or syrphid flies, make up the insect family Syrphidae. As their common name suggests, they are often seen hovering or nectaring at flowers; the adults of many species feed mainly on nectar and pollen, while the larvae (maggots) eat a wide range of foods. In some species, the larvae are saprotrophs, eating decaying plant and animal matter in the soil or in ponds and streams. In other species, the larvae are insectivores and prey on aphids, thrips, and other plant-sucking insects.

Aphids alone cause tens of millions of dollars of damage to crops worldwide every year; because of this, aphidophagous hoverflies are being recognized as important natural enemies of pests, and potential agents for use in biological control. Some adult syrphid flies are important pollinators.

About 6,000 species in 200 genera have been described. Hoverflies are common throughout the world and can be found on all continents except Antarctica. Hoverflies are harmless to most other animals despite their mimicry of more dangerous wasps and bees, which serves to ward off predators.

Description

The size of hoverflies varies, depending on the species.[1] Some, like members of the genus Baccha, are small, elongate and slender, while others, like members of Criorhina are large, hairy, and yellow and black. As members of Diptera, all hoverflies have a single functional pair of wings (the hindwings are reduced to balancing organs).[2] They are brightly colored, with spots, stripes, and bands of yellow or brown covering their bodies.[2] Due to this coloring, they are often mistaken for wasps or bees; they exhibit Batesian mimicry. Despite this, hoverflies are harmless.[1]

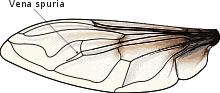

With a few exceptions (e.g.[3]), hoverflies are distinguished from other flies by a spurious vein, located parallel to the fourth longitudinal wing vein.[1] Adults feed mainly on nectar and pollen.[2] They also hover around flowers, lending to their common name.[1]

Reproduction and life cycle

Unlike adults, the maggots of hoverflies feed on a variety of foods; some are saprotrophs, eating decaying plant or animal matter, while others are insectivores, eating aphids, thrips, and other plant-sucking insects.[1] This is beneficial to gardens, as aphids destroy crops, and hoverfly maggots are often used in biological control. Certain species, such as Lampetia equestris or Eumerus tuberculatus, are responsible for pollination.

An example of a well-known hoverfly maggot is the rat-tailed maggot, of the drone fly, Eristalis tenax. It has a breathing siphon at its rear end, giving it its name.[1] The species lives in stagnant water, such as sewage and lagoons.[4] The maggots also have a commercial use, and are sometimes sold for ice fishing.[5]

On occasion, Hoverfly larvae have been known to cause accidental myiasis in humans. This occurs when the larva are accidentally ingested on food or from other sources. Myiasis causes discomfort, pain, or itching,[4][6] however, Hoverflies do not normally prey upon humans and cases of myiasis from Hoverflies is very rare.

Distribution and habitat

Hoverflies are a cosmopolitan family found in most biomes, except deserts, tundra at extremely high latitudes, and Antarctica.[7][8] Certain species are more common in certain areas than others; for example, the American hoverfly, Eupeodes americanus, is common in the Nearctic ecozone, and the common hoverfly, Melangyna viridiceps, is common in the Australasia ecozone. About 6,000 species and 200 genera are in the family.[9]

Larvae of hoverflies are often found in stagnant water. Adults are often found near plants, their principal food source being nectar and pollen.[2] Some species are found in more unusual locations; for example, members of the genus Volucella can be found in bumblebee nests, while members of Microdon are myrmecophiles, found in ant or termite nests.[1] Others can be found in decomposing vegetation.

Pollination

.jpg)

Hoverflies are important pollinators of flowering plants in a variety of ecosystems worldwide.[10] Syrphid flies are frequent flower visitors to a wide range of wild plants as well as agricultural crops and are often considered to be the second most important group of pollinators after wild bees. However, there has been relatively little research into fly pollinators compared with bee species.[10] It is thought that bees are able to carry a greater volume of pollen on their bodies, but flies may be able to compensate for this by making a greater number of flower visits.

Like many pollinator groups, syrphid flies range from species that take a generalist approach to foraging by visiting a wide range of plant species to those which are specialists and are more selective in the plants they visit. Although hoverflies are often considered to be mainly non-selective pollinators some hoverflies species are highly selective and carry pollen from one plant species.[11] It is thought that Cheilosia albitarsis will only visit Ranunculus repens.

