House of Lusignan

| House of Lusignan | |

|---|---|

Lusignan Coat of Arms | |

| Country |

|

| Titles |

|

| Founded | 885 |

| Founder | Hugh I of Lusignan |

| Final ruler | King James III of Cyprus |

| Dissolution | 1473 |

The Lusignan family originated in Poitou near Lusignan in western France in the early 10th century. By the end of the 11th century, they had risen to become the most prominent petty lords in the region from their castle at Lusignan. In the late 12th century, through marriage and inheritance, a cadet branch of the family came to control the Kingdoms of Jerusalem and of Cyprus, while in the early 13th century, the main branch succeeded in the Counties of La Marche and Angoulême. As Crusader princes in the Latin East, they soon had connections with the Hethumid rulers of the Kingdom of Cilicia, which they inherited through marriage in the mid-14th century. The Armenian and Cypriot branches of the family eventually merged and the dynasty died out after the Ottoman conquest of their Asian kingdoms.

Origins

The Château de Lusignan, near Poitiers, was the principal seat of the Lusignans; it was destroyed during the Wars of Religion, and only its foundations remain in Lusignan. According to legend the earliest castle was built by the folklore water-spirit Melusine. The lords of the castle at Lusignan were counts of La Marche, over which they frequently fought with the counts of Angoulême. Count Hugh le Brun ("Hugh the Swarthy"), like most of the lords of Poitou, backed Arthur of Brittany as the better heir to Richard Lionheart when John Lackland acceded to the throne of England in 1199. Eleanor of Aquitaine traded English claims for their support of John. To secure his position in La Marche, the widowed Hugh arranged a betrothal with the daughter of his next rival of Angoulême, no more than a child; John however married her himself, in August 1200, and deprived Hugh of La Marche and his brother of Eu in Normandy. The aggrieved Lusignans turned to their liege lord, Philip Augustus, King of France. Philip demanded John's presence—a tactical impossibility—and declared John a contumacious vassal. As the Lusignan allies managed to detain both Arthur and Eleanor, John surprised their unprepared forces at the castle of Mirebeau, in July 1202, and took Hugh prisoner with 200 more of Poitou's fighting men. King John's savage treatment of the captives turned the tide against himself, and his French barons began to desert him in droves. Thus the Lusignans' diplomatic rebellion led directly to the loss of half of England's French territory, which was soon incorporated into France by Philip Augustus (The other "half", Aquitaine, was the possession of Eleanor, who was still alive).

Lords of Lusignan

Counts of La Marche

Hugh VI inherited by collateral succession the County of La Marche (1091) as descendant of Almodis.

Counts of La Marche and Angoulême

Hugh IX's son, Hugh X, married Isabelle of Angoulême, thus securing Angoulême (1220).

- Hugh X (died 1249)

- Hugh XI (died 1250)

- Hugh XII (died 1270)

- Hugh XIII (died 1303)

- Guy (died 1308)

- Yolande (died 1314)

- Yolande sold the fiefs of Lusignan, La Marche, Angoulême, and Fougères to Philip IV of France in 1308. They became a part of the French royal demesne and a common appanage of the crown.

Crusader kings

The Lusignans were among the French nobles who made great careers in the Crusades. An ancestor of the later Lusignan dynasty in the Holy Land, Hugh VI of Lusignan, was killed in the east during the Crusade of 1101. Another Hugh arrived in the 1160s and was captured in a battle with Nur ad-Din Zangi. In the 1170s, Amalric arrived in Jerusalem, having been expelled by Richard Lionheart (at that point, acting Duke of Aquitaine) from his realm, which included the family lands of Lusignan near Poitiers. Amalric married Eschiva, the daughter of Baldwin of Ibelin, and entered court circles. He had also obtained the patronage of Agnes of Courtenay, the divorced mother of King Baldwin IV, who held the county of Jaffa and Ascalon and was married to Reginald of Sidon. He was appointed Agnes's constable in Jaffa, and later constable of the kingdom. Hostile rumours alleged he was Agnes's lover, but this is questionable. It is likely that his promotions were aimed at weaning him away from the political orbit of the Ibelin family, who were associated with Raymond III of Tripoli, Amalric I's cousin and the former bailli or regent. Amalric's younger brother, Guy, arrived at some date before Easter 1180. When he arrived is quite unknown, unless we accept the statement of Ernoul that he arrived at this precise juncture on Amalric's advice. Many modern historians believe that Guy was already well established in Jerusalem by 1180, but there is no contemporary evidence to support this belief. What is certain is that Amalric of Lusignan's success facilitated Guy's social and political advancement.

Older accounts (derived from William of Tyre and Ernoul) claim that Agnes was concerned that her political rivals, headed by Raymond of Tripoli, were determined to exercise more control by forcing Agnes' daughter, the princess Sibylla, to marry someone of their choosing, and that Agnes foiled these plans by advising her son to have Sibylla married to Guy. However, it seems that the King, who was less malleable than earlier historians have portrayed, was considering the international implications: it was vital for Sibylla to marry someone who could rally external help to the kingdom, not someone from the local nobility. With the new King of France, Philip II, a minor, the chief hope of external aid was Baldwin's first cousin Henry II, who owed the Pope a penitential pilgrimage on account of the Thomas Becket affair. Guy was a vassal of Richard of Poitou and Henry II, and as a formerly rebellious vassal, it was in their interests to keep him overseas.

Guy and Sibylla were hastily married at Eastertide 1180, apparently preventing a coup by Raymond's faction to marry her to Amalric of Lusignan's father-in-law, Baldwin of Ibelin. By his marriage Guy also became count of Jaffa and Ascalon and bailli of Jerusalem. He and Sibylla had two daughters, Alice and Maria. Sibylla already had one child, a son from her first marriage to William of Montferrat.

An ambitious man, Guy convinced Baldwin IV to name him regent in early 1182. However, he and Raynald of Châtillon made provocations against Saladin during a two-year period of truce. But it was his military hesitance at the siege of Kerak which disillusioned the king with him. Throughout late 1183 and 1184 Baldwin IV tried to have his sister's marriage to Guy annulled, showing that Baldwin still held his sister with some favour. Baldwin IV had wanted a loyal brother-in-law, and was frustrated in Guy's hard-headedness and disobedience. Sibylla was held up in Ascalon, though perhaps not against her will. Unsuccessful in prying his sister and close heir away from Guy, the king and the Haute Cour altered the succession, placing Baldwin V, Sibylla's son from her first marriage, in precedence over Sibylla, and decreeing a process to choose the monarch afterwards between Sibylla and Isabella (whom Baldwin and the Haute Cour thus recognized as at least equally entitled to succession as Sibylla), though she was not herself excluded from the succession. Guy kept a low profile from 1183 until his wife became queen in 1186.

Guy's term as king is generally seen as a disaster; he was defeated by Saladin at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, and was imprisoned in Damascus as Saladin reconquered almost the entire kingdom. Upon his release, his claim to the kingship was ignored, and when Sibylla died at the Siege of Acre in 1191, he no longer had any legal right to it. Richard, now king of England and a leader of the Third Crusade, supported Guy's claim, but in the aftermath of the crusade Conrad of Montferrat had the support of the majority of nobles. Instead, Richard sold Guy the island of Cyprus, which he had conquered on his way to Acre. Guy thereby became the first Latin lord of Cyprus. Amalric succeeded Guy in Cyprus, and also became King of Jerusalem in 1198. Amalric was responsible for establishing the Roman Catholic Church on Cyprus.

The male line of the Lusignans in the Levant died out in 1267 with Hugh II of Cyprus, Amalric's great-grandson (the male line continued in France until 1308).

First house of Lusignan: kings of Jerusalem and Cyprus

- Guy, King of Jerusalem from 1186 to 1192 then of Cyprus until 1194

- Amalric II, King of Cyprus from 1194 to 1205 and of Jerusalem from 1198

- Hugh I (1205–1218), King of Cyprus only, as his descendants

- Henry I (1218–1253)

- Hugh II (1253–1267)

Second House of Lusignan

At that point, Hugh of Antioch, whose maternal grandfather had been Hugh I of Cyprus, a male heir of the original Lusignan dynasty, took the name Lusignan, thus founding the second House of Lusignan, and managed to succeed his deceased cousin as King of Cyprus. These "new" Lusignans, who were also descendants of Robert Guiscard, remained in control of Cyprus until 1489; in Jerusalem (or, more accurately, Acre), they ruled from 1268 until the fall of the city in 1291, after an interlude (1228–1268) during which the Hohenstaufen dynasty officially held the kingdom. After 1291 the Lusignans continued to claim the lost Jerusalem, and occasionally attempted to organize crusades to recapture territory on the mainland.

In 1300, the Lusignans, led by Amalric, Prince of Tyre entered into combined military operations with the Mongols under Ghazan to retake the Holy Land:

"That year [1300], a message came to Cyprus from Ghazan, king of the Tatars, saying that he would come during the winter, and that he wished that the Frank join him in Armenia (...) Amalric of Lusignan, Constable of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, arrived in November (...) and brought with him 300 knights, and as many or more of the Templars and Hospitallers (...) In February a great admiral of the Tatars, named Cotlesser, came to Antioch with 60,000 horsemen, and requested the visit of the king of Armenia, who came with Guy of Ibelin, Count of Jaffa, and John, lord of Giblet. And when they arrived, Cotelesse told them that Ghazan had met great trouble of wind and cold on his way. Cotlesse raided the land from Haleppo to La Chemelle, and returned to his country without doing more".—Le Templier de Tyre, Chap 620–622[2]

Second house of Lusignan: kings of Jerusalem and Cyprus

- Hugh III (1267–1284)

- John I (1284–1285)

- Henry II (1285–1324)

- Amalric (1306–1310), usurper

- Hugh IV (1324–1359)

- Peter I (1359–1369)

- Peter II (1369–1382)

- James I (1382–1398)

- Janus (1398–1432)