Specific flower preferences differ between species but syrphid fly species have repeatedly been shown to prefer white and yellow coloured flowers.[12] Non-visual visual flower cues such as olfactory cues also help the flies to find flowers, especially those which are not yellow.[13] Many syrphid fly species have short, unspecialized mouth parts and tend to feed on flowers that are more open as the nectar and pollen can be easily accessed.[14]

There are also a number of fascinating interactions between orchids and hoverflies. The orchid species Epipactis veratrifolia mimics alarm pheromones of aphids in order to attract hoverflies for pollination.[15] Another plant, the slipper orchid in southwest China, also achieves pollination by deceit by exploiting the innate yellow color preference of syrphide.[16]

Case study - New Zealand

There are more than 40 species of syrphid flies in New Zealand.[17] These flies are found in a variety of habitats including agricultural fields and alpine zones. Two hoverfly species in Switzerland are being investigated as potential biological control agents of hawkweeds in New Zealand.[18]

Native hoverfly species Melanostoma fasciatum and Melangyna novaezelandiae, are common on agricultural fields in New Zealand.[19] Coriander and tansy leaf are known to be particularly attractive to many species of adult hoverflies which feed on large quantities of pollen of these plants.[20] In organic paddocks hoverflies were found to feed on an average of three and a maximum of six different pollen types. M. fasciatum has a short proboscis which restricts it to obtaining nectar from disk flowers.[21]

Syrphid flies are also common visitors to flowers in alpine zones in New Zealand. Native flies (Allograpta and Platycheirus) in alpine zones show preferences for flower species based on their colour in alpine zones; syrphid flies consistently choose yellow flowers over white regardless of species.[22] However, syrphid flies are not as effective pollinators of alpine herb species as native solitary bees.[23]

Systematics

See Genera of Syrphidae.

Relationship with people

Many species of hoverfly larvae prey upon pest insects, including aphids and the leafhoppers, which spread some diseases such as curly top. Therefore, they are seen in biocontrol as a natural means of reducing the levels of pests.

Gardeners, therefore, will sometimes use companion plants to attract hoverflies. Those reputed to do so include alyssum, Iberis umbellata, statice, buckwheat, chamomile, parsley, and yarrow.

Identification guides

- Stubbs, A.E. and Falk, S.J. (2002) British Hoverflies An Illustrated Identification Guide. Pub. 1983 with 469 pages, 12 col plates, b/w illus.British Entomological and Natural History Society [ISBN 1-899935-05-3]. 276 species are described with extensive keys to aid identification. 190 species are displayed on the colour plates. 2nd edition, pub. 2002, includes new British species and name changes. Also includes European species which are likely to be found in Britain. There are additional black & white plates illustrating the male genitalia of the difficult genera Cheilosia and Sphaerophoria.

- Vockeroth, J.R. A revision of the genera of the Syrphini (Diptera: Syrphidae) Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada, no. 62:1-176. Keys subfamilies, tribes and genera on a world basis and under regions.

- van Veen, M.P. |(2004) "Hoverflies of Northwest Europe, Identification Keys to the Syrphidae". KNNV Publishing, Utrecht. [ISBN 9050111998]

Regional Lists

- List of hoverfly species of Great Britain

- List of New Zealand Flower Flies

- List of the Flower Flies of North America

See also

- Episyrphus balteatus - marmalade fly (worldwide distribution)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Hover fly". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Hoverfly". Hutchinson Encyclopedia. Helicon Publishing. 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ↑ Reemer, Menno (2008). "Surimyia, a new genus of Microdontinae, with notes on Paragodon Thompson, 1969 (Diptera, Syrphidae)" (PDF). Zoologische Mededelingen 82: 177–188.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Aguilera A, Cid A, Regueiro BJ, Prieto JM, Noya M (September 1999). "Intestinal myiasis caused by Eristalis tenax". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 37 (9): 3082. PMC 85471. PMID 10475752.

- ↑ Dictionary of Ichthyology; Brian W. Coad and Don E. McAllister at ww.briancoad.com

- ↑ Whish-Wilson PB (2000). "A possible case of intestinal myiasis due to Eristalis tenax". The Medical Journal of Australia 173 (11–12): 652. PMID 11379520.