- John II (1432–1458)

- Charlotte (1458–1464)

- James II (1464–1473)

- James III (1473–1474)

Kings of Armenian Cilicia

In the 13th century the Lusignans also intermarried with the royal families of the Principality of Antioch and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. The Hethoumids ruled Cilicia until the murder of Leon IV in 1341, when his cousin Guy de Lusignan (who took the name of Constantine II of Armenia) was elected king. The Lusignan dynasty was of French origin, and already had a foothold in the area, the Island of Cyprus. There had always been close relations between the Lusignans of Cyprus and the Armenians. However, when the pro-Latin Lusignans took power, they tried to impose Catholicism and the European way of life. The Armenian leadership largely accepted this, but the peasantry opposed the changes. Eventually, this led way to civil strife.[3]

In the late 14th century, Cilicia was invaded by the Mameluks. The fall of Sis in April, 1375 put an end to the kingdom; its last King, Leon V, was granted safe passage and died in exile in Paris in 1393 after calling in vain for another Crusade. The title was claimed by his cousin, James I of Cyprus, uniting it with the titles of Cyprus and Jerusalem.[3] The last fully independent Armenian entity of the Middle Ages was thus decimated after three centuries of sovereignty.

Lusignan kings of Cilicia (Armenia)

- Constantine II (1342–1344)

- Constantine III (1344–1362)

- Constantine IV (1362–1373)

- Leo V (1374–1393)

The Armenian kingdom was inherited by the Cypriot Lusignans in 1393. After the loss of Cyprus in 1489 the Levantine line continued in Constantinople and from the 19th century in Saint-Petersburg. The last reigning Prince in Constantinople was Christodule de Lusignan who was a direct descendant of kings Janus, Jacques I and Hugo IV. After his arrival in Russia in 1827, his son Louis de Lusignan was recognised as "Royal Prince of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia” by the Russian Emperor Nicholas I. This line of descent was defended in the French civil tribunals in 1880's by Prince Michel de Lusignan, son of Louis and grandson of Chistodule, who resided in St.Petersbourg. As head of the royal house, Prince Michel was also recognized as the Grand Master of the Royal Order of the Sword of Cyprus (L'Ordre Royal de L'Epee de Chypre). The current reigning prince of this line is Prince Constantine de Lusignan.[4],[5]

Besides the Cypriot branch, through the acts of the Count of Poitiers, Alphonse de Poitiers, by the 18th century the domains of Lusignans were divided among a number of other branches :

- Lusignan-Lezay

- Lusignan-Vouvant

- Lusignan-Cognac

- Lusignan-Jarnac (the Counts d'Eu)

- The principal branch retains Lusignan and the County of La Marche

Two of the Lusignan domains in France were erected into feudal Marquisates in 1618 and 1722 by Kings Louis XIII and Louis XV respectively. One has been held by the Franco-Irish Lusignan-O'Mara family since 21 June 1900. ‘[6]’

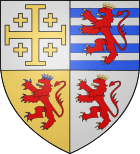

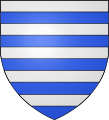

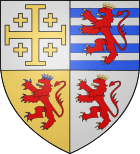

Lusignan Coat of Arms

-

Earlier arms of the Lusignans as French noble house.

-

Arms of Hugh X.

-

Arms of Guy de Lusignan

-

Coat of arms of the Lusignan Kings of Jerusalem and Cyprus. The use of the Lion was a gift from Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade

-

.svg.png)

Arms of the Prince of Galilee

-

Arms of Marie of Lusignan, Queen of Aragon.

-

Coat of Arms of the Lusignan Kings of Armenia from 1393 onward.

In Popular Culture

- Kingdom of Heaven (film) centers on the Battle of Hattin and capture of Jerusalem, with Marton Csokas playing Guy of Lusignan.

- La reine de Chypre 1841 opera by Fromental Halévy.

References

- ↑ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". Cartelfr.louvre.fr. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- ↑ "Medieval Sourcebook: Guillame de Tyr (William of Tyre)" (in (French)). Fordham.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 (Armenian) Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Badmoutioun Hayots, Volume II. Athens, Greece: Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Oussoumnagan Khorhourti. pp. 29–56.

4.Chanoine Pascal, Histoire de la Maison royale de Lusignan, Paris, Léon Vanier, 1896.

5. Histoire Des Prices De Lusignan, Anciens Rois de Jerusalem, de la Petite Armenie et de Chypre, St. Petersbourg, Soikine, 1903.

6. Dictionnaire des Titres et des terres titrées en France sous l'ancien régime», Eric Thiou, Éditions Mémoire et Documents, Versailles, 2003

Further reading

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lusignan". Encyclopædia Britannica 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 130–131 Endnotes:

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lusignan". Encyclopædia Britannica 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 130–131 Endnotes:

- J. M. J. L. de Mas-Latrie, Histoire de l'île de Chypre sous les princes de la maison de Lusignan (Paris, 1852-1853)

- W. Stubbs, Lectures on Medieval and Modern History (3rd ed., Oxford, 1900)