- ↑ Barkemeyer, Werner. "Syrphidae (hoverflies)". Biodiversity Explorer. South Africa: Iziko Museum. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ↑ Thompson, F. Christian (August 19, 1999). "Flower Flies". The Diptera Site. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ↑ Philip J. Scholl, E. Paul Catts & Gary R. Mullen (2009). "Myiasis (Muscoidea, Oestroidea)". In Gary Mullen, Gary Richard Mullen & Lance Durden. Medical and Veterinary Entomology (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 309–338. ISBN 978-0-12-372500-4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Larson, B.M.H; Kevan, P.G. & Inouye, D. W. (2001). "Flies and flowers: taxonomic diversity of anthophiles and pollinators.". Canadian Entomologist 133: 439–465.

- ↑ Haslett, J.R. (1989). "Interpreting patterns of resource utilization: randomness and selectivity in pollen feeding by adult hoverflies.". Oecologia 78: 433–442.

- ↑ Sajjad, Asif; Saeed, Shafqat (2010). "Floral host plant range of syrphid flies (Syrphidae: Diptera) under natural conditions in southern punjab, Pakistan.". Pakistan Journal of Biology 42 (2): 1187–1200.

- ↑ Primante, Clara; Dotterl, Stefan (2010). "A syrphid fly uses olfactory cues to find a non-yellow flower.". Journal of Chemical Ecology 36: 1207–1210.

- ↑ Campbell, Alistair, J.; Biesmeijer, J. C., Varma, V., & Wakers, F. L. (2012). "Realising multiple ecosystem services based on the response of three beneficial insect groups to floral traits and trait diversity.". Basic and applied ecology 13: 363–370.

- ↑ Stokl, Johannes; Brodmann, Dafni, Ayasse & Hansson (2011). "Smells like aphids: orchid flowers mimic aphid alarm pheromones to attract hoverflies for pollination.". Proc. R. Soc. B 278: 1216–1222.

- ↑ Shi, J.; Luo, Y.B., Ran, J.C., Liu, Z.J., & Zhou, Q. (2009). "Pollination by deceit in Paphiopedilum barbigerum (Orchidaceae): a staminode exploits innate colour preferences of hoverflies (Syrphidae).". Plant Biology 11: 17–28.

- ↑ "Diptera: Syrphidae". Landcare Research. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ Grosskopf, Gitta (2005). "Biology and life history of Cheliosia urbana (Meigen) and Cheilosia psilophthalma (Becker), two sympatric hoverflies approved for the biological control of hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.) in New Zealand.". Biological Control 35: 142–154.

- ↑ Morris, Michael, C. (2000). "Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) "companion plants" can attract hover flies, and may reduce infestation in cabbages.". New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science 28: 213–217.

- ↑ Hickman, Janice, M.; Lovei, G. L., Wratten, S. D. (1995). "Pollen feeding by adults of the hoverfly Melanostoma fasciatum (Diptera: Syrphidae).". New Zealand Journal of Zoology 22: 387–392.

- ↑ Holloway, Beverley, A. (1976). "Pollen-feeding in hover-flies (Diptera:Syrphidae).". New Zealand Journal of Ecology 3 (4): 339–350.

- ↑ Campbell, Diane; Bischoff, M., Lord, J. M., & Robertson, A. W. (2010). "Flower color influences insect visitation in alpine New Zealand.". Ecology 91 (9): 2638–2649.

- ↑ Bischoff, Mascha; Campbell, D. R., Lord, J. M. & Robertson, A. W. (2013). "The relative importance of solitary bees and syrphid flies as pollinators of two outcrossing plant species in the New Zealand alpine.". Austral Ecology 38: 169–176.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syrphidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Syrphidae |

- Hoverfly - index to scholarly articles

- Syrphidae in Italian

- A web-site about Dutch hoverflies

- Hoverfly Recording Scheme - UK Dipterists Forum

- Syrphidae species in Europe and Africa, with photos, range maps, checklists and literature

- Family Syrphidae at EOL Image Gallery

- Northwest Europe Hoverflies - archived at The Wayback Machine

- Photographs of World Hoverflies from Japan, in English

- Diptera.info Picture Gallery

- "A hover fly, Allograpta obliqua". Featured Creatures. University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Species lists

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||